In his essay on screen depictions of Israel, Rick Richman notes an apparent paradox. Despite the central role Jews played in building Hollywood, he suggests there aren’t many good examples. Partly to avoid accusations of undue influence or special pleading, Jewish producers, directors, and writers have been reluctant to tell explicitly Jewish stories. And the films that have been made tend to coopt Israel into a moral narrative that is ostensibly universal, yet also very American. Rather than the state of the Jewish people in the biblical promised land, Israel is used as a metaphor for unavoidable human struggles between tradition and modernity, justice and power, belonging and freedom.

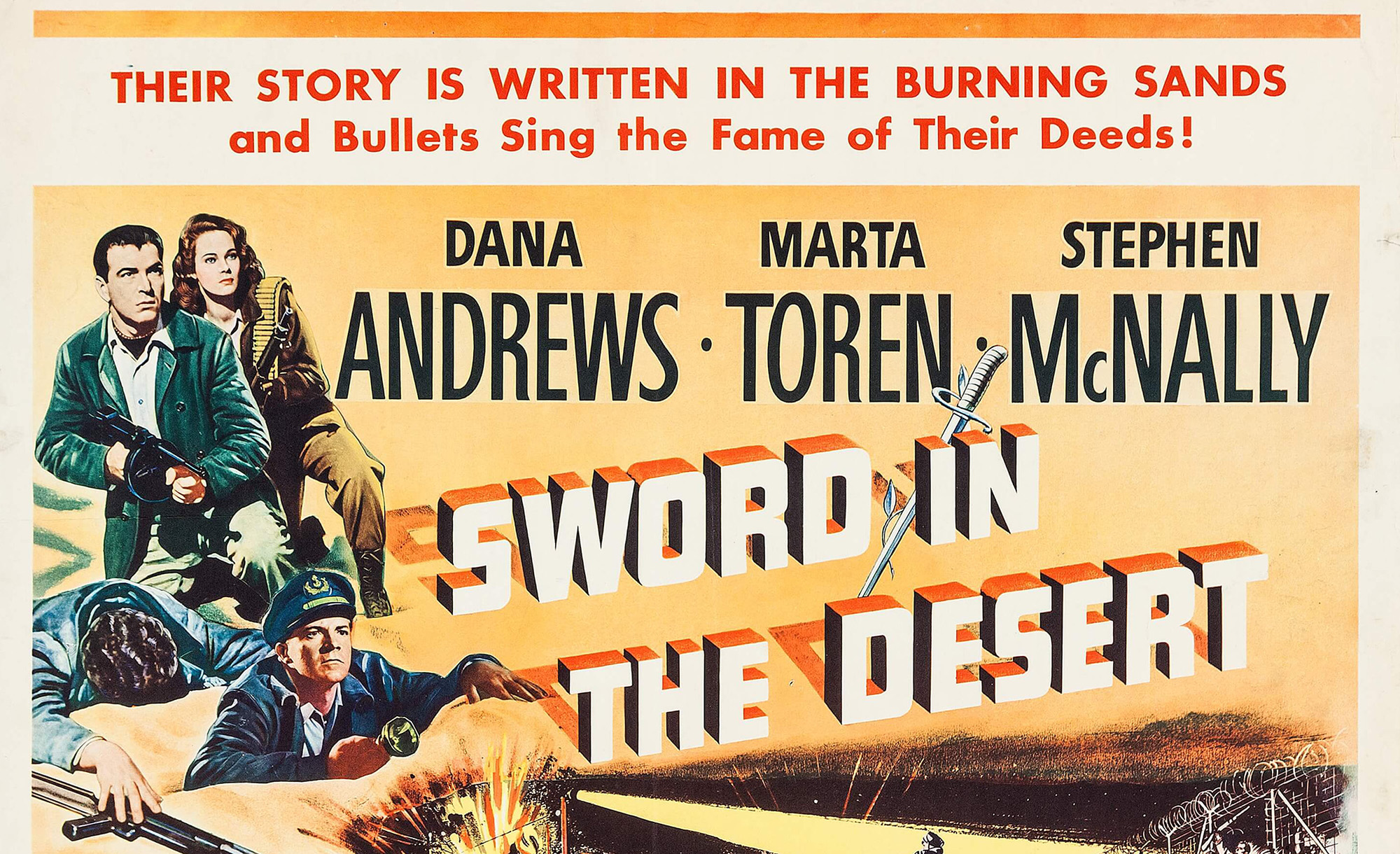

As a matter of cinema history, I am not sure how accurate this account is. In fact, Hollywood produced more and earlier films about Zionism and Israel than Richman notes. In 1949, Universal Pictures released Sword in the Desert. Set just a few years earlier, in the last days of the British Mandate for Palestine, the plot, which vaguely resembles Casablanca, revolves around a cynical American who is drawn into the military struggle for Jewish sovereignty. The film is also notable because it includes the first major screen appearance by the actor Jeff Chandler (born Ira Grossel), who plays the Zionist leader Kurta. Chandler would go on to be an outspoken advocate for Israel and produced the 1976 film The Story of David, which was shot partly in Israel and widely released in theaters outside the U.S., where it was broadcast on network television.

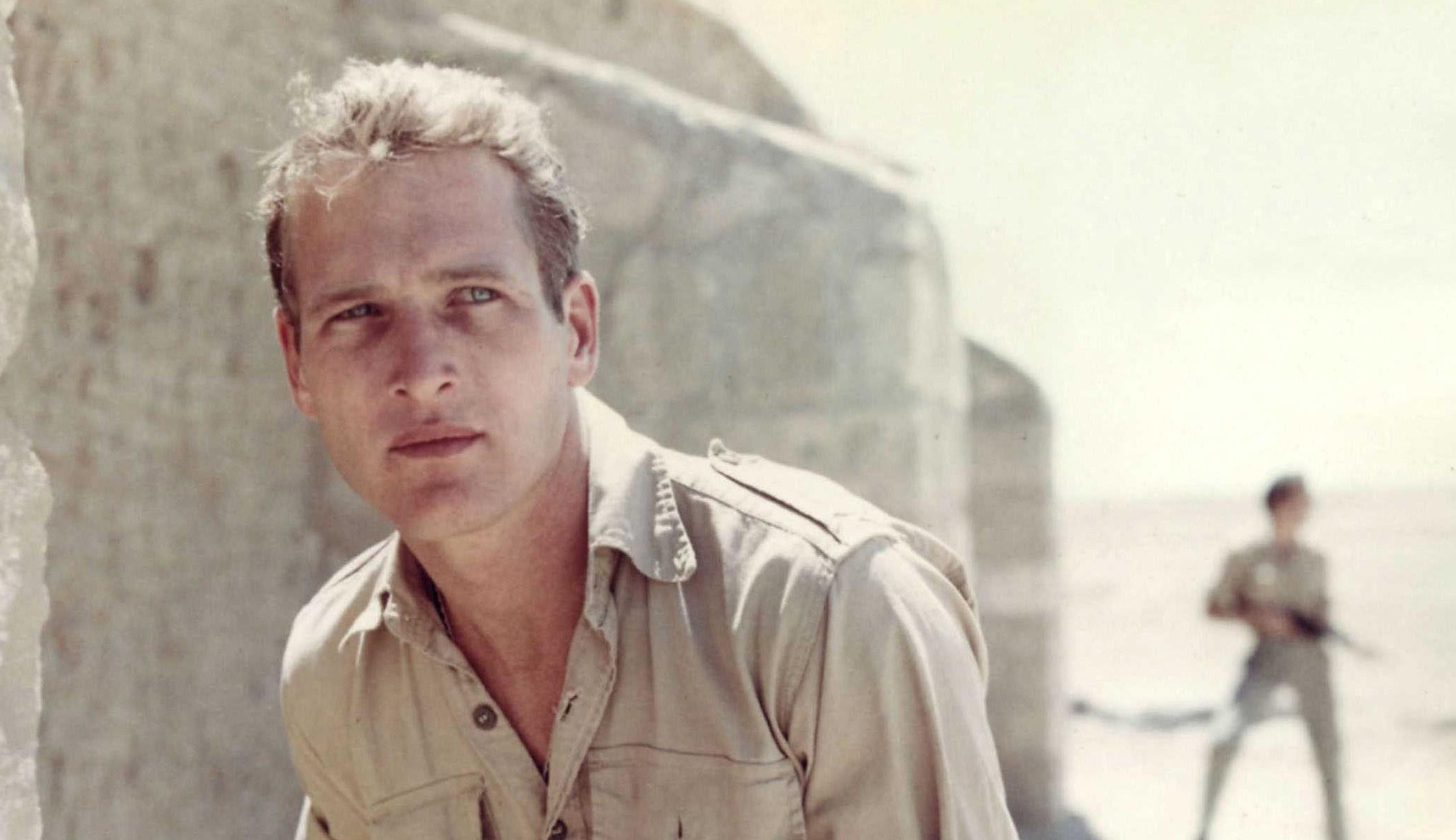

Sword in the Desert was followed by other attempts. The Juggler, released in 1953 by Columbia, was the first American production to film in Israel. Adapted by the screenwriter Michael Blankfort from his own novel and produced by Stanley Kramer, known for liberal “message films” including Judgment at Nuremberg and Inherit the Wind, the film featured Kirk Douglas as a Holocaust survivor who experiences a mental breakdown after his arrival in the state. According to the Yiddish scholar and musicologist Henry Sapoznik, The Juggler was “the first film to conflate Holocaust atrocities and the promise of Jewish healing in the newly formed state of Israel.” It reached the screen partly because of Douglas’s determination to portray the sort of strong, complicated Jewish characters that hadn’t been seen before.

As Chandler’s later career suggests, it’s also worth mentioning the Bible-inspired movies that flourished around the middle of the 20th century. A whole genre, of which The Ten Commandments (1956) is the most famous example, was devoted to retelling (and sometimes revising) stories from the Hebrew Bible. It’s true that these depictions were not specifically Jewish. The Coen brothers’ Hail Ceasar! (2016) brilliantly satirizes the studios’ efforts to satisfy a wide range of religious communities, with results that ranged from the anodyne to the absurd. Still, they brought Jewish characters, texts, and stories—including the connection between the people and land of Israel—new prominence.

To be fair, Richman focuses on commercially successful films that deal with the modern state of Israel. He starts with Exodus (1960), contrasting the movie version with the blockbuster novel by Leon Uris that inspired it. While Uris attempted, at perhaps tedious length, to locate Zionism in a history that extends back to biblical times, the film version reduced these connections to a few brief references. As Richman points out, it’s especially striking that the film substitutes a speech on the ideals of peace and brotherhood for a Passover seder as its final scene.

It isn’t easy to defend Exodus, whose greatest sin is not that it minimizes Judaism but that it’s not very good. Writing in The New Yorker, the critic Roger Angell observed that the director, Otto Preminger, “permits nearly everyone in his large cast to state his ideological and political convictions before and after each new turn of events, and the result is an awesome talkfest that is all-too-rarely interrupted by the popping of rifles.” As Richman notes, the most memorable element of the film is its Academy Award-winning score, which includes lyrics by a young Pat Boone.

Still, it’s worth reflecting on the different political economy of a novel and a major feature film. Apart from the author’s food and lodging, the cost of writing a novel is essentially nothing. Uris wanted and got a hit. But he did not have to worry about attracting or satisfying investors. Making a movie was different, particularly at a time when production and distribution were much more capital-intensive than today. To justify massive investments in cast, crew, equipment, travel, and so on, studios needed to appeal to the widest possible audience—internationally as well as nationally. Moral and political sensitivity may have played a role in the decisions that neutered Exodus. But it’s likely that the biggest consideration was making money, which the film successfully accomplished despite its unsatisfactory artistic qualities.

Further, it’s not as if Jews and Israel are the only people or country to see Hollywood transform their stories of doubt and faith, suffering, and triumph into pabulum. In 1961, the year after Exodus was released, audiences flocked to see Charlton Heston (a/k/a Moses) portray Don Rodrigo Diaz de Vivar, better known as El Cid. The film of that name, which is set amidst 11th-century wars between Muslim and Christian forces in Spain, concludes with the two armies joining together in prayer to the God they all revere. Despite the difference of period, setting, and participants, it’s almost exactly the same message as Exodus.

This example points toward a deeper, although not contradictory, explanation of Hollywood’s preference for universalism than the economic one I mentioned.

America, as Tocqueville famously insisted, is defined by democracy. And democracy, whatever its institutional expression, is based on the premise that all human beings are equal. To be a democrat, in other words, is to believe that everyone is, in the most fundamental, the same.

It is theoretically possible to combine belief in essential similarity with an appreciation for difference. A small industry is devoted to reconciling those premises. To be equal, on this view, means enjoying the same freedom to develop and uphold different ways of life, not only as individuals but also as communities. Expecting everyone to behave in the same way seems fair, but actually imposes the norms of one cohort on all the others.

This counterintuitive strategy comes in both left- and right-wing flavors and enjoys considerable popularity among academics and others inclined to dialectical argument.

The more common tendency, though, is to treat cultural, political, and religious differences as decorative, like colorful clothing that can easily be stripped off to reveal the less differentiated humanity beneath. The result of that tendency is that when democrats contemplate different societies, they tend to see versions of themselves.

While universalism is a recurring feature of democratic societies, it has been particularly intense in the United States. Until about the First World War, the ideal American was widely understood to be an Anglo-Protestant. So long as they counted as white, people of different ethnic and religious background were not systematically excluded from the mainstream of American life. But they were expected to conform as closely as feasible to Anglo-Protestant models.

In the 1920s and 1930s, however, theorists of pluralism developed a different understanding of assimilation. On this view, it was essential to adopt principles that could be equally applied to all Americans—and ultimately to all human beings everywhere. But it was not necessary, and perhaps undesirable, to feign the manners of a New England Yankee rather than adapting other experiences to democratic life.

A pluralistic version of American national identity was particularly suited to the international role that the United States acquired during the Second World War. Rather than portray themselves as imperialists like their rivals (and some of their allies), Americans sought to portray themselves as democrats leading a voluntary coalition of independent peoples struggling to uphold the same principles despite the ultimately superficial differences among them.

This understanding of world politics, which was less a fully articulate ideology than a form of moral persuasion, provides the background for Hollywood’s engagement with Israel. To avoid public backlash, the disproportionately Jewish leaders of the movie business likely did wish to avoid too close association with their religion, co-ethnics, or ancestral homeland. But they weren’t very interested in other forms of particularity either.

Spielberg’s Munich was produced long after this period, of course. But the film has more in common with the heyday of democratic pluralism than its dour mood suggests. For Spielberg, like the midcentury Hollywood that provided his true education (a process dramatized in the autobiographical The Fabelmans, which mostly effaces Spielberg’s religious upbringing), difference is colorful but ultimately superficial. Political leaders and institutions, to the extent that they appear at all, are corrupt. Instead of complicated ideologies, the protagonists are led by their conviction the difference between right and wrong is obvious, even if the means to achieving justice may not be.

It’s probably not coincidental that so many of Spielberg’s heroes are children. It’s probably also not coincidental that Spielberg, more than any other filmmaker, is responsible for the cult of the Greatest Generation as the highest exemplars of American—and therefore universal—values. Actual participants in the events Spielberg depicts have a different recollection of what the literary critic and historian Paul Fussell called “the boy’s crusade.”

To return to Israel: I understand why Richman is disappointed in most of the portrayals he finds on screen. But looking for profound depictions of Jews or Israel in mass-market cinema is a bit like looking for cowboys and Indians in the book of Exodus because both of those dramatic narratives take place in the desert. There’s an elective affinity but nothing like a realistic correspondence.

We should be grateful that the maturation of Israeli culture and lowered costs of film production have provided us with more accurate, insightful, and, frankly, more interesting efforts. But let’s not be too hard on America or Hollywood, where Herzl’s phrase “if you will it, it is no dream” has always meant something very different than it does in Jerusalem.

More about: Arts & Culture, Hollywood, Israel & Zionism