Edward Rothstein’s reply is a seminal essay on the “defensive retreat” into a “utopian dream of transnational universalism,” in the false hope of avoiding anti-Americanism, anti-Zionism, and anti-Semitism by abandoning the mission “that America once projected and that Jews (and Israel) have represented.”

He sees the retreat not only in Exodus and Munich, but also in Saving Private Ryan and The Fabelmans, and he finds Top Gun: Maverick an “intriguing hybrid”—“the type of hero and the type of victory that have long been associated with America and Israel,” but also, like Saving Private Ryan and The Fabelmans, a retreat into individualism. Indeed, he writes, Top Gun: Maverick champions “the rule-breaking individual, the maverick who ignores the chain of command.”

Mr. Rothstein ends his astute analysis by concluding that this defensive retreat is ineffective: “the hatreds of [America and Israel] persist no matter how we might try to avoid them and retreat into the universal.” One might take his argument even further and observe that such a retreat is also counterproductive. In 2018, at a Poland-Israel Hanukkah reception, held as a joint celebration of 100 years of Polish and 70 years of Israeli independence, Israel’s then-ambassador Ron Dermer noted the danger of the retreat into the universal:

We live in a world in which many believe, particularly young people, that all that separates us must be eliminated. They believe that our different faiths and nationalities, cultures and traditions, are merely artificial barriers that sow hatred and conflict.

But we must never forget that what separates us is also what makes us. It is makes us Poles and Israelis. It makes us Christians and Jews. It gives meaning to our lives and purpose to our future.

We must never allow differences in nationality, religion, race or anything else to prevent us from treating our fellow human beings with dignity and respect. . . . But we must also never abandon our unique identities. For a nation that does not embrace what makes it unique will not long survive as a nation.

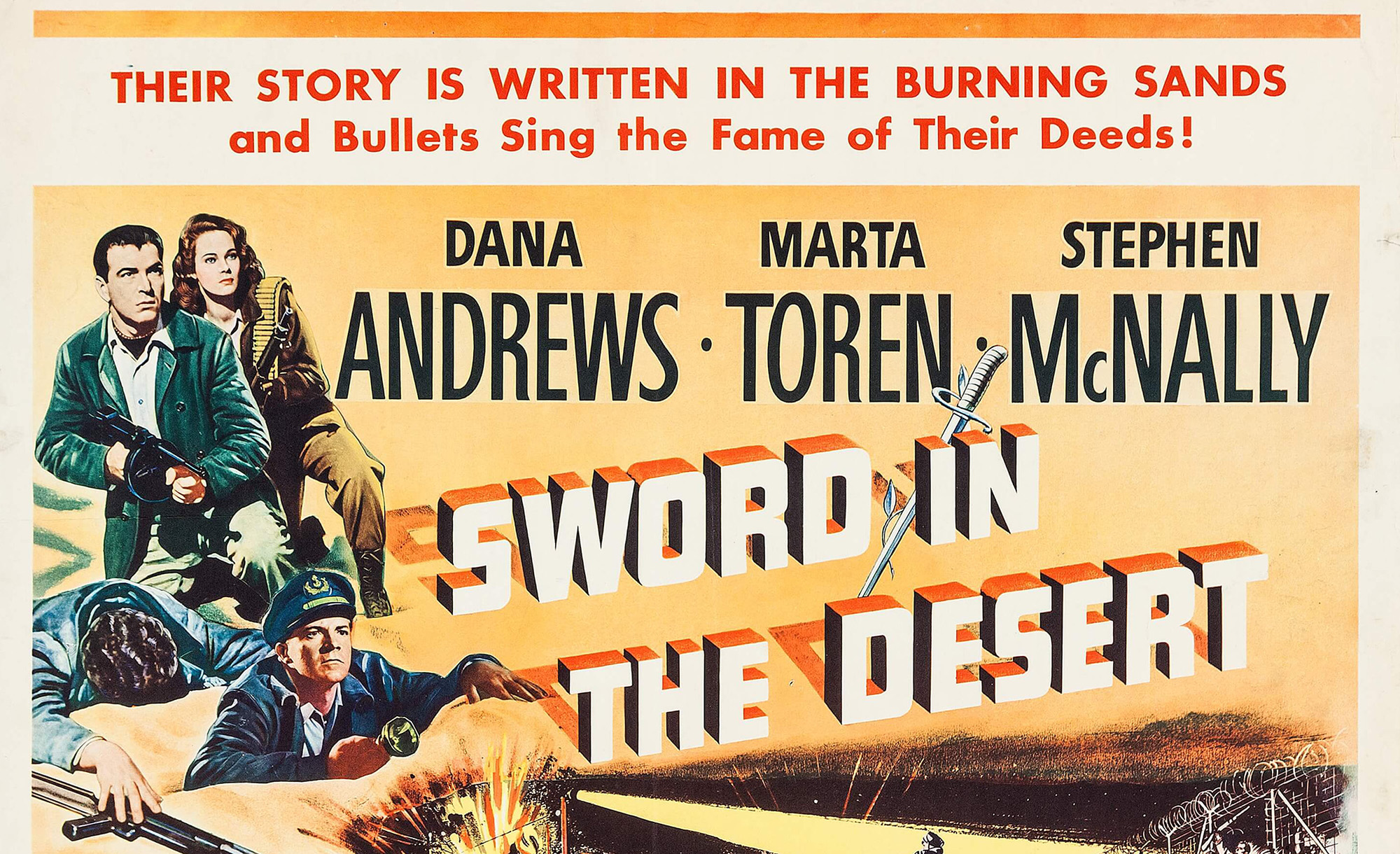

I thank Samuel Goldman for his thoughtful reply and his citation of additional Hollywood movies about Israel, which I believe reinforces the point of my essay: they too stray in varying ways from the underlying history. Tony Shaw and Giora Goodman have a useful discussion of these films in their 2022 book, Hollywood and Israel: A History.

Goldman argues that the “greatest sin” of Otto Preminger’s Exodus is that “it’s not very good.” He suggests that “the decisions that neutered Exodus” might be the result of “moral and political sensitivity.” But I do not think “sensitivity” explains the intentional omission of key scenes in Uris’s book, the creation and insertion of highly unlikely new ones, and the transformation of the movie into something significantly different from the novel.

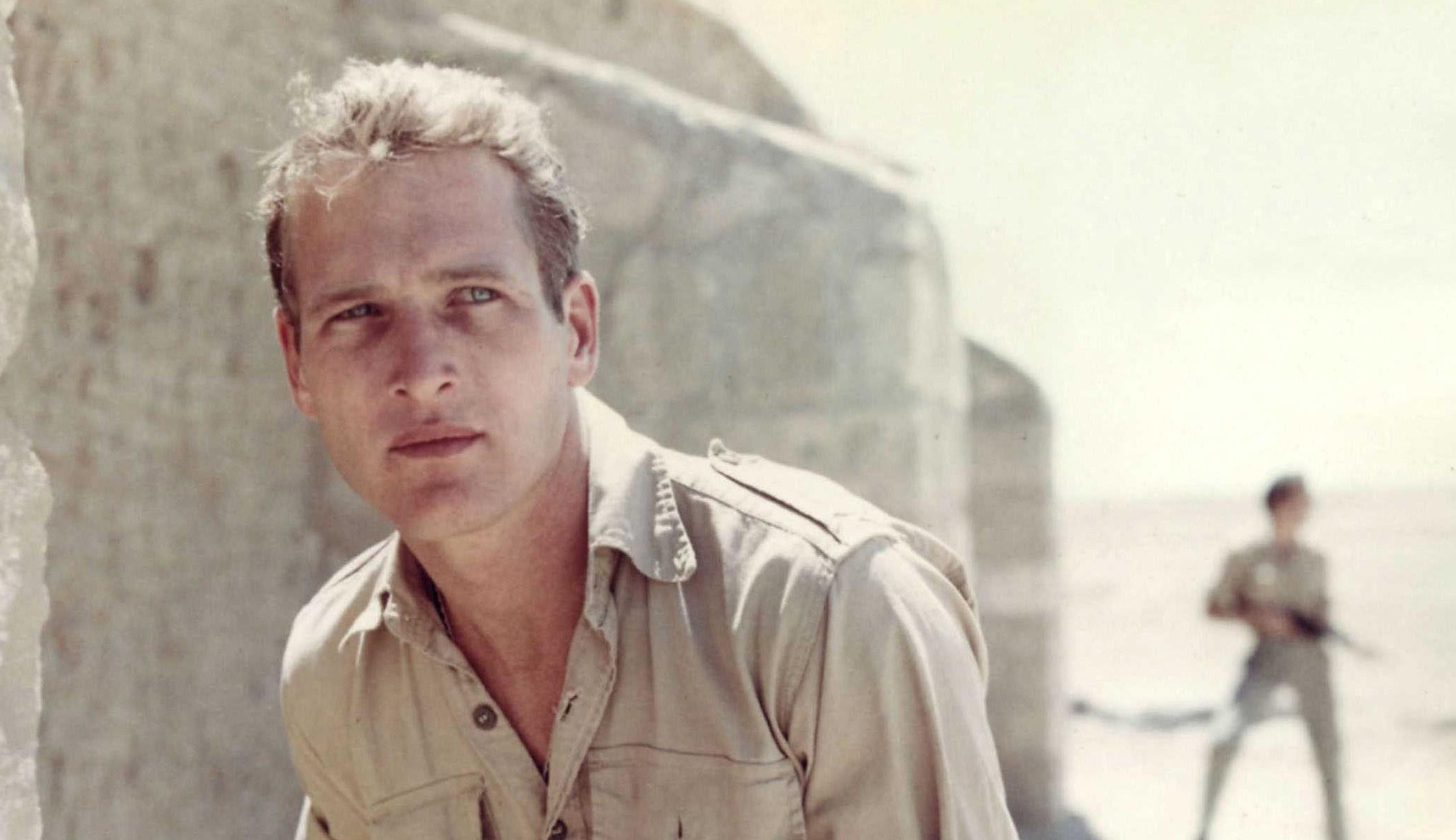

Nor were these steps necessary for box-office success: tickets were pre-sold on a reserved seat basis, and the profits were virtually guaranteed by the fact that millions of readers had bought the book in the two years before the film’s release—and that its lead characters were played by two of Hollywood’s biggest stars. Especially since the script was changed after Preminger received threats while producing the film in Israel, it’s hard to conclude that it was not a defensive retreat.

While preparing my January essay, I read the Uris novel for the first time, having been educated in college to believe it was not great literature and thus not worth my time. But my wife convinced me I needed to read it to research the essay, and my brother still recalled the power of the novel decades after reading it. I found the experience comparable to the one Midge Decter had in 1961, when she reluctantly began to read the novel and found herself staying up all night to finish it.

Once the novel sets its stage, introduces its characters, and begins to develop its story lines, it becomes a page-turner that is also immensely informative, skillfully presenting many episodes in modern Jewish history. I hope Goldman’s description of its length as “perhaps tedious” will not discourage new readers from seeking it out, or teachers from assigning it to students.

As for Munich, I do not think the putative connection that Goldman draws with the “heyday of democratic pluralism” half a century before explains the significant problems with the movie. In contrast to Exodus, the greatest sin of Munich is that it is extremely well made, making its misrepresentations of the underlying Israeli history a much more serious issue than those of Preminger’s Exodus.

Goldman does not discuss Top Gun: Maverick—a truly great movie that presented an Israeli story without mentioning Israel—but Hollywood could have presented its American hero while still acknowledging the underlying Israeli history, simply by adding a brief statement at the end, just before the credits:

In 1981, eight young Israeli pilots flew their F-16 planes for hours, deep into Iraq, often at a mere 100 feet above the ground, to bomb the heavily fortified nuclear facility being built by Saddam Hussein, in a two-minute strike just weeks before the facility would have become operational.

To accomplish their mission, the pilots needed to take their planes dangerously beyond the maximum distance specified by the manufacturer. But the mission was a complete success, and all the pilots returned home safely.

In addition, a character in the film could have said he had heard somewhere that Israel had done something like this four decades before—which would have added dramatic punch to such a factual statement at the end of the film.

But a studied avoidance of national specificity was obviously part of the film’s marketing strategy, perhaps because of the need to distribute the film on a worldwide basis, or perhaps because the filmmakers sought only to convey a tale of characters pushing themselves to the limits, with no connection to any national or international issues.

While I would not say, as Goldman does, that “looking for profound depictions of Jews or Israel in mass-market cinema is a bit like looking for cowboys and Indians in the book of Exodus,” he is correct to note that it is unrealistic to expect complete historical accuracy from Hollywood. But this does not mean that we must ignore all inaccuracies, particularly when they shape perceptions of important issues of the day.

The film critic Richard Grenier once noted that he did not care that “Shakespeare’s ‘histories’ are strewn with errors [and that] neither Eisenstein’s Battleship Potemkin nor his October recounts historical episodes in anything like the manner in which they actually occurred.” Yet, Grenier continued, a “great deal depends on whether the historical events represented in a movie are intended to be taken as substantially true, and also on whether they are seen as having a direct bearing on courses of action now open to us.”

Movies hold an immense power over the American imagination, and probably do more to shape perspectives on the world than the media, including social media, let alone books. The essays by Rothstein and Goldman thus serve to remind us of the importance of insuring that our children and grandchildren are educated about Jewish history and the Jewish state somewhere besides a movie theater.

More about: Hollywood, Israel & Zionism