In 1882, the Russian physician Leon Pinsker challenged the Jews to reclaim their own destiny and build a society in the land of Israel. Where Theodor Herzl later thought that the Jews needed recognition from world leaders to do that, Pinsker thought that the Jews of the diaspora should start by picking up and relocating on their own. To him the solution to the Jewish question was to build something new—without asking permission. Both ways, diplomacy and boldness, are needed—but which is needed when? That’s a question worthy of close attention and study right now.

To explore that question, and to think about what Pinsker’s Zionist legacy can offer today, Mosaic invited the author of our May essay on Pinsker, Aaron Schimmel, to talk with the Israeli historian Daniel Polisar and the former Israeli MK Einat Wilf. Their conversation took place on Wednesday, May 24, at noon Eastern time via Zoom. Watch the recording below.

Watch:

Read:

Jonathan Silver:

Welcome. It’s just after 9:00 AM in Palo Alto, just after noon here on the East Coast, and 7:00 PM in Israel. My name is Jonathan Silver. I’m the Warren R. Stern Senior fellow of Jewish Civilization at Tikvah, the host of the Tikvah Podcast and the editor of Mosaic, which, earlier this month, to celebrate the 75th anniversary of the recovery of Jewish sovereignty in the Land of Israel, published an essay on one of the founding personalities of modern Zionism—the essay that we’ve come together to discuss, portraying the author of the pamphlet Auto-Emancipation, Leon Pinsker. The essay is called “Herzl Before Herzl.” Its author, Aaron Schimmel of Stanford University, is with us today. And we’re also joined by two distinguished guests, Dr. Einat Wilf and Dr. Daniel Polisar, about whom more in due course.

I’d like to introduce our session by explaining why it’s important for us at Mosaic to focus on Zionist history. The Jewish people in just a matter of hours is poised to begin our celebration of Shavuot, which marks our reception of the Torah at Mount Sinai. The reception of the Torah at Mount Sinai is considerably more than what is sometimes called by philosophers: Revelation. It’s not as if the Jewish people received a divine text message that they could then put in their pockets and ignore. For in the biblical recounting, the Jewish people affirm a covenant with God for all time, binding upon not only the thousands of women, men, and children standing there at that moment, but upon their children and their children unto this very day. Which is why, 49 days before Shavuot, we gathered as families to acculturate our children into the story of our national liberation from Egyptian oppression, and why in just a few hours we’ll return in our moral and historical imagination beside our ancestors and inhabit our place in the covenantal destiny of the Jewish people.

The way that happens is through the telling and retelling, reliving and relearning, of our national story. And although the history of Zionism is not the same as Jewish religious history, we can learn from the moral and civilizational strategies that our religious tradition offers to inculcate a similar kind of fidelity to the miraculous but also human achievements of modern Zionism. Today we learn about one of its founders, Leon Pinsker.

At Mosaic, we publish some of the outstanding senior scholars, writers, and rabbis in the world, but it’s important to us also to seek out rising scholars and work closely with them to bring out their best thinking and writing. So part of our mission is to disseminate the work of the Daniel Polisars and Einat Wilfs of the world, but part of our mission is also to find and work with young, rising talents. And I want to congratulate the author of “Herzl Before Herzl,” Aaron Schimmel. Aaron’s work, my work, our work at Mosaic is simply not possible without our subscribers who, along with the editors and the writers, form the third leg of our communal stool. If you are a Mosaic subscriber, thank you for being a part of our community of ideas, thank you for making this essay, and this event, possible. If you’re not yet a Mosaic subscriber, please, I encourage you to join us.

Let me offer a special thank you to members of the Mosaic Editors’ Circle and to members of the Tikvah Society who stepped up to lead our communal efforts. Thank you.

Joining me and Aaron today is Dr. Einat Wilf, a leading English- and Hebrew-language exponent of Zionist ideas and academic, a former member of the Knesset, and the author of many books, including The War of Return. And also Dr. Daniel Polisar, the co-founder and executive vice-president of Shalem College, formerly the president of the Shalem Center, which is where I first got the chance to meet him. Dan is the teacher of Tikvah’s online course on the life and statesmanship of Theodore Herzl, and he’s the host of a new limited-series podcast, Building the Impossible Dream, which is a thirteen-episode history of Zionist ideas and politics. You can download it for free wherever you get your podcasts.

First I’m going to ask Aaron to speak for a few minutes and restate the main contentions of his essay and introduce us to Pinsker, to what got him interested in Pinsker, and to what we should learn from Pinsker now. We’ll then turn to Dan and Einat and have a short conversation together. And then we’ll have a few minutes for Q&A. Aaron, let me hand it over to you and let’s hear what “Herzl Before Herzl” is about.

Aaron Schimmel:

Thank you so much for having me here and for being part of this conversation. I think Pinsker is important, and I think he doesn’t quite get the attention that he deserves, especially in America. In the essay, I make two interrelated points. The first is simply that Pinsker has been overshadowed by Herzl and other later Zionist leaders, and deserves our attention. Zionist history tends to be told from the great-man perspective, through a series of important figures. And that is indeed a very useful way of looking at Zionist history. But I think that there is another perspective which focuses on the unnamed masses, the Jews who picked up and left their lives in Eastern Europe, or in Western Europe, and came to the Land of Israel and built a society there. Those Jews, and not just Pinkser himself, are part of the story I tried to tell in the essay.

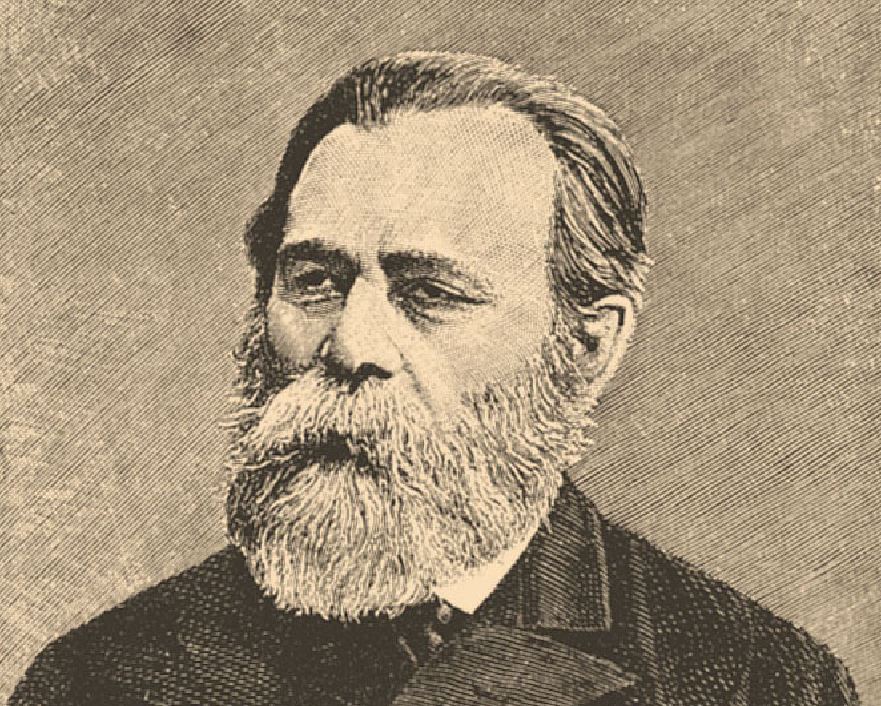

Let me start with Leon Pinsker and his background. Pinsker spent most of his life in Odessa, in the Russian empire, a fact that had profound impact on his worldview and his relationship with Judaism. Odessa at the time was not like the shtetl. It was very cosmopolitan. Jews in Odessa tended to be more outward looking, more integrated into the outside world. Pinsker was raised by a prominent maskil, an enlightened Jew, who was a proponent of giving Jews a broader education than what they would receive in the traditional Jewish education system. This involved learning the German and Russian languages and reading great works of literature outside the Jewish canon.

This is how Pinsker was raised. And as a result of this education, he was able to become a doctor. He spent most of his life working as a physician. He volunteered during the Crimean War in the 1850s to be a doctor with the Imperial Russian army. As part of the Russian maskilic project, there was a great interest in emancipation, meaning the granting of both political and civil rights to Jews. This is a process that was happening all over Europe, and Russian Jews were looking at the Jews of Western Europe—who had been granted rights over the course of the late 18th and 19th centuries—and aspired to gain similar rights in Russia.

How did they think that they could earn emancipation, earn equality? By integrating into Russian society. Not necessarily fully assimilating or losing their distinctiveness. Pinsker himself was never what we would think of as fully assimilated. He always was interested in Jewish affairs; he published articles in Jewish newspapers; he was involved in organizations that sought to spread enlightenment to Jews and to give Jews access to secular education. But he was also involved in Russian life. As I said, he volunteered in the tsar’s army. He was familiar with Russian literature and thought. He was up-to-date on the news. He’s a great example of the Russian maskil who was hoping that by living in this way, he could help pave the way for emancipation.

This worldview was shaken dramatically in 1871, when a pogrom broke out in Odessa and drove Pinsker to begin a process of rethinking his outward-looking worldview. Because if a pogrom could happen in Odessa where Jews were integrated into the non-Jewish society surrounding them and interacting with the Jews around them, then integrating might not be the way for Jews to receive emancipation. This initiated an about a decade-long process, which we don’t know much about—because in this time period, Pinsker published very little. But another set of pogroms broke out in 1881, and this became the moment that this long process of rethinking was completed. Pinsker and other Russian maskilim looked towards non-Jewish Russians, especially non-Jewish Russian progressives who, up until that point, had been champions of granting equality. And these non-Jewish Russians had nothing to say. They didn’t come to the Jews’ aid.

Radicals looked at the violence as the non-Jewish working class rising up against their Jewish capitalist oppressors, and at times even urged it. This betrayal in particular shook Pinsker, and completed this long process of rethinking his ideas about integration and emancipation. As a result of this reevaluation, he publishes Auto-Emancipation, which is primarily critical of what his previous worldview had been. It looks at Jews and non-Jews and argues that anti-Semitism is not going away. It can’t be expected to fade. Whatever the Jews might do, it will still be there. As a doctor, he views anti-Semitism in medical terms and calls it a hereditary disease. He observes that the Jews are a ghost of a nation. They’re the strangers par excellence because they have no home; they lost their territory. And he say that it’s natural for people to be afraid of ghosts, and the Jews are a ghost. And so the answer here is to become a nation again.

Pinsker observes Jews in Western Europe who have been emancipated and, in one of his most striking lines, reminds them that their rights are entirely reliant on the goodwill of the non-Jewish authorities. These rights can be, and in certain situations were, retracted. And so he proposes a collective national solution to the collective national problem facing the Jews. Integration, his previous plan, was something that individuals do, but the revival of the nation and the creation of a Jewish state is a collective response.

To be clear, not all Jews will live in this new state, according to Pinsker, but the very existence of it will provide both a refuge for Jews who are struggling and a revival of the national spirit, so that even the Jews that remain in the diaspora will appear less ghostlike. Anti-Semitism will not go away, but it will ease up a little bit. And Pinsker becomes involved in an organization called Ḥovevei Tsiyon, which oversees early settlement activity in the Land of Israel. Young Jews in Russia, mostly students, observe the pogroms and come to similar conclusions as Pinsker. They’re inspired by Pinsker’s work, and they get up and go to the Land of Israel and start small agricultural settlements. And because they have a great deal of trouble supporting themselves and life in the land is difficult, they rely on philanthropy from Jews in the diaspora, and specifically from Ḥovevei Tsiyon.

Ḥovevei Tsiyon is also involved in purchasing land and starting new settlements. The process of land purchase was done legally. The process of individuals entering the land and settling was largely done under the radar of the Ottoman government, which controlled the land at the time. This approach followed Pinsker’s auto-emancipationist view that Jews must act as they need to for the good of the nation without relying on the goodwill and help of non-Jewish authorities. And so, rather than waiting for the Russian empire to grant emancipation, rather than getting permission from the Ottoman empire for Jews to settle in the land, the spirit of these early pioneers was to get up and go.

Let me now address Herzl, who is obviously quite important. Herzl’s plan for political Zionism, his strategy for attaining a state, is by contrast largely diplomatic. Herzl makes great efforts to meet with the Ottoman sultan and with the German Kaiser with the intention of attaining a charter for a Jewish state from these political authorities. Both of these meetings essentially come to naught. Herzl is very important in making the Zionist movement a much broader movement than it was before him. And he had a clear vision for the future, which Pinsker lacked. And this was very important for attracting broader support from Jews throughout Europe. But his diplomacy achieved little in his own lifetime.

And there are other reasons that Herzl overshadows Pinsker. For one, the early settlements overseen by by Ḥovevei Tsiyon were very small. And it’s estimated that about 50 percent of the early pioneers who settled in the land, after confronting the reality of how difficult life was, moved on to America or returned to Russia. Another reason why Herzl overshadows Pinsker is that Pinsker was a very quiet man, very taciturn. When he wrote for the Russian Jewish press, he often published anonymously.

This is very different from Herzl who was very charismatic. He had a flair for showmanship, he was young, attractive. Pinsker was at the end of his life. He passed away in 1891. And Herzl is traveling throughout Europe, meeting with high-profile figures. Three are stories of Herzl arriving in towns throughout Europe and the local Jews coming out in droves to meet him. People named their children after Herzl. He was even accused of being a sort of pseudo-messianic figure, of having too much of a cult of personality around him. But these aspects of his personality make him easier to study, whereas Pinsker fades into the background.

As I explain in the essay, Herzl and Pinsker embody two different approaches to Zionism. Pinsker’s auto-emancipationist approach states that the Jews need to get up and go to Palestine, and start establishing their national life there. Jews need to take the initiative. Yes, having support from non-Jewish authorities is nice. It’s even essential, but it is not what the Jews can rely on. Ben-Gurion, who I argue is very much rooted in the auto-emancipationist model, turns to the UN for recognition for the state of Israel. But ultimately he believed that Jews need to be master of their own fate, and win national freedom for themselves.

For Herzl, on the other hand, the path to a Jewish state required the help of non-Jewish authorities. The Ottoman sultan was supposed to grant a charter for the Jewish state. On the eve of statehood, Ben-Gurion, by contrast, is involved in organizing illegal immigration—getting Jews into the land after the British had attempted to limit Jewish immigration. He is involved in the Haganah, the pre-state defense force, which actively resisted British mandate rule. And in contrast to this, Chaim Weizmann, Herzlian to the core, maintains his faith that the British government will help create a Jewish state, and make good on their promises in the 1917 Balfour Declaration that the Jews will have a national home in Palestine.

And so it was the confluence, the interplay, of these two approaches that was essential for creating the Jewish state. High-profile diplomatic activity is crucial in making the cause known and gathering support. That’s important. But without those who arrived early, in the First and Second Aliyah—the first migrants that built a society in the Land of Israel—what came after could not have happened. And what came after, the fact that there was a state waiting to be officially recognized when the British mandate was terminated in 1948, is what allowed Israel to survive its earliest years, and to grow and flourish as it has for the last years.

Jonathan Silver:

Aaron, thank you for that. I think, to draw out some of the enduring themes that we locate in Pinsker and that you analyze in the essay, you could say that there are points of contrast and points of continuity among Pinsker’s successors, most notably, perhaps the most important single Zionist of his generation, Herzl. And whereas Pinsker thought that establishing the presence of Jewish women and men on the ground in the Land of Israel had a kind of moral and spiritual purpose for them and for their connection with the land, it would also move politics in a certain way or at least reconstitute the national identity of the Jewish people. By contrast, you note that Herzl thought that diplomatic recognition of Jewish sovereignty in the Land of Israel was a strategic necessity.

And of course, these visions are not in tension with one another; both would be necessary in time. But you can also see that there’s a different point of emphasis. Second, there’s an important Zionist doctrine that the establishment of sovereignty in the Land of Israel, in the state of Israel, would be one of Zionism’s final achievements, but that sovereignty would be laid over an intact civil society with most of the institutions of government already in existence. And this is a different approach to nation-building than seeking sovereignty first.

I suppose one thing that I would like to ask you to clarify is Pinsker’s diagnosis of anti-Semitism. Because there are places in Herzl’s writing where this is a real point of contrast, where Herzl thought that the whole problem of the Jews is that they’re looked down upon because they don’t have a state, but if they were to have a state, then the dominant aspects of anti-Semitism could disappear. Whereas, somewhat like another successor, Jabotinsky, it seems that Pinsker thought that anti-Semitism would endure even when there’s a state. It’s just that that state could provide a protective function for the Jews.

Aaron Schimmel:

I think one explanation for the contrast between the Jabotinsky/Pinsker approach and the Herzl approach is where they came from. Herzl is from a supposedly enlightened German-speaking territory. He spends much of his time in Vienna; he lives in Paris. And so there are enlightenment values about human dignity and things of this sort floating in the air. And even though anti-Semitism exists and there’s the Dreyfus affair and Karl Lueger who’s the anti-Semitic mayor of Vienna—Herzl is living in a very different atmosphere than Russian Jews.

For Herzl, these manifestations of anti-Semitism are new, and suggest something’s out of whack. In Russia, the situation is totally different. The talk of equality and human dignity and things of that sort is limited to intellectuals, to the well-educated. These aren’t values of a broader society in the same way that they are in the West. And the Russian Jews look at their history, and see it as one of unending anti-Semitism, to varying degrees at different times. They are used to being treated as a separate legal entity, to living under separate laws.

So Russian Jews have a sense that this hatred is going to be around forever. They don’t really trust that anti-Semitism is going away because when they look at the West, they see that, yes, it went away in France and in Germany for a while. And now at the end of the 19th century, it’s coming back. And so I think this convinces people like Pinsker and Jabotinsky (who is also from Odessa) that it’s there to stay, and anti-Semitism will exist in varying degrees no matter what. If the Enlightenment and the progressive West couldn’t get rid of it, then how are they supposed to expect that it’s going to go away in Russia?

Jonathan Silver:

I want to come to Einat in just one minute, but my last question for you, Aaron, is: can say something briefly about Pinsker’s attitudes toward religion?

Aaron Schimmel:

I mentioned that Pinsker comes from a maskilic background. And a core feature of that is leaving behind the traditional religion of the shtetl, and a rejection of what the Haskalah saw as the irrationalism of Ḥasidism and Kabbalah, and an embrace of a more rationalist approach to religion. And the Haskalah also rejects pilpul, dialectic study of the minutiae of rabbinic texts, and places a greater emphasis on studying the Hebrew Bible. And at the same time, religious practice is not necessarily something all that important to the maskilim.

Now there is a religious faction of Ḥovevei Tsiyon, and there’s great tension between the religious and secular factions of the movement. Many of the pioneers, the first settlers, are young secular Jews who are not interested in practicing Judaism. And for the religious elements of Ḥovevei Tsiyon, they don’t want to be supporting, financially and otherwise, secular Jews because they are religious and they believe that Jews should live a religious life. But I think in terms of the Jewish collective, as far as Pinsker views it, having a territory and this shared historical background that goes back to Jewish sovereignty in the Second Temple period is far more important to him than religion as a basis of Judaism.

Jonathan Silver:

Thank you, Aaron. Einat, you’ve been studying Zionist history forever, and are one of its best representatives on the world stage. Tell us what you make of Aaron’s essay, his presentation, and of Leon Pinsker.

Einat Wilf:

Thank you for the opportunity to participate here. And thank you, Aaron, for your essay, and to Mosaic for publishing it. First, I have to say that I commend any and every effort to bring the story of Zionism to an English-speaking audience. This is certainly something that has motivated me for many years because it’s the best response that we have to an attitude that unfortunately also exists among people who love Israel, and sometimes even Jews, to think that Israel is somehow the outcome of the Holocaust. If I put it in an almost cartoonish way, it’s the notion that Israel is somehow a gift by guilty Europeans after World War II.

As you all know, guilt was not the overriding emotion of Europeans after World War II. And again, the whole notion of Israel being a gift to Jews after the Holocaust creates a lot of secondary elements. If Israel is a gift, then it could be taken away when Israel doesn’t behave properly. Or that Palestinians are the secondary victims of Europeans’ crimes.

Anything that helps demonstrate that it’s the Jews themselves who envisioned the state, who had the idea far earlier, who took steps—whether diplomatic or on the ground—in order to make it a reality, I think is an incredibly important project. It’s a way to counter this very dominant and completely wrong idea that I have come to call over the years Zionism denial, because it denies precisely the thing that I think is most central to Zionism, which is agency—the fact that the Jews took it upon themselves to change the course of history. And Zionism denial, the notion that Israel is a gift, robs the Jews of the most important element of Zionism, which is the idea of agency. Whether it is Auto-Emancipation, which is literally about the idea of agency—we’re emancipating ourselves—or Herzl’s actions, I think the more that can be done to bring this part of the story to the English-speaking audience is valuable precisely as a means to counter that narrative.

Now I have to say, having grown up in Israel, that there the story of Zionism is actually told—maybe influenced by Ben-Gurion and others—starting with 1882. I remember in 1982 in school we celebrated a hundred years of Jewish immigration. It takes you about several decades later to grow up and to realize that those were about twelve people who came to Israel at the time, but we celebrate that as the beginning of the First Aliyah.

So when you study Zionism, certainly when I did in the Israeli school system, in the secular state-run school system, you start with the First Aliyah of the 1880s, then the Second Aliyah [beginning in 1903], then the third [1919–1923]. You actually learn the story of Jews. You also learn the story of Herzl. But the far bigger story is the story of immigration, and it’s told as the story of a group, of the people, rather than what Aaron called the great-man view of history. This is how I grew up learning Zionism. Herzl has his place, but, under the influence of Ben-Gurion, Zionism is the story of aliyah.

The other thing then I have to say is, once you put all that together, trying to draw the differences between Herzl and Pinsker at some point begins to be a little too much of splitting hairs. I don’t think that they really represent two very distinct approaches. Their approaches ultimately work together. Dan is definitely going to talk about this too, I’m sure. He beautifully lectured about it in his course, explaining that Herzl was as much an institution builder as he was a diplomat. If anything, the problem is that Herzl is known more as a visionary, as if he just wrote a book and then things happened, and not enough as an institution builder, which is in many ways by far his greater contribution.

With Pinsker, we see people had the idea of Zionism before Herzl. Much like in the business world today, ideas are a dime a dozen. Lots of people have ideas. But execution is everything. And what Herzl brings to the table is an incredibly high level of execution, not just on the diplomatic front, but really in building the institutions that would later underpin the modern state of Israel. So I think reducing him to his diplomacy is selling him short.

And maybe I’ll just end by saying that, on the issue of facts on the ground, in many ways, this is the biggest failure of Zionist movement. Herzl, with his work—and again, Dan lectured about it beautifully—brought about the Uganda/Kenya plan, which actually set the stage for the Balfour Declaration and the League of Nations mandate. Herzl through his vision posthumously achieved something on a global scale: the League of Nations mandate (which we should always emphasize more than the Balfour Declaration). This is the world saying unanimously, “We recognize the connection between the Jews and the Land of Israel, and that they possess the right to self-determination there.” The problem is that from that moment, and for the next decade-and-a half, the Jews are not coming to the land. They’re not coming in the numbers that perhaps would have allowed for the state of Israel to be established in the 1930s when it actually mattered.

At the end of the day, what really makes Herzl stand above and beyond everyone else is that he understood that the ground was burning in Europe—not just in Russia, but all over Europe—and that the Jews had to get out. And through his vision, the Jews got the mandate, but then they didn’t come. And because they didn’t come in time, the state of Israel was established too late. When we mark Yom HaShoah we say, “never again.” And I always argue that the state of Israel was supposed to have been established so that “never at all.” It was supposed to have been established in the 20s and in the 30s. And imagine if the Jewish state had gone to the Evian Conference [convened in 1938 to address the problem of Jewish refugees from Europe] and said, “We want them. We’ll take in all the refugees.”

Ultimately, I think that people don’t sufficiently recognize the responsibility born by the British and the Arabs in blocking Jewish immigration to the Land of Israel, in contravention of the League of Nations mandate. We have a comparable case study that helps us understand this. The Holocaust could have just been the ethnic cleansing of Jews from Europe into a state of Israel in the 30s. But because there was no state of Israel, it became a Holocaust. And we know this because of what happened in the 1950s and 60s when the Arab world engaged in ethnic cleansing of Jews. The only difference between Europe in the 30s and the Arab world in the 50s was the state of Israel. And because the state of Israel existed in the 50s, it was an ethnic cleansing of Jews in the Arab world and not a Holocaust. So at the end of the day, we got the diplomatic charter, but the Jews didn’t come in time.

Jonathan Silver:

Thank you, Einat. I’d like to invite Dan to offer some of his remarks as well, and then Aaron can respond to both of them together.

Daniel Polisar:

First, I want to join Einat in applauding Aaron. What you’ve done here is to take a figure who really is a great writer and a great activist and a real inspiration, but unfortunately has not, at least in recent decades, gotten the due that he’s deserved, and to have placed him back on the map for English readers. And I hope that has an impact on Israelis as well. I agreed with a great deal of what you wrote and enjoyed what you wrote, but it would not be interesting or educational or fun to focus on our points of agreement. So I want to put on the table briefly three points of what I hope will be friendly disagreement. I’m not going to say anything to denigrate Pinsker, that wouldn’t be appropriate and it wouldn’t be historically accurate. But I want to make sure that we do full justice to Pinsker while not reducing two other great figures who feature prominently in your essay.

The first point has to do with Pinsker as an author. Here I would urge you to back your guy even more firmly than you have. You write, “Auto-Emancipation was a powerful work in its own way, but one hurriedly written and lacking the stylistic verve and eloquence of The Jewish State.” Now, both Herzl’s, The Jewish State and Auto-Emancipation are powerfully written works. And I say, as somebody who loves Herzl—in fact, I see myself as a Herzlian to a very great degree—that the last time I taught both of these works, I confessed to my students that I actually found Auto-Emancipation to be the more profound work in its analysis. It is in some regards better written and more original and memorable. And you may or may not see it that way, but I don’t think that you need to concede to the Herzl lovers in terms of the quality of writing.

You note, correctly, that Auto-Emancipation was written quickly. But sometimes the best works are written quickly. You can feel Pinsker’s passion, his anger, his sense of disappointment. His life’s project was essentially trashed in a relatively short amount of time, and he was responding. I think he deserves a lot of credit as a writer—especially since he was by profession a doctor, whereas Herzl was a journalist and playwright, and you’d expect him to be a great writer. That’s the first thing.

The second thing has to do with Herzl’s views on Jewish self-reliance. And here, I want to echo what Einat said in her remarks. It’s true that, especially at the very beginning, Herzl placed a great emphasis on diplomacy. But when you write about it, I think you overstate it a bit. You write that, “The core idea of Auto-Emancipation is one that is crucial to the Zionist ethos: the Jews must take responsibility for their own fate and cannot rely on the beneficence of Gentile regimes. For all the similarities Herzl noted between Pinsker’s manifesto and his own, it is only Pinsker’s that makes this idea of self-reliance its centerpiece.” Herzl was a realist. He did not rely on or believe in the beneficence of Gentile regimes. He thought that there were overlapping interests between non-Jewish powers and the Jewish people, and that with the right kind of Realpolitik diplomacy, he might be able to find a point of agreement around the idea of creating some kind of a Jewish commonwealth. But I wouldn’t overplay his naïveté and I wouldn’t underplay his focus on Jewish self-reliance.

And here I’ll also echo what Einat said about Herzl as an institution builder, from the time of the First Zionist Congress in 1897 onward. Even in The Jewish State, most of what he writes about is very nuts and bolts. And I know that because reading it, and I say this as someone who loves Herzl, it’s kind of boring. It’s page after page about how we’re going to organize the societies, how we’re going to build the houses, how we’re going to move people from point A to point B, who’s going to get compensated for what, the number of shares in the Jewish company, and that kind of thing. He was a big believer in Jewish self-reliance, in part as a trigger for successful diplomacy.

The final point that I would make has to do with the question of lining up Ben-Gurion with Pinsker and Weizmann with Herzl. Weizmann learned a great deal from Herzl, but he also learned a lot from Pinsker. And Ben-Gurion learned a great deal from Pinsker, but he saw himself first and foremost as a follower, a devotee, of the ideas of Herzl. And this isn’t just a question of whose name they would’ve put on a piece of paper if asked, “Who’s your hero?” It has to do with the actual acts that these individuals carried out. And it’s true, Ben-Gurion is famous for saying “UM—Shum,” a clever Hebrew way of saying that the United Nations doesn’t mean much, and that what’s important is “not what the goyim say, but what the Jews do.” And in that sense, he’s Pinsker-esque, at least in your understanding. But at the same time, he was a big believer in the powerful diplomatic gesture.

You also talk about how the Declaration of Independence was Ben-Gurion, in a sense, channeling Pinsker. But far more than Pinsker, you could feel Herzl’s presence, not just because it was agreed by the Zionist leadership that the only picture in the room during the signing was going to be a portrait of Theodore Herzl, but also because he believed that you start with Jewish self-reliance—building the army and building the economy—about which Herzl wrote. But in Herzl’s view (and Ben-Gurion’s) there also needs to be that moment in which you bring about the grand gesture based on the UN’s recognition of the need to partition Palestine into two states. At the same time, Ben-Gurion issues the declaration without waiting for the UN to say, “Okay, go ahead and declare statehood.” Somewhat in defiance of what the UN probably would’ve liked, Ben-Gurion stands up in front of the entire world, and not just the Jews, and declares independence, and makes it clear that this isn’t just a statement, but something he plans to act on. That kind of bold diplomacy mixed with self-reliance, of declarations mixed with bold action, that is Herzl. It’s Herzl more than it’s anyone else, until it becomes Ben-Gurion more than anyone else. So I would’ve traced those lines a bit more closely.

Having said those things, your essay is an extraordinarily important contribution, and I’m pleased to have the opportunity to praise it, but also to challenge you on a few points.

Jonathan Silver:

Excellent, Dan. Thank you very much. Aaron, I do want to get to Q&A with our guests, but you should respond. I think Einat and Dan raised illuminating questions that help us penetrate Pinsker’s spirit even more deeply.

Aaron Schimmel:

Thank you both for your remarks. I’m happy to hear that in Israel there is more emphasis placed on Pinsker and on the early pioneers than there is in the U.S. I know that from my own American Jewish day-school experience, it was kind of a shock to me to learn about Pinsker. And shamefully, it wasn’t until I was in college that I was aware of all of this that was happening pre-Herzl. I hope that in America and elsewhere in the diaspora we can get a little bit more of that.

To the point that both of you make that I’m unfair to Herzl and I undersell the emphasis that he places on self-reliance—I don’t disagree. It’s something that I struggled with as I was writing, and had my own doubts about. But I do think the very fact that the diplomatic element is so prominent in Herzl’s writing, and absent in Pinsker’s, is significant. And it seems to me, through my reading, that Herzl places a greater emphasis on diplomacy and he sees the importance of the grand diplomatic gesture in a way that Pinsker is not really interested in at all. And that was striking to me. I’ll leave it at that.

Jonathan Silver:

There are a bunch of questions we’ve gotten that I want to get to. Miriam Hoffman writes, “Which Jewish organizations had the funds and the money to purchase land or support traveling Jews to the land of Israel and even organized the Three Kings Hotel [in Basel] for the First Congress, with Herzl heading it? How is all this funded?”

Einat Wilf:

With Herzl’s wife’s money.

Aaron Schimmel:

I can speak to some of the earlier settlements: Ḥovevei Tsiyon was working with Moses Montefiore or with Rothschild, I forget which. And both were very much involved in giving financial support to these early settlements. But they also relied on Jews throughout Russia. Ḥovevei Tsiyon had representatives go to different towns to preach Zionism and collect money from people. Of course, the contributions of the Montefiores and Rothschilds were much, much greater, but there are also contributions from the rank-and-file shtetl Jew who gives just a kopeck or a ruble.

Jonathan Silver:

Warren Stern asks if Pinsker addressed the option of migrating to America.

Aaron Schimmel:

In Auto-Emancipation, Pinsker argues that Jews should accept any territory that they can get. And in fact, he originally sees early immigration to the Land of Israel as a misguided effort, the outgrowth of the passions of the masses. It’s only a couple of years later, in 1884, when Ḥovevei Tsiyon is founded officially that he comes to appreciate this popular desire to go the Land of Israel, and sees the value of building up this Jewish territory in the ancient homeland of the Jews.

Jonathan Silver:

Dan, I want to address this question from Yehuda Eliasri to you, which asks, “For all of Herzl’s careful nuts-and-bolts writing in The Jewish State, to what extent did he himself ignite a passion in the people, in the Jews of Europe, to make the aliyah?”

Daniel Polisar:

I would draw a distinction between what Herzl sought to do and what he ended up doing in practice. He was actually very much against what he called infiltration, that is to say, premature immigration to Palestine, because he was concerned that the more Jews who came in, the more likely it was that the Ottoman empire was going to clamp down on any kind of Jewish immigration. They would shut the door on the prospects of a Jewish state. And in that sense, Aaron was right that, for Herzl, the key was diplomacy. First you get legitimacy for moving into the Land of Israel, and only then do you start actually moving people in. Thus Herzl was pretty much against aliyah, and to the extent he supported it, it was largely as a compromise with the foot soldiers of Ḥovevei Tsiyon.

But here’s the irony of history. It was, to a very large extent, Herzl who inspired the Jews to move to Israel in the Second and the Third Aliyah. If you read stories about people like Ben-Gurion—who moved to Israel in 1906, a few years after the start of the Second Aliyah—and many others as well, going to Palestine was a response to Herzl’s premature death in 1904. The attitude was, “the great leader has passed on; now we have to continue his legacy.” But they don’t carry on that legacy by staying in Europe and writing books. They did it by moving to Palestine and draining the swamps. So, ironically, the man who was against that kind of immigration inspired it because he told the Jews what they knew in their hearts, which was that they were a people, one people; that they could recreate the generation of the Maccabees. And they said, “You know what? He’s right. Let’s do it.” They just didn’t want to wait as long as Herzl would’ve waited for it.

Jonathan Silver:

Sandra Kessler asks, “Where does Jabotinsky, someone whose name we’ve mentioned, fit into the legacy of the figures that we’ve been discussing?”

Daniel Polisar:

I’ll take a crack at this without any pretense to expertise. If you had been able to get Jabotinsky to join this panel and you asked him, “Whom do you see yourself following in terms of ideas?,” you would find that Jabotinsky was more Herzlian than Herzl. He’d met Herzl very briefly, and Jabotinsky writes about it. Herzl more or less was dismissive of this young unknown. But Jabotinsky always believed that diplomacy was the absolute key, and believed that Herzl was the man who had discovered it. It’s true Jabotinsky believed in self-defense, but he thought that Herzl did as well, I think correctly. So I would identify him very much as someone influenced deeply by Herzl.

Jonathan Silver:

Einat, David Schimmel asks a question, following up on your remarks: “Why was it that not a lot of meaningful participation came from Jews of Arab lands in the Zionist movement in these years?”

Einat Wilf:

There are a lot of people who try to assert that Zionism is a 3,000-year-old movement. This is the kind of argument you sometimes see on Twitter. But it’s not true. It’s a modern movement. And yes, one of the factors that gives rise to Zionism is the ancient longing for Zion. But Zionism is also very much a reaction to a sense of disillusionment with emancipation. The whole idea of emancipation and its failure is a key source of Zionism. And the third, of course, is the transition from empires to nation states, which positions Zionism clearly as a modern movement and one that has its initial beginnings in Europe.

If Zionism were only about the ancient longing for Zion, there was nothing preventing Jews of the Ottoman empire, who had lived there for centuries, from immigrating to the land of Israel. But they didn’t do that because they had not yet experienced the promise of emancipation and then the subsequent betrayal. You will begin to have some of that later among Middle Eastern Jews, maybe in Iraq in the 40s and 50s.

But at this point, you don’t have the entire story of emancipation and its failure. And because of the way that World War I ended, the transition from empire to nation states in the Middle East did not happen in the way that it happened in Europe where the Czechs and the Slovaks and the Ukrainians and the Poles are all bubbling for years with a desire to organize themselves and to replace the empire with independent states. In the former Ottoman territories, the victorious French and British, making a kind of compromise with the Americans, draw lines to create new states, and essentially declare that they’ve granted self-determination, but not in the way the Arabs wanted it—and not completely in the way that the Jews wanted it either.

I always like to bring the example of the Turks, the Kurds, and the Armenians. This was a great example, by the way, of what could have happened. This could have been the fate of the Jews. There was supposed to be an Armenia and there was supposed to be a Kurdistan as part of the partition of the Ottoman empire. The Turks did what they did to the Kurds, to Armenians, and that tore apart the San Remo agreements and that’s it. And Turkey emerged twice as large as it was supposed to be according to the international treaties, and nobody says anything. This could have been the fate of the Jews. They could have lost their shot at independence much as the Kurds did. They didn’t; thanks, in part, to a combination of facts on the ground. And that episode really shows that international recognition is not enough.

I once gave a talk for the Balfour Declaration here, and the title of the talk was, “Thank You Lord Balfour, We’ll Take It from Here.” The Palestinians, and so many other people, put so much emphasis on the Balfour Declaration. But read it. It’s nothing. It states that “His Majesty’s Government view with favor” the creation of a “Jewish national home.” There’s not much substance there. The thing that matters really is the mandates, the League of Nations, and really what the Jews ultimately did. But again, unfortunately, not in time. And the Jews of the Arab and Islamic world unfortunately really only woke up when the Arab world made anti-Zionism into its central organizing principle, and made it clear that as long as Jews consider themselves the equals of Arabs and Muslims, they can’t stay.

Jonathan Silver:

Aaron, here’s a last question to you from the audience. This questioner asks, “To what extent, if any, did Pinsker link emancipation with the cultural and social development of the Jewish people?” And here, I would just add that you could unpack the image of the Jews as a “ghostly” presence that you began your remarks with, and through which Pinsker describes the condition of the Jews in Europe.

Aaron Schimmel:

I think the use of the phrase “Jewish people” in the question is loaded because the emancipationist approach places the focus on individuals, who are supposed to integrate and become educated in the language of the country they live in. And that vision is absolutely linked to cultural and social development, because its message is to leave the Talmud behind and to get in touch with and learn about secular culture, and to be involved in that culture. And this, of course, leads to social change because in Russia, in this time, a certain level of secular education is required to go to university, to have any access to a whole variety of careers that are in the medical field or in the legal field, and by pursuing such careers Jews can change their role in society.

In Pinsker’s Auto-Emancipation, he suggests that there will be major social changes for Jews that continue to live outside of this Jewish state. But unlike future Zionists, Pinsker doesn’t talk about culture. At least in his writings, he is not a huge champion of the Hebrew language. His vision is very political. For him, the creation of a Jewish state is a way to put the Jews on the world map politically, but it would take other Zionists to talk about the cultural development of the Jewish people in a meaningful way.

Jonathan Silver:

Einat, Dan, Aaron, I want to ask the final question myself, which has to do with one of the reasons that we at Mosaic, in particular, were interested in featuring Pinsker. When we look around at so many of the institutions in the West, we are seeing institutional failure and the evaporation of confidence in the forms and institutions of our common public life. And there’s a sense in which it’s a time to build. This is a time for Jewish builders, and Pinsker is a Jewish builder. And thinking about the boldness of Pinsker’s imagination at that time makes me want to ask you what we need to build now. And if we were to channel Pinsker, what he might provoke us to take a look at.

Einat Wilf:

Sometime when I talk about Jews, especially young Jews, who are anti-Zionist, I compare them to wealthy heirs who say that money isn’t important. We live on the benefits of the tremendous institution-builders and visionaries. Given that we want to stay in the Land of Israel, and that we want to make sure that our third sovereignty thrives there, the big challenge is getting the Arab world and the Muslim world to accept us and to embrace us as equals, equal claimants, equal people. And I think the implications for Israeli society of true Israeli integration into the Arab world could be tremendous.

Daniel Polisar:

I would say that Pinsker, although he wasn’t such a big builder himself, is a phenomenal example to builders because, first of all, he’s a leader who didn’t want to be a leader but who knew he was the right person in the right time. For Herzl, the opportunity to lead the Jewish people was something he had been waiting for, whether for the Jews or for some other group. He leaped on it. Pinsker did it out of a genuine sense that this is something that’s absolutely essential, that “I’m the right person because I wrote a book and it resonated, and I have a certain credibility.” But a part of building is for people who don’t necessarily want to lead to recognize that they have to step up and do what the moment requires in a selfless way. For me, that’s the first and maybe the key takeaway away from Pinsker.

But the second thing is that, although he writes beautifully, his basic message is very simple. What we all need to do is step up. Regardless of what we think, we need to look reality in the eye. And so a Pinsker of today, I think, would say we need more aliyah and more defense of what the state of Israel does, and a strong army. He would just look at nuts and bolts—Where are we? Where do we need to get to?— without an unnecessary, and often damaging, sophistication. And he would be like a good Israeli army officer, who says, “Come after me.” He would lead in that kind of effort. And I think in that sense, Aaron gets enormous credit for having put on the map exactly the right kind of leader for us to be learning from today.

Jonathan Silver:

Aaron, we’ll give you the last word.

Aaron Schimmel:

I want to return to the idea of looking reality in the eye. One of the things that’s most striking to me about Auto-Emancipation is Pinsker’s diagnosis of anti-Semitism as something that’s not going away. And for American Jews, anti-Semitism is not always something that’s a feature of life, and it’s easy to forget that it’s there and needs to be taken seriously. And I think as we’ve seen that with the ADL lately showing disinterest in anti-Semitism, and focusing on “all forms of hatred” and whatever other taglines that they use. Thank God anti-Semitism is not the problem, in America, that it was in Russia. But it’s still there. It’s something that Jews are experiencing in the U.S., and I think it’s something to be taken more seriously.

More about: Israel & Zionism, Leon PInsker, Mosaic Video Events, Theodor Herzl