In his Mosaic essay “The Restoration of the Jewish People,” Ofir Haivry has concisely summarized the range of wholly Jewish, partly Jewish, marginally Jewish, and newly Jewish existence in our contemporary world. The picture he paints is one of a bewildering variety, although to say that it is “unprecedented in Jewish history, . . . certainly at any time since the destruction of the Temple some 2,000 years ago” is pushing things a bit too far back in time.

Actually, it was during the several centuries after the Temple’s destruction that Jewish life in antiquity was at its most wildly pluralistic. This pluralism was ended by the rise to complete dominance of a rabbinically regulated halakhic Judaism—and it was the waning of this dominance in modern times that made room for the proliferating expressions of Jewishness that we encounter today.

Haivry and the committee of the Israeli Ministry for Diaspora Affairs chaired by him have posed the sensible question: what are we (that is, we Jews both singly and collectively) to do about these expressions of Jewishness—and, especially, about those involving non-Jews with rediscovered Jewish roots or with newfound feelings of affinity for Judaism and/or the Jewish people?

Haivry and the ministry’s recommendations are sensible, too. They suggest that we encourage such individuals, welcome them into Jewish life when and as best we can, and provide them with the educational materials and assistance needed to strengthen their feelings of Jewishness. And why, really, shouldn’t we?

I suppose we should. Still, I believe there are some things we need to ask ourselves.

The first is why we should want non-Jews to draw closer to Judaism or to the Jewish people. Is it because we believe that Judaism is a superior religion and therefore better for them than other forms of faith or non-faith? Because their need to affiliate with the Jewish people is so great that it would be cruel to deny it? Because we want there to be more Jews in a world in which Jews are a tiny minority? Because we think that if there are more Jews, there will be greater support for Israel and other Jewish causes?

In short, what are our motives? How disinterested or, contrarily, how driven by self-interest are they? How disinterested or driven by self-interest should they be?

The second set of questions relates to the first. Even if we are convinced that Judaism is the best of religions, we will differ about what form of it is best; even if we assume that more Jews are good for Israel and the Jewish people, we will argue about what Israel and the Jewish people’s good consists of.

How can Jews agree on coherent policies toward non-Jews wishing to join or be associated with them if they cannot agree on anything else? How can Israeli governments formulate such policies when, at any given moment, they are made up of coalitions of different forces with clashing opinions about the basics of Jewish identity?

This is not an argument for doing nothing. It is an argument for underlining the phrase “more than one” in Haivry’s call for “the founding and support” of institutions, “preferably more than one,” to investigate and deal with today’s Jewish multifariousness. In such matters, one of anything, whether it is a point of view, an agency, or a government, is an invitation to a politics of inclusion and exclusion with all of the arbitrariness that this implies. Only a plurality of organizations and approaches can successfully cope with a pluralistic reality.

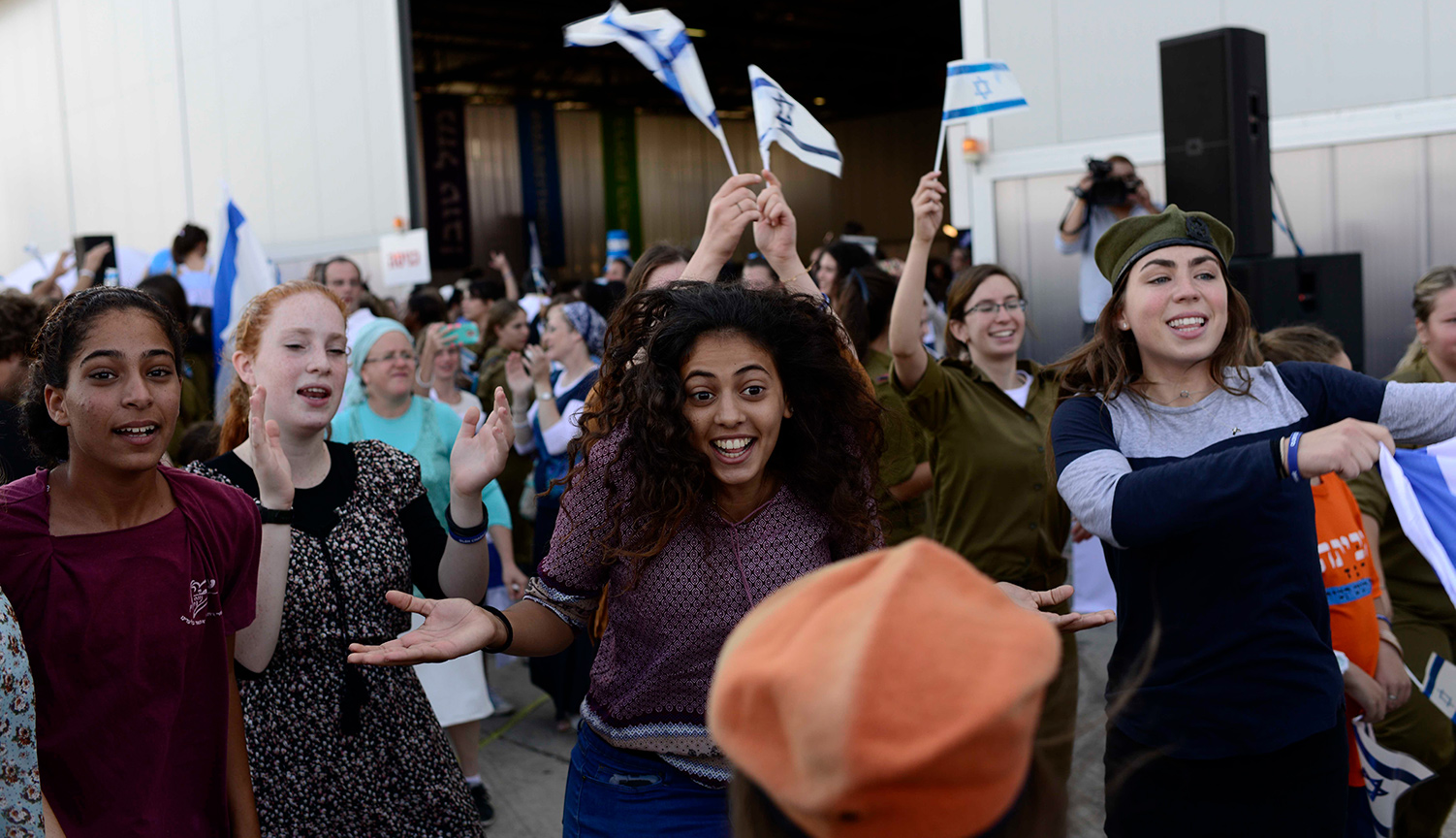

I speak, in a small way, from personal experience. For the past twenty years I have been involved with the B’nei Menashe, the Judaizing group from the northeast Indian states of Mizoram and Manipur whom Haivry mentions and briefly discusses. Nearly 5,000 of them (rather than 3,000, as stated by him) now live in Israel as halakhic converts to Judaism and full citizens. Roughly the same number remain in India, awaiting an aliyah that has been slow in coming. Their story is a remarkable and inspiring one, but it has also been fraught with difficulties, at least some of which might have been avoided had they been provided with more options and dealt with less paternalistically.

I won’t and can’t go into details. I’ll simply observe this: because the entire fate of the B’nei Menashe has been placed, with the approval and backing of the state of Israel, in the hands of a single organization that has been entrusted with the task of bringing them to Israel, of seeing to their conversion, and of deciding where and how they are to live in its aftermath, many mistakes have been made and much abuse of power has taken place—as always happens when monopolies are allowed to function.

Many questions should have been asked that were not. Was it and is it necessary or desirable to encourage all of the B’nei Menashe to come to Israel? Should those who came have been enabled to do so on their own and at their own timing, and to make their own arrangements once they arrived? Should Jewish organizations have fought to make it possible (as it currently is not) for the B’nei Menashe to convert to Judaism in India? Should the institutional groundwork have been laid (as it has not been) for a long-term continuation of Jewish life in India for those who might have preferred to remain there?

I don’t know the answers to these questions. At least some involve deeper issues of Jewish peoplehood, Zionism, and the raisons d’ȇtre of Jewish life that go well beyond the specific case of the B’nei Menashe. I do know that, as glad as I am that thousands of B’nei Menashe are now in Israel, I sometimes wonder uneasily, looking at the many social, economic, and cultural problems of adjustment that they face, whether they are really better-off for it.

Their lives in India were not bad. Most were poor but not impoverished, and they benefited from strong social and family support systems, and from a native rootedness in their environment, that they no longer have. Has their “return” to Judaism (and I personally believe that their claim of an ancient connection to the biblical tribe of Menashe is not unfounded) been an overall plus for them? Has their aliyah?

This is ultimately something that only they can determine. My point is that we who encourage and assist others to cast in their lot with us need to think carefully about what we are doing. Although it’s all very well to be excited by the prospect of millions of new Jews all over the world adding fresh vigor to the Jewish people, each one of these potential millions has a life of his or her own that stands to be changed forever in the process.

Yes, it is his or her life; he or she is primarily responsible for it. But we bear a measure of responsibility for it, too, and this is not to be taken lightly.

More about: Aliyah, Bnei Menashe, The Jewish World