In his stirring essay “The Message from Jerusalem,” Eric Cohen seems to intend two audiences: a Jewish audience and a Christian audience. The better to appreciate how the essay speaks to each audience, let me first try to identify the kind of Jews most likely to agree with Cohen and, conversely, the kind most likely to disagree, and similarly the kind of Christians most likely to agree and to disagree.

On theological-political issues—i.e., issues of faith and, especially, the place of faith in the public square—Jews likely to agree with Cohen have more in common with likeminded Christians than they do with unlikeminded fellow Jews; and the same is true on the Christian side, where, on these same issues, likeminded Christians have more in common with likeminded Jews than with unlikeminded fellow Christians.

This is emphatically not to say that such cross-religious agreement among the likeminded is apt to result in a giant leap into a syncretistic interfaith merger—for, as Cohen well puts it, “ultimate theological differences between Jews and Christians will never be resolved” (to which I’m tempted to add, “at least not in this world”). But I hope this little anatomy of Cohen’s intended readers will enable both friend and foe to recognize themselves more readily.

To illustrate concretely what I mean by the divergent theological-political stance of the two kinds of Jews and Christians, let me recall an almost two-decades-old incident that can also function as a template for analyzing Cohen’s essay.

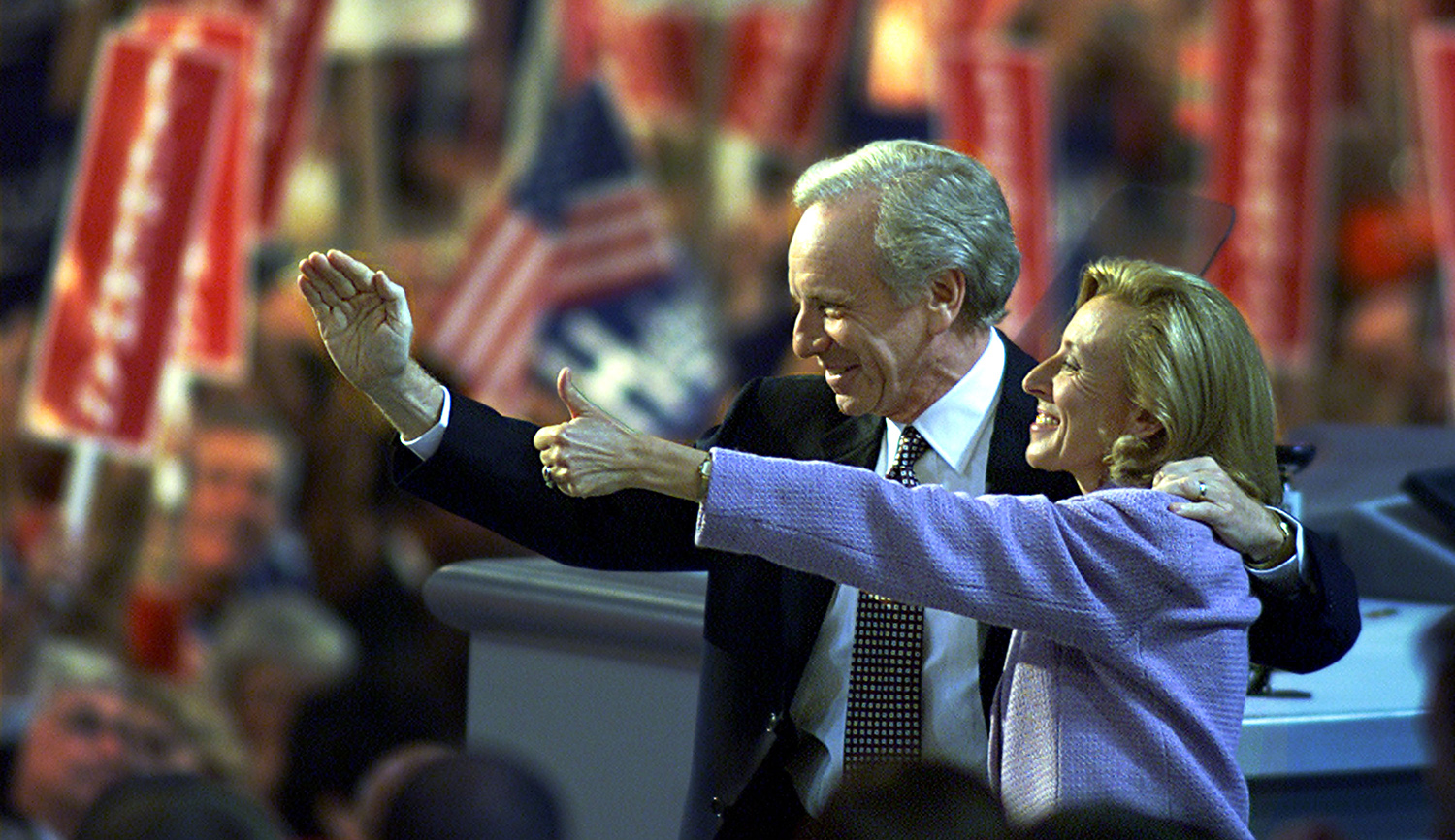

In 2000, the Democrats nominated Senator Joseph Lieberman as their candidate for vice-president of the United States. Not only was Lieberman the first Jew to be nominated for this high office by a major political party but, even more amazingly, he was and is an Orthodox Jew.

As such a Jew, Lieberman is a strict observer of the Jewish Sabbath (in Hebrew, a shomer shabbat). True to his religious convictions, he announced at the very outset of his appointment as Al Gore’s running mate that he would not campaign on the Sabbath.

What was the response of Jews? What was the response of Christians? Having been, at this time, a fellow member with Lieberman of the same Orthodox synagogue in Washington, DC, I was well aware that his religious convictions took precedence over his political ambition. Nor was I in the least surprised when he announced those convictions publicly—in an act that perfectly typifies what Eric Cohen means in writing of the Jews as having been “chosen to play a special role as a light unto the nations.”

To his fellow Jews, first and foremost, Lieberman’s statement proclaimed that politics is not an end in itself and that the duty to obey God’s commandments takes precedence. Indeed, the recognition of this priority enables Jews to be better American citizens, even better office-holders, for it signals an understanding that our country is founded not only on God-given rights (as Jefferson put it in the Declaration of Independence) but even more so on God-given duties.

Zionism also comes into the picture. American Jews like Joseph Lieberman worship in synagogues where the prayer for the state of Israel is recited with the same fervor as the canonical prayers of the traditional liturgy. Such public fidelity to the Jewish state is at one with public fidelity to the Jewish people, to its Torah, and to the Lord God of Israel. For such Jews, our Zionism is rooted and inseparable from our Judaism.

At the time, however, many other Jews, mainly liberals, were embarrassed both by Lieberman’s words and by the public nature of his religious conduct. In fact, the head of one major American Jewish organization publicly bemoaned the senator’s “injecting religion” into what was supposed to be the purely secular political process of a presidential campaign.

To me, this response amounted to nothing less than what Jewish tradition calls a ḥillul ha-shem, a desecration of God’s Name. For a prominent Jew to question the motives of an even more prominent Jew who publicly observes the Torah’s commandment to “keep the Sabbath day” evinces at the very least a deep-seated embarrassment with one’s own tradition, if not a contempt for it.

Indeed, this same discomfort with the public observance of Judaism may help explain why, today, more and more non-traditionalist American Jews and their leaders are also becoming less and less attached to Israel and to Zionism. One factor here may be that Israel itself, an explicitly secular—that is, non-theocratic—state, has become more traditionally Jewish in both its official and its popular presentation. In the meantime, almost all immigration (aliyah) from America to Israel is drawn from the ranks of traditionally religious Jews, many of whom have become turned off by the outspokenly secular stance of the “old-guard” communal leadership.

As for the Christian response to Lieberman’s announcement, I personally knew Christians (both Protestant-evangelical and Catholic) who regarded his Sabbath observance as, in brief, the opposite of a ḥillul ha-shem: namely, a sanctification of the divine Name (kiddush ha-shem). As one Christian friend put it to me (paraphrasing Matthew 22:21), “Senator Lieberman is rendering unto God what is God’s, and only thereafter rendering unto Caesar what is Caesar’s.” In fact, a number of such Christians of my acquaintance who normally would never have voted for any Democrat changed their vote in 2000 precisely out of admiration for Lieberman’s sincere and consistent religious observance. They recognized, as Cohen puts it, “God’s election of the Jews [to demonstrate] the biblical vision of human life as sanctified normalcy under commandment.”

Moreover, just as such Christian support for an Orthodox Sabbath observer owed much to the fealty paid by these traditional Christians to the Hebrew Bible, the same devotion to the same source explains as well the theological gravitas of Christian support for the state of Israel as the true and rightful homeland of the Jewish people. The Bible teaches that God promised the land of Israel to the people of Israel (known, ever since the expulsion of 586 BCE, as the Jews): a promise made to them not as passive recipients but in enablement of their ordained mission to “possess it and settle it” (Numbers 33:53).

In other words, the same divine mandate that the Sabbath be kept by the Jews similarly mandates that the land of Israel be possessed, settled, and defended by the Jewish people in the most politically, economically, and militarily effective ways—and always according to the Torah’s standard of justice.

The only Christian I know personally who objected to Lieberman’s public Sabbath observance was a liberal Protestant academic colleague of mine who, like his similarly-minded Jewish compatriots, feared Lieberman’s injection of “religion” into the secular procedures of American political life. Not at all atypically, this mainline Protestant was also (to put it mildly) not a friend of the state of Israel, and is still of the same mind today. He agonizes that Israel is becoming a Jewish “theocracy” at the expense of its Christian and Muslim citizens. And he is intimidated by Protestant evangelicals (whose ranks are swelling while his own are shrinking) and offended by their enthusiastic support for the Jewish state and their sympathy with its growing public religiosity. Once again, the old condemnation of Jewish “particularism,” of Jewish “clannishness,” is being reasserted in the form of overt anti-Zionism, both by some Gentiles and even by some Jews.

As one who would surely deny that the Bible’s commandments are divinely revealed, and who, when pressed, would just as surely denounce them as “harsh and archaic laws that restrict human freedom” (in Cohen’s paraphrase of this widely held position), my liberal colleague is at least being consistent in his opposition to Israel’s genuine Jewish culture. Nevertheless, it has long been held that faulty premises lead to faulty conclusions, no matter how impeccable the logic in-between. The faulty premise here is that Christianity and Judaism can somehow survive, let alone flourish, without a commitment to divine revelation and its particularistic normative demands.

The truth is otherwise. Once faithful Jews and faithful Christians submit their faith to the greater authority of any secularist “universalism,” becoming not only in the world but of it, they will sooner or later be done-in by that world.

Eric Cohen’s essay will no doubt find favor in the eyes of the kinds of Jews and the kinds of Christians who will readily agree with it. As for those who will readily disagree with it, let me suggest (if any of them are listening) that they respond to its challenge with answers of their own. In so doing, they will also benefit from his trenchant critique of their positions.

More about: Interfaith dialogue, Politics & Current Affairs, Progressivism