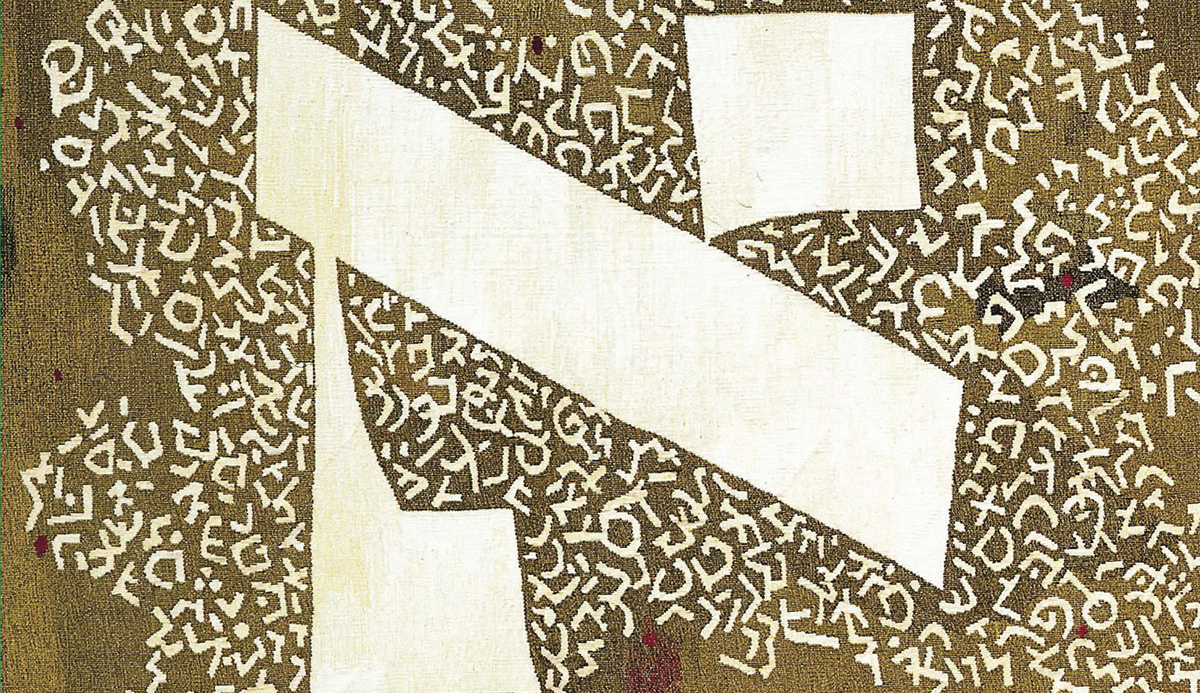

From the cover of Robert Alter’s translation of the Hebrew Bible.

In his elegant review of Robert Alter’s English-language version of the Hebrew Bible, and in his extensive interactions with Alter’s word choices, Hillel Halkin has provided Mosaic readers with invaluable access to this new and important literary achievement. While generally appreciative of Alter’s guiding principles—with the exception of a significant caveat at the very end of his essay—Halkin’s word-by-word analysis of some of Alter’s renderings demonstrates that, even by the translator’s self-imposed standards, there is room for improvement.

Early on in his essay, Halkin introduces, as points of comparison, a half-dozen other English-language versions by single authors ranging in time from the mid-19th century to a decade or so ago. For the most part, however, these translations are little more than singular oddities that add little if anything to our appreciation and assessment of Alter’s work.

In my view, it would have been more productive to compare Alter with other Jewish Bible translators. In this connection, I’m puzzled that Halkin omits any reference to Isaac Leeser, whose 19th-century version, The Twenty-Four Books of the Holy Scriptures, was his alone and, to boot, the first English-language version of the Bible produced specifically for American Jews.

Leeser’s work, although sometimes disparaged and little-known today, was very influential in its time, serving as the Bible for Jewish Americans from the 1850s to 1917, when the Jewish Publication Society (JPS) issued its Holy Scriptures According to the Masoretic Text in English. Additionally, Halkin might have brought in other, more recent Jews who have worked in English on their own versions of parts of the Hebrew Bible, notably Everett Fox, Richard Elliott Friedman, and Aryeh Kaplan.

But is Alter’s version indeed “Jewish” in some definable sense? Reviewers, including Adam Kirsch, have striven to argue as much, and the very fact that the work has been prominently featured in Mosaic in addition to Tablet and the Jewish Review of Books would appear to support the idea of an inherent connection between Alter’s version and, in a word, Judaism—aside from the fact that Alter not only is Jewish himself but has also written widely on modern Hebrew literature in addition to biblical prose and poetry.

One reason we might hesitate to call Alter’s version in any way Jewish is that he, conspicuously, does not do so—either in his title, his various introductions, his notes, or his commentary. Nonetheless, Jewish it is. This may become clearer if we look at it from the outside, as it were—and in particular at the criticisms leveled by John Updike at Alter’s translation of the Torah, The Five Books of Moses, published separately in 2004. Writing in the New Yorker, Updike bemoaned what he saw as “the sheer amount of accompanying commentary” on almost every page of Alter’s translation, and deprecated this tendency as “an overload of elucidation imposed on the basic text” [emphasis added].

In using the phrase I’ve italicized, Updike, I believe, was being disingenuous at best, prejudiced at worst. As a Protestant, he was entitled to like his versions of the Bible commentary-free. But he had no literary or theological ground on which to impose his strictures on Alter, who in this respect happened to be perpetuating a longstanding Jewish exegetical tradition.

Hillel Halkin is not alone among reviewers in paying little or no attention to the quantity and quality of Alter’s extensive commentary—although it is highlighted in the subtitle of the book: “A Translation with Commentary.” (See also Richard Elliott Friedman, Commentary on the Torah with a New English Translation.) After all, it is a frequent characteristic of Jewish versions of the Bible that the commentary is at least as important as the biblical text itself.

Among Jewish translations that we can adduce in this connection, all of which have some form of the term “commentary” in their titles, are those by Saadiah Gaon (Tafsir, Arabic, 10th century), Moses Mendelssohn (Biur, German, 18th century), Samuel David Luzzatto (Translation and Commentary on the Pentateuch, Italian, 19th century), and Samson Raphael Hirsch (Commentary on the Torah, German, 19th century).

Indeed, designating Alter’s version as Jewish allows for enhanced comparisons in many other directions as well. Take, for example, Alter’s interest in reproducing in English the specifically literary qualities of biblical Hebrew. The same interest was at work in the 1917 JPS Bible, which was a Jewish and American revision of the British Revised Version of 1885, itself based on the King James Version (KJV, 1611). JPS’s editor-in-chief Max Margolis had enthusiastically endorsed this procedure. As an immigrant from Eastern Europe, he strongly urged his fellow immigrants to learn their English not from what they read in the daily paper, and certainly not from what they heard on the street. The best writers in English, Margolis wrote, had based themselves on KJV, and JPS should follow their lead.

Why was this especially meaningful in a Jewish version? Because, as Margolis saw it, KJV “has an inimitable style and rhythm; the coloring of the original is not obliterated. . . . What imparts to the English Bible its beauty, aye, its simplicity, comes from the [Hebrew] original.”

This literary emphasis, if you will, is typically more characteristic of literal translations, which scholars describe as employing the method of “formal equivalence.” Such versions, as is the case to an extent with Alter’s, require that the reader expend considerable energy to comprehend the meaning of the text—a move that makes sense when we consider that biblical Hebrew is separated from us by chasms of time, place, and culture.

True, some influential Jewish versions have instead employed the freer approach now designated as “functional equivalence,” whereby translators seek to put into contemporary English what they understand the original authors wanted to convey to those who heard or read their words in antiquity. For this reason, we cannot say, on the basis of style alone, that one approach to translation is more authentically “Jewish” than others.

And here I should pause to add a further point: Alter and his cheering supporters are hardly reluctant to criticize as failures those whose translations reflect goals other than his. For his own critical arrows, the 1985 version of the JPS Bible (Tanakh: The Holy Scriptures) seems to serve as something of a bull’s-eye. Even Everett Fox, who is closest to Alter in many ways, is not immune to attack. While Alter’s obvious passion in defense of his work is (I suppose) understandable, this rush to evaluate is unfortunate.

For myself, I prefer to be descriptive, basing whatever evaluations I may make on the goals that translators set for themselves. Alter’s literary emphases are laudable, and he should be judged in accordance with them—which is basically what Halkin does. But by that standard, Saadiah Gaon’s Arabic work, which is decidedly a functional rather than a formal equivalent, is no less deserving of our approbation—and our criticism—as is also JPS 1985.

Finally, where else in contemporary culture can we find something, or someone, widely recognized as Jewish in the absence of most of the traditional markers of Judaism? Answering this query naturally led me on a direct path to Seinfeld. Alter as Seinfeld? Seinfeld as Alter? Maybe not so far-fetched as it seems at first glance. But if we are to give Alter his due (Seinfeld and others have received theirs in abundance), we must be at least as industrious and as reflective as he has been. He deserves nothing less.