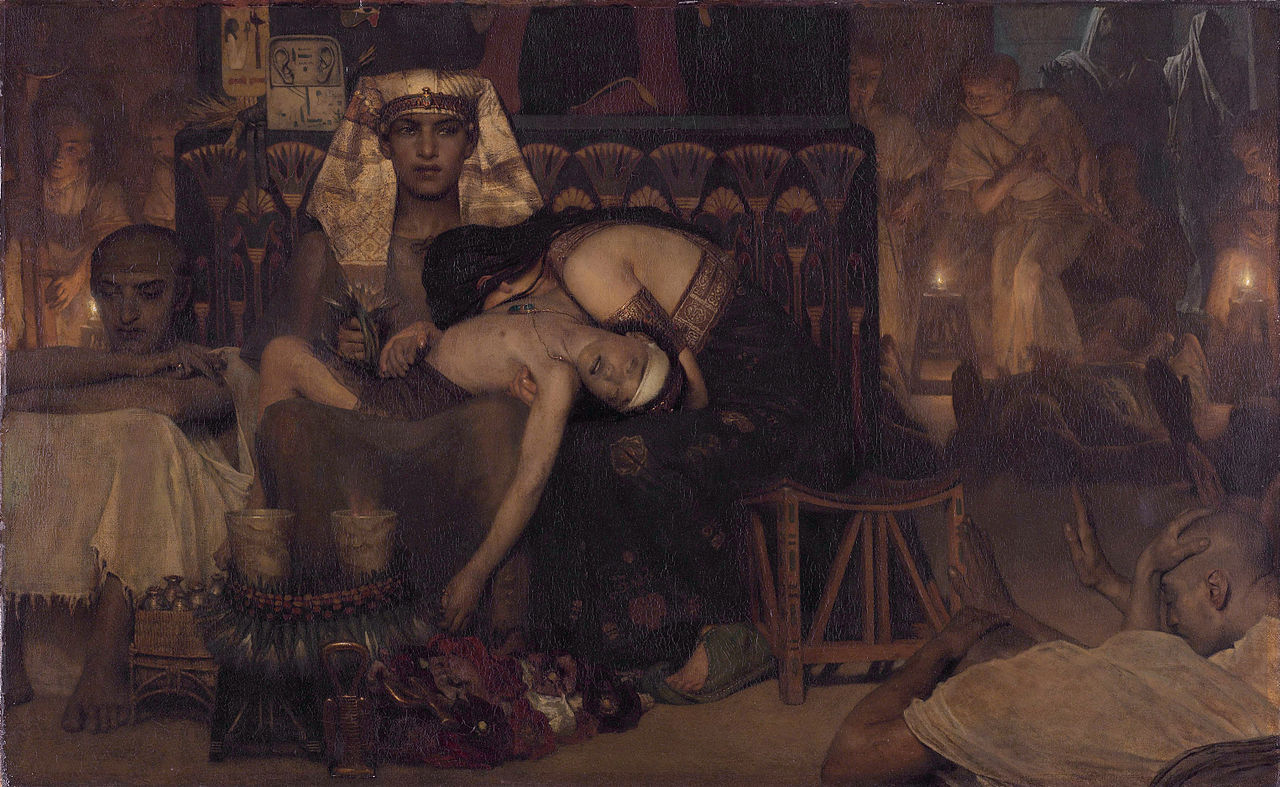

From Death of the Pharaoh’s Firstborn Son by Lawrence Alma-Tadema, 1872. Wikimedia.

In his essay “The People-Forming Passover,” Leon Kass has once again given us a probing reading of the Hebrew Bible, approaching the text with an openness to discovery, fostered by the fundamental questions that guide his inquiry. Here, as elsewhere, his perceptive attention to detail prompts us to think through issues of nature and law, politics and theology, the realm of the human and the divine. We see how and why The Beginning of Wisdom, Kass’s inspiring study of Genesis, has led to Founding God’s Nation, his eagerly awaited study of Exodus from which his essay in Mosaic has been drawn. As Kass argues here, focusing on chapter 12 and the early sections of chapter 13 in Exodus, the Passover ordinance represents the first national law of the Israelites: a definitively new political-cultural development, significantly beyond the parameters of the extended family that was the main subject of Genesis.

In dialogue with Kass and in the spirit of his reading, I offer some thoughts about the meaning of the “Lord’s Passover” as it unfolds in Exodus 12, and in particular, the consequences drawn from it at the opening of chapter 13.

Exodus 12 is set on the night before the departure of the children of Israel from Egypt after four centuries of bondage. At dusk on that fateful night, God instructs Moses that each Israelite household is to slaughter a sacrificial lamb and mark with its blood the side-posts and lintels of the house, thereby signaling a dwelling to be spared when the Lord passes through the land to smite all the firstborn of the Egyptians. The Israelites are to eat the roasted meat of the lamb together with unleavened bread and bitter herbs, their shoes on their feet and staff in hand, ready to depart in the morning.

At this dramatic moment, the driving rhythm of the plot comes abruptly to a halt and we hear, in God’s voice, His plan for an everlasting memorial: every year, on the fourteenth day of what is now designated as the first month of the calendar year, all leavened products must be put away for seven days. The unleavened bread of affliction has become the bread of freedom.

Moses, in then duly reporting this plan of God’s to the Hebrew elders, enlarges and humanizes it. The future “service” (avodah) of Israel to the Lord will at once memorialize and replace the labor (avodah) performed till now by Israel for Pharaoh. It will inevitably move the young to ask, “What does this mean?” And the proper response is to tell them the story of the Lord’s Passover. Moses infuses that story and its prescribed rituals with an educational motif, to be etched into the Jewish collective memory from generation to generation: the image of ancestors saved from “the destroyer” (12:23) amid the frightful urgency of the night on which they prepare to leave the only “home,” such as it was, that they had known for centuries.

Reading about that night of terrible dread, who cannot be reminded of its innumerable recurrences in the life of the Jewish people ever since?

The story peaks at midnight as God initiates the tenth plague, smiting the firstborn of Egypt, human and beast alike. In a bookend phrase recalling the cry of pain that went up to God from His oppressed and afflicted people (3:7), another “great cry” now resounds through the land (12:30). Pharaoh, obdurate over the course of nine preceding plagues, but now desperate, summons Moses and Aaron and commands them to leave. With their unleavened dough, and the spoils they have acquired from the desperate Egyptians, a “mixed multitude”—600,000 men on foot with families—set out on an unknown journey through the wilderness.

“For such a momentous event,” Kass comments, the text’s tersely prosaic description of the departure from Egypt “is almost anticlimactic.” Here once again the narrative of deliverance stops in its tracks to resume God’s instructions for the future “night of watching unto the Lord for all the children of Israel throughout their generations” (12:42). But now, in reiterating to Moses and Aaron the ordinance for the Passover sacrifice and meal, God adds a comment on who besides the Israelites can partake of it: no to foreign aliens, but yes to household servants and “sojourning” strangers, as long as the males are circumcised.

Kass marvels at the remarkable inclusivity expressed here, the lack of discrimination against outsiders: a people is being forged on the basis of a new principle of identity, with one law for the native and stranger alike. Yes, but: incorporating the Abrahamic covenant into the imminent Mosaic covenant requires the original obligation of circumcision, which is hardly trivial. And on this point we may pause.

The call for circumcision at the end of chapter 12 resonates eerily with a passage in chapter 4 where the larger narrative of Israel’s eventual redemption from Egypt has its beginning. After their exchange at the burning bush, God conveys to Moses the words that he is to speak to Pharaoh as he plays the part of God’s spokesman: “Israel is My son, My firstborn.” Should Pharaoh refuse the demand to release the Israelites from bondage, then “I will slay thy firstborn son” (4:23, emphasis added).

This adumbration of the tenth and final plague is followed immediately by one of the most mysterious passages in the Hebrew Bible. After his encounter with God, Moses is on his way back to Egypt with his family when suddenly, in the dark of the night, “the Lord sought to kill him.” Thereupon his wife Zipporah takes a flint, circumcises their son, and “touches” his feet with the words, “Surely a bridegroom of blood art thou to me” (4:25).

Does some chain of association link this blood of circumcision with the blood of the sacrificial lamb with which the Israelites will “touch” their doors and thereby save themselves from the slaying of the firstborn (12:22)? And would that association not imply another association, even darker, more complicated, and more puzzling?

That puzzle unfolds at the opening of chapter 13 in what Kass calls an “appendix” to chapter 12. Here a new directive is addressed by God to Moses: “Sanctify (kadesh) unto Me all the firstborn, whatsoever openeth the womb among the children of Israel, both of man and of beast, it is Mine” (13:1-2).

This terse divine order, explicitly making no differentiation of human from beast, also remains silent on what is involved in “sanctifying.” Clarity comes only with Moses’ interpretation as he relays it to the people. When they arrive in the promised land, he says, they are to “set apart unto the Lord all that openeth the womb.” Children will once again ask what this practice means and they are to be told: “as the Lord slew all the firstborn of the Egyptians, . . . therefore I sacrifice to the Lord the male firstborn of a [clean animal], but the firstborn of my sons I redeem” (13:11-14, emphasis added).

The Hebrew verb for “redeem” used here, padah, has its basis in social legislation, where, according to David Daube, the late scholar of biblical, talmudic, and Roman law, it involves the ransom of a person, or an animal, from a fate that otherwise threatens. Daube contrasts it with ga’al, which implies recovering a person or thing once belonging to you but lost or taken—as in God’s promise (for example in Exodus 6:5) to recover the children of Israel.

God’s slaying of the Egyptian firstborn might have been readily understood as a “measure-for-measure” response to the sentence of death pronounced by Pharaoh upon all male infants of the Hebrew slaves. But that is not the context in which the Bible frames it. Instead, the slaying of the Egyptian firstborn is explicitly introduced as punishment for Pharaoh’s refusal to release Israel, God’s own “firstborn” (4:22). But now that collective firstborn has itself been replaced, as it were, by the firstborn son in every family, whose “redemption” from this condition involves, in turn, a multi-layered network of still other associations.

Most directly, the blood of the sacrificial lamb, already linked with the blood of circumcision, serves on the night of the tenth plague to avert the sacrifice of the Israelites’ firstborn. This is a reminder, as Kass alerts us, of the Binding of Isaac: in the requirement to redeem his firstborn son, every father faces symbolically the dreadful demand issued to Abraham and only at the last minute rescinded. As the biblical text proceeds, moreover, the setting-apart of the firstborn son of every family is interpreted as consecrating him for service to God, which is in turn replaced by the selection of one of the twelve tribes for an exclusive sacred duty: “I have taken the Levites from among the children of Israel,” God declares, “instead of every firstborn that openeth the womb; . . . and the Levites shall be Mine; for all the firstborn are Mine” (Numbers 3:11).

In this last passage, the immediate context has to do with the establishment of Aaron’s hereditary priesthood. But God again makes explicit the connection with Passover, and generalizes: “On the day that I smote all the firstborn in the land of Egypt I hallowed unto Me all the firstborn in Israel, both man and beast, Mine they shall be: I am the Lord” (3:13). God’s saving of the Israelite firstborn from the fate of the Egyptians comes with a “sanctification” that makes all of them His special possession.

Indeed, the idea of God’s ownership of the life that “opens the womb” can be traced all the way back in the Bible to the primordial firstborn. In the first words spoken outside the Garden of Eden, Eve gives birth to Cain, her firstborn, with the proclamation, “I have gotten me a man with the Lord” (4:2).

Until then, new human life has been solely in the hands of God; now it comes through nature, with a conspicuous role for the mother. But Eve—so named for her role as “mother of all living”—utters what sounds ominously like a boast, and in the prolonged family drama of Genesis, each generation of women who follow Eve experience the consequence of that boast. The “chosen” son is born in every case to a mother previously barren, and is thus the issue not of natural reproduction but of a miracle. That son, moreover, is never the firstborn—which flies in the face of the customary human principle of primogeniture.

In his essay, Kass stresses the biblical rejection of that principle. From the perspective of what he terms “God’s new way” for the Jewish people, the cardinal mistake of primogeniture lies in the taking of one’s direction from nature—in this case, from the natural birth order. The conventional assignment of the family birthright to the firstborn comes under criticism in all of the family stories in Genesis, where it is counterposed to a different standard altogether. In every generation, God’s choice falls instead on the individual who proves to be right for the preservation and the promise of the Abrahamic heritage.

Here, as throughout Kass’s biblical studies, one—perhaps the—central concern is the presence of dangerous impulses in the human psyche that make it necessary for our natural selves to be shaped by moral instruction and God-given law. That kind of danger is exemplified by the status of the firstborn son, who represents at once an extension of the father’s strength and a threat to the father’s power. The biblical corrective is the conception of the firstborn as one who belongs first and foremost to God, as Kass writes, “not to nature or our prideful selves.” But I ask: is it really possible, or desirable, simply to deny, let alone surrender, this most intense attachment to one’s own?

The threat of the son to the father’s power, which shows up at the extreme in the crime of patricide, is the core of the Oedipal plot that is dominant in Greek thought, from Hesiod’s primordial gods to Plato’s account of the tyrant. Perhaps surprisingly, this impulse seems to be almost entirely absent from the Hebrew Bible, where the family drama, from the episode of Cain and Abel onward, is dominated instead by the threat of fratricide. This striking difference between Athens and Jerusalem is deserving of further reflection.

The crime of patricide in the Oedipal plot is connected with the danger of infanticide, in the form of a preemptive strike by the father fearful of being usurped by his son. The Hebrew Bible provides its own profound meditation on child sacrifice, the paradigmatic case being the Binding of Isaac. To Kass, that fearsome episode conveys the Bible’s absolute rejection of human sacrifice. It does so, of course, even while depicting Abraham’s wholehearted obedience to the divine command to offer up his son. But could Abraham’s response to God’s test thus be seen as a failure? After all, God sends only a “messenger” to stop him from the fatal deed, and after this event He never comes to Abraham again. Could the episode be meant to convey not only the rejection of human sacrifice but a critique of the very willingness to give up everything for God? A careful reading of the biblical text invites, or compels, the question.

The sanctified redemption of the firstborn, with its implication that life itself belongs to God, is brought together in Exodus with the ordained reenactment of the Israelites’ deliverance, thus underlining the Jews’ utter dependence on God in the moment of their collective birth as a nation. As Kass notes, the account presented by Moses himself in these chapters omits entirely his own role, together with Aaron, in implementing the first nine plagues. That presentation stands in sharp contrast to the later portrait of Moses in the wilderness, where we see him growing into his responsibilities as the great founder, lawgiver, and leader whose example will be the subject of rumination by so many later philosophers and statesmen.

For Maimonides, Moses in the years of the Israelites’ wanderings learns from God what he needs to know if he is to transmit a code of law for a people who will be a “light unto the nations.” For Machiavelli, Moses’ ruthless but necessary decisions make him a model of what it takes to establish new modes and orders of social and political organization. Indeed, on several occasions when the biblical text offers no independent evidence of God’s personal involvement, Moses makes his own claims to divine authorization for his actions—claims that exhibit the political wisdom of a leader who must gain or preserve the support of his people in a fragile situation.

Perhaps, however, the original liberation of the Israelites from four centuries of enslavement under a foreign power is explicable only by the miracles wrought by a divine intervention in human affairs—the most sweeping and purposive such intervention since the great Flood. The Haggadah for Passover pushes this view to the extreme by recounting the story of the exodus without ever once invoking Moses: deliverance is brought about “not through an angel, not through a seraph, not through a messenger, but by the Holy One, Blessed is He, Himself, in His own glory and in His own person.” This alternative view might even suggest some rabbinic uneasiness about the last lines of the Torah: “And there hath not arisen a prophet since in Israel like unto Moses, whom the Lord knew face to face, . . . and in all the mighty hand, and all the great terror, which Moses wrought in the sight of all Israel” (Deuteronomy 34:10-12).

In light of these apparent tensions, how is the relation between human agency and the power of God to be understood? That question runs all the way through the biblical narrative as it moves from the “people-forming Passover” on the last night of Egyptian bondage to the founding of a nation destined to be shaped by the divine law given in the wilderness, on the way to the promised land.