My thanks to Andrew T. Walker, Eli Steinberg, and Josh Beraha for joining the conversation about synagogue life during and after the pandemic. Each in his own way has broadened and enriched the discussion.

Andrew Walker offers a valuable comparative framework by reflecting on the experiences of Christian congregations, particularly evangelical churches. Well before COVID-19, some churches have offered what he names “digital spirituality.” By this he means “the ability for religious adherents . . . to mediate their spiritual lives through online communities, on their own terms,” as opposed to the in-person experience of “brick-and-mortar spirituality.”

I reported about parallel developments when synagogues pivoted to online services. Rabbis have marveled at their success in attracting hundreds, if not thousands, to view prayer services projected from their synagogues. Many proudly cite evidence of viewer satisfaction with the production values of the services and feedback they received from congregants about their pleasure at seeing services up close thanks to cameras sharply focused on the officiants. Rabbis also tout the high numbers of virtual attendees who presumably are attracted by the fine singing of cantors and choirs and thought-provoking sermons. Where congregants could see each other on the screen, they enjoyed reconnecting to one another and typing out chats during the services.

But, frankly, I heard nothing from the many rabbinic leaders I spoke with about enriched spiritual lives. Like Walker I am dubious about what such worship services evoke in viewers. Perhaps, I am skeptical about what is happening online because I have no idea what people mean when they use the catch-all term “spirituality.” I’ve learned from the sociologist Nancy Ammerman, a leading student of American congregational life, that most “spiritual” people never act upon their spiritual feelings to do anything, such as join a religious community. I’d welcome in-depth study of what viewers take away from online prayer services and whether video services serve as a substitute for in-person gathering as religious experiences.

Noting, as I also did in my article, the benefits to shut-ins who otherwise cannot participate in public worship, Walker offers a large and deserved dose of skepticism about the staying power of virtual religious services. How long will people continue to find the video temple worth their while? In his view, online services also lead to a coarsening of religious life through their pandering to consumerism and a thirst for feel-good religion.

We don’t as yet have sufficient evidence to judge whether most synagogue leaders, as distinct from members, are succumbing to this temptation. True, services have been abbreviated. But thus far clergy are motivated to shorten prayer services out of their concern for congregants suffering from Zoom fatigue. The new popularity of weekday prayer services also suggests that online worship need not necessarily lead to religious minimalism but has inspired some congregants to participate in prayer services with increased frequency. And the efforts to enlist volunteers to reach every member family with offers of support also suggest that ḥesed, acts of loving kindness, are on the upswing.

I also concur with Walker when he writes that “technology doesn’t so much shape the community as reveal its inner state.” Synagogues designed to meet the instrumental needs of their members but asking little in return may experience a sharper decline in membership or greater numbers of members wishing to “pause” their financial support. If the sole reason to join a synagogue is to benefit from particular services, and those are not available during the pandemic, why pay membership dues? By contrast, synagogues focused on inspiring their members to relate to the congregation as a religious community where Jews share mutual responsibilities and aspire to intensify their engagement probably are managing much better currently and face a brighter future.

By now it is a truism that the pandemic has been a great leveler. In the religious sphere, churches, synagogues, mosques, and temples of different faiths have all been shuttered during lockdowns and can only accommodate a fraction of their usual attendees when they are open. All houses of worship must address these challenges, and they tend to behave in similar ways. They also have been forced by circumstances to formulate their own ritual and liturgical policies in response to online prayer services. The most common question is whether religious rites performed during public worship may be enacted online. Catholic priests, for example, have debated the religious validity of “spiritual communion,” where the priest alone conducts Holy Mass, and then takes the Eucharist on behalf of everyone watching passively online.

The Jewish analogue to this question is whether online prayer gatherings constitute a minyan (a prayer quorum). Many rabbis have decided that emergency measures are in order and therefore any religious scruples must be secondary to the mission of holding the congregation together. Online services therefore tend to replicate exactly what is done when the congregation meets in person. But others have stood their ground either by rejecting the use of virtual media to deliver prayer services or by circumscribing their use. For example, they insist that prayers requiring a minyan may not be said when participants are not together physically. New precedents have been set during the pandemic, and there is no way to know whether congregations will be able to reinstate pre-coronavirus liturgical practices.

But our attention to the impact of the pandemic should not distract from recognizing longer-term trends affecting religious life in this country, another theme Walker raises. American exceptionalism when it comes to religion seems to be dissipating. Our society is following the same patterns previously observed in most European countries where religious participation has been in steep decline. Ninety-nine years ago, G.K. Chesterton famously pronounced America “a nation with the soul of a church.” One would be hard pressed to apply that description to the current scene in this country. Not only is it hard to discern a commonly accepted creed or set of values, but religion itself is treated with suspicion, if not contempt, by this country’s cultural elites and the masses of Americans are falling into line. Attendees in mainline Protestant churches, who represented 30 percent of churchgoers in 1975, constituted merely 11 percent by 2018. Despite continuing immigration from countries with large Catholic populations, the number of Americans identifying as Catholics continues to decline. Only evangelical Protestants have come close to holding steady, though they too are declining numerically, albeit at a slower pace. Increasing numbers of Americans state that they have no religion.

Jews, as they do so often, follow the same pattern as societies in which they live, only more so: synagogue membership has been in decline for decades; attendance has never been robust except on High Holy Days; and ever larger percentages identify as “Jews of no religion.” The coronavirus has exacerbated these trends, but no one should confuse the short-term impact of the pandemic with the decades-long erosion of Jewish religious participation.

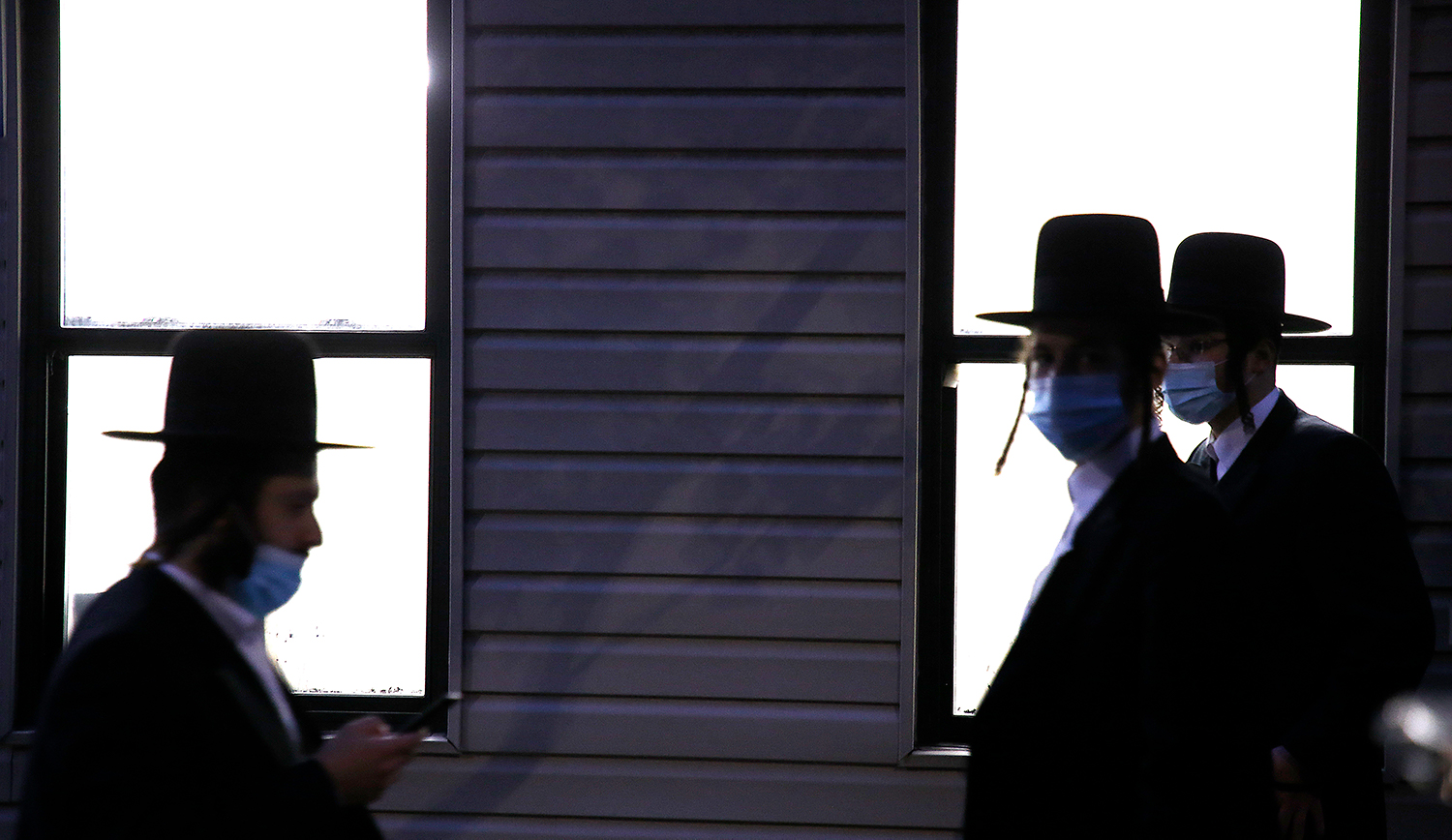

Eli Steinberg describes a vibrant Jewish community that bucks this trend. The Lakewood Yeshiva attracts roughly 8,000 young men who commit themselves to years of studying Torah Li-shmah, learning for its own sake—that is, for no instrumental purpose. Around that yeshiva, a robust community has grown, one that probably has the highest fertility rates in this country, which ensure further growth. In his response to my essay, Steinberg describes efforts to protect community members from the pandemic even as teams of healthcare specialists worked to devise safe ways to open key institutions of learning.

Steinberg writes eloquently about the contradictory policies of government officials who forbade gatherings for purposes of religious worship but sanctioned far larger marches where people massed to further favored political causes. While he is not the first to note the ensuing loss of trust in those officials, he is no less correct that such hypocritical policies are likely to undermine civic compliance during future crises. This potential danger does not threaten only Ḥaredim; it affects wide swathes of Americans across the country.

Steinberg also illuminates the distinctive ways Lakewood Jews—and by extension other sectors of ḥaredi Jewry and some Modern Orthodox Jews—conduct their lives. Because they reside in Orthodox enclaves, their lives revolve around their Jewish community. Synagogues are not the primary Jewish institutions for them, but part of a series of interlocking spaces where they gather. As a result, these tight-knit communities have built an entire way of life around daily social interactions—a lifestyle that’s impossible to maintain during long-lasting lockdowns. Yet, community leaders had to take into account safety concerns to ensure the virus would not surge without threatening this way of life.

Steinberg offers evidence about how his community has navigated the COVID-19 crisis in an exemplary fashion. But if, as he argues, “the media chose to focus on the most egregious violations of social-distancing protocols” among other ḥaredi populations, his essay offers a case study focused on perhaps the most responsible community and downplays the many other places where Orthodox Jews flouted health measures and paid a steep price for it in the form of surging cases and deaths. As it happens, from spring through the fall of 2020, I paid weekly visits to members of my own family who live in Brooklyn. Driving through different ḥaredi neighborhoods, I did not have to rely upon hostile and noncomprehending reporters to see firsthand the refusal of so many of my fellow Jews in those communities to wear masks and to maintain social distance. It is doubtful that the reports of surging cases in such precincts in Brooklyn and Queens, let alone in similar neighborhoods in Israel, were manufactured by journalists out to besmirch ḥaredi Jews. The resentment expressed by many Modern Orthodox Jews about the irresponsible behavior of too many ḥaredi Jews suggests that the Lakewood story, exemplary as it may be, is atypical of ḥaredi responses.

But Steinberg’s essay also highlights indisputable differences between Orthodox and non-Orthodox synagogues, differences brought into sharp relief by the recent lockdowns. Orthodox Jews found safe ways to gather for public worship, often at what Steinberg refers to as “porch minyanim.” Men and some women congregated safely at a distance from one another in backyards and driveways or other outdoor spaces to conduct prayer services thrice daily. When permitted, Orthodox synagogues ran multiple prayer services indoors to enable limited numbers to attend daily services while safely distanced from one another. By contrast, few non-Orthodox synagogues supported private minyanim. They either took services online or reduced their number. Many non-Orthodox synagogue buildings have been shuttered for over a year while most Orthodox synagogues opened as soon as government restrictions were lifted. Why the difference? The simple answer is that the former were not constrained by halakhah and therefore could run their services virtually. They had no need to hold in-person minyanim.

But there is a second reason: non-Orthodox synagogues rely almost exclusively on their clergy to act as officiants. Without them, the service cannot function. They simply have too few members who can lead prayers themselves. (Some Conservative and Reconstructionist synagogues have trained members who can read the Torah and lead weekday services, but too few to offer leadership for a multiplicity of minyanim.) All this represents a major historical reversal. With the emergence of synagogues in antiquity, Jews ceased to rely upon priests to serve as officiants. Many smaller Jewish communities did not have rabbis, let alone cantors to lead their services. Lay Jewish males led the prayers. (In some communities, lay females also led prayers for women.) That was true for my own ancestors living in small villages in Germany, as it was true in many shtetls in Eastern Europe and in small communities in areas inhabited by Sephardi Jews. As levels of Jewish literacy declined in many modern Jewish communities, rabbis and cantors assumed the role of priests; they alone knew how to lead services. Is it too much to hope that more non-Orthodox synagogues will train cadres of members to lead services now that the coronavirus has exposed this unfortunate and regressive state of affairs?

Josh Beraha has good reason to celebrate the important steps taken by some synagogues during the pandemic. The congregation he serves offers a model of creative leadership. I applaud his message of hope and encouragement as he surveys ways that synagogues have responded energetically during the pandemic.

Moreover, I agree with him that rabbis must venture forth from their synagogues “to ensure that Judaism flows outward toward people and the lives they live.” The days are long gone when rabbis could sit in their synagogue offices and assume that new members will seek them out. Awareness of that reality has been commonplace in rabbinical schools since the end of the last century. Perhaps the proactive approach embraced by the fast-growing Chabad movement has added a competitive threat to help motivate congregational rabbis. It has become far more common for rabbis to engage in Jewish learning with congregants at their offices and places of business. Some rabbis work with realtors to learn about new homeowners in their community and then extend a warm welcome as an initial step toward establishing a relationship with potential new members. “Torah and Brew” discussions in bars and other unconventional settings have become common.

But Rabbi Beraha wants to go even further. He calls for the radical transformation of synagogues, and although he is a bit vague on the details, he envisions the pandemic as a crisis too good to waste. “Will we use this disruption in Jewish life,” he asks, “to bring about a new synagogue model, whose ease of access and relevance can bring our people roaring into the next decades, fueled by a reenergized, forward-looking theology?”

For decades now, synagogues have been lambasted by critics for their cold formality and rigidity, their unchanging and unappealing religious services, and their benighted theological messages—despite the fact that anyone paying attention must notice just how much synagogues have evolved considerably in recent decades. Dana Evan Kaplan, a leading historian of recent developments in Reform Judaism, goes so far as to describe what has happened since the 1990s as a “synagogue revolution.” Across the denominational spectrum, synagogues have worked to inspirit their services through the use of music; substituted informal study sessions for high-flown rabbinic oratory, thereby making synagogue attendance more participatory; rabbis routinely offer their thoughts about contemporary issues, usually from a progressive perspective. What would the High Holy Days look like in most liberal synagogues without a thundering sermon advocating for gun control, racial equality, securing the environment, or other causes of the day?

Meanwhile, synagogue structures have been retrofitted to accommodate informal prayer spaces. Some congregations have installed faux coffee bars for people to gather informally. The list of innovations is endless: most notably women’s roles in synagogue life look nothing like they did 40 years ago; once-marginalized groups are welcomed through “audacious hospitality.” But with all these changes, attendance at synagogue services overall has continued to decline, even if some special “Rock Shabbat” or “Jazz Shabbat” services have seen an uptick in attendees once a month. Only shrinking minorities of non-Orthodox Jews claim to attend religious services with any regularity. And yet, the hope remains that with just a bit more fine-tuning, a few more radical changes, sermons attuned to the mood of the times—presto, synagogue life will revive.

My point in raising this reality is not to make a case for stasis but to reject the canard that synagogues remain fairly marginal to the lives of their liberal members, the population Rabbi Beraha wishes to address, because they are hidebound and unchanging. I can think of other forces at work: a Jewish population profoundly ignorant about its own culture and lacking in what used to be called synagogue skills—the ability to decode Hebrew words, let alone understand their meaning and allusions to the foundational religious texts of Judaism; a Jewish population that learned at home to regard synagogues and prayer as a sometime thing to be contemplated only on two or three days of the year; a population that has other interests and may not find anything a synagogue does nearly as alluring as entertainment venues; a population that has been educated at universities to think that believers are benighted, if not dangerous because they may become religious fanatics. The response of course is that the consumer is always right and any business failing to understand that truth is doomed. But what if the consumers are wrong because they view religion as a product or service solely of utilitarian use, because they insist on being consumers instead of active participants in an enterprise that is about something transcendent?

I expect that Rabbi Beraha understands the reality I am describing. When he makes the case for human connection that in-person gatherings can best provide, he writes about congregants who look into each other’s faces and eyes. My name for what he aspires to create in his synagogue is religious community: a place where Jews rely upon one another, who know one another, and join together at times of joy and sadness, who give of themselves to one another—and do so in a framework of Jewish commandments, rituals, and values. Not least, this is a place where fellow worshippers enrich each other’s prayer experiences and help one another achieve increased kavanah (religious intentionality) by being there in person and lifting their voices when praying together. Creating such a religious community, alas, is a slow process. If we must think of synagogues in business terms, what I’m describing is a retail enterprise to gather one Jew at a time, even as many rabbis are eager to provide Judaism wholesale to masses of Jews, and non-Jews.

Online services provide the illusion that hundreds, thousands, tens of thousands of people are part of the same religious enterprise. Knowing that so many viewers are tuning in undoubtedly tickles the fancy of some rabbis and congregants who believe their synagogue is winning a popularity contest. But are video temples capable of building a religious community?