Like fashion and food, political analysis of the Middle East has its fads, too. At one time, there was the “days are numbered” fad, as in “King Hussein’s days are numbered” or “the Saudis’ days are numbered.” In fact, the former died of natural causes after nearly five decades on the throne while the latter have proved surprisingly resilient, leader after leader. For many years, there was the “linkage” fad, the fervently held belief that resolution of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict unlocked the secret elixir to heal all of the region’s ills. No serious person makes that case any more, marveling instead at the impermeable bubble in which Secretary of State John Kerry keeps Israeli-Palestinian peace talks quarantined from the chaos swirling around the region.

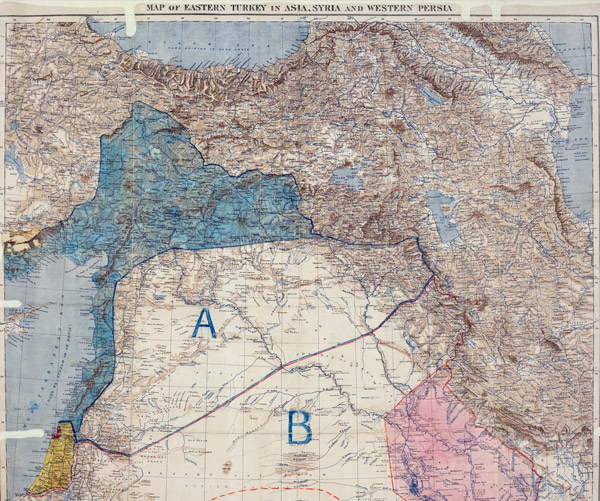

The current fad is about “the collapse of Sykes-Picot,” a phrase that triggers no fewer than 5.7 million hits in a Google search. This thesis takes various forms but, at its core, it is the idea that the system of largely artificial nation-states invented by the British and French at the end of World War I to safeguard their colonial interests—a system kept in place in the post-colonial period by decades of strong-man rule—is finally collapsing. In most versions of the story, the competing and often violently conflicting loyalties of tribe, sect, ethnicity, and religion are chiefly responsible for erasing these century-old lines in the sand.

Like the earlier fads, advocates can rightly cite certain objective facts to support their case. Fact: one Arab state, Sudan, has recently divided into two, largely along religious and tribal lines. Fact: the tragic history of the long-suffering Kurdish people is looking more hopeful than ever with the emergence of a largely effective, quasi-independent, refreshingly progressive (certainly by regional standards) Kurdish government in northern Iraq. Fact: after more than 40 years, the Assad family no longer has a firm grip on the Syrian state and its mosaic of populations, with large swaths of the country totally, and perhaps irretrievably, free from central government control. And fact: in just 15 years, an ideologically based, transnational non-state actor, al-Qaeda and its affiliates, has risen to the top of the national security agenda of both Western nations and status-quo states in the region. There are possibly other facts to add to this list.

In making his provocative case for the implosion of the Middle East, and the necessity therefore for Israel to devise a new regional strategy to confront the new threats it faces, Ofir Haivry adds some creative facts of his own. The Arab “spring,” he argues, “seriously rocked” Morocco and Jordan. The Western Sahara, he states, is “stirring,” and the Algerian regime is “facing calls for Berber self-definition.” The Hashemite kingdom of Jordan is facing a “potential break between the Palestinian-majority urban north and the Bedouin-dominated tribal south.” When you add all this together with the demise of regimes in Egypt, Libya, and Tunisia, and civil wars in Yemen and Syria, he concludes, “a presumptively monolithic ‘Arab’ region is being supplanted by a patchwork of identities and allegiances whose definition, patterns of organization, and prospective alliances are all yet to be played out.”

Whoa! Taken as a whole, this, analytically speaking, is balderdash. Given that the Arab region was “presumptively monolithic” only in the romantic imagination of besotted Westerners, the demise of the monolithic paradigm has no meaning. By and large, states have developed and survived as effective instruments of power and control, even at times of turbulence and upheaval.

Indeed, until the current events in Syria, one of the most striking aspects of the tidal wave of change across the region since December 2010 has been the uniquely national stories that have emerged. In contrast to the Arab nationalist wave that washed across the region in the 1950s and 1960s, this one has been state-focused. Egypt has been an Egyptian story, not an Arab story with major roles played by other Arab actors; similarly, Libya and Tunisia. Saudi Arabia has played a key role in Yemen and Bahrain but neither place has been the setting for some trans-Arab political earthquake.

As for the specifics of Haivry’s case, it is a corruption of language to say that the Jordanian and Moroccan kingdoms have been “seriously rocked” when neither has seen any significant violent protests and both kings—somewhat surprisingly in the case of Abdullah, less so in the case of Muhammad—remain firmly on their thrones, at least for now. One also needs to take account of the anti-Islamist, pro-statist counterrevolution in Egypt, which appears to have empowered a telegenic army general with more support and popularity in 2014 than a certain air-force general named Mubarak enjoyed throughout most of his 30 years of rule.

In his analysis of America, Haivry is closer to the mark. He is right to note that despite its “current troubles,” the U.S. is “still by far the only serious great power on the international scene.” He is also correct when he says that “political will is another matter,” a fairly light critique of the Obama administration’s over-correction to its predecessor’s perceived “irrational exuberance” (to borrow Alan Greenspan’s phrase) in the use of force as a tool of national policy. He is on no less firm ground in noting that “even a relative [American] retrenchment” will have considerable impact on Israeli national security calculations.

All that is fine, as far as it goes. But Haivry does not really connect his brief assessment of American strategy and policy with his fundamental thesis of the collapse of the Middle East state system.

States, as we have known them, have been around for several hundred years, but, more than any other country, America is responsible for the modern, post-World War II state system, with its international institutions, international law, and international regulations (i.e., treaties). It is no surprise that America benefits from this system, thrives in it, and has an interest in its survival. The demise of a state system that, to a great extent, was devised, nurtured, and sustained by America would be a BIG deal, complete with capital letters. Not even a disengaged American president, a neo-isolationist American Congress, and a preoccupied American public smug in the mistaken idea that America had become energy-independent would be able to remain indifferent to such an eventuality.

In fact, however, nothing like this is happening. Justified criticism of President Obama’s steely nonchalance toward Iranian troublemaking and Assad’s butchery notwithstanding, his administration has invested heavily in cauterizing the spillover from Syria and bucking up states across the region. Washington has spent huge sums to support Jordan, elevated Morocco to a “strategic partner,” developed an impressive network of integrated military and intelligence capabilities across the Gulf, and begun to correct the indulgence toward the Muslim Brotherhood that characterized policy toward Egypt in 2012-2013. Similarly, U.S.-Israel defense and intelligence cooperation has hit new heights, at least on the professional and technical levels.

To be sure, none of this is enough to prevent a debacle, in both human and strategic terms. The Obama team’s focus has been overwhelmingly defensive in nature, choosing to strengthen our allies’ capabilities rather than push back against Tehran’s egregious behavior (including brazen terrorism in our nation’s capital), or the ideology of radical extremism (including the brand that motivated the Morsi presidency in Egypt), that together form the root causes of much of the region’s insecurity.

But a full critique of the administration’s Middle East policy is the stuff of another essay. In terms of Haivry’s thesis, it suffices to point out that even the Obama administration—the most reluctant to wield power abroad since the presidency of Jimmy Carter—recognizes the vital role that states play in the international system, including in the Middle East, and has focused its efforts on shoring them up. (As an aside, it strains credulity to imagine that, as Haivry suggests, India—an impressive democracy with which Israel shares a fear of radical Islamism and an interest in developing closer ties—will ever play that role, let alone develop into a “candidate for partnership” on the U.S.-Israel model.)

The Middle East in 2014 is a depressing place. Bombs are going off in so many places that it’s tough to keep up. A rejuvenated al-Qaeda has turned the Syria-Iraq frontier into an Arab version of the border between Afghanistan and Pakistan. Turkey, a NATO member-state—a NATO member-state!—has more journalists in jail than any country in the world. In Egypt, liberals are seeking refuge in authoritarians to protect themselves from Islamists. And in Syria, a cruel ruler on the road to political redemption is purposefully starving children and, with the active support of one permanent member of the UN Security Council, and the acquiescence of the others, is getting away with it.

For Israeli strategic thinkers, all this poses enough difficult choices, and enough bad and worse options, to grapple with. Still, it is not wrong—or, as Haivry suggests, immoral—for Israel to shore up a system that has served Israel well and that may even, in the case of Egypt, be shoring itself up on its own. Yes, uncertainty in Cairo and Damascus has brought an end to what I have elsewhere called the “forty-year peace”: the period since the October 1973 war during which Israel could count on the fact that neither Egyptian nor Syrian rulers had an interest in resuming direct, conventional war against the Jewish state. But heightened uncertainty does not mean the collapse of the entire Middle East state system, allegedly abetted by a now-and-forever American indifference to the outside world. It suffices for Israel to address difficult problems as they are, not as they are imagined to be.

________________

Robert Satloff is executive director of the Washington Institute for Near East Policy and the author of books on topics ranging from the domestic politics of Jordan to the search for Arabs who saved Jews during the Holocaust.