To begin with, here are the generally undisputed facts of, to borrow Martin Kramer’s title in Mosaic, “What Happened at Lydda”:

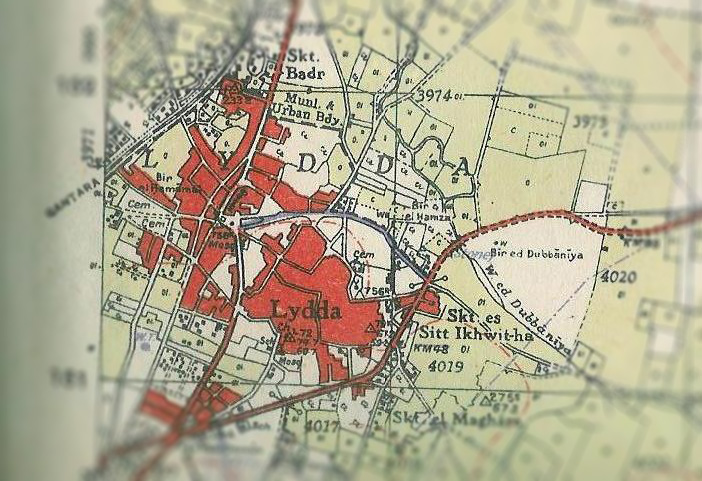

On July 11, 1948, as part of the Israel Defense Forces’ “Operation Dani,” designed to take control of the road between Tel Aviv and (Jewish) west Jerusalem, armored vehicles and jeeps of the 89th Battalion, 8th Brigade, commanded by Lt. Colonel Moshe Dayan, dashed down from Ben-Shemen through the Arab town of Lydda to the outskirts of its sister town of Ramleh and then back to Ben-Shemen, machineguns blazing. In the foray, which lasted about three-quarters of an hour, dozens of Arabs were killed.

Minutes later, four companies of the 3rd and 1st Battalions of the Palmah’s Yiftah Brigade, 300-400 soldiers in all, pushed into Lydda and took up positions in the center of town. In the following hours, Arab men, and some women, were herded or made their way to the town’s medieval Church of St. George and the Great Mosque next door. Among the town’s 20,000-30,000 inhabitants and refugees were several hundred militiamen, some of whom had not been disarmed. There was no formal surrender, but the Israelis thought the battle was over. The night passed quietly.

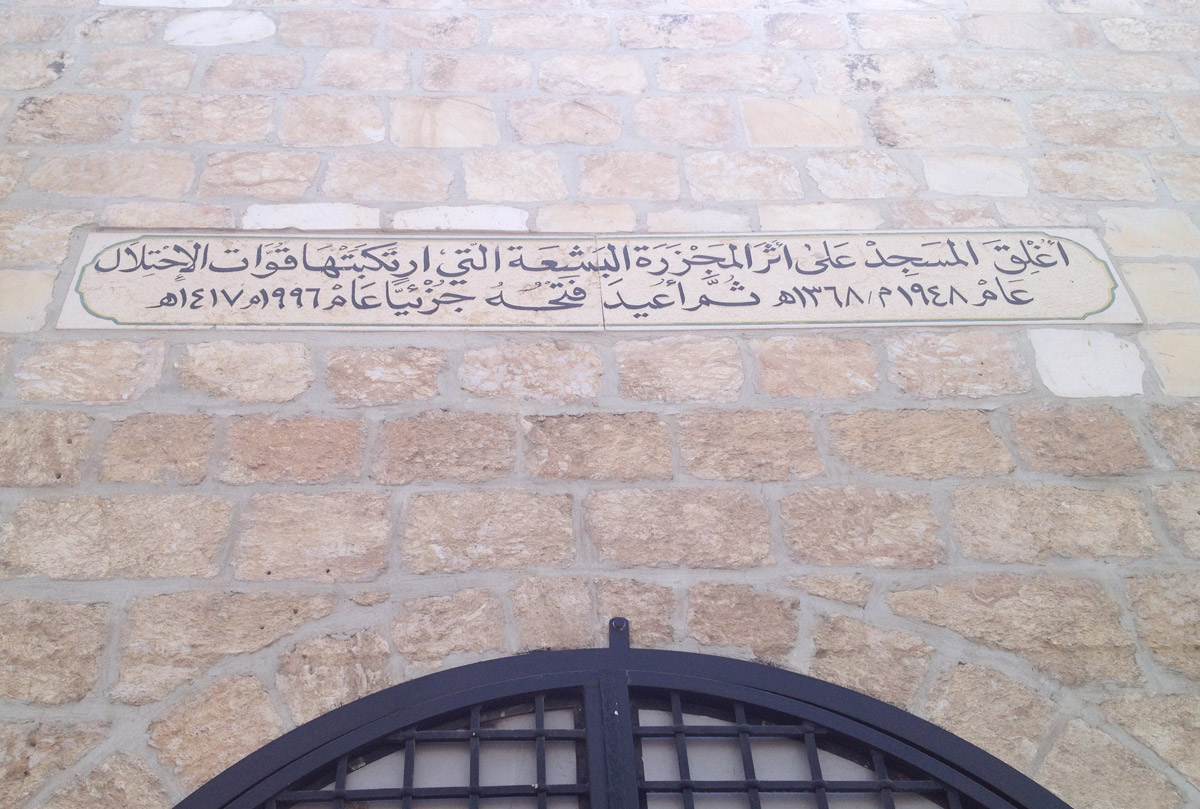

Just before noon on the following day, July 12, two or three Jordanian armored cars drove into town and a firefight broke out; the Yiftah men suffered a number of casualties. The sound of the battle triggered sniping by local militiamen from windows and rooftops. The Israelis felt hard-pressed, confused, perhaps even panicky. Moshe Kelman, commander of Yiftah’s 3rd Battalion, ordered his men summarily to suppress what they would later call a “rebellion,” and to shoot anyone “seen on the street” or, alternatively, at “any clear target.” The troops also fired into houses. One of the targets, where dozens apparently died, was the town’s small Dahmash Mosque.

Later that afternoon and during the following day, the Israelis expelled the population of Lydda—and of neighboring Ramleh, whose notables had formally surrendered—eastward toward the Jordanian-held West Bank. Today, the descendants of the refugees from these two towns fill the camps around Ramallah and Amman.

And now we have another story, a story of two cherry pickers, each of whom distorts history in his own way.

In his best-selling book My Promised Land, the journalist Ari Shavit distorts in the grand manner, by turning Lydda into the story of the 1948 war and indeed of Zionism itself. Insisting that, at Lydda, “Zionism commit[ed] a massacre,” he writes: “Lydda is our black box. In it lies the dark secret of Zionism.” (As an aside, I would suggest here a much more telling “black box” or key to understanding both Zionism and the conflict. It is Kibbutz Yad Mordekhai, where for four to five days in May 1948 a handful of Holocaust survivors held off the invading mass of the Egyptian army, giving the Haganah/IDF time to organize against the pan-Arab assault on the newborn state of Israel.)

As for Martin Kramer, writing in Mosaic, he distorts by whitewashing and/or ignoring the expulsion and by effectively denying that it was preceded by a massacre. Instead, he writes, Lydda was a story of “collateral damage in a city turned into a battlefield”: not a black box but a “gray zone.”

Both Shavit and Kramer present us with a methodological problem: neither of them uses or refers to contemporary documentary evidence—which, in my view, is the necessary basis of sound historiography. Documents may lie or mislead, but to a far lesser degree than do veterans remembering (or “remembering”) politically and morally problematic events decades after they have occurred. In My Promised Land, Shavit offers neither footnotes nor bibliography; concerning 1948, he refers only to interviews (about which he provides no details) that he himself conducted decades ago. Kramer, a Middle East expert, relies on interviews done by others, also decades ago.

As it happens, the problematic events at the Dahmash Mosque are not mentioned at all in contemporary IDF documents. One can assume that something very nasty did occur there, since both Jewish and Arab oral testimonies agree on this. But the circumstances surrounding the incident—were the people in the mosque armed or were they disarmed detainees; did they or did they not provoke the Israelis by throwing grenades at them?—remain unclear. I’ll return to this incident below.

Now to our two authors.

In My Promised Land, Ari Shavit does something unusual, perhaps even unique, which (apart from his abilities as a writer) may help to account for the book’s American success. He simultaneously satisfies three different audiences. Mainly through his moving portraits of Holocaust survivors, he presents a persuasive justification of Zionism, thus catering to supporters of Israel. But as a bleeding-heart liberal he also caters to the many Jews and non-Jews—call them agnostics—who now find fault with Zionist behavior over the decades. And finally he caters to forthright Israel-bashers: those for whom every new or rehashed or invented detail of Jewish atrocity is grist for the anti-Israel mill.

His chapter on Lydda is the cameo performance. Following the book’s publication, in appearances before largely Jewish audiences, Shavit heatedly argued that he had been misunderstood, enjoined readers to view “Lydda” in context, and denied that he had posited it as the defining narrative of Zionism/Israel. The columnist doth protest too much, methinks. After all, Shavit engineered advance publication of the chapter as a stand-alone piece in the New Yorker, and it was he who defined “Lydda” as the key to Zionism.

Well, it isn’t and it wasn’t. Yes, Lydda was simultaneously the biggest massacre and biggest expulsion of the 1948 war. But no scoop there; decades ago, Israeli historians described what happened in great detail. Lydda wasn’t, however, representative of Zionist behavior. Before 1948, the Zionist enterprise expanded by buying, not conquering, Arab land, and it was the Arabs who periodically massacred Jews—as, for example, in Hebron and Safed in 1929. In the 1948 war, the first major atrocity was committed by Arabs: the slaughter of 39 Jewish co-workers in the Haifa Oil Refinery on December 30, 1947.

True, the Jews went on to commit more than their fair share of atrocities; prolonged civil wars tend to brutalize combatants and trigger vengefulness. But this happened because they conquered 400 Arab towns and villages. The Palestinians failed to conquer even a single Jewish settlement—at least on their own. The one exception was Kfar Etzion, which was conquered on May 13, 1948 with the aid of the Jordanian Arab Legion, and there they committed a large-scale massacre.

In any event, given the length of the war, the abundant quantity of Jewish casualties—5,800 killed out of a population of 630,000—and the fact that the Arabs were the aggressors, the conflict was relatively atrocity-free. By my estimate, all told, Jews deliberately killed 800-900 civilians and POWs between November 1947 and January 1949. Arabs killed approximately 200 Jews in similar circumstances. Compare this, for example, with the 8,000 Bosnians murdered in Srebrenica, in civilized Europe, over three days in July 1995 by an aggressor people, the Serbs, who were never seriously in peril.

As for expulsions: in most places in 1948, Arabs simply fled in the face of actual or approaching hostilities, while some, as in Haifa in April, were advised or instructed by their own leaders to evacuate. Most were not expelled, although Israel subsequently decided, quite reasonably in my judgment, to bar the refugees from returning.

Shavit, while checking off the relevant boxes, effectively fails to put “Lydda” in context: the context, that is, of a war initiated by the Arabs after the Jews had accepted a partition compromise and in which the Jews, three years after the Holocaust, felt they faced mass murder at Arab hands. Yes, Shavit does allow in passing that the Arabs rejected the UN partition plan of November 1947. But he writes: “[Immediately afterward] violence flares throughout the country”—as if it were unclear who started the shooting and as if the Palestinians were not responsible for a war that resulted in occasional massacres and masses of refugees.

Martin Kramer’s cherry picking is of a different order. Declining to look at or judge Shavit’s book as a whole, he zooms in on what happened in Lydda on July 11-13, 1948 and especially on the events at the Dahmash Mosque at around 1:00 p.m. on July 12. Describing and quoting Shavit’s account and comparing it with the testimony of various Palmah soldiers 30 or 40 years later, he shows how Shavit has manipulated and tilted the evidence to blacken Israel’s image. He is particularly critical of Shavit’s contention, for which Shavit cites no source, that the Israelis also murdered the eight-man detail assigned to dispose of the Arabs’ bodies. In all, Kramer questions Shavit’s integrity.

Fair enough. But Kramer clearly has an agenda. He more or less justifies the soldiers’ behavior by citing the veterans’ testimony that grenades were thrown at them from the mosque, prompting them to fire a rocket (or rockets) at the building. But they would say that, wouldn’t they, after the bodies of dozens of men, women, and children were subsequently peeled off the walls? The mosque stood—and stands—as one of several contiguous buildings in an alley. In the dust and heat and noise and terror of the moment, who could have seen and said with certainty from which building or rooftop a grenade, or grenades, were thrown (if any, indeed, were thrown)?

Dozens of documents were produced in July 1948 by Yiftah Brigade headquarters, the 3rd Battalion, and the IDF general staff about what happened in Lydda during those days, and they are preserved in Israeli archives. As I noted above, none of them mentions the mosque incident. Perhaps those who wrote them knew why.

But the existing documents are crystal-clear on two points, both of which Kramer obfuscates or elides: that there was mass killing of townspeople by Dayan’s July 11 column and, subsequently, even apart from the mosque incident, in the suppression of the sniping; and that the slaughter was followed by an expulsion. About the latter, all that Kramer tells us is that on the morning of July 13, the Israeli intelligence officer Shmaryahu Gutman negotiated with town notables the release of the detained Arab young men, with the notables agreeing to a mass evacuation as a quid pro quo.

There is no contemporary IDF documentary reference to this negotiation or “deal”; the story rests solely on Gutman’s say-so. If there really was such a deal, it apparently lacked authorization from Gutman’s superiors, since at 6:15 p.m. on July 13, Dani HQ cabled Yiftah HQ as follows: “Tell me immediately, have the Lydda prisoners been released and who authorized this?” Kramer adds, as a sort of cover, that Israeli troops “encouraged” the evacuation. Nothing more.

But the documents tell us a straightforward and radically different story. At a cabinet meeting on June 16, 1948, Prime Minister and Defense Minister David Ben-Gurion defined Lydda and Ramleh as “two thorns” in the side of the Jews; in his diary for May and June he repeatedly jotted down that the towns had to be “destroyed.” When news of the shooting in Lydda reached IDF HQ at Yazur after noon on July 12, Yigal Allon, the commander of Operation Dani, pressed Ben-Gurion for authorization to expel the inhabitants. According to Yitzhak Rabin, then serving as Allon’s deputy, Ben-Gurion gave the green light. At 1:30, Rabin issued the following order to the Yiftah brigade: “(1) The inhabitants of Lydda must be expelled quickly, without attention to age. . . . (2) Implement immediately.”

A similar order went out from Dani HQ to the Kiryati Brigade, whose 42nd Battalion had occupied Ramleh. In both towns, the troops began expelling the inhabitants. At 11:35 a.m. on July 13, Dani HQ informed the operations office of the IDF general staff that the troops “are busy expelling the inhabitants.” At 6:15 p.m., Dani HQ queried Yiftah HQ: “Has the removal of the population of Lydda been completed?” By evening, the two towns had been cleared.

It is also abundantly plain from the documents that (although the Hebrew term tevah, slaughter, was studiously avoided), the expulsion was preceded by a massacre, albeit a provoked one. Dozens if not hundreds of Arab civilians were shot in the streets and in their houses. Yiftah Brigade intelligence, summarizing the events a few days later, wrote that in Lydda on July 12, the 3rd Battalion had killed “about 250 [Arabs] and wounded a great many.” (The figure appears in the July 1948 documents, not only in the 1950s “official history of the Palmah” cited by Kramer.) For their part, Yiftah’s soldiers had suffered two-to-four killed, two of them apparently as a result of fire from troops of the Jordanian Arab Legion.

This disproportion speaks massacre, not “battle.” Yet Kramer calls what happened “A Battle with Two Sides” and quotes the Israeli historian Alon Kadish, who suggests that the Yiftah body count was wrong or, alternatively, that 250 was the number of Arab dead during all of the fighting in and around Lydda between July 9 and July 18. In her biography of Yigal Allon, the historian Anita Shapira dismisses Kadish’s arguments as “implausible.” I would say the same, basically, about Kramer’s description of what happened.

______________

Benny Morris is a professor of history at Ben-Gurion University and the author of, among other books, 1948: A History of the First Arab–Israeli War (Yale, 2008).

More about: Ari Shavit, Lydda, Martin Kramer, Massacre, My Promised Land, Zionism