In his essay in Mosaic, Jack Wertheimer, building on the terminology of the historian Jeffrey Gurock, divides today’s Modern Orthodox world into “resisters [of modernity] attracted by haredi Judaism and accommodators more willing to adapt Jewish law to 21st-century ethical sensibilities.” Given my professional position, I guess I would be placed in the accommodators’ camp. But it is not the goal of Yeshivat Chovevei Torah Rabbinical School to produce rabbis who accommodate Judaism to the Western world. Rather, our aim is to harness the gifts of modernity in enabling us to learn and understand more Torah and to live lives that better connect us to God, the Jewish people, and the world: the goal of Modern Orthodoxy in general.

Modern Orthodoxy as it developed in 20th-century America was dynamic, vibrant, challenging, and filled with new insights into Judaism. This was made possible not by taking in the values of modernity wholesale but by maintaining a positive attitude toward those values and not opposing them merely because they were foreign. At its best, Modern Orthodoxy represented an embrace of the idea that the world around us could help Jews, not just hurt them. It is this Modern Orthodoxy, willing to listen to voices from without and within, that we need to revitalize.

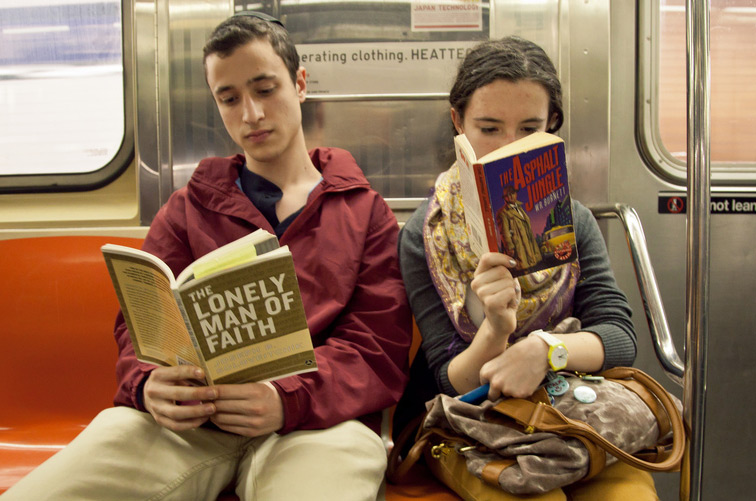

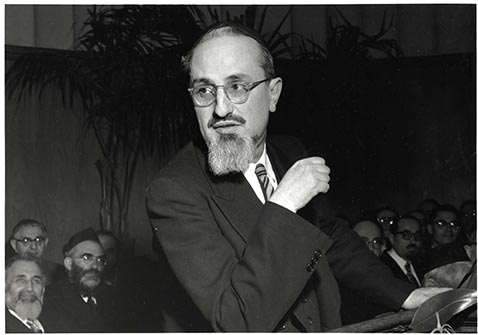

This is the very paradigm that was under siege twenty years ago when Rabbi Avi Weiss wrote his “Open Orthodox Manifesto.” Important and controversial Orthodox thinkers, including Rabbis Yitz Greenberg and David Hartman, were being shunned by the so-called Modern Orthodox establishment. Even Rabbi Shlomo Riskin, the founder and former spiritual leader of New York’s Lincoln Square Synagogue, was not allowed to speak at Yeshiva University. There was a sense of despair that the Modern Orthodoxy of the 1950s and 1960s—an era in which Rabbis Emanuel Rackman, Yitz Greenberg, and Eliezer Berkovits, and (in Israel) the philosopher Yeshayahu Leibowitz, were household names—had been lost. Even as Rabbi Saul Berman’s Edah initiative, noted by Wertheimer, succeeded in restoring a certain pride in the name Modern Orthodox, there was legitimate concern that the movement was coming to represent an ossified and unimaginative type of Judaism, always looking fearfully over its right shoulder. Hence “Open Orthodoxy.”

Fortunately, we are in a different situation today. In certain circles, Modern Orthodoxy is returning to its roots and coming back to life. After decades of struggle and hard work by the Jewish Orthodox Feminist Alliance, Aguna Inc., and many others, America now has an Orthodox rabbinical court dealing with the needs of women whose husbands have refused to give them a writ of Jewish divorce. Under the able leadership of Rabbi Simcha Krauss, the court is open to considering halakhic procedures of the past that have been lost to us in 21st-century America and Israel. Rabbis associated with the new International Rabbinic Fellowship and other Modern Orthodox organizations will undoubtedly support Rabbi Krauss’s rulings.

Similarly, Rabbi Marc Angel has established the Institute for Jewish Ideas and Ideals, bringing back the diversity of opinions, even the vibrancy inherent in a certain irreverence for authority, previously characteristic of Modern Orthodoxy. Through the institute’s journal Conversations, thousands of discussions have been sparked across America, and future Modern Orthodox leaders are being encouraged to appreciate and engage with challenging opinions through campus fellows’ programs. Yeshivat Maharat in the United States and at least three different programs in Israel train women to be teachers, halakhic thinkers, and decisors, and, in the case of Yeshivat Maharat, to go out and lead their own communities.

The Modern Orthodoxy of the past was not built solely upon controversy and irreverence for authority; it combined an awe of Judaism with an appreciation for what an engagement with modernity could do to make us better Jews and scholars of Torah. It is this balance that we need to retrieve. Indeed, there is even a great deal that the most open-minded and truly modern Orthodox Jew has to learn from the haredi world. Since the biblical prophet Isaiah bids the entire Jewish people to be “haredim,” shaking at the word of God, one thinker has even proposed adopting the term “Modern Haredi.” We need to be passionate about our Torah and our Yiddishkeit; we need to be in awe of the divine message and even more truly in awe of God. All this, while maintaining our engagement with the outside world and the diverse opinions that are a hallmark of our camp.

The exciting and courageous Modern Orthodoxy of yesteryear is back. It may still be most active under the surface, but the energy and potential are powerful. Rabbi Yaakov Perlow, the Novominsker Rebbe, was correct in pointing to the growing influence of the nearly 90 rabbis who have graduated from Yeshivat Chovevei Torah over the past ten years, most of whom work in Jewish communal life and fully 40 percent of whom occupy pulpits spanning the globe.

Now is indeed the time to reclaim Modern Orthodoxy as a vibrant, creative, and open movement. Accordingly, many of us no longer speak of Open Orthodoxy as a separate stream but rather of bringing back the real Modern Orthodoxy: the kind in which an Orthodox journal could print an article like Rabbi Norman Lamm’s “Faith and Doubt,” which claims doubt as part of our religion, or an article by Rabbi Eliezer Berkovits accompanied by a note stipulating that the content is not necessarily in consonance with editorial opinion.

Jack Wertheimer has laid down a challenge: can we rejuvenate the proud tradition of Modern Orthodoxy and connect it to our generation? From my vantage point, the answer is yes. With God’s help and with humility, awe, and the passion to explore the infinite depths of God’s Torah, we can revitalize Modern Orthodoxy.

______________

Asher Lopatin is president of Yeshivat Chovevei Torah Rabbinical School in New York. Educated at Boston University and Oxford, he received rabbinic ordination at Yeshivas Brisk in Chicago and Yeshiva University’s Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological School. He thanks Eric Elder for editorial assistance.