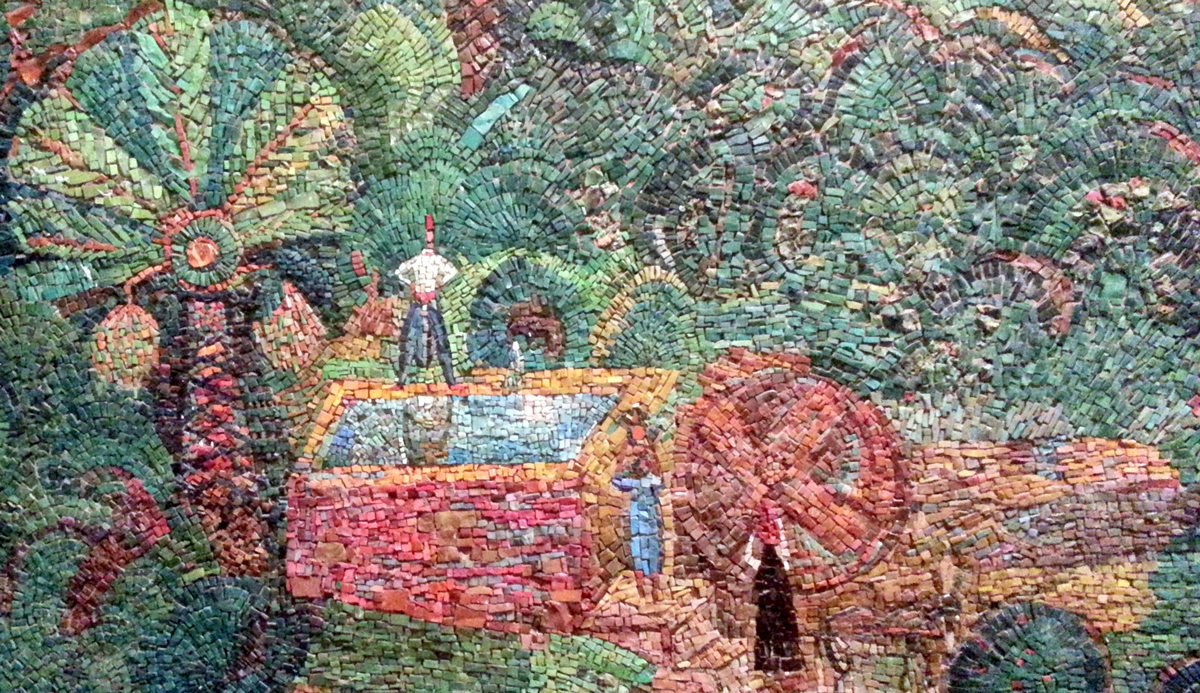

A detail of a mosaic wall showing orchards and a fountain outside old Jaffa by the Israeli artist Nachum Gutman. Wikipedia.

Time can play odd tricks on us when we experience it as our own times—the times in which we’re living. Matters that totally possess us for a week or even a year are swiftly succeeded by others; these in turn can so occupy our lives that we lose any sense of what mattered yesterday. All the while, the months and years slide by, and suddenly we may often be quite unsure of the precise year or duration of all these momentous happenings. It’s as if we’ve been sitting too close to the screen.

But there are other ways of minding time. Walking with the help of Hillel Halkin through the tumultuous times of Yehudah Leib Gordon, one sees many of the broader patterns of modern Jewish social and intellectual history coming into focus: the works and dreams of the 19th-century East-European movement of Jewish enlightenment, the Haskalah in all of its different guises, followed by the multitudinous sea-changes that swept the region under fin-de-siècle Tsarist reaction, the Hebrew revival, Zionism, Bundism, and Yiddishism in all of their forms.

Seen at our remove, as collective ideas and movements of mass action, these may come across with a certain logic and consistency. At the same time, viewed through the microscope of a master cultural historian and literary sleuth like Halkin, the deeds and mental states of a Yehudah Leib Gordon and many of his contemporaries also take on an intense and urgent vividness. They, too, lived close to the screen; they, like us in real time, were struggling to steer a straight path through the vortices of unfolding events—to make coherent sense of them and to chart a way forward.

It’s all rather gripping if one is gripped by the drama of Jewish history for its own sake, or as an aid to understanding one’s past. What leaps off the pages, whether prose or verse, is the sheer will and guts of so many individual Jews (albeit still a small minority of the whole) to fight for change, often risking all that they possessed. The Hebrew literary scene itself had a heroic quality about it. Without a country or an established political-cultural base, aimed at a readership that might not be there tomorrow, Hebrew writing migrated from city to city, region to region, leaping from one failing publisher to another—and somehow survived until modern Hebrew was established and prevailed in the land of Israel.

But what, then, of Gordon’s poetry itself? The truth is that even in Halkin’s expert and powerful English renderings, it probably doesn’t speak to many of us. And although Halkin’s helpings are generous, they are still excerpts, after all: who, today, has the patience to sit through 200 lines of verse composed in the high style? Among readers of English, in any event, the massive retreat from long-winded and ornamental language that seems to have come upon us with World War I and the hard-baked Hemingway style—and that has been heavily reinforced a century later by the culture of sound bites and Twitter—has put the likes of long-breathed Gordon into permafrost.

Sadly, moreover, if dead poets’ societies don’t generate many “likes” in today’s English-speaking world, the same can be said, with certain reservations, about Hebrew-speaking Israel. In a “Name Your Favorite Poets” poll conducted in 2005 for the Israeli Ynet website, the first five spots were occupied by Natan Alterman (by a large margin), Leah Goldberg, Rachel (Bluwstein), Yehuda Amichai, and Ḥayyim Naḥman Bialik. All but Bialik are 20th-century poets; Yehudah Leib Gordon didn’t even make the top 100. Further weighting the results, as the pollsters noted, is that select passages from all of the top five poets are learned by almost every Israeli schoolchild and, even more telling as a key to popularity, have been widely set to music. Meanwhile, the “old,” pre-state Hebrew literature has long been abandoned by the Israeli high-school curriculum. In your matriculation exams you may be asked to comment on a couple of medieval “Golden Age” poems and of course Bialik, the Zionist “national poet” (and a bit of a postmodernist avant la lettre), but most Israelis, even among the better educated, will probably reach adulthood without ever having read a word of Yehudah Leib Gordon or the other fabled writers of the Hebrew Enlightenment.

But as they say in Hebrew, az mah, “so what”? For the multiculturalists of the far left who have heavily infiltrated both Western and Israeli school systems, there’s nothing here to apologize for or to regret. “World” literature must take precedence over national (or Jewish) literature, and “universal” values over national (or Jewish) values. Nor, where Israel is concerned, is this solely a matter of the left. As soon as the state was founded, some of its leading writers set about questioning the relevance of its immediate progenitors and indeed of Zionist values altogether.

Their influence proved pervasive. Recently, under my supervision, a Dartmouth senior tracked Israeli grade-school anthologies across five decades: the exercise disclosed a steady shift away from historically Jewish content to more “cosmopolitan” fare. Yehudah Leib Gordon, whose poem “The Tip of a Yod,” insightfully dissected by Halkin, was a launchpad for Jewish feminism, would have found a sad irony in this supposed progression.

Within this irony lies another. The Hebrew language that Gordon and his peers struggled to modernize, calling up every ancient word they knew, minting new ones, and often magically transmuting old to new—as with Gordon’s most famous linguistic legacy, ḥashmal for electricity, which adopts a term for brightness in the vision of the prophet Ezekiel that the Greek Septuagint renders as elektron or amber—would soon indeed spring to life on a scale they could never have imagined. And yet, for millions of Israelis who today write and speak Hebrew with ease, this literary and linguistic heritage is virtually a closed book.

It’s not just that Israeli state schools (religious schools excepted) have made increasingly short shrift of Bible, Talmud, prayer book, and the rest of the Jewish heritage that formed the thematic or stylistic frame of reference for Hebrew literature up until the end of the 19th century. It’s also that anyone without a grip on the intricately classical grammar and word-stock of these sources—skills possessed today by few Israelis, secular or religious—will find the path to understanding effectively blocked.

When Eliezer Ben-Yehudah, a younger contemporary of Gordon, had his fantastical vision in 1879 of a Hebrew-speaking return to the Land, it was for one purpose alone: to preserve the Jewish people’s troth to their great literature. Of this part of Ben-Yehudah’s vision, little remains. Will the bond that Israel has since tied with its new Hebrew identity prove to be less a Gordonian than a Gordian knot? For us, sitting close up to the screen, that may be the way it looks. But a rediscovery of the Haskalah and its relevance to the Israeli cultural predicament is long overdue. And history has taught us that the Jews do have an extraordinary propensity for reconfiguring their language and their culture.