Language

And could the story of the Tower of Babel actually reflect a dim folk-memory of its breakup?

I’ve been spared an encounter with the neologism until lately. But, frankly, now that I have made its acquaintance, I find it idiotic. (And don’t get me started about “goysplaining.”)

Only in Schopfloch, as far as I know, have a large number of originally Jewish words survived in the speech of the local populace to this day.

In some cases, changes were minor. In others, Yiddish phrases were transformed nearly beyond recognition.

New borrowings and old ones.

Quite a few masculine and feminine Hebrew words, when pluralized, take the form of the opposite gender. Why?

The language of Paul Celan.

Some paleolinguists have floated the idea of an original human language they call “Proto-Sapiens.” Is that what our ancestors were speaking when they built the Tower of Babel?

Israeli politicians have in recent decades become obsessed with calling each other poodels.

A recently discovered letter explains.

Amid the familiar clutter of vowels and cantillation marks, a few strange dots appear. They have no obvious function, and yet they go back thousands of years. Their purpose is . . .

Nachman Blumental.

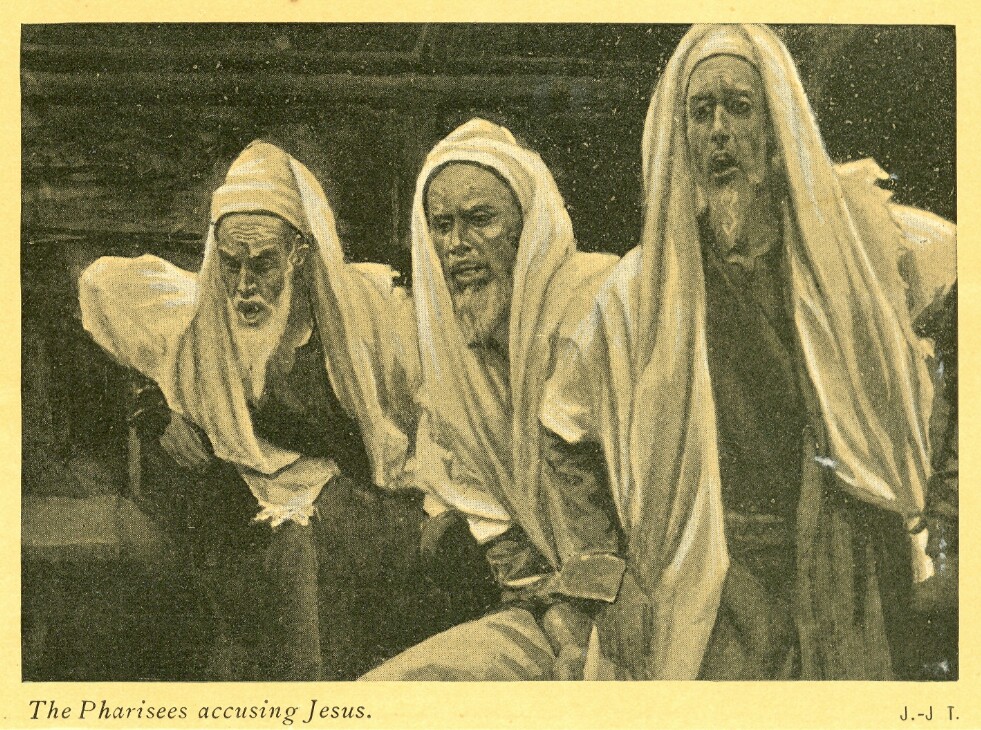

A desecration of what is most sacred.

A Mosaic reader was able to solve the mystery of the Yiddish expression tapn a vant, “to grope a wall.”