The Memoirs of Ruth Wisse

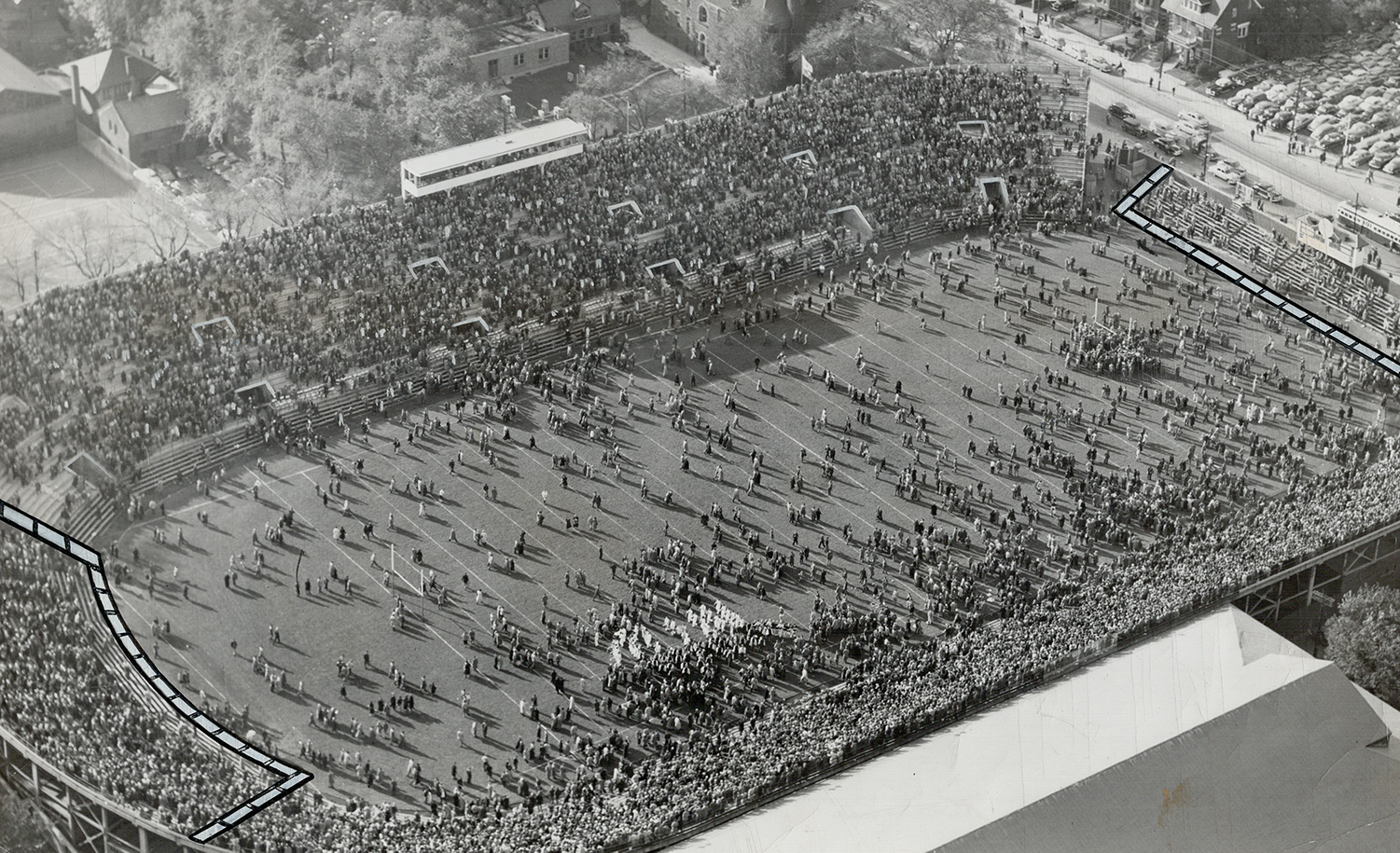

What I witnessed in my two decades of teaching at Harvard.

At arguably the moment of Harvard’s greatest involvement with Jews and Judaism, new movements in (anti-)intellectual thought started to creep in, too.

From academia to philanthropy to journalism, my experience with Jewish leadership has been by turns discouraging and inspiring.

Contention was so much a part of modern Yiddish culture that, in any study of that culture, it was all but taken for granted.

I expected the women’s movement to evaporate as quickly as it had materialized. It was the worst cultural prediction of my life.

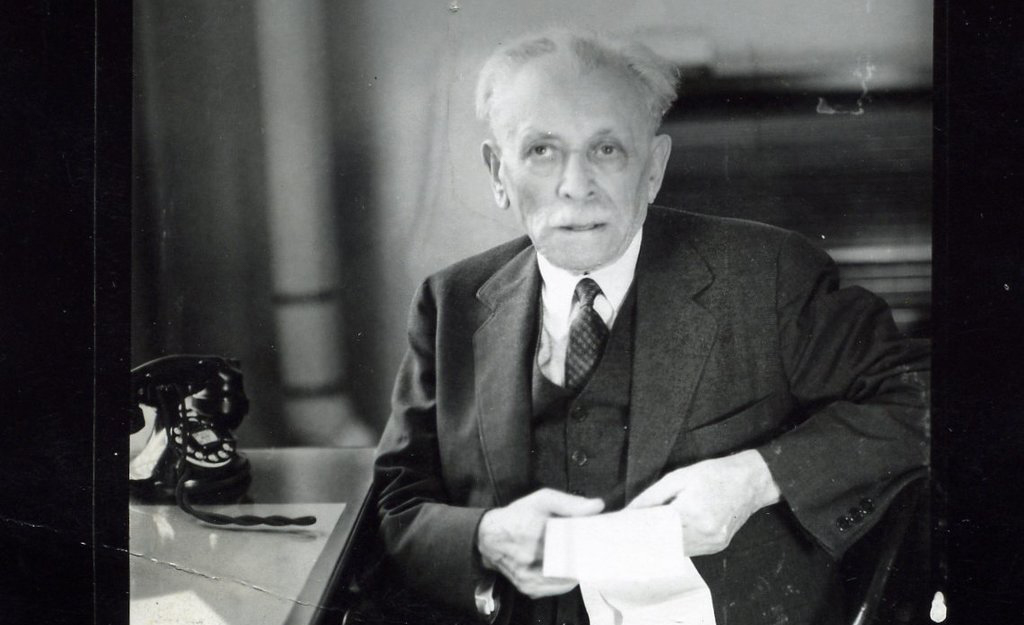

On making one’s way into the “intimidatingly smart” realm of the New York Jewish intellectuals, and the company of I.B. Singer.

For me, living in Israel is a moral imperative. There is no elegant or painless way to describe why, after a year, we left.

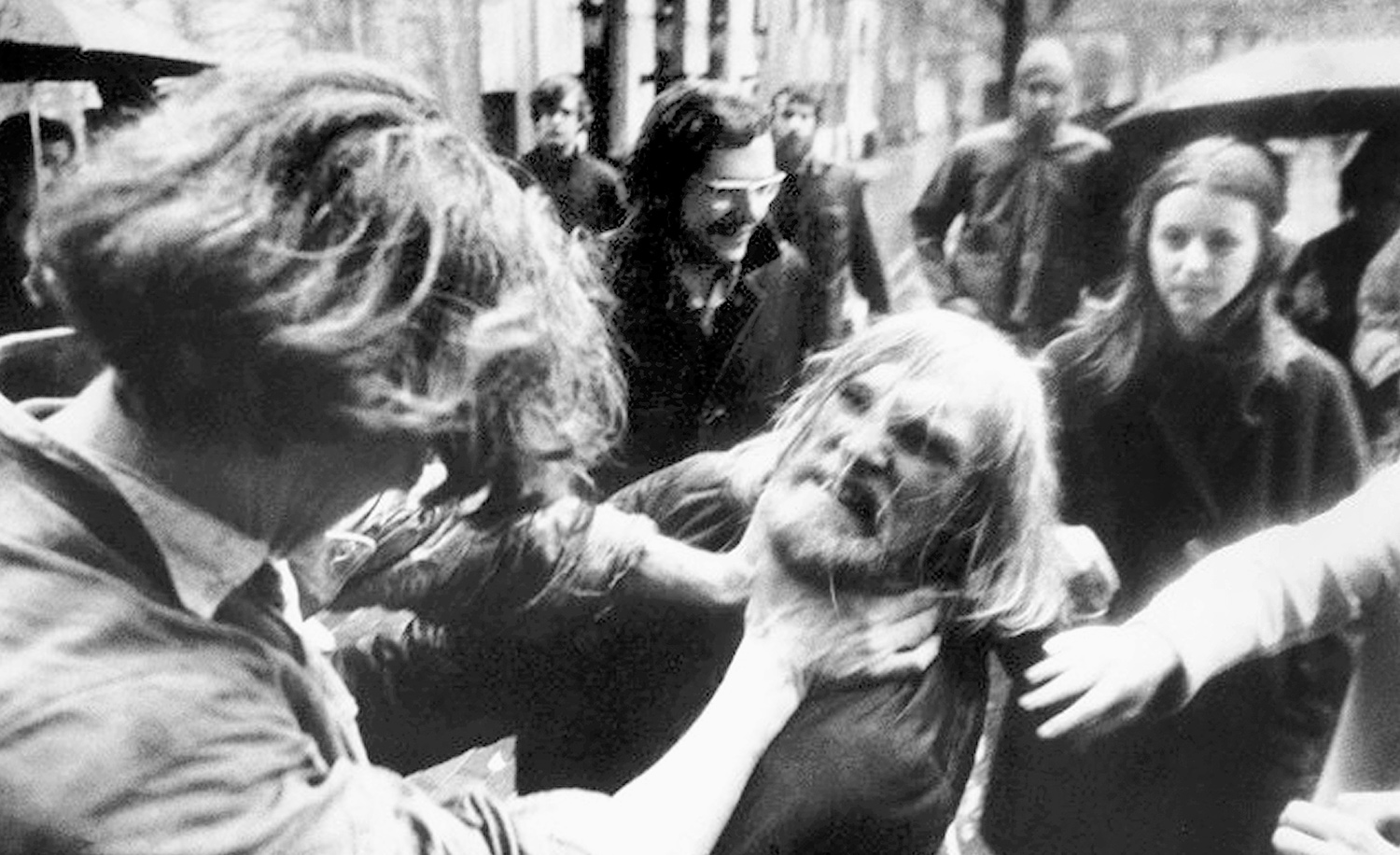

In the late 1960s, appointments in Jewish studies were springing up in tandem with the “adversarial culture.” But we intended to strengthen the universities, not to trash them.

Ruth R. Wisse discovers her husband and her subject.

With the relaxation of Catholic influence in Quebec, local Jewish culture began to come of age and flourish.

We were invited to join in the school’s prayers and hymns, but our grateful acquiescence also implied there was something illicit or shameful about our Jewishness.

And come to differing conclusions about the obligations of collective living.

Father brought us out of bondage, but Mother decided where we were to settle and how we were to live.

It wasn’t easy for an entire Jewish family to escape Eastern Europe in the mid-20th century. Ruth Wisse’s did.