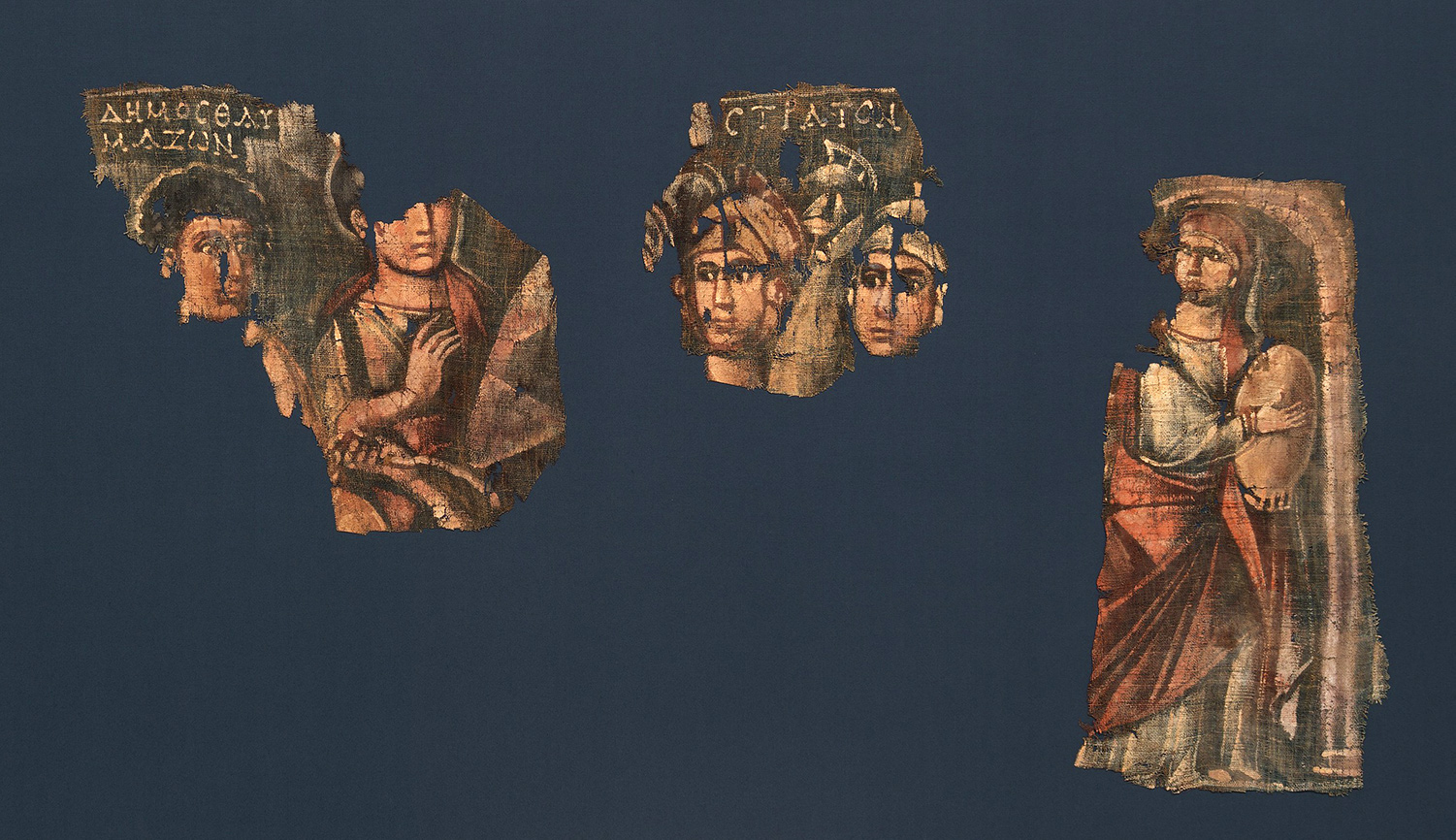

Three elements from a painted hanging depicting the crossing of the Red Sea, mid-2nd–mid-4th century CE. Met Museum.

I am very grateful to Hillel Halkin, Jon Levenson, and Ronna Burger for taking time and trouble, especially in these terrible days, to comment on my essay “The People-Forming Passover,” excerpted (with small modifications) from my forthcoming book, Founding God’s Nation: Reading Exodus. These three vastly different responses remind me again of the truth of Kass’s First Maxim, formulated years ago: what A says about B says much more about A than it does about B. Lest you think I believe myself immune to such projecting distortions, I invite you to keep my maxim in mind as you read my replies.

My friend and fellow octagenarian Hillel Halkin is honest enough to suspect that it is his own unrelieved disappointment in mankind’s folly and wickedness that may lie behind his most peculiar response to my essay. Provoked by my upbeat account (I thank him for praising it) of how God initiates the soon-to-be-liberated Israelite slaves into an elevated way of life aspiring to righteousness and holiness, Halkin is moved—weirdly, in my view—to feel sorry for God. The story of the human race, says Halkin, is one of failure after failure: “We never learn. We never will.”

Halkin is not content with his misanthropic picture of human history. He faults God for the same failure as His creatures: God also never learns, and it seems He never will. The tragedy, says Halkin, is that God’s disappointments in man all come from His foolish optimism, from repeatedly placing too much hope in the educability of human beings.

Strange thought or not, one has to love a man like Halkin whose empathy is capacious enough to feel pity for the Almighty. But not so fast. Pity, says Aristotle, is pain evoked by the sight of undeserved misfortune of the sort that one might expect to suffer himself. Halkin’s pity partakes of the same identification, albeit the direction is backward: imagining that God must have shared his own grand hopes for humankind, Halkin assumes that God must now be suffering terribly along with him.

To be fair, Halkin does not rely solely on projection. He also cites textual evidence. But the evidence, I now argue, need not be interpreted in his way.

Before the call of Abraham, the early chapters of Genesis do indeed show us the uninstructed human alternatives, each of which ends in disaster: simple innocence (the Garden of Eden); life without law (Cain and Abel, and the violence that leads to the Flood); life under the primordial law (Noah unfathered by his son Ham); and the technological and universal secular city (Babel). Halkin’s (not unreasonable) way of speaking about this sequence is to say that God (in sadness) keeps trying new plans after His old ones fail, even being forced in some cases to make concessions to unavoidable human weakness—for example, in granting Noah permission to eat meat after his problematic animal sacrifice (more on this below).

But if the text is not just recording ancient history but telling a story to enlighten its readers, then this sequence of trials and failures becomes a way of showing utopian readers that all of their imaginable alternatives to the world they know have been tried and failed—which is to say, they are terrestrially impossible. We have it on the Highest Authority that the human spirit of righteousness is not strong enough to rule from within, but needs His outside instruction, legislation, and help. God is not “changing” or being “educated”; rather, His sacred story is educating the reader to be prepared to see the necessity of God’s project begun with Abraham, a project in which the reader is invited to become a vicarious participant, never mind a reader whose world is already vastly better than it would have been if God had not first bothered with Israel.

Halkin next cites the ex-slaves’ murmurings in the desert over absent water and food as a sign that they learned nothing from their recent deliverance at the Sea of Reeds. But man cannot live on memories alone. Although Moses is exasperated with the people’s weaknesses, God never blames them for their needs or complaints. Indeed, He is waiting in the wings for the Israelites to demand food from Moses, precisely in order to test, by means of manna, whether they will walk in His Way or not.

For Halkin, the clincher of human faultiness occurs in the episode of the golden calf, as the people, shortly after God’s revelation (containing His condemnation of idolatry), “plunge straight to the depths of depravity, worshipping an animal statue with bacchanalian rites.” To prove that the verdict against the people is not merely his own, Halkin rests his case on God’s speech to Moses: “Now therefore let Me alone that My wrath may wax hot against them, and that I may consume them; and I will make of thee a great nation.” But Halkin quits the text too soon.

No doubt this is a disgraceful moment for the ex-slaves. But God’s threatening remark serves to bring Moses to the people’s defense. Told to “let Me alone,” Moses takes the bait and moves in close. And for the first time ever, he identifies himself with the Israelites: “us” and “we,” not “Your people” or “that people,” as he had always called them before. By granting Moses the reprieve he pleads for, God arranges for the high-minded Moses, who relates freely to God intellect to intellect, to take ownership of the people and to accept their greater neediness, including the need for a physical means of relating to their God. This need is met in the immediate sequel with the building of the Tabernacle, and Moses has to build it for them—and also for Him, to dwell among them.

The episode of the golden calf, shameful though it was, may nonetheless have been necessary. The demands of God’s Law are so great, and the pursuit of perfection so arduous, that failure is almost certainly inevitable. (Although the Decalogue teaches “thou shalt not murder” and “thou shalt not steal,” the ordinances [mishpatim] that follow give instructions about how to treat cases of killers and thieves.) To show the people—and the reader, and sooner rather than later—what happens when the people violate the covenant, we get in the golden calf a tale of the ultimate transgression: idolatry and covenant-annulment. But, thanks again to Moses’ remarkable intervention, we get spectacular and indispensable news.

The people—and we readers—learn that the Lord their God is not only a “man of war” and a good provider. He is also “merciful and gracious, long-suffering, and abundant in goodness and truth; keeping mercy unto the thousandth generation, forgiving iniquity and transgression and sin. . . .” Only when armed with this knowledge can any people accept the daunting call to become a kingdom of priests and a holy nation. Failure, we now know, will be inevitable; but if we show remorse and repentance, there can be forgiveness. Thanks to what we learned about God from sinning gravely, human beings can persist in trying, generation after generation, as the Jewish people have done since Sinai. The world does not demand perfection, but it requires and rewards aspiration to it.

God is not, as Halkin claims, an optimist. Already at Noah’s sacrifice, He recognizes that “the imagination of man’s heart is evil from his youth.” He is rather a God of good hope, His own hope inspiring hope in His people—that the world is the kind of place that answers to our striving to perfect ourselves in the service of God.

The human report card is, to say the least, decidedly mixed. But I cannot read the story of God’s project with the Jewish people as a failure. Quite the reverse. The ancient Mesopotamians, Egyptians, and Canaanites against whom the Way of Israel was forged have disappeared without a trace. So, too, the glorious Greeks and Romans. Yet thanks to the teachings given them in Exodus, and despite all odds, am Yisrael ḥai, the people of Israel lives.

If, under Halkin’s imaginative prodding, we must try to envisage God’s present state of mind (and I never entertain such presumptuous thoughts), I simply refuse to suppose that He is terribly disappointed that one supremely thoughtful Jew, living today in the Third Commonwealth, should be finding fault with His people. Is it not only on the basis of what God taught the Jews and the world at Sinai that Hillel of Zichron Yaakov can make such heartfelt complaints? Before the Exodus from Egypt, no one in the world would have noticed.

Jon D. Levenson, Harvard’s distinguished biblical scholar whose body of work on the Hebrew Bible I greatly respect, has very generous things to say about my contributions to public moral discourse. He also praises isolated insights and formulations of my Exodus chapter—not least because he likes that they fly in the face of contemporary cultural prejudices. But about my overall discussion he has little to say, except to express serious reservations about the wisdom-seeking way I read the Torah.

He not only believes (as, in fact, do I) that it is exceedingly difficult to “extract universal philosophical lessons from the very non-philosophical literature that makes up the Jewish Bible.” But by challenging four of my interpretations (none of them, by the way, central to the main argument and, in my opinion, mainly taken out of context), he also concludes that my attempt to read the Torah in search of wisdom has led me to confuse my own views with the Bible’s:

In Kass’s understanding of “the way of life that the Lord has in store for humankind,” . . . people should also be skeptical and leery of sacrifice, think the message of the wrenching narrative of the Binding of Isaac is that one should not kill one’s child, regard primogeniture as dangerous and against God’s wishes, and believe that the criteria for making outsiders into fully enfranchised insiders should be simple and readily available. Those positions . . . do not reflect the thinking of the Hebrew Bible but rather Leon Kass’s own sense of what is reasonable.

My goodness! Not only do I not recognize myself in these conclusions, but I believe none of the things attributed to me. How—and why—has Levenson made such a mistake? We shall have to review what he considers his evidence.

Before doing so, I want to acknowledge that I am acutely aware of the difficulties confronting any attempt to read the Bible in search of wisdom. In the long Introduction to my forthcoming book, I acknowledge that

the Bible is not a work of philosophy, ordinarily understood—though it is hard to say exactly what kind of work it is. Neither its manner nor its manifest purpose is philosophical. Its entire approach appears to be anti-philosophical. . . . Over centuries, the great sages of the Jewish tradition, deeply steeped in the Bible, read the text—especially the book of Exodus—not as a platform for universal speculation but as a source of law and morals for the Children of Israel. Jerusalem is not Athens.

But I go on to argue that “if there is wisdom in the Hebrew Bible, it should be available not only to Jews and Christians but to all.” Moreover, as I claim, the Bible—note well, not the later exegetical tradition but the text—agrees:

The text provides strong indications that the Lord’s intention for His political founding is not merely parochial. Although He is directly concerned with the Children of Israel, He appears also to have the whole human race in mind. It is as an alternative to the failures of human beings uninstructed that He summons Abraham to initiate His Way for humankind, promising him that “all the families of the earth shall be blessed in you” (Genesis 12:3). He enters into a contest with Pharaoh (the plagues) in order that “the Egyptians shall know that I am the Lord” (Exodus 7:5). He establishes His covenant with Israel, that it might become a “kingdom of priests and a holy nation” (Exodus 19:6), with a people that His prophets will later call “a light unto the nations” (Isaiah 49:6). And when Moses at the end of his life repeats the Law to the Children of Israel as they prepare to enter the Promised Land, he tells them that their statutes and ordinances are “your wisdom and your understanding in the eyes of the peoples: when they hear of these statutes they will say, ‘Surely this great nation is a wise and understanding nation’” (Deuteronomy 4:6). The wisdom of the Torah is said by the Torah to be accessible to everyone, even to those on whom it is not binding.

I also say in the book’s Introduction that I am acutely aware of the danger that

one will find in the text not what the author intended but only what one has put there oneself. For these reasons, a philosophical reading of Exodus must proceed with great modesty and caution, not to say fear and trembling. . . . Moreover, I make no claim to a final or definitive reading. The stories are too rich, too complex, and too deep to be captured fully, once and for all. One can therefore, as I hope to demonstrate, approach the book in a spirit that is simultaneously naïve, philosophical, modest, and reverent.

As to whether I have succeeded in my effort, the proof of the pudding must be in the eating. So let’s look at what has left a bad taste in Levenson’s mouth.

First, what I said about sacrifices. I wrote that “the Torah, at least at the start, is not at all keen on sacrificing,” and I cited as evidence the uninstructed sacrifices of Cain and Noah and God’s reaction to them. Levenson, ignoring my specific qualification “at least at the start,” infers that I have a problem with sacrifices, puts me in a class of other worthy people who are uneasy about sacrifices, and concludes, that “Kass is in good company . . . but not in the company of the Hebrew Bible.”

Because he knows (by the way, so do I) that God eventually commands animal sacrifice on a large scale, Levenson assumes that there can be nothing humanly problematic about it. So he blithely ignores the evidence that calls attention to the problem and thus illuminates why and how the Torah goes about addressing it. It seems never to occur to him to consider that the Bible might, in the examples of Cain and Noah, be offering us insights into the reasons and ways that human beings uninstructed might attempt to be in touch with the divine, and what might be questionable about them. In the case of Cain, he does not wonder what the Bible might be suggesting by presenting the first man born of woman (hence, perhaps, a human paradigm) as a farmer (needing rain), a fratricide, and the founder of the first city—and also the initiator of offerings to the divine. He complacently says that “the narrative treats sacrifice as a known institution and hardly something that someone ‘invented.’” A known institution for a world with only one primordial family?

Whence comes the impulse to offer sacrifice, especially if none has been requested or commanded? Is it merely an innocent desire to give thanks for bounties received, or an anxious inquiry to find out if “anyone” is paying attention to me? Or, as I wrote, might it not stem from other conflicting roots in the human soul:

on the one hand, a Dionysian desire to unite with the primordial chaos, effacing all distinctions and order; on the other hand, an Apollonian desire to celebrate the source and principle of order by appealing to and acknowledging the rule and source of separation. And again, on the one hand, a wish to assert human power against and over the whole by trying to compel (through gifts or bribes) the highest power to do one’s bidding; on the other hand, a wish to nullify one’s own power before the whole by demonstrating our willingness to do the bidding of the highest power.

Which is it that moves Cain? Can we learn about it from the fact that he offers his sacrifice only in the end of days (that is, does not offer the first fruits) and that he gets angry when his offering is not yet accepted? Levenson appears uninterested. Sacrificing is just what people do.

But Levenson’s habit of reading is laid bare in his handling of my remarks about Noah’s uninstructed animal sacrifice, offered as soon as he gets off the ark on which he has been the steward of all life (and all were vegetarian). Levenson is “not persuaded” that, as I claimed, God makes a most negative comment on the animal sacrifice of Noah. In support, he correctly quotes the text—“The Lord smelled the pleasing odor and the Lord said to Himself: ‘Never again will I doom the earth because of man . . .’”—and runs off to buttress this positive interpretation with “a close parallel case” from Numbers where an aromatic sacrificial offering stems a deadly pandemic. But Levenson strangely omits the immediate next words of God’s comment, with its explanatory (and condemnatory) judgment on Noah’s sacrifice: “for the imagination of man’s heart is evil from his youth.” That is not Kass speaking, but the Lord.

From this explicit negative judgment, we might reinterpret the beginning remark to mean that God discerned that the smell of roast meat was pleasing to Noah. Not having been told how to express thanksgiving, Noah gives God a gift on the assumption that God would like what he, Noah, likes. (Recall that the first bird Noah sends forth to find dry land was not the seed-eating dove but the flesh-eating raven.) Even Noah, righteous and simple Noah, the new and better Adam, is not pure at heart and has a taste for blood.

Instead of running to Numbers, Levenson could have found better evidence of God’s verdict on Noah’s sacrifice in the immediate sequel: His response is contained in the Noahide code and covenant. He concedes to human beings the right to eat meat, but not the blood, perhaps in the hope that their bloody-mindedness will be sated by meat and their homicidal tendencies will be curbed.

In the same vein, still following the evolution of the Torah’s treatment of sacrifices, we should wonder why, in Exodus, the Lord tells Moses to build Him an altar only after the people are standoffish and terrorized during His proclamation of the Decalogue. Even more should we wonder whether there is any connection between the orders to build the Tabernacle and their immediate antecedent in Exodus 24: a wild, blood-strewing, uninstructed sacrifice, initiated by Moses in a ceremony to ratify the covenant, followed by an aestheticized vision of the Lord experienced by the elite on the mountain, during which they did eat and drink as if having a picnic. Does not the Tabernacle speak to these impulses, providing a place where they can be expressed but only under God’s measure and rule? What may we not learn from the Book by paying attention to immediate antecedents and consequences, rather than by hopping around to find supporting texts?

Levenson’s second charge concerns the Binding of Isaac, and here I must confess I have myself contributed to misleading him. Back in the same paragraph claiming that, at least at the start, the Torah is not at all keen on sacrificing, I concluded: “Indeed, until now, God had asked only Abraham to bring a sacrifice—and He did so only to teach Abraham that He does not really want child sacrifice but only the father’s dedicated awe and fear of God.” (I emphasize the offending words.) The point I was trying to reinforce was that God, prior to Passover night, had not previously called for and accepted any sacrifice. But this final sentence, alas, was altered in the copyediting stage of my book, and I failed to catch it: it originally said: “But from the experience Abraham learned that God does not. . . .”

Like Levenson, I have written at length about the meaning of the test of Abraham and know that its primary purpose was not to inveigh against child sacrifice but to discover what was first in Abraham’s heart: awe-fear-reverence for God, above all else. I have defended the reasonableness of the test and of Abraham’s deed, not because I like them but because the text has taught me—as God taught Abraham—what He wants from human beings. Since Ronna Burger also takes up this subject, I will defer my fuller answer on the Akeidah to my response to her below.

Trying your patience, permit me also a response to Levenson’s third unwarranted charge: that I misunderstand the Torah’s teaching about primogeniture, which he sees in a positive light—“part of the same conceptual complex” as the consecration of the firstborn. But he misses the point entirely. Where the Torah undercuts giving preference to the firstborn, I contended, it does so because exercising that preference means taking one’s bearings from what nature makes first, instead of what is first in merit or godliness. And I linked this to the Torah’s wholesale attack, beginning with Genesis 1, on worshipping nature and seeking to take cultural guidance from nature’s doings. (Ronna Burger’s response understands me perfectly.)

But Levenson, failing to distinguish between the naturally first in birth from the culturally first in God’s eyes, offers, as his evidence that the Torah loves primogeniture, the very best text for proving the opposite: God’s speech that Moses is to make for Him to Pharaoh: “Israel is My firstborn son. . . . Now I will slay your firstborn son.” The meanings of “firstborn” could not be more opposed: Israel is not the world’s firstborn nation, but is first in God’s love, and only by virtue of God’s election: it is God’s will that confers primacy to Israel, not the accidents of natural birth order. By later claiming the naturally firstborn son for Himself, God is precisely overturning the cultural prejudice that takes nature as the guide for ordering human affairs. The foolishness of doing so was already hinted at in Genesis by giving Rebekah twins and making the son who would become Israel a mere heel short of coming “first.”

Space does not permit an answer to Professor Levenson’s fourth charge, namely, that I have read into the text some universalist idea of the ease of converting to Judaism. Trust me, I have no such view. I was simply astonished to find in the text on Passover night—a night on which a mixed multitude went out with the Hebrews—specific instructions regarding non-Israelite sojourners and how they might partake in future Passover commemorations. If submitting to circumcision—so far the only mark of covenantal membership—did not make the sojourner, as the text says, the same “as one that is born in the land” (Exodus 12:48), then someone should show me the textual evidence to counter the text’s conclusion: “One law shall be to him that is homeborn, and unto the stranger that sojourneth among you” (Exodus 12:49).

Just as Jon Levenson admires those passages where I oppose contemporary cultural prejudices, so he leaps upon those sentences that he fears could lend them support. In this study, however, I am not engaged in cultural criticism, but instead I am trying to understand the book of Exodus as a book, an integrated whole, hoping to learn from it about how Israel became a people, still here, still exemplary, still with something to teach me and the world about how to live. Is this an illegitimate way of reading the Torah?

I fully grant that it is not the way either of traditional Jewish exegesis or of scholarly biblical criticism, in both of which Levenson is deeply learned and wise. And I gladly concede that I am missing a great deal—including about the meaning of the text itself—by reading for meaning without the aid of commentaries or of insights from source criticism. But I know from four decades of living with the text, read line by line but also as a living and coherent work, how much the Bible has shown me about things that matter and, even more, how much it has worked on me and changed who I am—I believe, for the better. I wonder whether academic biblical scholarship produces the same result.

Ronna Burger’s comment fulfills any serious author’s hopes: an engaged, careful, and generous reading, faithful to the spirit and letter of what he has written, and, by grasping the big picture, carrying his thought farther than he did himself. I have read and re-read her response several times, each time seeing more clearly the richness of her train of thought and appreciating the force of her questions. My comments here can be but a down payment on a conversation that I hope I might someday be able to have with her.

Following linguistic echoes and thematic clues, Burger deftly weaves together Exodus passages about male circumcision, the blood-marked doorposts of Israelite houses on Passover night, and the future redemption of the firstborn sons; and she combines them with Genesis stories of the binding of Isaac and Eve’s boastful claims at the birth of Cain—all to very great effect. She detects a connection between the blood of circumcision (in the Bridegroom of Blood episode of Exodus 4) and the blood of the sacrificial lamb with which the Israelites consecrate their houses on Passover night and, by this substitute offering of life, prevent the slaying of their firstborn. Both practices, Burger continues, imply that all children—especially the firstborn, as herald of nature’s procreative power—belong in fact to God.

That idea is made explicit in God’s demand that all the firstborn of Israel, both of man and of beast, shall be sanctified unto Him. Not only are they “owed” for the redemption on Passover night; they are, in truth, also His. True enough, God will allow the human firstborn to be redeemed. But, as Burger poignantly notes, “in the requirement to redeem his firstborn son, every father faces symbolically the dreadful demand issued to Abraham [in the Akedah] and only at the last minute rescinded.” Burger then traces God’s insistence that life is a divine gift to a problem already revealed in the Bible’s first birth, when Eve proudly boasts of her (natural) creative powers. Burger endorses and extends my view that the Bible’s corrective to both human pride and the worship of nature’s power is “the conception of the firstborn as one who belongs first and foremost to God.”

But having seen the matter so clearly, Burger withholds her assent: “Is it really possible, or desirable, simply to deny, let alone surrender, this most intense attachment to one’s own [children]?” My first temptation (I should have resisted it) is to suggest that this is a mother’s question. Mothers unqualifiedly love their own, as they are naturally governed by ties of blood and bearing. Fathers, by nature more detached, are more capable (for worse and for better) of dedicating their sons to all sorts of “gods,” even at risk of their lives.

I am not making this up. Abraham did not tell Sarah that he was taking Isaac to Mount Moriah, and for good reason. According to the Midrash, when she learned after the fact what her husband had done to their son, Sarah dropped dead from horror. Following in Sarah’s footsteps, Burger finds textual grounds (God sends only a messenger to stop Abraham in the fatal act, and He never speaks to him again) to suggest that Abraham actually failed God’s test. Indeed, she wonders whether the entire episode might not be intended as a critique of man’s willingness to give up everything for God.

This reading of the text is hard to sustain. Precisely as a reward for Abraham’s willingness to surrender to the service of God his beloved Isaac (and even God’s promise that His covenant would be transmitted solely through him), the Lord—not the angel— swearing an oath, renews and expands His covenant and His promises of progeny. Also, for the first time, Abraham is told that his seed shall be victorious in wars with its enemies—which means, of course, that there will be later need for God-fearing men to “sacrifice” their sons, this time in battle; in the absence of fathers who are willing to pay such a price, God’s way on earth cannot survive in the world against its enemies. Finally, Abraham is told that all the nations (compare Genesis 12:3, “all the families”) will be blessed in his seed. Why? Because he hearkened, in awe-fear-and-reverence, to the voice of the Lord. Whether we like what Abraham did or not, we have it on the highest authority that Abraham passed the test, summa cum laude.

Father Abraham, as I argue in The Beginning of Wisdom, my book on Genesis,

is the model father, both of his family and of his people—yes, even in his willingness to sacrifice his son—because he reveres God, the source of life and blessing and the teacher of righteousness, more than he loves his own. He is a model not because all fathers should literally seek to imitate him; almost none of us could and, fortunately (as we learn from the story), none of us has to. He is a model, rather, because he sets an admirable example for proper paternal rule, in which the love of one’s own children is put in the service of the right, the good, and the holy. . . . [The true father] will not finally love his son solely because he is his own, but will love most that in his son which is good and which is open to the good, including his son’s own capacity for awe before the divine. In this sense at least, he is ever willing to part with his son as his son, recognizing him—as was Isaac, and as are indeed all children—as a gift, and a blessing, from God.

On a separable matter, Burger observes, almost in passing, a striking difference between Athens and Jerusalem on the subject of fathers and sons. Greek thought, she points out, is dominated by the crime of patricide and the threat of sons to paternal power. Biblical thought is dominated rather by the threat of fratricide, from Cain and Abel onward, down to (as I argue in the Exodus book) Moses and Aaron. She wonders about the reason for the difference, but leaves the question open.

Perhaps the following thoughts can be helpful.

Patricide is the essential crime of the tyrant, a man who aspires to full self-sufficiency, and who therefore rejects his dependence on his source as well as the need for anyone to replace him. Like the pursuit of bodily immortality for oneself, the tyrannical aspiration is in principle hostile not only to fathers but also to children, those who will take one’s place, those who are willy-nilly the “erasers” of their fathers. (Pharaoh is the Bible’s best example.)

In Israel, by contrast, God is the acknowledged father, and the tyrannical temptation to self-sufficiency is tamed both by the obligation to circumcise the sons in memory of the covenant and the recognition that all “sons,” including the father, are children of God. Because the goal in Israel is not personal glory but transmission of God’s Way of life, the temptation is less tyranny and apotheosis than preeminence and mastery over one’s equals. If the political goal of Israel is a society that celebrates the brotherhood of men (each one equally a godlike image of the Creator) under the fatherhood of God, the aspiration to rule is the enemy of equality. Founders are in principle fratricides. The ruler as ruler has no brothers, has no equals. He must be constrained to remain his brother’s keeper.

In her final reflections, Burger muses on the changing role of Moses, from self-effacing executor of God’s orders to virtually independent leader and founder. (She does not mention the topic of fratricide or Moses’ relation to brother Aaron; I do so in the book.) And she closes by opening the enormously complicated question of the relation between human agency and the power of God.

The formulation of that question, I hasten to point out, comes from philosophy and is foreign to the language or concerns of the Torah. Still, the text in many places offers us numerous occasions to ponder the subject.

What is the difference between Pharaoh’s strengthening his own heart and God’s strengthening it? During the victory in the battle against Amalek, the name of God is not mentioned, but does that mean He was “absent”? What is really going on when Moses raises his hands? And again, Moses lives with a Voice in his head that no one else hears: how does his “human agency” therefore differ from that of other men, who either hear nothing or, instead, answer to other “callings”—be they of wealth, honor, or pleasure? What is inspiration, and what is a call—and why do some people answer? Can we really say what is human—and what is perhaps more than human—in so-called human agency? What is the true meaning of “God helps those who help (Him help) themselves?” To my mind, an awe-inspiring mystery.

Moses does indeed grow in power and independence from the time he first takes the job. Indeed, a number of the Lord’s deeds are explicitly intended to increase the people’s trust in him. A major purpose of the extravaganza on Mount Sinai, says the Lord, is to make the people believe in Moses forever (Exodus 19:9). Once he acquires “ownership” of the people after the golden calf, Moses becomes the indispensable man, leading the people for 40 years in the wilderness, right up to their entrance into the Promised Land. Yet unlike Aaron, who despite his role in the episode of the golden calf gives rise to the priestly line that will serve forever, Moses’ magnificent deeds are one and done. In the end, the genius of Moses, God’s lawgiving prophet, disappears from the scene. In its place is God’s Law and the Tabernacle, both now in human hands.

What shall we say about the enduring power of that Law? Is it a tribute to Moses’ greatness or, instead, to God’s? Must we really choose?