The essay below is adapted from Founding God’s Nation: Reading Exodus by Leon R. Kass, forthcoming from Yale University Press in January 2021.

The biblical book of Exodus, writes Kass in his Introduction, “not only recounts the founding of the Israelite nation, one of the world’s oldest and most consequential peoples, . . . but also sheds light on enduring questions about nation building and peoplehood.” His scintillating, profound, and meticulously close reading of Exodus, “one of humankind’s most important texts,” masterfully draws out, line by line and chapter by chapter, its enduring moral, philosophical, and political significance for its time and ours.

In our excerpted essay, Kass focuses on the events of the night before and the morning of the Israelites’ departure from Egypt—the events rehearsed each year at the Passover table—and on their significance in the formation of the Jewish people and nation. Its appearance here follows by almost seven years the first monthly essay in the then-newly founded Mosaic:“The Ten Commandments: Why the Decalogue Matters,” by Leon R. Kass (June 2013). As we took pride in publishing that early taste of a larger study-in-progress, we take pride in presenting this offering from the now-completed work.

—The Editors

In chapter 12 of the book of Exodus, the long-awaited deliverance of the Children of Israel from their centuries of bondage in Egypt is finally at hand. But, for its own good reasons, the Torah does not go straight to the event.

Instead, the departure from Egypt, to be accomplished in consequence of the tenth and final plague—the death of Egypt’s firstborn—is preceded among the Children of Israel first by the communal enactment of a ritual sacrifice and meal and then by clear instructions regarding a special commemorative practice that the Israelites must follow in the future, indeed forever: the annual seven-day festival of Passover.

The one-time enactment is a modest (yet impressive) people-forming event, as each family declares its willingness to be delivered by killing a lamb, marking the doorposts of the house with its blood, and eating the prescribed meal of fire-roasted lamb, flatbread (matzah), and bitter herbs. The annual commemorative practice will be an elaborate people-renewing event, as each family relives the deliverance by telling its story and by re-creating the festive meal. Later on, post-deliverance, the commandment about the annual celebrations of Passover will be supplemented by another commemorative practice of redeeming firstborn sons (and sacrificing firstborn animals).

The commandment to celebrate Passover, the first national Israelite law, honors the first step in the Children of Israel’s becoming the people Israel: their deliverance by the Lord, as the Lord’s people, from the land of Egypt and the house of bondage. On the eve of their redemption, and for seven days annually thereafter, the Israelites are to remember, reenact, and celebrate—family by family, yet all at the same time and in the same way—their emergence as a united community, independent and out of Egypt, and grateful to the Lord Who delivered them.

If that is the big picture of what the text is up to, why does it not proceed directly to the main action? I have two suggestions.

To this point, the contest with Pharaoh has remained inconclusive. By now, we readers of the story may well suspect, as Pharaoh does not, that the decisive conclusion will soon be upon him. But while we await the finale, the text teaches us, as the Lord teaches the Children of Israel, that there is more at stake than getting the slaves out of Egypt.

In framing the actual Exodus by these first Israelite laws, the Torah clearly hints that the essence of the story lies not in mere (political) liberation from bondage but in liberation for a (more than political) way of life in relation to the Liberator. In this perspective, getting the Israelites physically out of Egypt is the easy part; much harder will be getting Egypt—both the Israelites’ slavish mentality and the abiding allure of Egyptian luxury and mores—out of their psyches. The first national laws thus give them and us a foretaste of what should replace Egypt in their souls. Even while still in Egypt, they are being primed for Sinai.

Second, until now the Israelite slaves have been almost entirely passive. They have cried out from their miseries. They have turned a deaf ear to Moses’s promise of divine redemption. They have watched from a distance the destructive effects of the plagues on their Egyptian masters. But they have done nothing to show that they deserve emancipation or even that they want to be redeemed.

If they are to make the transition from slavery toward the possibility of self-rule, the people themselves must do something to earn their redemption. The tasks they are given, both before and after their deliverance, are intended in part to make them worthy of being liberated: they are to act, and they are to act in obedience to God’s instructions; they are to act trusting in God and in His servant Moses.

Obedience as the ticket to liberation seems paradoxical. But in fact the text never speaks of the deliverance of Israel from Egypt in terms of freedom. The Torah’s Hebrew words for liberty, d’ror and ḥofesh, do not even occur. To be sure, the Israelites will be politically free from the house of bondage, in that they will not be slaves to Pharaoh in Egypt. And they will have the power and opportunity to exercise choice. What they eventually will be invited to choose, however, will not be “freedom” but something else: righteousness and holiness, gained through willing obedience.

I. What to Expect From Exodus

If these are the goals of the prescribed rituals, the details of each reveal that there is even more going on. The contents of the ritual enactments are multiply meaningful. They convey teachings and inspire attitudes that will embody the way of life for the sake of which Israel is to be constituted as the Lord’s people. They simultaneously speak to the now-rejected way of life represented by Egypt. And they address those permanently dangerous aspects of the human soul that, when unchecked, gain disastrous expression (in Egypt and elsewhere) but, when regulated, carry the marks of God’s Way for humankind.

This last suggestion requires some explanation. As I tried to show in The Beginning of Wisdom, my book on Genesis, the seemingly historical stories at the very beginning of the Torah, before the call to Abraham, are also vehicles for conveying the timeless psychic and social roots of human life in all of their moral ambiguity. Adam and Eve are not just the first but also the paradigmatic man and woman. Cain and Abel are paradigmatic brothers. Babel is the quintessential city. By means of such stories, Genesis shows us not so much “what happened” as “what always happens” in the absence of moral and political instruction.

Although God’s Way, initiated with Abraham, begins to address some of man’s dangerous tendencies, several of these—such as sibling rivalry to the point of fratricide—plague each generation of the patriarchs. As a result, the reader coming upon Exodus hopes and expects that God’s plan for humankind—a plan to be carried forward by His chosen people, Israel—will directly address the evils that naturally lurk in the hearts of men.

Not accidentally, therefore, the substance of the rituals and laws framing the Exodus from Egypt will address such fundamental and highly problematic human matters as how we relate to the divine, how we relate to the rest of living nature, and how we relate to our mortality and our future—or, in the biblical context, to sacrificing, eating, and procreating.

The impulse to sacrifice has deep but conflicting roots in the human soul: on the one hand, the wish to control the powers-that-be by bribing them to do our bidding; on the other hand, the impulse to surrender to the powers-that-be by acts of violent self-abnegation. Many peoples in the ancient world practiced animal sacrifice, even child sacrifice. But the Torah, at least at the start, is not at all keen on sacrificing, which it regards as a problematic human invention. The voluntary offerings of Cain and Noah God neither requests nor even seems to want: He rejects the sacrifice of Cain (the inventor of sacrifices), and He makes a most negative comment on the animal sacrifice of Noah. Indeed, until now, God had asked only Abraham to bring a sacrifice—and He did so only to teach Abraham that He does not really want child sacrifice but only the father’s dedicated awe and fear of God.

Eating, though necessary to all animal and human life, is also problematic: to sustain life and form, eating destroys the life and form of others. The problem is especially severe in the human animal. Voracity, an emblem of man’s potentially tyrannical posture toward the world, extends all the way to cannibalism, just as the impulse to sacrifice can extend also to human—and child—sacrifice.

Finally, regarding procreation, life’s answer to mortality, the firstborn son—as herald and emblem of the next generation—represents both the strength of the father, extending his potency beyond the grave, and a threat to the father’s power, a living proof of his mortality and limited influence. Although fathers take pride in their paternity, they and their sons often struggle for supremacy. We remember Ham’s act of metaphorical patricide against his drunken father Noah, and Noah’s retaliatory curse of Ham’s son Canaan; Reuben’s sleeping with his father Jacob’s concubine; Pharaoh’s ambivalent relation to and desire to control childbirth, and not only among the Israelites.

In all of these fundamental aspects of human life, absent the coming of moral instruction and law, there is the possibility—indeed the likelihood—of two extremely dangerous and wrong-headed tendencies. On the one hand, there is the danger of imposing human reason and will on the world through manipulating sacrifices to the gods, through omnivorous transformation of nature (as food), and through the denial of procreation. On the other hand, there is the danger of surrendering human reason and will to wildness and chaos.

The way of life that the Lord has in store for humankind addresses both of these dangerous tendencies. Human life will be rationally ordered, but the order will not be man-made; it will not be willful, but reasonable. At the same time, the wilder and chaotic passions will be given room for expression, but within measure and under ritualized constraint.

Our animals, the produce of the earth, and the fruit of the human womb will be recognized as ours, but ours no thanks to us. Rather, they embody and reflect an ordered world that we did not make and from which we profit largely as receivers of blessings. Against the luxurious ways of Egypt, the way of Israel begins with modest and restrained animal sacrifice—animal, not human, and no more than can be eaten—with removal of the blood, the essence of life, used instead to consecrate the entire household in dedication to the Lord’s command. The flatbread or matzah—modest, simple, uncorrupted human food, made afresh each time as “mortal” bread and not transformed by human artfulness—limits appetites, moderates our belief in our permanence and our conceit of self-sufficiency, and reminds us that the bread of the earth, no less than the deliverance soon to be procured, is a blessing, not a solely human achievement.

Under the new way, the firstborn, including the human firstborn, will be seen as belonging to the Lord, not to nature or to our prideful selves—neither those who celebrate male potency nor those who celebrate maternal creativity in the opening of the womb. Yet the way of Israel eschews sacrificing the human firstborn, insisting squarely on reclaiming him from the Lord by an act of redemption. It is a repetition of the teaching of the binding of Isaac: God does not want child sacrifice, nor does He want His people to wish to sacrifice their children. He wants them to be dedicated to rearing their children in His ways.

Indeed, the practice of redeeming the firstborn commemorates not only the spared firstborns of Israel but (perhaps) also the humanity of the lost sons of Egypt. Those Egyptian children may have been justly taken as punishment for Pharaoh’s misdeeds and intransigence, and their deaths may have been necessary for Israel’s deliverance and for Egypt’s recognition that “I am the Lord.” But there is pathos, not to say iniquity, in this massive destruction of life, some of it surely guiltless: it is a fact that requires of Israel not so much atonement as acknowledgment. The Israelite lives that were saved and delivered, like the Egyptian lives that were destroyed, hang by a thread. Only by God’s grace—and not solely for our own merit—do we ourselves still dangle.

Keeping this synoptic overview in mind, we turn to the text.

II. Preparing to Leave: Calendar, Passover Sacrifice, and Meal

Their own work with Pharaoh having been completed with their warning him of the tenth plague, Moses and Aaron must now return to the Israelites to prepare them for deliverance. Their orders come immediately in the form of the Lord’s detailed instructions. Spanning twenty verses of uninterrupted speech, they are sometimes surprising, especially at the beginning:

And the Lord spoke unto Moses and Aaron in the land of Egypt, saying: This month shall be unto you the beginning of months; it shall be the first month of the year to you. (12:1-2; emphasis added)

Before the Lord gives any orders about what the people must do, He declares in advance a change in the calendar: a new age is dawning for you, and this month, the spring month of Aviv, which launches your long-awaited destiny, shall be forever reckoned as the beginning of your calendar year. Time in Israel will have a new basis and a new meaning. With sun worship defeated and left behind in Egypt, Israel’s calendar will no longer be based on the sun’s (imagined) revolutions in the heavens or the correlated seasons of the year and the earthly sproutings and harvests they provide.

This seemingly unprecedented innovation completes the Bible’s quiet but insistent polemic against living in thrall to the sun, the moon, and the stars—and the earth. The very beginning of Genesis had demoted the sun to a mere marker for the preexisting day and for seasons. Instead, it instituted a regular weekly seventh day, the Sabbath, independent of lunar change and commemorating instead the Creation and its Creator. Similarly, here, the annual calendar is redefined in commemoration of a historical rather than a natural event. The target is no longer Babylonian “moon time” but Egyptian “sun-and earth” time.

That is not all. At precisely the time of year when there is the greatest reason to celebrate nature, we get instead a celebration of God’s beneficent action on behalf of His people. Aviv is made the first month not because it is the time of renewed sprouting and growth but because it is the month of Israelite deliverance and the beginning of progressive history. To put it another way, the month that is for everyone else the time of nature’s springing forth will be for Israel the time of the people’s “sprouting,” resulting not from natural necessity but from divine choice and deliberate intervention. This change in the calendar is not merely symbolic. The first step to freedom and dignity is to live not on nature’s time but on your own.

The Lord next gives Moses and Aaron orders to transmit to the people. They begin with instructions for a communal sacrifice:

Speak you unto all the congregation of Israel, saying: in the tenth day of this month they shall take to them every man a lamb, according to their fathers’ houses, a lamb for a household; and if the household be too little for a lamb, then shall he and his neighbor next unto his house take one according to the number of the souls; according to every man’s eating you shall make your count for the lamb. Your lamb shall be without blemish, a male of the first year; you shall take it from the sheep, or from the goats; and you shall keep it unto the fourteenth day of the same month; and the whole assembly of the congregation of Israel shall kill it at dusk. (12:3-6)

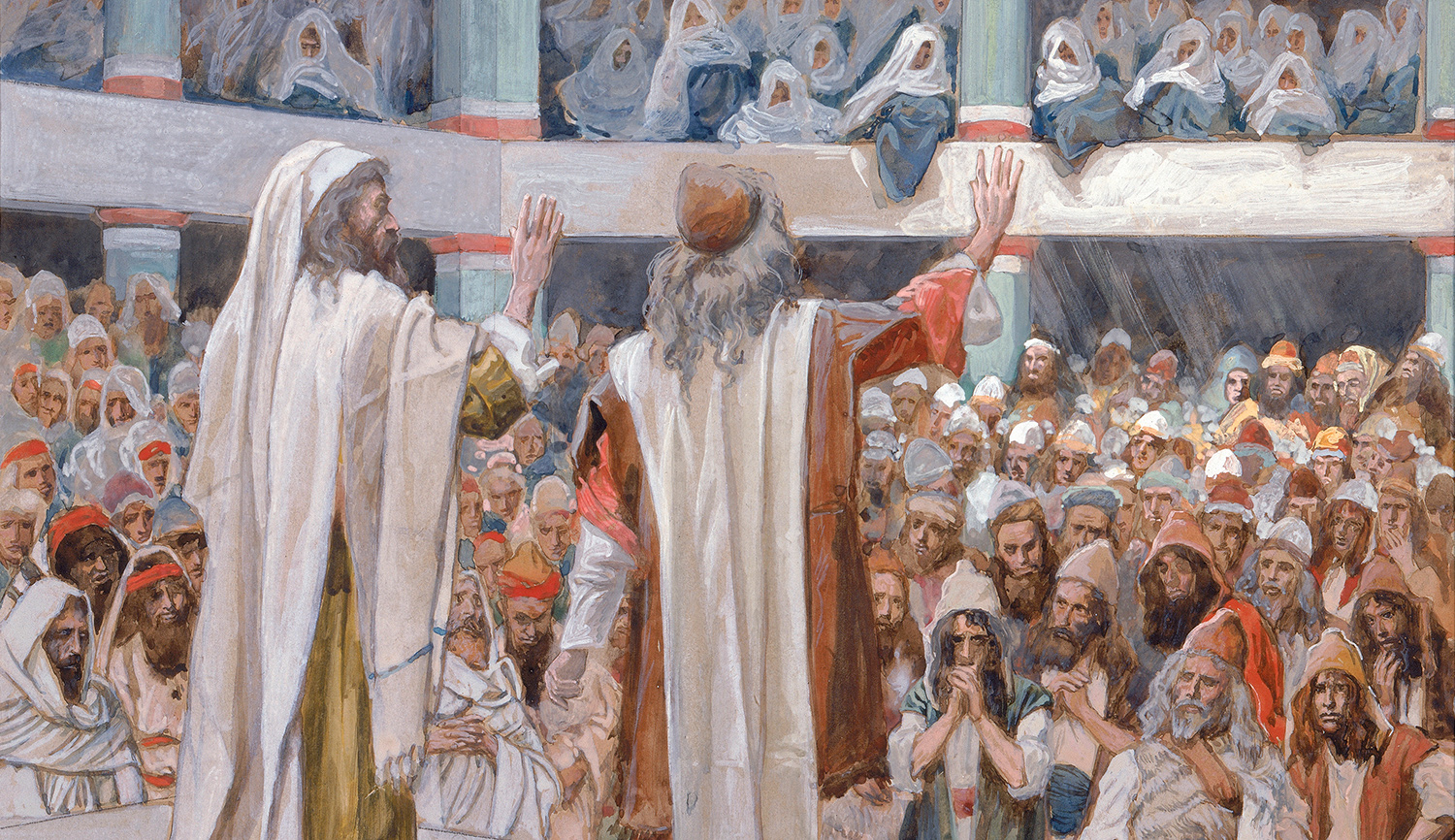

In His striking beginning, the Lord refers to the Israelites for the very first time as the congregation of Israel (not as the Children of Israel)—using the term eydah, “a group fixed by appointment or agreement” (from ya‘ad, “to fix upon”). He continues by describing the common obligation that will earn them this new designation: by special appointment, all of the Israelites, household by household, will at the same time (the tenth day of the month and year just beginning) select an unblemished lamb or kid to sacrifice unto the Lord. And at dusk of the fourteenth day the whole assembly of Israel shall kill the lambs together.

Not since they first cried out in complaint against their servitude (2:23) have the Israelites done anything together. What they are asked to do here will be their first positive people-forming event: an event comprising sacrifice, eating, and blood, each element of which holds great significance. The planning for this event itself builds a community of freedom, for only free people are able to plan for themselves in advance.

The killing of the lamb is to take place on the night of the fourteenth day of the new month: the night of the full moon, called Shabbatu by the Babylonians and regarded by them and other ancient Near Eastern cultures as a night of dread, bad luck, and evil. But in Israel, the night of this full moon will be the blessed night on which the people will “vote with blood” for their deliverance. The Lord, having given the instructions, will briefly “withdraw” from view so that the congregation of Israel can assemble themselves as an identifiable and united community, as the whole assembly of the congregation of Israel. What they have to do, they will not do in secret; thanks to the moonlight, the Egyptians may see them, even as they sacrifice animals that the Egyptians hold sacred.

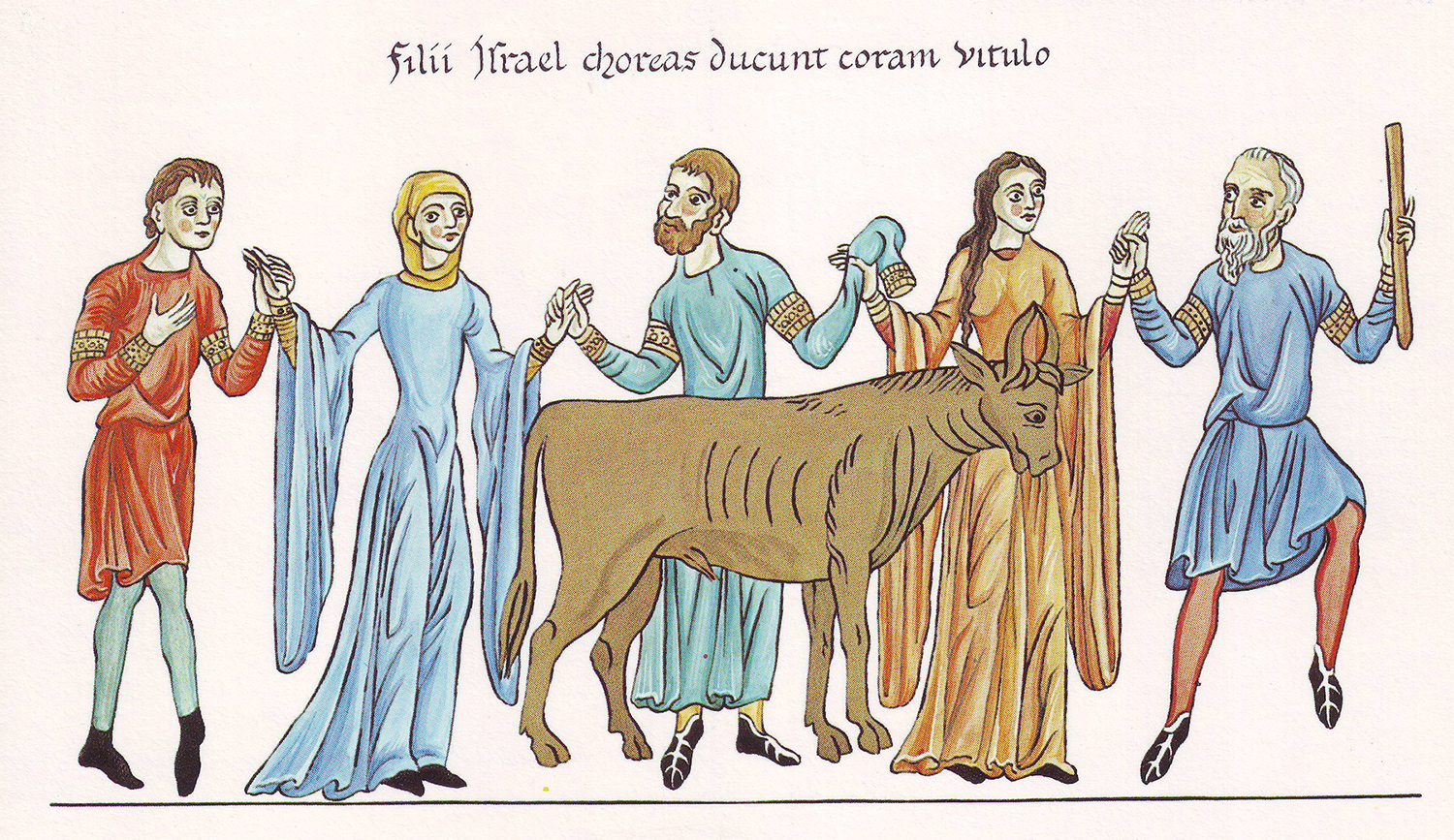

This is no small matter. During the New Kingdom (1550–1070 BCE), the ram was the sacred animal of two Egyptian gods: Amun the king of the gods, who was syncretized with the sun god as Amun-Ra, and Khnum, the god who made human beings on the potter’s wheel. Sacrificing lambs would thus be offensive to the Egyptians and a danger to the Israelites. But, danger aside, as a symbolic gesture the killing of the lamb represents the active entrance of the hitherto passive people into the battle against Egypt and its gods. Their deed here foreshadows their willingness—which will not come easily to them—to take responsibility for themselves and not rely exclusively on Moses and God.

Although the sacrifice is to be performed by the whole congregation of Israel, we should not overlook its household-by-household character. The importance of this arrangement is highlighted by the recurrent mention of bayit, house or household, which occurs four times in these four verses and will occur eleven more times in this chapter of Exodus.

There are several reasons for this emphasis, both positive and negative. In rejection of their situation in Egypt, where their families were threatened by crushing toil and the policy of infanticide, the Israelites, even before their liberation, will reaffirm the importance of family life. Israel will be a nation born of households (not, for example, of isolated individuals entering into a proto-Lockean social contract). Although God is authoring a political revolution, unlike most revolutions this one will be family-affirming rather than family-denying: the attachment to the community and to the Lord will not require renouncing the love of one’s own flesh and blood.

On the contrary, the family in Israel will remain the core of society and will have the educative function of transmitting the covenantal way of life. Far from aspiring only to feather their own nests, in Israel all families will be devoted to something beyond family. Moreover, that higher devotion will enable families to be partners rather than rivals to each other: small households are told to reach out to one another, to make sure that everyone is able to eat, and to eat (only) to satiation, without excess, spoilage, or waste.

At the same time, the household principle is being subordinated to the communal principle and to divine service, in part to acknowledge and remedy the evils that (naturally) lurk in the uninstructed human family: the dangers of patricide, infanticide, and especially fratricide. Thus the familial offering tacitly acknowledges the impulse within families to bloody their own nest, an impulse that must and will be redirected and tamed. (Recall, in Genesis, the Noahide permission to eat meat—but not the blood—in order to avoid homicide, or the substitution of the ram for Isaac in the story of his binding.) It may also serve as belated, symbolic penance for the intended fratricide that brought Israel into Egypt in the first place: the story of Joseph and his murderous brothers, who brought his coat, stained with the blood of a goat, to their father Jacob as (phony) evidence that a wild beast must have devoured him.

The Lord continues with instructions about what should be done with the killed lamb:

And they shall take of the blood, and put it on the two side posts and on the lintel, upon the houses wherein they shall eat it. And they shall eat the flesh in that night, roast with fire, and unleavened bread; with bitter herbs they shall eat it. Eat not of it raw, nor sodden at all with water, but roast with fire; its head with its legs and with the inwards thereof. And you shall let nothing of it remain until the morning; but that which remains of it until the morning you shall burn with fire. And thus shall you eat it: with your loins girded, your shoes on your feet, and your staff in your hand; and you shall eat it in haste—it is the Lord’s passover [pesaḥ]. For I will go through the land of Egypt in that night, and will smite all the firstborn in the land of Egypt, both man and beast; and against all the gods of Egypt I will execute judgments: I am the Lord. And the blood shall be to you for a token upon the houses where you are; and when I see the blood, I will pass over you, and there shall be no plague upon you to destroy you, when I smite the land of Egypt.” (12:7-13)

The instructions begin with a directive about the blood and end with an account of its function: the houses whose doorposts are marked with blood will be spared the devastation of the Lord’s final plague, the slaying of the firstborn. But the marking of the doors has additional significance, as does the use of blood for this purpose.

Did the Lord really need a marked door to tell an Israelite home from an Egyptian? Not likely. The exercise is for the Israelites, not for Him. Each Israelite household must earn its deliverance. Painting one’s door was a freely chosen vote—in broad moonlight—for one’s own redemption, an act at once obedient and faithful, as well as courageous and dignified. It was, to exaggerate but slightly, an act of liberation preceding actual deliverance.

Every Israelite household had a free choice to make. Those who made it in accord with God’s directive, trusting His promise of deliverance, were not only worthy of redemption but were also already partly free of Egypt, where one’s lot in the world was given, not chosen. Those who did not mark their doors, we never hear of. If there were any such, they presumably suffered the same fate as the Egyptians.

And why mark the doorposts with blood? Blood, which the ancient world widely regarded as “the life,” was in some cultures eaten or drunk, often as part of wild cultic practices, as a way of augmenting one’s own powers or communing with the gods. In other cultures, precisely because blood is “the life,” it was more than a physical liquid; it had metaphysical power and could redress the cosmic balance in mankind’s favor. Putting blood on the door would, in those cultures, be a way of warding off evil forces—not by magic but by re-balancing or appeasing the powers-that-be.

In stark contrast, this Israelite use of blood rejects—or, rather, transforms—those ideas and practices, even as it serves to protect the house. When used as God commands, it expresses a personal dedication to a known and benevolent deity and, especially, a trust in His promise of deliverance. “The life” is symbolically returned to its source or owner in a gesture of sacrifice that simultaneously consecrates the house. In addition, Israelite life is surrendered into God’s care and protection through this symbolic substitute for firstborn sons who will not be taken by the Lord from their blood-marked houses. (The Paschal lamb may have a better claim to being such a symbolic substitute.) At the same time, the blood may betoken a willingness to dedicate the sons of the house to the Lord, and even to shed their blood—and the blood of others—in His defense.

God’s central instructions concern the Paschal meal, whose main points have already been anticipated. The meal comprises (1) flesh, the food that (like blood) answers to the animal-like wildness and violence of the human soul, and (2) bread, the so-called human food, which bespeaks man’s rational power to transform external nature for human use (by planting, harvesting, threshing, and grinding grain into flour and by baking moistened flour into bread) and to tame his own appetites through delayed gratification (toiling to sow today what he cannot enjoy for months).

The meal enjoined by the Lord is to be simple, only modestly embellished by culinary art. The meat is to be eaten not raw and not boiled or sauced as a delicacy but fire-roasted and consumed that night in its entirety. The modest bread is not to be leavened; it is the pure and plainest staff of life. Accompanying the meat and flatbread are bitter herbs, a reminder of the bitterness of the slaves’ hard service in mortar and brick (1:12). Taken all in all, it is a meal that meets necessity and rejects Egyptian delicacy and luxury. The frugal meal before the Exodus is meant, among other things, to teach the Israelites to leave their Egyptian appetites behind.

The same teaching of “leaving behind” is underlined by the manner in which the Paschal lamb is to be eaten: ready for departure, with loins girded, shoes on feet, staff in hand, in haste. The anti-Egyptian meal is to be eaten, so to speak, halfway out the door and not looking back.

But the point is not only to be anti-Egypt. Once again, God undertakes to reconfigure the Israelites’ experience of time. Please understand, He implicitly says to them: this is not your ordinary meal, enjoyed in ordinary times. In fact, this is not your time at all: something much more momentous is taking place, something that will change the time of your lives and that of the entire world. Get ready. Get set. It is time to go into a new, forward-looking age.

The instructions conclude with a summary and explanation of their significance: “It is the Lord’s Passover” (12:11; emphasis added). This expression seems to imply familiarity with some preexisting (presumably Egyptian and naturalistic) festival of passover, which, like the sabbath and the calendar, here receives a completely different meaning: it is the occasion of sparing—passing over—the houses of the Israelites when the Lord crosses through the land of Egypt smiting all the firstborn of man and beast and executing “judgment against all the gods of Egypt; [for] I am the Lord” (12:12).

It is easy to see how the execution of this tenth plague will be a catastrophe for Egypt and a fitting punishment for Egypt’s abuses of Israel, the Lord’s “firstborn.” But how, exactly, does smiting the firstborn of man and beast constitute judgment against all the gods of Egypt?

To begin with, we note that the firstborn has a meaning beyond the birth order. The firstborn is the representative of the whole class, a representative promoted by none other than nature herself. Second, all the so-called gods of the Egyptians had their sacred animal or animal emblem. To attack the firstborn of every animal is to hit the representative emblem of the Egyptian pantheon. The Egyptian “gods” are thus humiliated and exposed as powerless or indifferent, incapable of fulfilling their most essential duty: protecting the people who worship them. In this sense too, the tenth plague constitutes judgment against the gods of the Egyptians.

But there is more. To attack the firstborn is to attack taking direction from nature, which alone determines birth order. Bestowing social and political significance on birth order and the firstborn—for example, through primogeniture—is in effect living in deference to nature (not to say necessity or chance). To kill the firstborn is thus a more than symbolic way of overthrowing the widespread human tendency to regard nature as primary and authoritative—which is to say, worthy of reverence or “divine.”

With this reference to the gods of Egypt—the only one in the entire Egypt narrative—we have it confirmed from the Highest Authority that the contest with Egypt has ultimately been about the divine. When the Lord reveals His solicitude for His people, His keeping His word, and His utterly supernatural ability to distinguish not only Israel from Egypt but also, within each household, the firstborn from the rest, the so-called gods of Egypt—including Pharaoh himself—are exposed as nonentities. What “god” worshipped in Egypt can do all that?

III. From One Night to Every Year

In the remarkable next directive, issued without a pause or transition, the Lord moves from instructions for this one night to instructions for its annual commemoration.

And this day shall be unto you for a memorial, and you shall keep it a feast to the Lord; throughout your generations you shall keep it a feast by an ordinance forever. Seven days shall you eat flatbread; surely, the first day you shall put away leaven out of your houses; for whosoever eats leavened bread from the first day until the seventh day, that soul shall be cut off from Israel. And in the first day there shall be to you a holy convocation, and in the seventh day a holy convocation; no manner of work shall be done in them, save that which every man must eat, that only may be done by you. And you shall observe the Feast of Flatbread; for in this selfsame day have I brought your hosts out of the land of Egypt; therefore shall you observe this day throughout your generations by an ordinance forever. In the first month, on the fourteenth day of the month at evening, you shall eat flatbread, until the one and twentieth day of the month at evening. Seven days shall there be no leaven found in your houses; for whosoever eats that which is leavened, that soul shall be cut off from the congregation of Israel, whether he be a sojourner, or one that is born in the land. You shall eat nothing leavened; in all your habitations shall you eat flatbread. (12:14-20)

In a directive probably unmatched in human affairs either before or since, a fledgling people—a mere mass of oppressed slaves—are told, even before it happens, how to celebrate forever the event of their (not-yet) deliverance. The reason is to educate the Israelites about how they are to regard time in the world and themselves in relation to it. The Children of Israel must leave Egypt already thinking about their own children and their children’s children, indeed, about their generations forever. Just as God is taking away Pharaoh’s future, He teaches the Israelites how to think about theirs: an unlimited future informed by memory of their God-delivered past.

The heart of the seven-day memorial is a feast, ḥag, a word that comes to be synonymous with festival. Passover will be the only holiday in Israel’s liturgical calendar for which a ritual meal is biblically prescribed and in which specific foods are designated as obligatory. Unlike the meal on the original night of Passover, the annual Passover feast, as noted, emphasizes the obligation to eat flatbread. The bread of protracted affliction, turned by the Lord’s hand into the bread of hasty exit and instant deliverance, embodies the essence of what needs to be remembered.

Almost equal emphasis, however, is given to what is not to be eaten, indeed not even to be found in the house. In place of the blood-marked doors, there are to be leaven-free houses; twice we are told that anyone who eats leavened (read: Egyptian) bread during the seven days of Passover will have his soul cut off from his people—a fate analogous to that suffered by those Israelites who failed to mark their doors and consecrate their houses. All tokens of Egyptian indulgence, fermentation, and superfluity are to be banished. Those who refuse to banish them will themselves be banished: nay, will banish themselves. By clinging to the ways of Egypt, they effectively excommunicate themselves.

Armed with these instructions about the future observance of Passover, the Children of Israel receive their deliverance on condition that it be understood as a forward-going enterprise in which their chief task is to be mediators. Gratitude and recompense for their deliverance must be expressed by undertaking the tasks of instruction of and transmission to future generations.

What they are to transmit is at this point almost completely unknown, but their orientation in the world has been established in advance. Their obligation to commemorate and reenact the people-forming act of their deliverance by the Lord stands as the keynote teaching. And when Moses, after receiving these instructions, delivers them to the elders of the people, he makes the point explicit:

And you shall observe this thing for an ordinance to you and your sons forever. And it shall come to pass, when you come to the land that the Lord will give you, according as He has promised, that you shall keep this service. And it shall come to pass, when your children shall say unto you, “What mean you by this service?” that you shall say: “It is the service of the Lord’s Passover, for that He passed over the houses of the Children of Israel in Egypt, when He smote the Egyptians and delivered our houses.” (12:24-27)

In calling for the elders of Israel and giving them a condensed version of what the Lord told him to say, Moses is eager to renew relationships, confident that he and the Lord will deliver on their promises and the elders can help get the message across. In speaking with them, he adds specific instructions on how to get the blood on the doorposts and lintel (with a bunch of hyssop, dipped into the basin of blood), directs them not to leave their houses until morning, and tells them why: “For the Lord will cross through to smite the Egyptians; and when He sees the blood . . . the Lord will pass over the door, and will not suffer the destroyer to come into your houses to smite you” (12:23).

Moses concludes by informing the elders of the ordinance about Passover to be observed by “you and your sons forever,” finishing with the lines just quoted: “for that He passed over the houses of the Children of Israel in Egypt, when he smote the Egyptians and delivered our houses” (12:27). In speaking to the people, Moses leaves himself and his deeds entirely out of the account (just as he is missing from the Haggadah, the text read at the Passover seder). For the future people of Israel, the first nine plagues—performed through the agency of Moses and Aaron—do not count. All that matters is the Lord’s mighty hand, taking them out Himself.

IV. Enter the Children of Israel

And now we hear at long last from the Children of Israel. When, before the contest with Pharaoh, Moses came to them bearing the Lord’s new promise, they had refused to hearken to his words, “for impatience of spirit and for cruel bondage” (6:9). This time it’s a wholly different story. When Moses finishes, without saying a word, “the people bowed their heads and prostrated themselves. Then the Children of Israel went and did as the Lord had commanded Moses and Aaron; thus they did.” (12:27-28)

The nine plagues that wreaked havoc in Egypt have not moved Pharaoh, but it seems they have moved the Israelites. Having witnessed from afar the power commanded by Moses and Aaron, and having marveled at their own immunity from the devastation wrought by that power, the Children of Israel have at last overcome their skepticism. They bow their heads in humble obeisance—the text does not say to whom; could it have been Moses?—and they then proceed to do as “the Lord had commanded Moses and Aaron.” In so doing, they tacitly vote for and begin to earn their deliverance. They are ready to be redeemed.

But wait: surely a word of caution is warranted. Once before the people believed Moses and Aaron when they promised the Lord’s deliverance. Then, too, “they bowed their heads and prostrated themselves” (4:31). But their faith was fickle, and easily destroyed when Pharaoh increased their burdens. Might it be fickle again? And in noting their obedience now, are we claiming too much for their freedom of choice? Their circumstances have long been desperate. What have they now to lose by hearkening? Besides, they have been threatened with destruction should they disobey and fail to mark their doors, and the evidence of the first nine plagues has made those threats quite credible. In short, what looks to us like a free choice may have been experienced as compulsion.

Still, these cautions do not finally persuade—at least, not if we try to imagine ourselves in the existential situation of the Children of Israel. Granted, they were between a rock and a hard place: marking their doors is risky, should the very visible Egyptians take notice; but so is leaving them unmarked, should the invisible Lord in fact pass through. Yet the Children of Israel did not waver. They unhesitatingly took the risk and place their trust in the promise of the Lord as communicated to them by Moses.

What followed for them must have been a terribly anxious night, from dusk to deliverance; they could have had no certitude that the Lord would strike selectively as promised, or that the Egyptians would not avenge their putting sheep’s blood on their doorposts. But they were not paralyzed, they were not cowed, and they were not compelled. They chose, and chose freely.

V. The Plague of the Firstborn

Compulsion is precisely what the Lord has in store for Pharaoh. The day of reckoning has arrived:

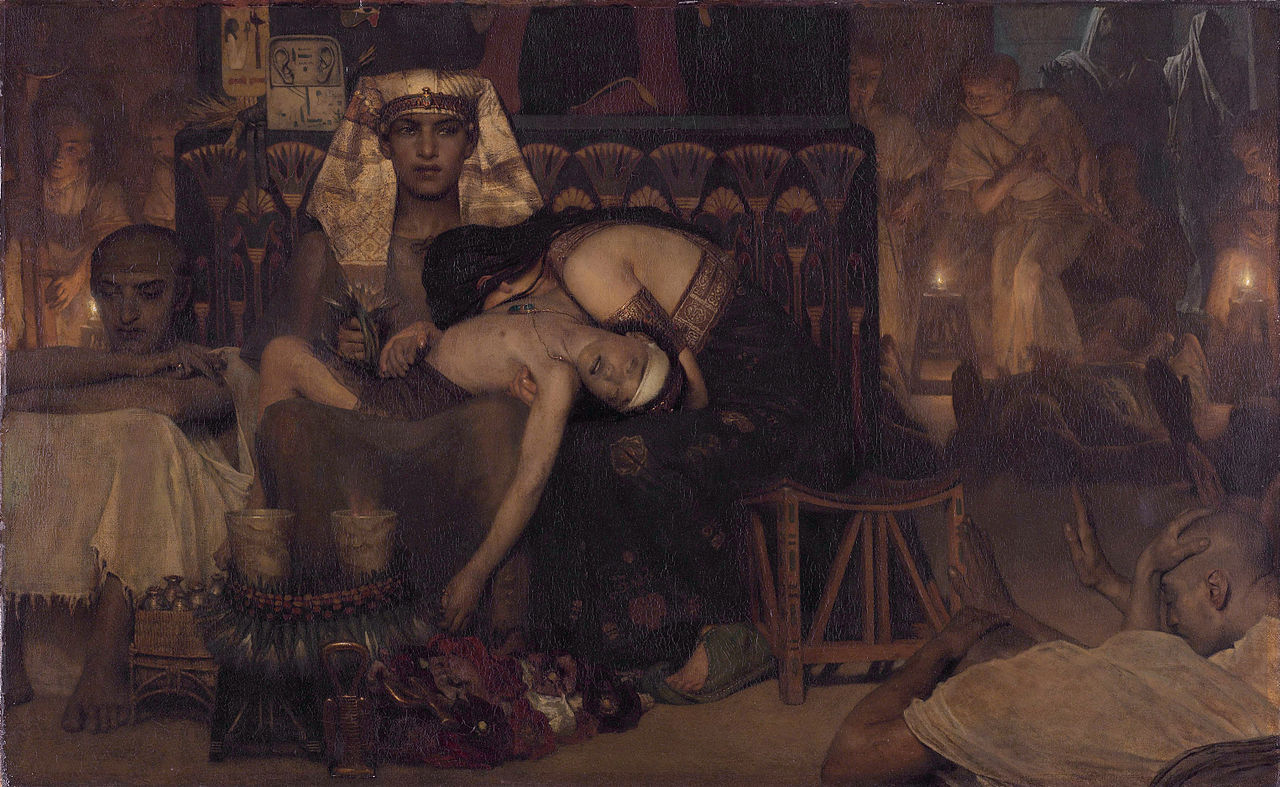

And it came to pass at midnight, that the Lord smote all the firstborn in the land of Egypt, from the firstborn of Pharaoh that sat on his throne unto the firstborn of the captive that was in the dungeon; and all the firstborn of cattle. And Pharaoh rose up in the night, he, and all his servants, and all the Egyptians; and there was a great cry in Egypt; for there was not a house where there was not one dead. And he called for Moses and Aaron by night and said: “Rise up, get you forth from among my people, both you and the Children of Israel; and go, serve the Lord, as you have said. Take both your flocks and your herds, as you have said, and be gone; and [or ‘but’] bless me also.” (12:29-32).

In elevated style, but with economy of expression, two verses suffice for the climactic tenth plague. Without warning, in the middle of the night, catastrophe strikes every Egyptian household, exactly as Moses has told Pharaoh. Also as predicted, there was “a great cry in Egypt” as the ubiquity of death and grief leveled all distinctions, from palace to pit. Overthrown symbolically are also the “gods” of the Egyptians, who—like the “divine” Pharaoh—are impotent to stave off the slaughter imposed by a greater-than-natural power that can strike with discriminating accuracy.

Pharaoh, whom we last heard banishing Moses with the threat “never see my face again; for in the day you see my face you shall die” (10:28), is compelled to summon Moses and Aaron in the middle of the night and, in abject capitulation, grant all of their demands. He begins in the imperative mode: “Rise up, get you forth.” But the content is entirely a humiliating concession to all of Moses’s prior demands: separate yourselves from among my people; not only you but your children; go serve Y-H-V-H “as you have said”; not only your children but take also your flocks and herds “as you have said.”

The end of Pharaoh’s speech—his last ever to Moses and almost his last altogether—is full of pathos: it begins with a face-saving attempt to assert authority—“And be gone!”—but then in a submissive about-face, recognizing that the Israelites have been blessed and that only the Lord of Israel can save him, Pharaoh pleads for a blessing also for himself.

As did Pharaoh with Moses and Aaron, so do the terrified Egyptians with the Israelites: they press them hard to leave:

And the Egyptians were strong upon the people, to send them out of the land in haste; for they said: “We are all dead men.” And the people took their dough before it was leavened, their kneading troughs being bound up in their clothes upon their shoulders. And the Children of Israel did according to the word of Moses; and they asked of the Egyptians jewels of silver, and jewels of gold, and raiment. And the Lord gave the people favor in the sight of the Egyptians, so that they let them have what they asked. And they despoiled the Egyptians. (12:33-36)

Encouraged by their Egyptian neighbors, the Israelites do not need much convincing to leave. Hastily taking their unrisen dough, but keeping it under their clothes in the hope that their bodily warmth might cause it to rise, they make their exit from the land. But as they are leaving, they remember Moses’s instructions—delivered much earlier at their first meeting with him and Aaron (4:29-30) when they received the plan that God had presented to Moses (3:21-22)—to ask their neighbors for gifts of jewelry and clothing. Exactly as the Lord had then predicted, the Egyptians now oblige, because “the Lord gave the people favor in the sight of the Egyptians.”

What does this mean? Why, and in what spirit, do the Israelites ask for wealth? Why, and in what spirit, do the Egyptians oblige?

The alternative to asking is taking. The instruction to ask, whatever else it may be, is a means to prevent looting and pillage. Just because we are reading the Torah, with its high-minded teachings, we shouldn’t imagine that this large mass of aroused, soon-to-be former slaves would, on their own, act differently from any other mob overthrowing their oppressors. They will want revenge and they will want payback for their labor and suffering, so they will take what they think is coming to them and more. Thanks to divine instruction, that does not happen here.

And what might they be asking for? Most likely, they are seeking compensation for their years of service. God had said, in his original prophecy and instruction, “When you go, you shall not go empty” (3:21), a phrase that will be repeated years later when Moses sets down the proper treatment in Israel of the manumitted Israelite slave:

And when you let him go free from you, you shall not let him go empty; you shall furnish him liberally out of your flock, and out of your threshing-floor, and out of your winepress; of that wherewith the Lord your God has blessed you, you shall give unto him. And you shall remember that you were a bondman in the land of Egypt, and the Lord your God redeemed you; therefore I command you this thing today. (Deut. 15:13-15)

Since the Israelite master has profited from the slave’s service, the slave is entitled, when gaining his freedom, to some share of the accumulated profit. And the reason given to the master for his duty to be liberal is none other than “his own” bondage in Egypt, from which the Lord his God redeemed him—also not empty-handed.

The Egyptians comply with the request because, we are told, “the Lord gave the people favor in the eyes of the Egyptians.” A rosy, not to say utopian, interpretation of this expression would suggest that comity, even brotherly feeling, had wondrously broken out between the Egyptians and their erstwhile enemies. Having themselves been terrorized and attacked, with slaughtered sons in every home, the Egyptians at last have fellow-feeling for the brutalized and long-suffering Israelites. As if repudiating Pharaoh and his policies, they are eager to make amends for their complicity in the Israelites’ oppression, and their gifts are intended as restitution and healing.

On such a hopeful reading, however, we can only be terribly disappointed to learn at the end that the Israelites “despoiled the [neighborly] Egyptians.”

I prefer a more hard-headed reading. The favor the Israelites win in the Egyptians’ eyes comes from the fact that the Lord is clearly on their side. The disaster that has just struck every Egyptian household is all the Egyptians need to understand where power really lies. The multitudes always love a winner, especially when they have more to lose by clinging to the losing side. Thanks (only) to the Lord’s display of matchless power, the Egyptians now look favorably upon His people. The gifts they give the Israelites are both tributes for victory and bribes to avoid further punishment. In the eyes of the Egyptians, the Israelites’ request was an offer they could not refuse. “And so they [the Israelites] despoiled the Egyptians,” getting freely some portion of the recompense their former service deserved.

There is a third, and perhaps better, interpretation of the Egyptians’ behavior. At the penultimate stage in the contest of the plagues, just before Moses warns Pharaoh about the tenth plague, we readers were told that “the man Moses was very great in the land of Egypt, in the sight of Pharaoh’s servants and in the sight of the people” (11:3). As Pharaoh’s credibility and reputation sank with each mounting plague, the Egyptians—everyone other than Pharaoh—came to see that Moses was for real, and so, therefore, might be the people and the divinity he claimed to represent. Having previously thought of the Israelites as lowly and powerless, the Egyptians had not respected them, but their attitude was changing. Now, with the final attack on the firstborn, every Egyptian household can see that the Israelites are aligned with a powerful deity and therefore worthy of respect. The Egyptian gifts, given on request, are signs not of affection but of grudging—and awe-filled—respect.

VI. The Departure

At long last, the Israelites leave Egypt. For such a momentous event, the text’s description is almost anticlimactic:

And the Children of Israel journeyed from Rameses to Sukkot, about six-hundred-thousand men on foot, beside children. And a mixed multitude went up also with them; and flocks, and herds, even very much cattle. And they baked unleavened cakes of the dough which they brought forth out of Egypt, for it was not leavened; because they were thrust out of Egypt, and could not tarry, neither had they prepared for themselves any victual. (12:37-39)

The account is brief, spare, and straightforward. The numbers departing are staggering. Some non-Israelites—“a mixed multitude”—have joined the Exodus. From the start, all were under-supplied with food; what they had was only unleavened flatbread. They were free but hungry. Before long, they will regret their choice.

Israel is out of Egypt. The story of their servitude is over. In concluding this phase of Israel’s experience, the text invites us to look back at the long history of exile:

Now the time that the Children of Israel dwelt in Egypt was four-hundred and thirty years. And it came to pass at the end of four-hundred and thirty years, even the selfsame day it came to pass, that all the battalions of the Lord went out from the land of Egypt. It was a night of watching [“observance” or “vigilance”] unto the Lord for bringing them out from the land of Egypt; this same night is a night of watching unto the Lord for all the Children of Israel throughout their generations. (12:40-42)

The prophesied 400 years of slavery (see Gen. 15:13) have ended. The 70 Children of Israel who came into Egypt as the sons of one man leave as the battalions of the Lord. Their night of watching unto the Lord for His deliverance becomes, in the final sentence, the basis for observing a night unto the Lord “for all the Children of Israel throughout their generations,” which is to say forever.

This last, forward-looking remark is the link to the first of the text’s two appendices to the Exodus, in which the Lord gives Moses and Aaron additional instructions about the ordinance of the Passover. Inspired perhaps by the presence of the “mixed multitude” among them, the seven succinct regulations are to make clear to the Israelites who is and who is not eligible to participate in the Passover sacrifice.

Participation in the sacrifice is to be restricted to Israelites, those within the Abrahamic covenant, including those who are willing to join the community (with their families) by being circumcised. Foreigners are not eligible to eat of the sacrifice; a manservant bought for money, when you have circumcised him, can participate, but settlers or hired hands who dwell among you but do not wish to join the community are to be excluded. The sacrifice is to be eaten in the house and not taken outside. The entire congregation of Israel—no exceptions—shall observe it. If a stranger sojourns with you and wants to keep the Passover, he may participate after all the males of his household are circumcised. After that, the sojourner shall be as a native of the land, but not until then: no uncircumcised person shall eat of it.

The regulations conclude with a general rule regarding outsiders: “One law (torah) shall be to him who is native and to the stranger that sojourns among you” (12:49). There is to be no discrimination against strangers who are willing to join the community.

These regulations, easily overlooked because they do seem anticlimactic, are in fact quite remarkable. As the Israelites set off on their journey to independent nationhood, something need be said about how porous the boundaries of membership should be between them and their neighbors. What is striking is how open to accepting strangers the Children of Israel are encouraged to be and, even more, how generous are the criteria for allowing outsiders to join their ranks.

The critical requirement for membership is not the blood tie of birth and ethnicity (or the ability to contribute to the gross national product) but commitment to the covenantal purposes to which the community is dedicated. One need not be a natural child of Israel to become a covenantal child in Israel. What is required is only male circumcision, the voluntary acceptance of the (nature-altering) sign of God’s covenant with Abraham and all of his future descendants: a covenant intended from the start to establish, perpetuate, and transmit a way of life devoted, in the first instance, to righteousness and justice (Gen. 18:19) and later also to holiness. Only people who willingly enter this same covenant can become full members of the nation that has been liberated from bondage in order to build a righteous and just political community—one where, among other things, strangers will be welcomed and justly treated.

These regulations having been communicated to the Israelites, the story of the deliverance comes to an end:

Thus did all the Children of Israel; as the Lord commanded Moses and Aaron, so did they. And it came to pass the selfsame day that the Lord did bring the Children of Israel out the land of Egypt by their hosts. (12:50–51)

VII. Consecration of the Firstborn

One more matter pertinent to the deliverance from Egypt is still to be addressed: the status of the firstborn. Just as the law prescribing future Passover observance immediately preceded the Exodus, so the law prescribing redemption of the firstborn immediately follows the Exodus. It appears at the start of the second appendix:

And the Lord spoke unto Moses saying, “Consecrate unto Me all the firstborn, whatever is first to open the womb among the Children of Israel, both of men and of beast—it is Mine.” (13:1-2)

We discussed at the start the import of this requirement: to counter parental pride in producing and possessing offspring, as well as contrary paternal (and cultural) impulses toward child sacrifice; to commemorate the sparing of the firstborn in Israel, purchased by the killing of the firstborn in Egypt; to overturn the widespread (including the Egyptian) presumption that what is naturally first should be humanly first (primogeniture); to teach that children are a gift, not of nature but of the Lord.

The Lord’s instruction, as far as we hear it, is contained in this single sentence. Looking ahead to the time of settlement in the Promised Land, He demands that He be inserted into the relationship between a father and his firstborn son (the b’khor: the one having priority according to birth or nature, the preferred one) and between a landowner and his firstborn animals. Against the natural belief that my son and my calf and lamb are mine, the Lord insists that they are His. Moreover, He asks that they be set aside or consecrated unto Him.

If we read only this sentence, we would think that He is demanding that they be sacrificed to Him. What other form of consecration could embrace both humans and animals? Only in the sequel, a fourteen-verse address by Moses, is this impression corrected. But the correction does not come right away. First, Moses sets forth the context in which the obligation is to be understood.

Before examining the content of Moses’s speech, which relates to memory and the education of children, I must comment on the mere fact of it. Most interpreters assume that Moses is simply conveying further instructions that the Lord gave him in private. I prefer to think that he is speaking on his own, perhaps intuiting what the Lord intends with his commandment about the firstborn but mainly seizing the opportunity for basic cultural instruction.

Here, and several times earlier, God has put into Moses’ mind the need to think about the future, about the children, and about how the children should be related to God. Moses grabs this occasion to expand on the subject, whether from newfound confidence in the people or from fear of their prospective waywardness. In the process, he creates the catechism for parents to use with their children. He turns their attention from liberation from to liberation for, to what they were liberated from Egypt to do: to their mission.

It is at this moment that Moses the statesman becomes Moses the teacher, or, as he is known in the tradition, Moshe rabbeynu: Moses our teacher. He uses his status as founding leader to devolve some of the responsibility for national perpetuation onto the people themselves, family by family, fathers to sons. He teaches parents the central importance of teaching itself, while also creating the national narrative that is to be taught.

He begins with the obligation to remember the Exodus and to celebrate Passover:

And Moses said unto the people: Remember this day, in which you [plural] came out from Egypt, out of the house of bondage; for by strength of hand the Lord brought you out from this place; there shall no leavened bread be eaten. This day you go forth in the month of Aviv. And it shall be when the Lord shall bring you [henceforth singular] into the land of the Canaanite, and the Hittite, and the Amorite, and the Hivite, and the Jebusite, which He swore unto your fathers to give you, a land flowing with milk and honey, that you shall keep this service in this month. Seven days you shall eat unleavened bread, and on the seventh day shall be a feast to the Lord. Unleavened bread shall be eaten throughout the seven days; and there shall no leavened bread be seen with you, neither shall there be leaven seen with you, in all your borders. And you shall tell your son on that day, saying: “It is because of that which the Lord did for me when I came forth out of Egypt.” (13:3-8)

The Children of Israel are told to remember this day, on which the Lord delivered them out of the house of bondage in Egypt, as a day for eating no leavened bread. Even (or, better, especially) when they come to the rich Promised Land, a land flowing with milk and honey—as prosperous as Egypt—they must keep this annual service to the Lord, a bulwark against any Egyptianizing temptation.

The essence of this service, repeated four times in two verses, is the eating of flatbread and the abstention from leaven. And what is the point? To be able to tell your son that you eat this flatbread and do this service because of your personal deliverance from slavery, a gift of the Lord. You are not only to remember but you are also to “remind” your children of your personal debt to the Lord.

In reading this account, imagining ourselves among Moses’s listeners, it may occur to us to ask: are we eating flatbread and telling our children because God took us out of Egypt, or did God take us out of Egypt so that we could eat flatbread and tell our children—so that we could serve Him by keeping the memory of His beneficence alive from generation to generation? Have we been liberated not to be free but to have a story to tell—to ourselves, our children, and indirectly to the world? Have we been liberated so that everyone, forevermore, shall know and remember the Lord?

The obligation of memory is the subject of Moses’s next instruction:

And it shall be for a sign unto you upon your hand, and for a memorial between your eyes, that the law [torah, teaching] of the Lord may be in your mouth; for with a strong hand has the Lord brought you out of Egypt. You shall therefore keep this ordinance in its season from year to year. (13:9-10)

The plain meaning of “sign upon your hand . . . memorial between your eyes” is unclear. We cannot be sure whether it is meant literally or metaphorically. Either way, however, the sign upon the hand recalls the Lord’s mighty hand; the memorial between the eyes recalls the deliverance from Egypt. But the main thing is the purpose of these reminders: that the (not-yet-given) law of the Lord may be in your mouth, to guide your life and teach your children, from year to year, indefinitely.

It is in the context of teaching the children the Lord’s torah that Moses finally gets around to the consecration of the firstborn. He introduces a distinction, not present in God’s original one-sentence directive, between what is to be done with the firstborn of beasts and with the firstborn of humans:

And it shall be when the Lord shall bring you into the land of the Canaanite, as He swore unto you and to your fathers, and shall give it you, that you shall cause to pass over [that is, to be sacrificed] unto the Lord all that first opens the womb; every firstling that is a male, which you have coming of a beast, shall be the Lord’s . . . but all the firstborn of man among your sons you shall redeem. And it shall be when your son asks you in time to come, saying, “What is this?,” that you shall say unto him: “By strength of hand the Lord brought us out from Egypt, from the house of bondage; and it came to pass, when Pharaoh was hard about sending us off, that the Lord slew all the firstborn in the land of Egypt, both the firstborn of man, and the firstborn of beast; therefore, I sacrifice to the Lord all that opens the womb, being males; but all the firstborn of my sons I redeem.” And it shall be for a sign upon your hand, and for frontlets between your eyes; for by strength of hand the Lord brought us forth out of Egypt. (13:11-16)

When the Israelites come to inhabit the Promised Land—lest they forget how they got it, what they owe, and to Whom—they will be obliged to sacrifice the firstlings of their flocks and herds, presumably as acts of thanksgiving, unto the Lord to Whom all life belongs. But in repudiation of child sacrifice, including the sort that Pharaoh’s recalcitrance yielded among the Egyptians, the Children of Israel will be obliged to redeem their firstborn sons in memory of the Lord’s redemption of His firstborn son, Israel, from the house of bondage.

The human firstborn, no less than the animal firstborn, each a representative of its distinctive kind, is a creature of the Lord. But the human child may be redeemed—ransomed, bought back—because there are higher ways for him to be consecrated to the Lord.

The law regarding redemption of the firstborn in Israel has a distinctly political target: the practice, especially in settled agricultural societies like Egypt, of primogeniture, in which the naturally first is automatically the heir of his father’s domain. The Bible has from the beginning silently inveighed against the father’s preference for his firstborn—instead favoring Abel over Cain, Isaac over Ishmael, Jacob over Esau, Ephraim over Manasseh, Moses over Aaron—and making it clear that the naturally first is not the humanly best, especially if the standard is not might but right, especially if human affairs are not yet “set” according to God’s plan.

By claiming the firstborn for Himself and by insisting that consecration and redemption are the result of a human decision (“you shall consecrate unto Me,” “you shall redeem”), God is warning Israel against the complacent view that things are permanently settled or that mindless nature will properly order human affairs, and against the arrogant view that what is produced by nature and us suffices for human life.

But as the language of consecration implies, there is also more here than politics or the teaching of moderation. The point is decidedly spiritual and God-centered. Human children can be consecrated unto the Lord in ways other than sacrifice. Moses connects this teaching—about the redemption of the firstborn in Israel—to the subject of teaching itself.

Once again there is a child in need of instruction: he is puzzled by the laws of the firstborn and the different treatment of the animal and the human. “What is this?,” he asks—that is, what is the meaning of these precepts about the firstborn? The answer he gets explains the difference: we sacrifice the animal firstborn in gratitude for our deliverance from Egypt, and we redeem the human firstborn in memory of the price paid for our redemption. At the same time, we tacitly teach our children that, unlike other so-called gods, the Lord does not want child sacrifice. He wants only that our children be dedicated to His ways; He wants only that we remember gratefully His beneficence; He wants only that we continue to tell the story of how the world came to know Him.

Consecrating our children to the Lord is not only compatible with their remaining alive: it will be the basic condition of their flourishing.

VIII. What Liberation Is For

Israel is out of Egypt. Many of the Lord’s additional purposes have been accomplished. The Children of Israel, formerly passive, have started to act, and to act communally. Pharaoh has been compelled to send the people away, and he seems (for now) to acknowledge the superior power of the Lord, even asking Moses for a blessing. The Egyptians have also come around, looking with favor on the Israelites, formerly the objects of their contempt. Moses’s stature among both Israelites and Egyptians has risen; no longer worried about being a man with “uncircumcised lips” (6:12), he has gained confidence in his abilities to lead and to teach.

We are thus tempted to conclude that the contest with Egypt is over, and we can move on to the next steps in nation-building. But there is unfinished business. One more act must follow, and will follow in the next chapters of Exodus. Still, we have seen enough to be able to add a few new thoughts on the subject of freedom—of liberation from and liberation for.

As we noted at the start, the actual departure from Egypt, described in very few verses, is surrounded by instructions regarding ritual enactments of sacrifice, eating, and procreation. Some acts (marking the doors, preparing and eating the Paschal meal) were prerequisites for being redeemed from Egypt, while others (the annual Passover holiday, the consecration of the firstborn, the teaching of the children) are perpetual obligations into the future, intended to memorialize God’s deliverance of His people.

Before they could be liberated, the people had to choose to mark their doors, to deny and defy the gods of the Egyptians, and to vote for their deliverance, manifesting in all of these choices their obedience to the Lord and their trust in Him. After their liberation, the people were summoned to choose to keep the annual seven-day festival of eating flatbread and avoiding leaven; they were called upon to choose to consecrate their firstborn sons and animals to the Lord; they were invited to remember the Lord’s deliverance, to tell its story to their children, to educate their children in the meaning of the ritual observances by which Israel would forever define itself as a people—grateful to God for their existence as a people and devoted to keeping that relationship alive for themselves and future generations.

In brief, they were to use their freedom from Egyptian despotism and their own free choices to relive their national beginnings—the Exodus always first among them—and thus re-experience God’s presence in their lives.

Soon enough, the Israelites will be invited to enter into a covenant with the Lord in which they will be given many laws to guide their conduct toward each other and many additional rituals through which they are to relate to the Lord. The explicit goals of that covenant will be justice and holiness, the terms being defined by divine command, which terms they then freely choose to obey. They will be asked to choose to serve the Lord so that they may be lifted up to a higher plane of existence, making good on the promise inherent in their being made in the image of God.

That is what liberation from Egypt is ultimately for. The events and the teachings we have been reviewing here provide a beginning, and put them on the upward path.

This essay is excerpted from Founding God’s Nation: Reading Exodus by Leon R. Kass, to be published in January 2021 by Yale University Press. It appears here by permission of the author and Yale University Press. Copyright © 2021 by Leon R. Kass.

More about: Exodus, Hebrew Bible, Passover, Religion & Holidays