Before Leon Kass in the “People-Forming Passover,” there was Gotthold Ephraim Lessing (1729-1781).

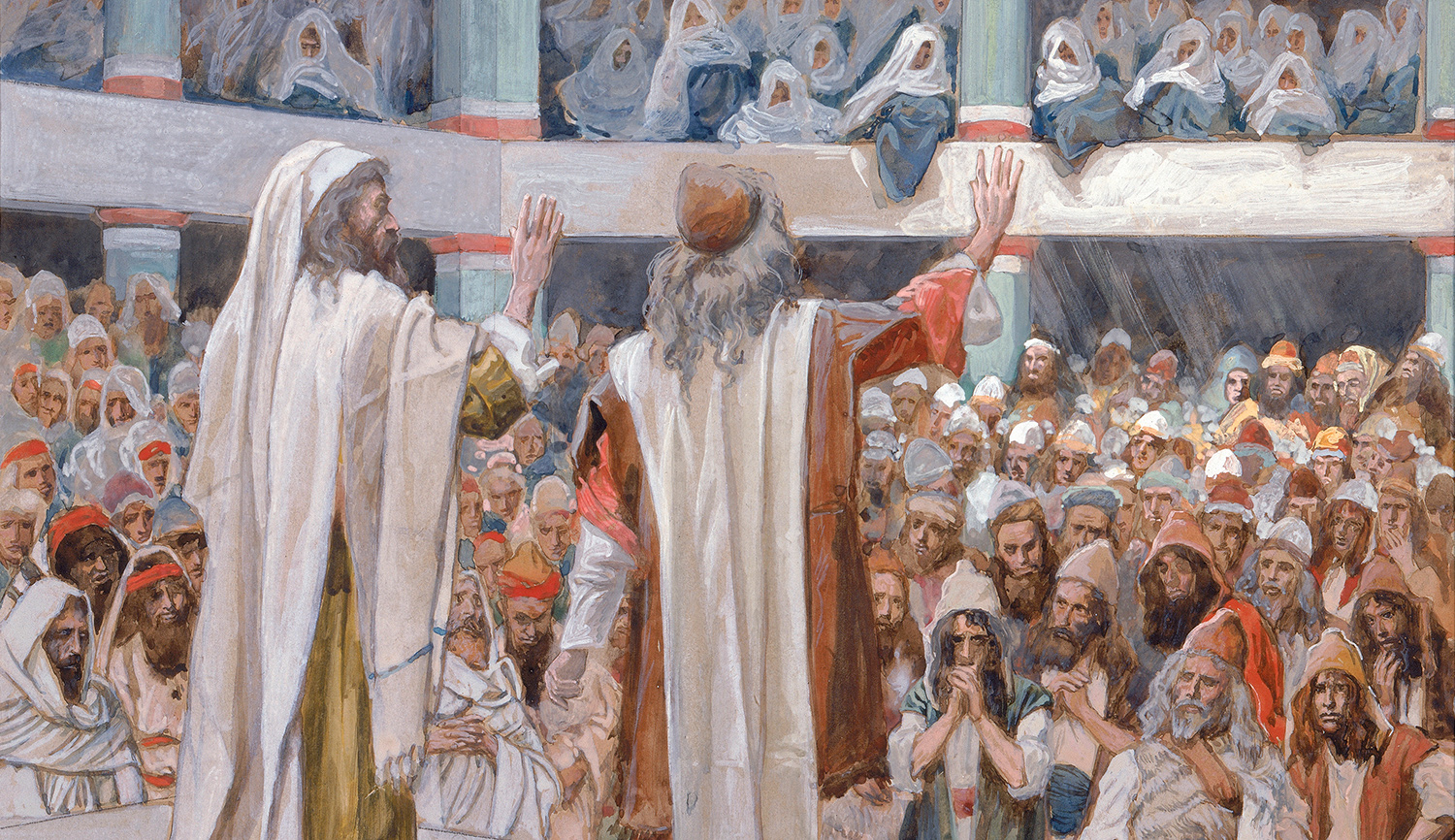

It was Lessing who proposed, in his 1780 The Education of the Human Race, that the best way to conceive of the God of the Bible was not so much as a Creator, World-Ruler, or Lawgiver than as an Educator. “That which education is to the individual, Revelation is to the Race,” he wrote in observing that the transition from the book of Genesis, in which God cultivates each of the patriarchs one by one, to the book of Exodus, in which he makes a covenant with an entire nation, reflects a “new impulse” in the biblical narrative. For when God “neither could, nor would, reveal Himself any more to each individual man, He chose an individual People for His special education.” Nor was the education of the Israelites an end in itself. Rather, in selecting them to be his pupils, God was “bringing up in them the future Teachers of the human race.”

Lessing’s formulation was an Enlightenment restatement of the traditional Christian view that, up to the advent of Christianity, the Jews were a crucial part of God’s plan for the world. In taking from Christianity its positive assessment of their role in human history rather than its condemnation of them for their subsequent behavior, which shaped the attitude of many other Enlightenment thinkers, he deserves praise.

And yet Lessing was giving God less credit than He deserved. What we read about in the opening chapters of the book of Exodus is not merely God’s choice of a people to educate. It is, as Leon Kass demonstrates brilliantly, His pre–schooling of the people He has chosen so that it will be able to learn all that He has to teach it when the time comes.

The Bible, however, is not just about the education of a people. It is also about the education of God. Indeed, it is precisely when it comes to God’s education that the Bible is at its most tragic.

This education already begins in the first chapters of Genesis, which start with God’s pleasure in creating a world “that was very good” and end with His nearly destroying it in His regret that He ever made it. From this, He comes to a conclusion. It is not enough to make a world, put a human race in charge of it, and leave it to its own devices. He has to take responsibility for what He has made by guiding this race step by step. This He does, as Lessing states, by starting with individuals—Abraham, Isaac, Jacob, Joseph—and proceeding to a people descended from them who will be His pilot project and the bearers of His teachings to all mankind.

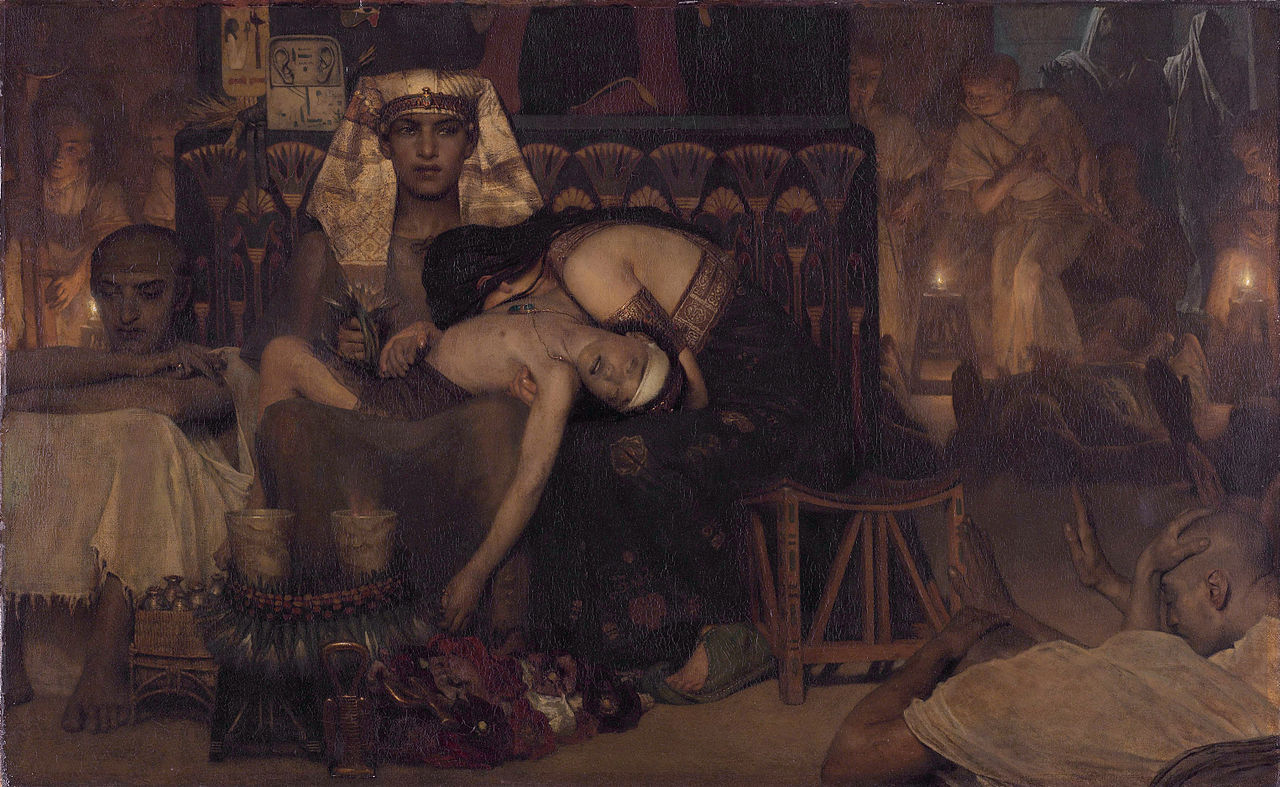

And so God brings the progeny of the patriarchs to Egypt and waits for them to multiply there until He thinks they are ready for their mission. The curtain rises on the next act, set in the opening chapters of the book of Exodus. Powerfully, it builds scene by scene. Chapter 12 of Exodus, analyzed in detail by Kass, continues on through chapters 13-15, which relate the Israelites’ departure from Egypt, their exhilarating escape at the Red Sea, and the destruction there of their enemies. It is a triumphant moment in which all indeed seems very good.

But the tragic is never far away. It will be first hinted at in Chapter 16, when the Israelites, their liberation from Egypt accomplished, begin to complain. Life in the desert is hard, they haven’t been warned of its deprivations. “Why have you brought us up from Egypt to bring death on us and our children?” they ask Moses, who calls out to God: “What shall I do with this people? Yet a little more and they will stone me.”

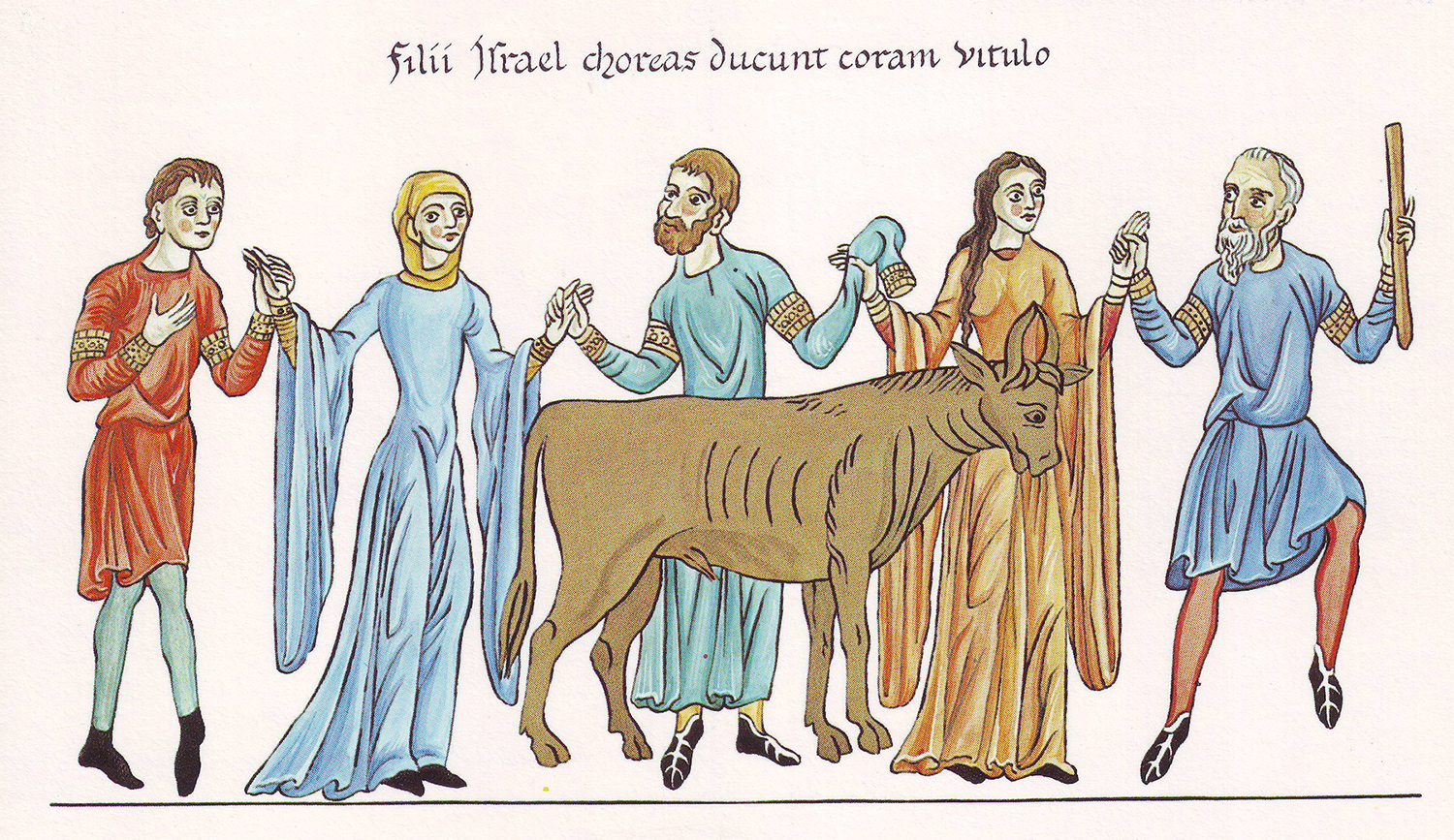

Complaint follows complaint, and it’s a very human tale: we exult in our deliverances for a brief moment and soon fall back into our everyday discontents. And the discontents of the first weeks in Sinai are but a minor prelude. The real fall occurs later, after the apogee of the giving of the Law, with the catastrophe of the Golden Calf. From Sinai’s heights, God’s pupils, having learned absolutely nothing from the extraordinary experience He has just put them through, plunge straight to the depths of depravity, worshiping an animal statue with bacchanalian rites. It is as if they have never left Egypt at all, let alone heard the voice declare from the mountain, “You shall have no other gods beside Me.”

What kind of people has God chosen? “Now therefore let me alone that I may destroy them,” He says to Moses in an echo of His determination in Genesis to drown all life when it disappoints Him.

The tragedy here is not Israel’s. It is God the educator’s. As happens time and again in the Bible, He is made to realize that the human race He seeks to educate, even that part of it that He has chosen to be its teachers, is so hopelessly uneducable that all of His most artfully conceived lesson plans come to naught. We never learn. We never will.

But neither does God. He is the eternal optimist. Failure after failure, He keeps on trying. The Golden Calf will be followed by the Tabernacle. The punishment of 40 years of wandering in the desert will end with the conquest of Canaan. The anarchy of the period of the Judges will lead to the First Temple, whose destruction will lead to the Second Temple, whose destruction will lead . . . and on and on. “Man plans and God laughs,” says the Yiddish proverb, but in the Bible, read to its tragic depths, the last, cruelest laugh is always on God.

And now, today, even His plans for our Passover, made so meticulously, their rationale spelled out so assiduously by Leon Kass, have been spoiled by a pandemic of human making. This wasn’t the seder He had in mind for us.

Neither I nor Leon Kass is young. We were both born in the same year, which saw the outbreak of World War II: a war on whose monstrous wreckage a new world was supposed to be built. It’s only too easy when one is old to confuse one’s own history of bright beginnings and gradual dimmings with the world’s, and I suspect that this is something that I am guilty of more than Leon Kass is. Still, when I think of those last days in Egypt—of the promise and excitement of setting out, the jubilation of being across the sea, and the first thrilling strides into a wilderness where the peaks of Sinai are waiting—I think above all of the sorrow that must be God’s.

More about: Exodus, Hebrew Bible, Religion & Holidays