Hillel Halkin

Hillel Halkin’s books include Yehuda Halevi, Across the Sabbath River, Melisande: What are Dreams? (a novel), Jabotinsky: A Life (2014), and, most recently, After One-Hundred-and-Twenty (Princeton).

The Value of Greek Wisdom in the Land of Israel

The liberal arts are on the retreat, perhaps even in danger of extinction, all over the world. What’s their future in the Jewish state?

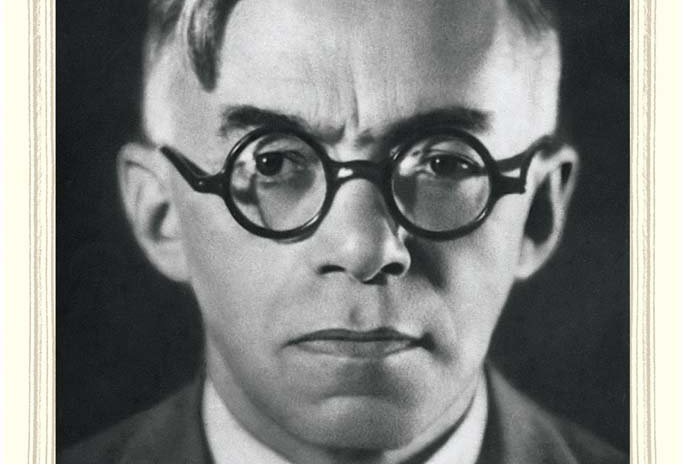

Did Jabotinsky Really Mean it or Was He Pandering?

Although the Zionist leader tried to avoid statements that didn’t reflect his true beliefs, he wasn’t above doing so altogether. His late-in-life friendliness to religion might be one such case.

Loss, Discovery, and a Lost Discovery in "Reading Ruth"

Parent-child collaborations are rare enough in literary history. Grandparent-grandchild collaborations are unheard of, until the publication this spring of a new study of the book of Ruth.

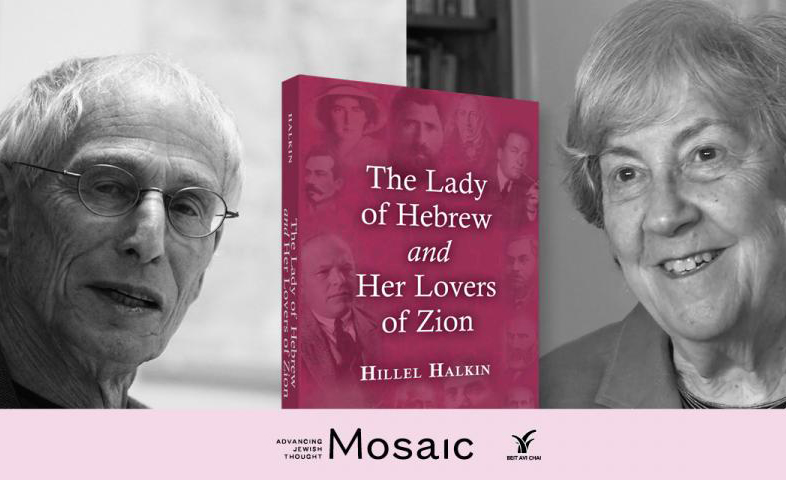

Podcast: Hillel Halkin and Ruth Wisse on His Life in Hebrew

The two giants of Jewish literature come together for a wide-ranging discussion centered around his new book on the seminal Hebrew writers of modernity.

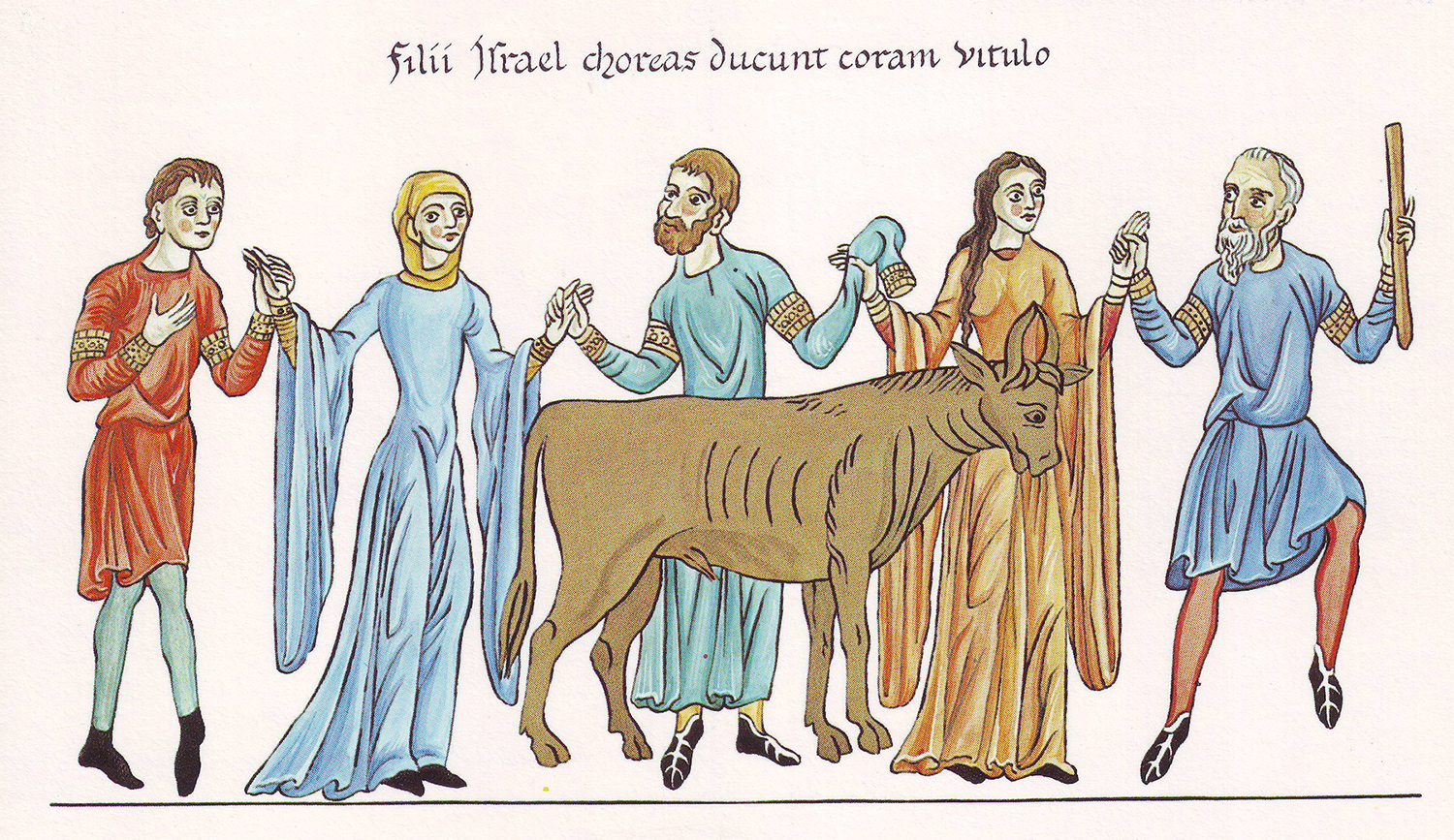

In the Hebrew Bible, Humans Never Learn. But Neither Does God.

Read to its tragic depths, the Bible suggests that the last, cruelest laugh is always on God.

A Tribute to Mosaic’s Founding Editor

Some of Mosaic’s regular writers reflect on Neal Kozodoy and his accomplishments.

Jews Wanting to Draw Others Closer to Judaism Should Ask Themselves Why

It’s all very well to be excited by the prospect of millions of new Jews. It’s something else to grasp that each already has a life that stands to be changed forever.

Bellow Between Hebraism and Hellenism

Bellow’s whole career as a writer was devoted to this dichotomy, sometimes veering toward one pole, sometimes toward the other, but never losing sight of both.

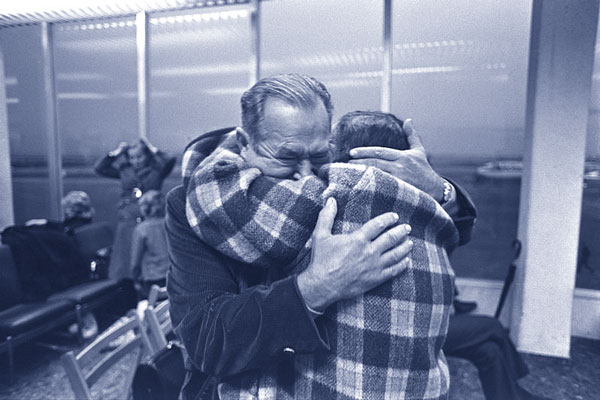

The Mind-Boggling Story of Shlomo and Yemimah Gangte

How a young man from a village in northeast India, convinced of his hidden Jewish roots, moved his family to Israel, became an Orthodox rabbi, and turned into a national hero.

The Necessary Bad Faith in Reading the Bible as Literature

For those who can’t say “I will obey,” but won’t say “I refuse to obey,” what other choice is there?

How to Judge Robert Alter's Landmark Translation of the Hebrew Bible

Finished after decades of labor, this one-man English translation is a stupendous achievement. How does it hold up against the masterpieces (and follies) that have come before?

The Agnon Wink

The great author was far from sentimental, and far from coy; he was the epitome of sly.

The Matchless Master of Modern Hebrew Literature

In his fiction, and especially in the novel Only Yesterday, S.Y. Agnon casts an ironic, unfooled eye on the inner lives of his fellow Jews and their lopsided bargains with modernity.

Jewish Historians Could Stand to Borrow a Trick from the Greeks

Curiosity—the most extraordinary of Greek traits—is a better prescription for writing Jewish history than is trying to breathe into it a “Jewish spirit.”

A Glorious Hebrew Poet—and Her Challenging Rhymes

It is almost as if English and Hebrew had gotten together and decided, “Yes, we don’t as a rule do well rhyme-wise, but for Raḥel we’ll make a special effort.”

The Life, Work, and Legacy of Israel's Most Beloved Poet

Raḥel will be read, sung, and recited long after many excellent Hebrew poets of her age, men and women alike, have been confined within classroom walls.

The Self-Actualizing Zionism of A.D. Gordon

How a philosopher who had never before engaged in hard physical work moved to Palestine, became an ascetic day laborer, and inspired a movement.

The Auto-Anti-Semitism of Yosef Hayyim Brenner

Why is the writing of this great modern Hebrew novelist so dark and anguished, and why does so much of it take such a ferociously negative view of Jews?

The Complex Greatness of the Jewish National Poet, Part Three

Ḥayyim Naḥman Bialik’s faith in a Zionist-led Hebrew renaissance never faltered; nor did his labors on its behalf. Yet he also became, so he felt, Zionism’s prisoner.

The Complex Greatness of the Jewish National Poet, Part Two

Ḥayyim Naḥman Bialik was called upon by his contemporaries to play the role of a prophet. By consenting, he believed he had betrayed both his talent and his true calling.

The Complex Greatness of the Jewish National Poet, Part One

In December 1903, Ḥayyim Naḥman Bialik burst to fame and notoriety in a storm of rage at Jewish passivity; by 1910, his poetic career had stalled.

The Vanishing of the Jewish Collective

Growing numbers of American Jews care about Israel only to the extent that Israel validates their own self-image. Israelis feel much the same way about them.

The Most Tragic Jewish Writer of Modern Times

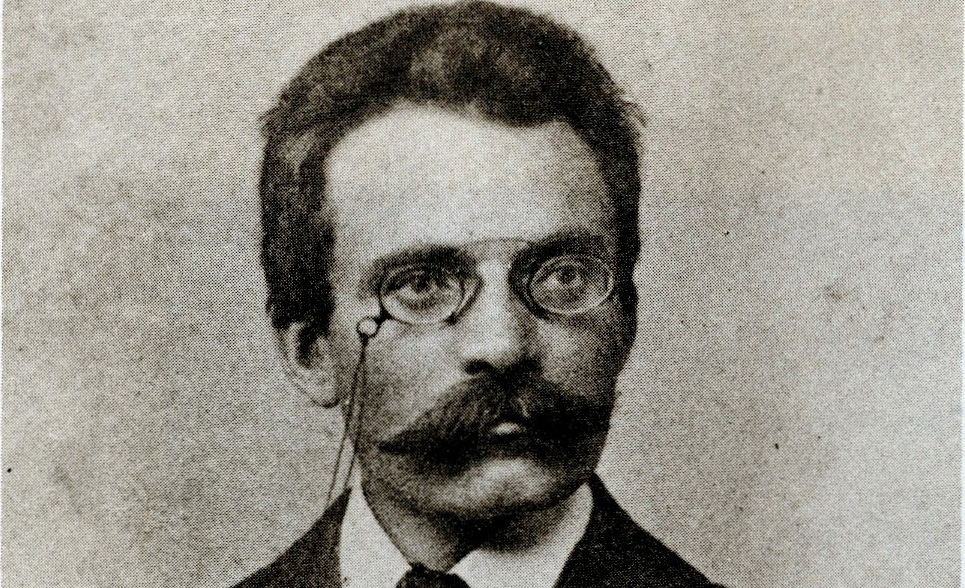

Why did the great Micha Yosef Berdichevsky, who called on Jews to take personal responsibility for Zionism, never settle in or even visit Palestine?

Why Ahad Ha'am Still Matters

Despite the failure of his cultural Zionism, the two main pillars of his thought remain central to Jewish life—and to arguments about Jewish life—today.

What Ahad Ha'am Saw and Herzl Missed—and Vice Versa

The unresolved rivalry between the great Zionist thinker and the great Zionist strategist still shapes the contending outlooks of many 21st-century Jews.

Like No Other People, Jews Remain Rooted in Their Past

None of the great Jewish arguments that raged in the 19th century—tradition versus modernity, secularism versus religion, nationalism versus universalism—is over with.

Where Is the Jews’ Homeland?

Elsewhere than Zion, said the greatest Hebrew poet of the 19th century—until he changed his mind, paving the way for others.

An Unparalleled Document of Jewish Mourning

The death of his brother in 1041 moved Shmuel Hanagid, one of Jewish history’s most extraordinary figures, to write nineteen piercing poems charting the rise and fall of his grief.

The Novelist of Jewish Unity

Did Jews recognizably still exist as a people in the late 19th century? Many questioned it. In his packed and vibrant fiction, the great Peretz Smolenskin proved them wrong.

Nothing Like It in 3,000 Years of Jewish Literature

The second Hebrew novelist was the first to imagine the pageantry and passion of life in ancient Israel—and thereby excited the dreams of emergent Zionists.

Sex, Magic, Bigotry, Corruption—and the First Hebrew Novel

In 1819, Joseph Perl published Hebrew literature’s first novel. A riotous satire of the ḥasidic movement, it remains largely and unjustly forgotten.

Who Was Jabotinsky?

Two-State-Minus

The two-state solution won’t work, the one-state solution won’t work. Where does that leave us?

What Has Zionism Wrought?

Zionism is at once the greatest repudiation of the Jewish past and the greatest affirmation of it.

Cause for Grief?

The Jewish people would suffer no great loss if all the Jews of Europe were to pack and leave tomorrow.