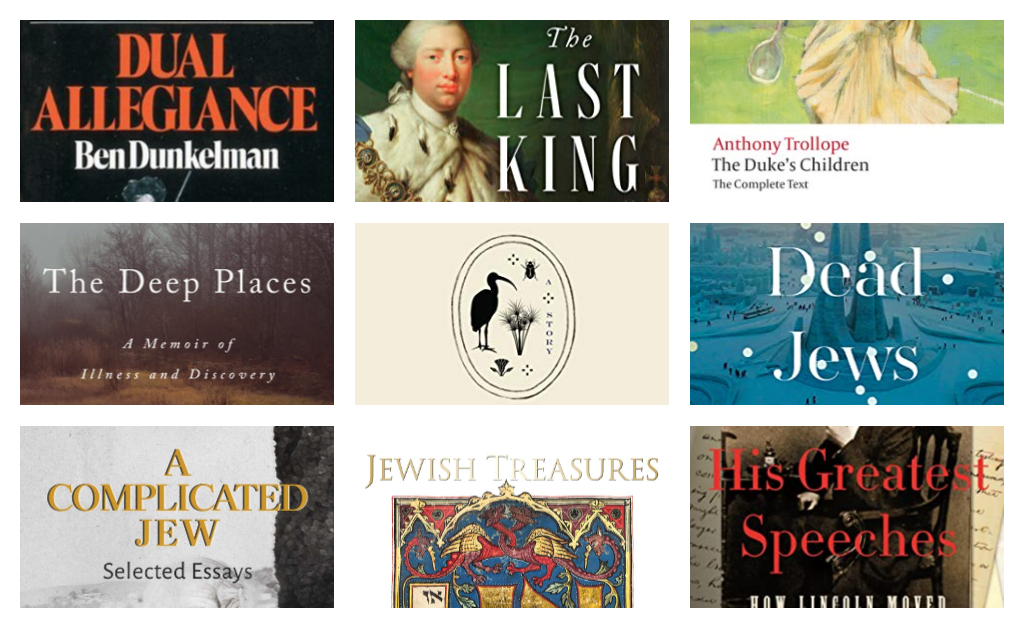

To mark the close of 2021, we asked several of our writers to name the best three books they’ve read this year, and briefly to explain their choices. We have encouraged them to pick two recent books, and one older one. The first five of their answers appear below in alphabetical order. The rest will appear tomorrow. (Unless otherwise noted, all books were published in 2021. Classic books are listed by their original publication dates.)

Elliott Abrams

Latest from the incomparable Andrew Roberts is The Last King of America: The Misunderstood Reign of George III (Viking, 784pp., $40). This is an absorbing and persuasive reevaluation of a king all Americans have learned, from the Declaration of Independence, to revile.

For Trollope lovers (like me), the last volume of the Palliser series, The Duke’s Children (Oxford, 736pp., $16.95) was published late in 2020 with the text restored to its original length after 140 years. Trollope was forced to cut 65,000 words by his publisher; now we have the text as he intended it, and it’s even better than the book we have known all our adult lives.

Jewish Treasures from the Oxford Libraries (Oxford, 2020, 304pp., $55) is a gorgeous book but not merely a coffee table adornment. (You can read Mosaic’s review here.) Organized by chapters telling the stories of their Jewish and more often Christian collectors, it discusses, and shows in many beautiful plates, the greatest Jewish items in the Bodleian Library and Oxford colleges’ libraries. The editors, Rebecca Abrams and Cesar Merchan-Hamann, combine Western history, Jewish history, art history, and Oxford history in this beautiful and fascinating book.

Richard Goldberg

Dara Horn, People Love Dead Jews: Reports from a Haunted Present (Norton, 272pp., $25.95). The mainstreaming of anti-Semitism in the United States under the banner of anti-Zionism continues to advance at an alarming pace. Confronting and dissecting the cognitive dissonance that leads some Americans to proclaim a deep love for Jews and Judaism while casting a vile disdain toward the political manifestation of Jewish power must be a high priority. We will look back at People Love Dead Jews as an integral step in broadening that conversation.

Jonathan Schanzer, Gaza Conflict 2021: Hamas, Israel and Eleven Days of War (Foundation for Defense of Democracies, 284pp., $29.95). As Hamas rockets rained down on Israel this spring, my phone felt like a switchboard with calls flooding in from around the country. Why was this happening? What was the trigger? Who is to blame? How did the detractors of Israel win the information war before the conflict even started? The political ramifications of the conflict continue to reverberate in Washington—and in Facebook groups and Instagram feeds across the country. Gaza Conflict 2021 is the year’s must-have book to help set the record straight about the war, its root causes, and the regional dynamics in play.

Hadassah Lieberman, Hadassah: An American Story (Brandeis, 160pp., $27.95). As we increasingly lose access to living testimonials of Holocaust survivors, the mission of Never Again lives on today through children and grandchildren who can share the stories of their youth—what it was like being raised by survivors in the shadow of humanity’s greatest horror. I’m grateful to Haddasah Lieberman for sharing her own story, and the story of her parents who survived the Shoah, and raised a family and achieved the American dream in its aftermath. Others should follow.

Neil Rogachevsky

Recently at a family gathering in Toronto, I suavely tried to educate some relatives about the role of two great Canadian Jews I’d come across in researching Israel’s War of Independence: Dov Yosef and Ben Dunkelman. As it happened, they were the ones to school me: “Oh, we already know all about Dunkelman. He was a great hero to Canadian Jews. Didn’t you know?” A hero he was and hero he should remain. And his memoirs Dual Allegiance (340pp., $19.99), published in 1976 and sadly no longer in print, ought to be in the canon of great Zionist works. The scion of a tailoring fortune in Toronto, Dunkelman fought in Normandy and Holland in 1944 with the Canadians and then played a pivotal role in the War of Independence, including laying the groundwork for the so-called Burma Road that allowed the supplying of Jerusalem when it was cut off by Arab forces and brilliantly commanding the Seventh Brigade of the Israeli Army in the battle for Galilee in 1948. A riveting read that could inspire young Diaspora Jews today about roles they could play in helping the Jewish state face future challenges.

Harder going but just as inspiring is Jewish Socratic Questions in an Age without Plato (Brill, 276pp., $150) by one of our premier scholars of medieval Jewish philosophy, Yehuda Halper. This unbelievably erudite work—the author moves with absolute authority through Greek, Arabic, and Hebrew texts—forms part of Halper’s revisionist enterprise to illustrate the true role of Greek philosophy in medieval Jewish thought, a subject that has more often than not been subject to caricature rather than research. And marvels abound within its pages.

If you’ll excuse a recommendation from the low domain of feature films in this forum dedicated to high-minded books, I enthusiastically recommend putting in the considerable legwork required to see Roman Polanski’s An Officer and a Spy (2019), which has not had a North American release. Based on Robert Harris’s novel, the film is a brilliant realistic portrayal of the Dreyfus affair that manages to do justice to the principal players involved in the drama as well as to the social and political context of the time. And, alas, the Dreyfus affair remains as relevant as ever.

Jonathan Silver

This year saw the publication of three extraordinary books that invite readers into the wisdom-seeking spirit of the Hebrew Bible. Nearly two decades after the publication of Leon Kass’s commentary on Genesis, The Beginning of Wisdom: Reading Genesis, he has now produced Founding God’s Nation: Reading Exodus (Yale, 752pp., $40), a superb, chapter-by-chapter study of Exodus. Mosaic excerpted parts of that book earlier this year. His intricate analysis of the construction of the Tabernacle is a model of careful reading and bold thinking. Also not to be missed are Kass’s Reading Ruth: Birth, Redemption, and the Way of Israel (Paul Dry Books, 125pp., $16.21), written together with his granddaughter Hannah Mandelbaum, in which he connects the Hebrew Bible’s most entrancing and lovely story with the anarchic political context of the book of Judges, and the Christian theologian Dru Johnson’s luminous Biblical Philosophy: A Hebraic Approach to the Old and New Testaments, a successor to Yoram Hazony’s 2012 Philosophy of Hebrew Scripture. Johnson presents two modes (“pixelated” and “networked”) and four styles (ritualist, transdemographic, mysterionist, and creationist) of thinking that together comprise a distinct Hebraic version of philosophy.

Almost everybody knows someone, or knows someone who knows someone else, who died because of the COVID-19 pandemic. Nearly 800,000 Americans have lost their lives because of the virus. The amount of human suffering has been immense. Reacting to this scale of death by turning away from religious introspection and denouncing God is understandable. But so is the impulse to seek out dimensions of religious faith that suffering brings to the surface. Ross Douthat’s The Deep Places: A Memoir of Illness and Discovery (Convergent, 224pp., $26) was not written about the coronavirus, but instead about his contraction of Lyme disease. The chapter “Where the Ladders Start” refers to William Butler Yeats’ poem “The Circus Animals’ Desertion,” and it portrays the religious possibilities of man reaching out in his broken desperation.

My favorite book about America last year was Wilfred McClay’s Land of Hope; this year, it’s Diana Schaub’s commentary on the rhetoric of Abraham Lincoln, His Greatest Speeches: How Lincoln Moved the Nation (St. Martin’s, 224pp., $27.99). On one front of our culture wars, we Americans now contest when our defining character was made manifest: was it when Jefferson articulated the ideals over which we declared independence in 1776, our political founding in 1787, or the fact of racial slavery, starting in 1619? Schaub’s ingenious insight is that three of Lincoln’s most significant speeches interpret these three very dates. His Lyceum Address teaches us to revere the Constitution and the founding of 1787. His Gettysburg Address teaches us that devotion to the principles 1776 requires a new birth of freedom. And finally, although we can never undo America’s original sin, the heinous crime of slavery that began in 1619, for the union to endure Americans must look upon one another with a democratic feeling of charity for all—that is, the political wisdom of Lincoln’s Second Inaugural.

Ruth Wisse

Cynthia Ozick’s short novel Antiquities (Knopf, 192pp., $21) is published in a deluxe format that makes it as lovely to hold as it is absorbing to read. (You can listen to Ozick discuss the book on the Mosaic podcast.) I adored it at once. The work takes brilliant revenge on those parts of America and of the English literary tradition that once had no use for the Jews. In a marvelously dissenting act of cultural appropriation (a woman speaking for a man, a Jew for a Gentile), Ozick adopts the voice of an aging trustee of one of those precious boarding schools once adorning the landscape of New England. In writing the history of this one, now in its last stages of decay, Lloyd Wilkinson Petrie finds that his dearest memories are of an exotic young Jew whom he befriended in his student days. But Ozick could never be satisfied with merely settling old scores. She invites our understanding of Petrie as he attempts to record the past and learns that its dearest parts cannot be preserved in antiquities.

The Mosaic review by Leon Kass of Hillel Halkin’s A Complicated Jew (Wicked Son, 304pp., $30) exceeds whatever I can say here—except in appreciation and praise. “Complicated” Halkin may be, but he is also the Jewish writer of my generation who most clearly transmits and interprets the complicated works of Hebrew and Yiddish literature, Jewish language, history, and thought. In that mode he has written book-length biographies of other complicated Jews, addressed the complexities of Jewish language, and tried to solve the intractable mysteries of the Ten Lost Tribes and the Zionist spies of NILI. Best of all are his essays, principally in Commentary and Mosaic, which I have been relishing since before the first (1974) that he has culled for this wonderful collection. There he describes having exchanged his 150 acres of land in Maine for less than one acre in Zichron Yaakov; the burial site he discovers in his garden confirms that “an acre isn’t so little when it comes with a coefficient of time.”

I cannot fail to include in this year’s offerings Justin Cammy’s translation of Abraham Sutzkever’s From the Vilna Ghetto to Nuremberg (McGill-Queen’s University, 488pp., $39.16). Sutzkever was a great modern Yiddish poet who wrote astonishing verse while in the ghetto, but after his escape, and as soon as he was able, he also provided this indictment of what took place under the Germans. Later he would draw on that material when chosen to testify on behalf of the Jewish people at the postwar Nuremberg trials. This edition includes an invaluable introduction and notes, a timeline, photographs, and additional material including Sutzkever’s impressions of the Yiddish writers he met in Moscow while composing this account.

Happily, rather than insisting on a fourth choice I can link to my recent encomium to Dara Horn’s People Love Dead Jews, but if I had I would also have needed to include Moshe Koppel’s Judaism Straight Up. What a year this has been!