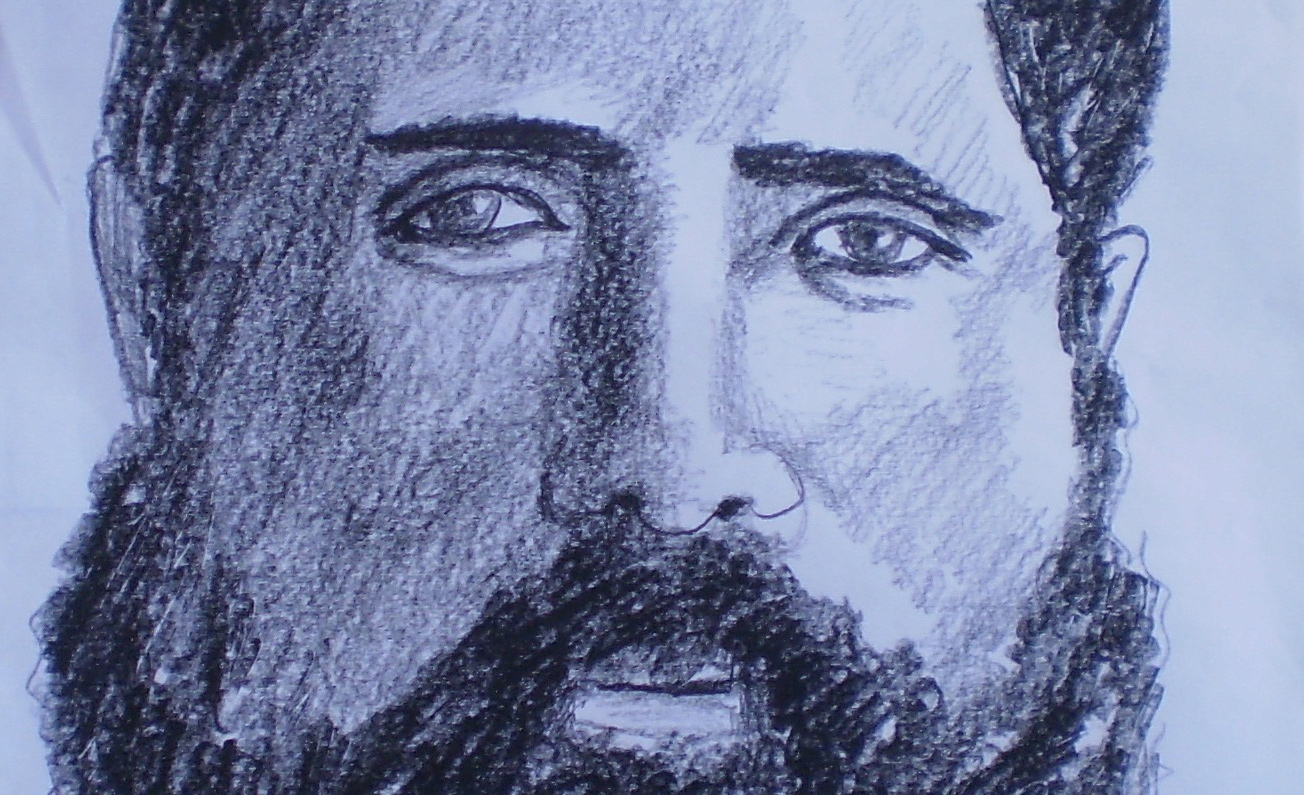

This, the eighth essay by Hillel Halkin in his series on seminal Hebrew writers of the 19th and early-20th centuries, is devoted to two figures: the novelist Yosef Ḥayyim Brenner (1881-1921) and the philosopher A.D. Gordon (1856-1922): “friends, mutual admirers, and public disputants.”

We present this essay in two consecutive parts: the first, today, focuses mainly on Brenner, and the second, tomorrow, mainly on Gordon and on the pair’s disagreements.

The preceding seven essays in Halkin’s series deal one by one with the novelists Joseph Perl, Avraham Mapu, and Peretz Smolenskin, the poets Yehudah Leib Gordon and Ḥayyim Naḥman Bialik, the essayist and Zionist thinker Ahad Ha’am, and the writer, journalist, and intellectual Micha Yosef Berdichevsky.

I.

How to translate the title of Yosef Ḥayyim Brenner’s Hebrew novel Mikan u’Mikan, the first major work of modern Hebrew fiction to be written in Palestine, where it is set at the end of the first decade of the 20th century? Until now this has been done, more or less literally, as “From Here and From There.” The Hebrew title alludes, among other things, to the novel’s seemingly casual structure, whose different parts may strike the reader as semi-independent vignettes, and “From Here and From There” conveys this impression.

But the novel’s tone is anything but casual. It is, like all of Brenner’s fiction, dark and anguished. Modeled on its author, the story’s narrator, a Hebrew-writing journalist who signs his columns of political and social commentary Oved Etsot or “Adviceless,” is a tormented soul who is living in Palestine despite the fact that he does not believe in the Zionist dream, does not believe in the Jewish future, and does not believe in the possibility of his own happiness. In all this he contrasts with another of the novel’s characters, the laborer-intellectual Aryeh Lapidot, based by Brenner on the figure of Aharon David or A.D. Gordon (1856-1922).

Brenner and Gordon knew each other well. They were friends, mutual admirers, and public disputants, as are Oved Etsot and Lapidot. Gordon, indeed, might have been describing Oved Etsot’s state of mind in Brenner’s novel when he wrote in his book Man and Nature:

The question is: is there any point or meaning in life when in it are death, sorrow, boundless suffering of every kind, lies, hatred, evil, imbecility, cruelty, pettiness, vileness, ugliness, filth, pollution, and tedium without end? Is there any point in living life with all of its contradictions and inconsistencies that tear the soul apart like a butchered goat? . . . As an “I” that has only myself in this world, whose vastness I contemplate as a detached, unnoticed, solitary, uncomprehending being buffeted from all sides like chaff on a threshing floor—what is it to me or I to it?

Let us then call Mikan u’Mikan “From All Sides.” This is no less true to the Hebrew and truer to the novel itself.

II.

From All Sides was the last of seven short novels that Brenner, who was born in 1881, published between 1903 and 1911—a highly creative period in which he also wrote two plays and numerous stories, sketches, articles, and essays. Because the novels and plays are heavily autobiographical, the outlines of his life can be traced through them, starting with his childhood and adolescence in a Ukrainian shtetl, where he grew up as the eldest child in a poor family. His first novel, In Winter, serialized in 1903-4 in the Hebrew journal Hashiloaḥ (of which the poet Ḥayyim Naḥman Bialik was then the literary editor), tells of this period; its central drama is a protracted struggle with a father who desperately wants his intellectually gifted son to pursue his religious studies, become a rabbi, and confer on his family the social prestige and financial security that it lacks. This struggle becomes increasingly exacerbated as the novel’s young narrator, Yirmiyah Feierman, loses his religious faith and willingness to go on lying about it to his parents, culminating in a bitter rupture with them.

Four passages mark the extreme swings of mood with which In Winter, which established Brenner’s reputation as an important Hebrew writer when he was in his early twenties, concludes. The first takes place on the eve of Yirmiyah’s final break with his parents. He has been having bad dreams, and in one of them

I was in a filthy sack. Sand was piled on my head and heavy rocks pinned my arms and feet. I struggled free from the sack only to be knocked back down by my father standing over me. . . . Then I was a fly sporting on Rakhil Moiseyevna’s cheeks. She grabbed my wings and snipped them off.

Rakhil Moiseyevna, a young woman Yirmiyah is too shy to declare his interest in, has none in him. His two dreams complement each other. The domineering father threatening to rebury Yirmiyah alive (it is obviously he who tied him in the sack in the first place) makes him feel as puny and helpless as a fly. The sexually rejecting woman (the Hebrew verb m’tsaḥek, “sporting,” has clear erotic overtones) symbolically castrates him. The two are allies in crushing him.

In a second passage, Yirmiyah’s sense of worthlessness and humiliating injury lead to the contemplation of suicide:

The good or ill of society—this world or another—liberty or servitude—pleasure and pain—free will and predestination—matter and spirit—the eternal and the transient—hunger and the life of luxury—knowledge and ignorance—faith and unbelief—what have I to do with any of these? If I were to listen to the voice of inner reason, I, Yirmiyah Feierman, would not go on living for another minute. And yet I’m alive and will be alive tomorrow. I’ll never free myself. I don’t have the will to free myself. I’m not free enough to free myself.

In my Bible is written: “Behold, before you are two paths. One is obligatory. The other is a voluntary exit. And thou shalt choose death!”

Yet how far I am from choosing it!

“Thou shalt choose life!” says the Bible that Yirmiyah was raised on—and in the next passage, he does. From the Russian city of N., where he is temporarily staying after parting with his parents for the last time, he writes to a friend:

Today the sun is out—not a wintry sun with its face of a pale, sickly woman but a hot, summery sun too strong for the naked eye. Light and warmth are everywhere—how I love life! Ah, brother, how I love it, how happy it makes me just to feel and to breathe! . . . I love all that is good, beautiful, pure, sublime, powerful, just. . . . Although I know that only more suffering awaits me in the future, I’m not afraid, not afraid at all.

Tomorrow I’m off.

When “tomorrow” arrives, however:

It was an overcast night.

At a small train station between N. and A. I was dragged from my hiding place beneath a bench in a third-class carriage and taken to the stationhouse.

I had no money or luggage. I sat there until told to go back to where I had come from.

“But it’s the middle of the night!”

“There’s a village near here.”

“How far?”

“No more than two miles.”

“Are there Jews there?”

“No, no Moshkes.”

“Then . . . how . . .”

“You’re being told to go!”

“You Jews,” growled the red-capped stationmaster. “Don’t think I don’t know all your tricks!”

I rose and walked off.

A tall policeman with nothing better to do escorted me.

I crossed the embankment with its bare piles. A lantern gave some light. Beyond it was a stack of wood on which I lay down.

A wet, sleety snow was falling.

It isn’t clear what Yirmiyah’s destination is and perhaps he, too, isn’t sure. He can’t go home, he can’t pay for a steamship ticket to America, and he has no entry point into Russian life, whose language he, a Yiddish speaker, is not fluent in. (He can’t even imagine asking for a night’s lodgings in a Russian village from anyone but a Jew.) Odessa, once headed-for by young Jews with literary ambitions like Peretz Smolenskin, the early Zionist writer Moshe Leib Lilienblum, and Bialik, has lost its allure. Yirmiyah’s only real option is to join other drifters like himself living on the fringes of Jewish society in the towns of the Pale of Settlement as odd-job holders, unmatriculated students, indigent Hebrew tutors, unemployed intellectuals, and would-be revolutionaries.

Such is the milieu of Brenner’s second novel, Around the Point, serialized in Hashiloaḥ again in 1904-5. Its protagonist, Yakov Abramson, an aspiring author with a background like Yirmiyah’s, has acquired the knowledge of Russian that Yirmiyah lacked. And yet he insists on writing in Hebrew even though few of his friends can read it or understand his commitment to it. Despite having given up the Jewish observance and study of his younger years, he remains viscerally attached to their language; it is too much a part of him to forgo. Told that he is writing an essay in it on the unrecognized contribution of Ḥasidism to 19th-century Hebrew literature, his friend Yeva Isakovna—née Chava—Blumin, a young revolutionary he is secretly in love with, predicts he will switch to Russian one day. When he answers, “Never,” she asks:

“But why not? You can’t deny you’d have more readers.”

“More? So what? “

“What do you mean?”

“Just what I said. What do I care how many there are if I have nothing to say to them?”

“It’s not true that you have nothing. You don’t want to have anything.”

“It’s all the same,” Abramson said morosely. “I don’t want to want. Look, Yeva Isakovna: let’s say that I could write—only that isn’t so—but let’s say I could write something of value in Russian and get it published in some monthly—there’s happily no shortage of Jewish journalists in the Russian monthlies—or even that my article on Hebrew literature were written in Russian for a Russian Jewish magazine. You’re right that I have no readers now at all. I admit it: none. Not that I would have any then, either—everyone knows that no one reads the Russian Jewish magazines—but at least in theory I might have. You, Yeva Isakovna, would certainly look for such an article and find it. But that’s just it! That’s just it! I won’t pretend it wouldn’t matter to me. It would. It certainly would. But the whole question has no relevance.” Abramson suddenly grew angry. “I’m a Jew and I write in Hebrew for Hebrews!”

Yeva Isakovna doesn’t suggest that Abramson write in Yiddish, the spoken language of the great majority of Eastern Europe’s Jews, as she would have done had she belonged to the Bund, the clandestine Jewish socialist movement founded in 1897, rather than to an all-Russian revolutionary organization. Although she presumably understands some Yiddish learned from parents or grandparents, she doesn’t read it or follow its literature, which came into its own in the 1890s with the mature work of Mendele Mokher Sforim and the fiction of Sholem Aleichem and I.L. Peretz. She has no use for Jewish separatism of any kind, let alone for the Zionism that Abramson believes in.

And Abramson is a Zionist mainly because of his feelings about Hebrew. Convinced that, despite the “bright spot of Ḥasidism,” as he calls it, the last several centuries of Jewish life in Eastern Europe have been “the most disastrous time in the history of Jewish exile,” he dreams in an Ahad Ha’amian vein of a great Hebrew cultural revival in Palestine in which “the original, once fertile Hebrew spirit will awake and be renewed.” Yet he disdains the pettiness of Zionist politics, and, gradually persuaded that Zionism cannot speak to the Jewish masses, he takes Yeva Isakovna’s advice, burns his Hebrew essay, and begins a new one in Russian that rejects all nationalism, Zionism included. In effect a call for Jewish assimilation made under the psychological pressure of his fear of losing Yesa Isakovna, this lands him in an emotional and psychological void. No longer recognizable to himself, he considers suicide like Yirmiyah Feierman, comes close to committing it, pulls back from the brink at the last moment, and suffers a breakdown at the novel’s end.

In an incipient form, Around the Point hinges on what was to be the central theme of From All Sides: the relationship between two different struggles to survive (or, more basically, to retain the instinct of survival): that of the Jewish people and that of the Jew identified with this people but fearful it is doomed. Abramson is an heir of the Haskalah: he shares its view of Jewry as a sick body that must either be made well or die. But he is also a product of the revolt against the Haskalah that started with Smolenskin and his age and intensified with the author Micha Yosef Berdichevsky and his. The Haskalah, such writers argued, diagnosed the symptoms of the illness without realizing that it was one of them. It urged the Jewish people to transform its life while undermining the religion that justified its will to live. All of the Haskalah’s proposed solutions to the Jewish problem—religious and educational reform, modernization, economic progress, and so forth—were those of an enlightened rationalism. But the will to live is irrational. It has to do, as Yirmiyah Feierman observes, not with reason but with a healthy vitality.

Which is, when Abramson looks at the Jewish world around him, what it is missing. This is why, religious unbeliever though he is, he regards Ḥasidism, for which the Haskalah had a special animus, as the one “bright spot” in modern Jewish history. For all of its backwardness from a maskilic point of view, Ḥasidism, as an early Maskil like Joseph Perl understood intuitively when he let the ḥasidic villains of The Revealer of Secrets run away with its story, was the most vital factor in 19th-century Jewish life. Its essential optimism; its sense of God’s everyday presence; the noisy hubbub of its prayer; the endlessly self-renewing rhythms of its song and dance; its limitless faith in its rebbes and the wonders they could perform: through all of these coursed a great, unreasoning life-force. An anti-ḥasidic joke told in maskilic circles expressed, like Perl’s novel, an unintended appreciation of this. A Maskil comes to a town one day and posts an announcement that he will give a lecture that evening on the subject of God. A large audience turns out to hear him. “Tonight,” he begins, “I will present you with seven proofs of God’s existence.” The Ḥasidim in the audience rise from their seats. “Atheist, get out!” they shout as one man and drive the Maskil from the town.

III.

From All Sides is set in 1909-10 in mixed Arab-Jewish Jaffa and the nearby Jewish village of Petaḥ Tikvah, then the largest and most prosperous of Palestine’s Zionist colonies, with flashbacks to other times and places. In an apologetic preface, its editor explains that its Hebrew manuscript consisting of six notebooks was found by him in the knapsack of “a suffering wanderer in our far-flung Jewish world” and that the decision to release it was made after an argument with its publisher. The latter, short of material, was eager to put it out; the editor was opposed. The manuscript, he tells the publisher, has no aesthetic value, “neither lyric pathos, nor intellectual breadth, nor an accomplished style, nor an architectural structure, nor the slightest manifestation of the world soul.” The publisher, though unaware that the notion of art as a manifestation of the “world soul” is a doctrine of the voguish Russian literary critic Vladimir Soloviev, concedes the truth of this while sticking to his guns. “But the content, . . . the Palestinian content!” he counters. “That’s what the public is looking for.” On the contrary, protests the editor: it is precisely what the public is not looking for. “There’s not a single description in it of the beauties of Mount Carmel or the Plain of Sharon, nothing about the fields walked in by the shepherd boy David, not a word about the bravery of our native youth or its mettle with a rifle or on horseback.” The Hebrew reader wants edifying descriptions of Palestine such as the manuscript does not provide. Yet ultimately, the editor informs the reader, he grudgingly agreed and prepared the six notebooks for publication.

Just how Oved Etsot’s knapsack—for the “suffering wanderer” is he—was found by the editor is unclear. Was it lost? Did Oved Etsot die somewhere in “the far-flung Jewish world” and leave it behind? Did he and the editor know each other? We aren’t told. What matters are two things, the importance of only one of which is grasped immediately—namely, that we are being asked to make allowances for the literary shortcomings of what we are about to read, since it was not intended to be read by others and should not be judged as though it were. What merits it possesses exist in spite of its style, not because of it.

The literary convention of the found manuscript, designed to inspire credence or forestall criticism, is ancient. (The oldest case of it is a Hebrew one—the “discovery,” according to the Bible, of the book of Deuteronomy by the scribes of King Hezekiah in the 7th century BCE.) For Brenner, it was but one of several fictional conceits employed in his novels to warn readers of the bumpy prose ahead. In Winter begins with Yirmiyah Feierman’s telling us: “I’ve prepared a fresh notebook in which I intend to sketch a few scenes from my life. . . . I’m writing this strictly for myself.” One Year, which relates the story of its protagonist Ḥanina Mintz’s (and Brenner’s) year as a conscript in the Russian army, is prefaced by the disclosure that it is a record of Mintz’s oral account to the narrator while walking the streets of a city one night. Breakdown and Bereavement, the last of Brenner’s novels, again starts with a private journal come across in an abandoned traveling bag. Although such fictions do not fool us, they bear a message from the author. “Don’t expect this book to be a work of art,” the message goes, “because my purpose is not to be artful. It is to be truthful—as truthful as I would have been had I transcribed something told me or found by me without changing it.”

Such a pretension to artlessness, of course, is a fiction, too. Brenner belonged to the first generation of East European Hebrew writers to be significantly influenced by Russian literature, and his approach to the novel reflected not only his own belief in honesty as a supreme value but the preference of much of 19th-century Russian literary criticism for a scrupulous, socially engaged realism. “Realism and aesthetics,” wrote this school’s most radical representative, Dimitri Pisarev, “are in a state of irreconcilable hostility” that can only end with “realism’s destruction of aesthetics” —and while no novelist can accept a formulation that would make of him a literary vandal slashing the canvas that he paints on, a serious novelist knows that it is possible to create the successful illusion of a slashed canvas. In one way or another, this is what all of Brenner’s novels seek to do.

Feigning an indifference to art while writing artfully calls for a technique of its own, and Brenner’s prose often has the same “deliberate clumsiness” that has been attributed to Dostoyevsky, the Russian author he felt closest to. Like Dostoyevksy, he took pains to write dialogue and interior monologue that mimicked the ungainliness of actual thought and speech. Abramson’s explanation to Yeva Isakovna in Around the Point of why he can’t write in Russian is a case in point. A more economical writer might simply have had him say, “It’s the same thing. I’m a Jew and I write in Hebrew for Hebrews.” All the meandering that takes him from his first sentence to his last one doesn’t advance the content of his remarks. It doesn’t even show the workings of his mind in any way that is unique to itself. What it shows is the workings of the mind, the roundabout way in which most of us stumble and grope while trying to make some point or arrive at some conclusion. In doing so, it creates an impression of reality as opposed to art, just as a painter’s trompe l’oeil tricks us into thinking that we are not looking at a painting.

Oved Etsot, like Abramson, often thinks aloud without organizing his thoughts beforehand. The first of his six notebooks is begun by him in a hospital in Jaffa, where he is recovering from a bout of illness. Wondering whether it is true, as is commonly believed, that a man’s entire life passes before him at the moment of his death, he writes:

O Psychology, where art thou?

But anyway, I’m not that ill. This isn’t my last day, and right now—or so it seems—that is, as of four o’clock this afternoon—my end hasn’t arrived. And yet my whole past is on view in my mind—my recent past, anyway—and it hasn’t been so bad, this past of mine—not so insignificant—as Psychology is my witness! . . . No, really. I accept it gladly, this past of mine; there’s nothing in it I regret. I’m sure that if I were nineteen again instead of twenty-nine and could decide to relive those ten years . . . yes, I’m sure, . . . but of what?

Brenner wrote such passages at a time when the spoken Hebrew revival was gathering momentum in Palestine with the introduction of Hebrew as the sole language of instruction in much of the country’s Jewish school system. From Smolenskin on, Hebrew literature had sought to make Hebrew seem a natural medium of communication even though its speakers were “really” talking in Yiddish or some other European language. In Brenner’s novels we have the attempt to make Hebrew seem a natural medium of consciousness even though most of its speakers are not yet thinking in it.

But Oved Etsot is quite capable of deploying a more literary prose style when he wants to. He does so in the next paragraph:

Ah, my past, my past! It’s always the same reckoning. In it are no royal honors, no annals of bravery; no revolutionary escapades or daring jail breaks; not a single mass rally at which I was cheered by thousands; not one brush with death or miraculous escape from it. The sad reality is that I have never even been clasped in the arms of a dancing beauty; never gone big-game hunting in Africa; never, for that matter, been as far as Transjordan.

Though more sardonic, this is close to the opening of In Winter:

My past! Anyone hearing me utter those words might think I had something frightful to disclose, some heart-rending tale. Not at all! My past is not of the slightest interest; there are no gripping events in it, no terrible tragedies; no murders or romantic dramas; not even a winning ticket in a lottery or an unexpected inheritance.

Yirmiyah Feierman is about nineteen when he writes these lines circa 1900—that is, he is the young man whom Oved Etsot, at the age of twenty-nine just like Brenner at the time of writing From All Sides, remembers himself having been ten years earlier. Yirmiyah, Yakov Abramson, Ḥanina Mintz, Oved Etsot: all are essentially the same person at different stages of the same life. Although the warning against confusing authors with their characters is always worth heeding, doing so is difficult in Brenner’s case. Thus, in his first notebook, Oved Etsot recalls the time spent by him in the city of “L.” in Austrian Galicia; Brenner, after deserting the Russian army and making his way to London, where he worked for three years as a Hebrew and Yiddish typesetter while publishing a Hebrew literary review, resided in Lvov, the Austrian Lemberg. From L., Oved Etsot departs for Palestine; so, from Lvov, did Brenner. After an abortive attempt at being a farm hand in Petaḥ Tikvah, Oved Etsot moves on to Jerusalem; Brenner followed the same route. Oved Etsot then returns to Petaḥ Tikvah, finds work writing for the Jaffa-based political and cultural biweekly Hamaḥreshah, “The Plow,” and serves on its editorial board; Brenner, now a contributing editor of Hapo’el Hatsa’ir, “The Young Worker,” the organ of a political party of the same name, was back in Petaḥ Tikvah after a few months in Jerusalem, too. It’s hard to tell the two men apart.

Oved Etsot looks back on the years before coming to Palestine as wasted ones:

What did I have in them? Wearisome days of writing and tutoring; dry bread to eat and plain water to drink; or else days in which I ate and did nothing but gnash my teeth; nights of loneliness . . . a young man’s rage at the cry of his repressed male nature; long hours of crushing, habitual despair.

The worthlessness of his own past, as Oved Etsot sees it, is analogous to that of the Jewish past. Both dismay him with their hyper-cerebralism, their remove from a healthy physicality, their lack of accomplishment in the real world. His life is Jewish history recapitulated. Describing a scene in Lvov in which he looks up from a book he is reading to regard an animated group of youngsters on their way to the theater, he writes:

With my bent back and the faded color of my distinctly unfashionable clothes (whose patches called to mind dead leaves blown under a park bench such as the backless one I was sitting on while reading Goethe’s Faust), I felt like a hoary old Jew, an anchoritic Essene from ancient times who had wandered by mistake into a pagan hippodrome where half-naked women pranced on noble horses.

“What really do I want?” he asks himself, rising from the bench. To which he gives the Zionist answer: “Land under my feet . . . redemption . . . a revolution from the ground up . . . a fundamentally new life!” Although he has no faith in the grand Hebrew revival that Yakov Abramson, too, has given up on, he regards Palestine as his and the Jewish people’s only hope of making a fresh start. He writes of his conversations with a friend, the symbolically named David Diasporin:

I explained to him that I, as a Zionist, didn’t dream of a rebirth of the spirit of the Hebrew nation but simply of getting away, away from the ghetto. “Renaissance,” risorgimento—those were charming words, but they had nothing to do with us; our world had no room for them; we weren’t Italy. Zionism meant for me only that it was time for that part of the Jewish people that still had some life in it to stop hanging on to others and blaming them for its faults. We Jews had to see ourselves, past and present, for what we were. The Hebrew spirit? It didn’t amount to a thing. Our great national heritage? Not worth a damn. For hundreds of years we lived among Polish and Russian brutes who spat on us, and all we did was wipe the spit from our faces and go on writing our imbecilic, text-twiddling books. That’s your Hebrew spirit! . . . I knew, I said, one thing: the only way to restore our honor and stop living like fleas was to seize our last chance and make a place for ourselves somewhere by dint of our own physical labor. Yes, our own labor! Every other people had lived, worked, and created for itself and for the generations that came after it while we were doing the devil only knows what. Not working was our primal sin; work, honest work, the only remedy for it.

Jews as fleas? Diasporin, who is staying with a well-off sister in Lvov after being turned down for admission by the local institute of technology because he is a Jew, teasingly calls Oved Etsot a “positively lyrical anti-Semite.” Having just referred to an attractive maid working in the sister’s home as “a pure Polish gem cast before Jewish bourgeois swinishness,” Oved Etsot, growing “serious, very serious,” replies: “Yes, I am one, perhaps even more of one than those who barred you from the institute. At any rate, I understand them.”

Brenner understood the anti-Semites, too. In his essay “A Self-Critique in Three Volumes,” written on the occasion of the publication of Mendele’s collected works in Hebrew, he wrote, addressing his readers:

Just between us, gentleman, I have a small question to ask—a small but difficult and even critical one that I’d be surprised to be told you’ve never asked of yourselves. Suppose that another people were to find itself in our place and that we ourselves were Germans, Russians, or whatever—wouldn’t we scorn it? Wouldn’t we hate it? Wouldn’t we instinctively accuse it of every fault and wrongdoing?

If there is a difference between Brenner and Oved Etsot, it is in their attitude toward Palestine. Brenner’s kept fluctuating. Hearing a rumor, while in London in 1906, that Hashiloaḥ was planning to move its offices to Jerusalem or Jaffa, he applied for work there as a typesetter and added, “To live in Palestine with a decent job has always, always been, for reasons I won’t go into here, my great desire.” Hashiloaḥ never made the move, but several months later Brenner wrote to the Hebrew writer Binyamin Radler, then living in Palestine, “One way or another, I’ve decided to come.” Nevertheless, he stressed in another letter to Radler, he would not be coming as a Zionist. “My journey to Palestine is almost certain,” he stated. “I want to get away from literature and everything ‘sacred.’ I want to work with my hands, eat, drink, and die in some field when my time comes. I have no higher ideal.”

A few weeks later, however, he wrote Radler a third time.

I’m not coming to Palestine after all. I hate the Chosen People and I hate the moribund, so-called “Land of Israel.” Feh! . . . I plan to bury myself in some hidden corner of London, work in a print shop, and never be heard from again.

To another Hebrew writer, his friend Asher Beilin, who was also thinking of a new life in Palestine, he wrote in September 1908 from Lvov: “What will you do there? I myself would go to New York if only I thought I could find literary work in Hebrew or Yiddish and earn a living.” And in January 1909, a mere three weeks before leaving for Palestine, he urged Beilin to join him in Lvov so that they might “open some business together. I’ll tell you what: if we see there’s nothing to be done here, we can always go to Palestine later.”

For Oved Etsot, Palestine is a “last chance.” For Brenner, it was a default choice. When he finally set out for it he did so, or at least so he told himself, for lack of a better alternative.

IV.

It would seem that Brenner made Oved Etsot the Zionist in L. that he, Brenner, refused to call himself only so that Oved Etsot could renounce his Zionism once in Palestine. His disillusion begins as soon as he steps off the boat. To Diasporin, now living with a brother in Chicago, he writes:

I disembarked in Haifa. . . . That first evening I went for a walk. What narrow, crooked, dirt-infested streets! And yet my belief that I had come home to my own land was great.

Two Jewish workers from a nearby colony rode toward me on donkeys, white cloths wrapped around their heads in the curious Arab style. The Orient! For a moment I thought: I’m really in a new world!

But there was no time to savor it, because a band of jeering Arab urchins burst from a squalid alley with a familiar tune: “Yahud!” I turned to the two men. “Why don’t I punch one of their noses, mates?” I said, feeling as brave and proud as a man should feel when the ground beneath him is his own. They quickly rid me of the notion. Didn’t I know we were in a city full of goyim, most of them Christians?

Now, too, then, . . . now, too, the world was full of goyim one had to take abuse from, . . . to take it even from filthy ragamuffins!

This is Oved Etsot’s introduction to the Arab problem, which he has not bothered to think about until now. In the weeks that follow, he is made aware of how Zionism is arousing Arab nationalism:

The cry of “Palestine, watch out for the Jews!” is already heard all over the Arab world and gaining in volume. Right now its venom is skin-deep, as is everything in Arab public life. It can easily work itself deeper, though. And that’s frightening.

Palestine has a Jewish problem, too. On his way to Petaḥ Tikvah, Oved Etsot stops at a Jewish farming village supported by the Baron de Rothschild. (Although unnamed by him, the village is clearly Zichron Ya’akov, twenty miles south of Haifa.) “The whole place,” Oved Etsot writes Diasporin,

was like a fat, ugly beggar seated at a rich man’s table and slurping his food from a bowl gripped by a gross, dirty, leprous hand.

The colony’s officials and administrators were like fattened hogs, too obese to take an unassisted step. . . . The half-naked, degenerate, groveling Arab farm hands outnumbered the Jews.

A second colony that Oved Etsot passes through does not have many Jewish workers, either:

I came to an inn there. Neglect and apathy were everywhere. The room hadn’t been swept, there was no hot water, and everyone in the innkeeper’s family tried getting someone else to take care of it.

Three Jewish workers sat around mournfully, one with a bad leg, one an old man, and one a thirteen-year-old boy. When they had gone to work in the fields that morning, two Arabs had set upon them and given them a beating.

The lamed man told me that the other two had run off and left him to fend for himself.

Oved Etsot reaches Petaḥ Tikvah:

The place was like a perfectly preserved Lithuanian shtetl; all that was missing was the Polish country squire. Most of the work was done by Arabs here, too, as if that were the normal order of things. There were a few Jewish farm hands, idealists like myself. (Yes, I was one of them for a while—the self-delusion, the self-abasement of it!). . . . We were living proof that the simple, healthy, natural life of physical labor isn’t for us. Fruit trees can’t be grown in a flowerpot. Finis! On the likes of us, life could only choke.

He tries life in Jerusalem. There, a long scene takes place in front of a public library, where a group of Jews, come to read the week’s newspapers, congregates one Saturday morning while waiting for the doors to open. All but one of them, a young, unnamed newcomer from Russia (Oved Etsot writes about himself here in the third person), belong to Jerusalem’s Orthodox community, which forms the bulk of the city’s Jewish population. Each a representative type, most are spongers of one kind or another. When the library finally admits them, the young Russian lingers outside with a yeshiva student who has only one good eye.

“Jerusalem!”—The young man uttered the word half-aloud, his sight dimming. It was one big religious artifacts shop, every item on display. No, it was a butcher shop in which holiness was sold by the pound. . . .

“Jerusalem!”—The young man swallowed his saliva. Palestine’s only city with a Jewish majority, and what a majority! . . . Carnal Jews without a drop of real blood with which to satisfy their carnality—with which to satisfy even one basic need. . . . Sickeningly crafty, calculating Jews who didn’t know the meaning of love for any place on the surface of the earth—lacking the slightest human skill or trade—as sunk in a dream-world as any savage and without a single ideal—living the life of trodden-on worms and as proud of it as a Ḥasid granted the honor of eating the leftovers from his rebbe’s plate . . .

“What . . . what will become of us in the end?” the young man asks the yeshiva student.

“Eh?” The student gawked without interest. His two eyes, the good one and the blind one, were like the holes punched in clay by Jewish housewives to stick their Sabbath candles in.

“We Jews . . . is there no cure for us? None at all?”

“None,” declared the other gloomily. “Farfaln!”

The Yiddish word for “it’s all over with” falls like a judge’s gavel.

A positively lyrical anti-Semite! In 1910, of course, there was no need to dislike Jews in order to see the deficiencies of the Zionist enterprise in Palestine. The country’s Jewish population was barely ten percent of its Arab one and growing slowly, if at all. The Rothschild colonies of the “First Aliyah,” the Zionist immigration that began in 1882, were still dependent on the cheap Arab labor and financial subsidies for which Ahad Ha’am had lambasted them nearly twenty years previously in his “The Truth from the Land of Israel.” The young “Second Aliyah” ḥalutsim (pioneers) who arrived in the first decade of the century, most with socialist ideals brought from Russia, had trouble finding work and suffered from unemployment, low pay, harsh living conditions, and malaria; morale among them was low, re-emigration high, and suicide not infrequent. The Orthodox inhabitants of Jerusalem, Palestine’s main urban Jewish center, lived partly or wholly on charity from abroad. All this painted a depressing picture.

But Oved Etsot could have seen other things, too, had he cared to. By 1910, there was a modern, secular Jewish community in Jerusalem alongside the Orthodox one. The first houses of Tel Aviv were being built on the sands north of Jaffa. The Rothschild colonies were closer to standing on their own feet; the actual Zichron Ya’akov was a lively village with a native-born generation that spoke Hebrew, worked in the fields, and was indeed skilled “on horseback and with a rifle.” Degania, the agricultural commune that was to become the first kibbutz, was founded in 1910 by Second Aliyah pioneers on the shores of the Sea of Galilee. There was a new spirit in the yishuv, a sense that a turning point had been reached. This was the Palestine that had impressed Bialik in 1909 and that the literary critic and historian Yosef Klausner had enthused about in 1912.

Klausner was mocked for his enthusiasm by Berdichevsky, and Oved Etsot is a mocker, too. Worse than one. “Gross, dirty, leprous hands,” “fattened hogs,” “carnal Jews without a drop of real blood,” “sickeningly crafty, calculating Jews”—who but a self-hating Jew would describe Jews this way?

The connection between Brenner’s negative feelings toward Jewishness and his negative feelings toward himself has been commented on extensively by Hebrew literary critics, whether to attack him as a shameless defamer of his people or to defend him as an uncompromising voice of integrity writing from a place of deep pain; in either case, he has been considered the most extreme expression of a revolt against Jewish tradition that runs through modern Hebrew literature. The Israeli critic Baruch Kurzweil, writing in the mid-1960s, sought to put the question in a wider perspective. While a critique of Judaism can be found in Hebrew literature from the beginnings of the Haskalah, he wrote, “all that seems revolutionary in the demand for a ‘transvaluation of values’ in Jewish life in the works of Mendele, Smolenskin, Lilienblum, the Hebrew writers Y.L. Gordon and Avraham Mapu, and even Berdichevsky is child’s play compared to its unbridled ferocity in the fiction of Brenner.” The “auto-anti-Semitism” in Brenner’s work has no real Hebrew parallel. It can be understood better, Kurzweil proposed, by placing it alongside a similar phenomenon in a number of European authors of the times, particularly the three German-writing Jews Franz Kafka, Otto Weininger, and Karl Kraus.

Although Brenner grew up in the religiously traditional and poverty-stricken world of Eastern Europe and Kafka, Weininger, and Kraus in wealthy or bourgeois, non-Jewishly-observant homes in Prague and Vienna, all were reacting, Kurzweil argued, to the same fundamental absurdity of modern Jewish life—that of a people that pretended to know, and to teach its children, why it should continue to exist when the reasons given by it made not the slightest sense. Whether taking the form of a hidebound Orthodoxy in the East that had exhausted its creative potential, or of a liberal Judaism in the West that paid empty lip service to an abstract ethical mission, these reasons struck an honest mind as delusory if not hypocritical and led in some cases to a revulsion at one’s Jewish roots and at oneself for being attached to them. Brenner, Kafka, Weininger, and Kraus, wrote Kurzweil, all shared the view that Judaism had “ceased to be a living religion” and had even become “diametrically opposed to every religious faith worthy of its name.” And while all saw the logic of a secular Zionism that sought, as a way out of this dilemma, to redefine Jewishness in purely national as opposed to religious terms, all saw its illogic too, since such a Zionism, as Weininger put it while conceding its “nobility” of purpose, was “the negation of Judaism.” To seek self-perpetuation in self-negation was only to compound the absurdity.

There may be some point in associating Brenner with such figures, especially with Kafka, who, besides being personally attracted to Zionism and more Jewishly knowledgeable than either Weininger or Kraus, had a lifelong relationship with his parents that bore a resemblance to the young Brenner’s with his. (There is a parallel between Yirmiyah Feierman’s dream of being crushed by his father and the end of Kafka’s story “The Judgment,” in which a son drowns himself at his father’s command.) Yet as Kurzweil was the first to admit, the analogy is at best partial. A product of the shtetl like Brenner was incomparably more steeped in his Jewishness than was Kafka (who learned some Hebrew as an adult and even read Brenner’s Breakdown and Bereavement in it), let alone Kraus or Weininger. Brenner’s Jewishness was whole as theirs was not; nor was it possible for him to conceive of his life, as did they, in terms of a struggle to overcome the Jewish side of him, since he had no other side, no external vantage point of Germanness or Europeanness, to conduct such a struggle from. Whatever love he felt for himself or for others came, like his hate, from within his Jewishness—and nowhere is there more love in his fiction than there is for the character of Aryeh Lapidot in From All Sides.

You can read Part II of this essay here.

More about: Arts & Culture, History & Ideas, Israel & Zionism, Proto-Zionist Writers, Yosef Hayyim Brenner