Debates over the quality of Jewish culture in the United States—books, film, art, music, museums, you name it—often boil down to an unmodulated choice between full-throated celebration and bitter lament. Take, as a recent case in point, reaction to the opening of the National Museum of American Jewish History in Philadelphia, whose displays express the often explicit premise that Jewish contributions to American arts and culture constitute a triumph not only for American society but for the future of American Judaism. Enthusiastically embracing this trope, many reviewers duly praised the museum as another sign of Jewish cultural vitality, of the successful weaving of Jewish ideas and traditions into the modern American fabric, and of the endlessly metamorphic capabilities of Judaism itself. Mourners, by contrast, saw the artifacts on display, with their wispy and sometimes barely visible traces of ethnic identity, as symptoms of Jewish illiteracy and further evidence of a community rapidly undergoing dilution and loss.

Of course this dichotomy, like all dichotomies, fails to reflect the full complexity of the phenomenon. As one who usually finds himself in the camp of the mourners, I confess to moments of (selective) delight in the cultural achievements of American Jews. My own lament is less a funeral cry than an abiding sensation of hunger and frustration: the cultural bandwidth is so narrow; so much more could be imagined, created, and enjoyed. I especially object to the celebrators’ complacent readiness to applaud the mediocre or the manifestly cheesy, whether it be the latest allegedly highbrow Jewish novel or the latest work of Jewish children’s literature.

It’s the last-named area that I want to focus on here.

Every year, a new crop of books appears, much of it poorly conceived, substantively shallow, reeking of chicken-soup nostalgia. There are exceptions, of course, but vanishingly rare are gems of the caliber of, for example, Deborah Pessin’s Aleph-Bet Storybook (1946) or Isaac Bashevis Singer’s Zlateh the Goat (1966). Only occasionally will a new book deviate by combining decent illustration with, say, a reworking of a less-well-trod rabbinic midrash or some off-the-beaten-track material about Israel.

For the most part, we get a stream of Judaism Lite running in all too predictable channels: cartoon animals teaching holiday basics in stilted rhymes, an overrepresentation of sentimental grandparents (to the frequent exclusion of parents), and shtetl-and-steerage depictions of New York’s Lower East Side as the Sinai of American Judaism.

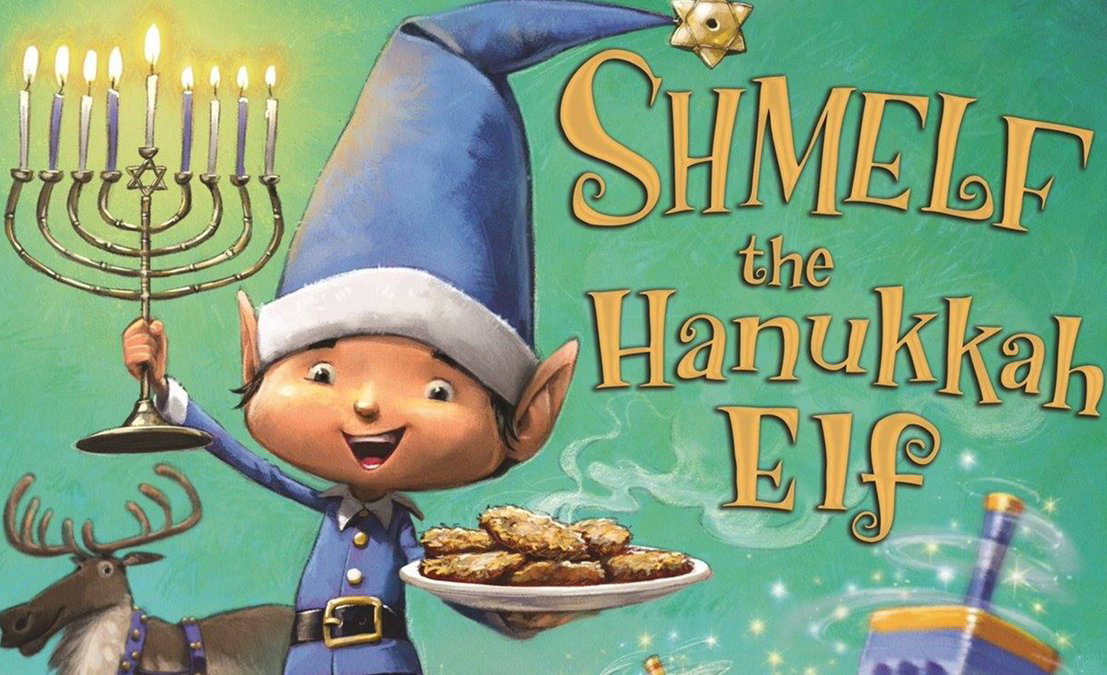

So low have things sunk that a particularly tacky new book, Shmelf the Hanukah Elf—in which one of Santa’s elves imparts the lesson that Hanukah can be just as much fun (or at least as lucrative) as Christmas—has actually sparked a mini-outcry, with critics deriding its supposed cultural insensitivity and shoddy rhymes. Yet Shmelf is not notably more shallow or poorly written than most of what gets served up year after year, like unheated leftover latkes, to young Jewish readers.

Recently, and not for the first time, I noticed on Facebook a group of parents decrying the current offerings for their children. Their complaint centered, as is so often the case these days, on the PJ Library, an organization created a decade ago by the Harold Grinspoon Foundation that sends children’s books, free of charge, to Jewish households. Many people (including relatives and friends of mine) greatly appreciate this service, in some cases because it saves them the expense of purchasing the books themselves, in others cases because it introduces them and their children to Jewish content with which they would otherwise be unfamiliar.

The parents on Facebook were different, being among the minority who have come to dread the arrival of the monthly PJ Library selection. (Participants sign themselves up for the program, and their enrollment is then approved by the local Jewish community.) These mothers and fathers, who tend to be both knowledgeable in matters Jewish and serious about the books in their house, soon find themselves hiding the deliveries from their undiscriminating children. The fault, I hasten to add, is not that of PJ Library, which doesn’t write or publish the books but only disseminates them. Also, some educated families have recourse to the Hebrew-language Sifriyat Pijama B’America, a PJ Library spinoff intended for Israelis resident in the United States and featuring classic Israeli children’s books. But what can you do with yet another variation on Bubbe and the Magic Gefilte Fish or Danny Dinosaur Learns about Passover? (The titles are my own invention; examples multiply.)

The middling or lower than middling quality of so many books published for American Jewish children is all the more striking given the contributions of Jews to American children’s literature in general. But the names of, for example, Arnold Lobel, Lore Segal, Stan Berenstain, and Maurice Sendak do not appear in the PJ Library canon. And for an understandable reason: however redolent their books may be of urban roots, immigrant marginality, and an ethnic sensibility, they have less to do with Judaism than with Jewishness of a free-floating and often indistinct kind.

Still, this doesn’t answer the question of why children’s books that do make their Judaism explicit seem merely to confirm the mourners’ case for the narrowness and cultural improverishment of American Jewry writ large. Why the incessant return to Ellis Island and the mythified shtetls of Eastern Europe; why the omnipresent zaydes and bubbes; why, in the case of books written for older readers and teens, the dominating presence of the Holocaust and the Pavlovian enthusiasm for American-style “social justice”? (I except the books produced by the Orthodox world, which are more soaked in Jewish tradition and Jewish observance if no more distinguished as literature.)

Admittedly, part of the challenge for children’s literature of any sort is to avoid programmatic tendentiousness, a surefire killer of readerly charm. For books whose purpose is specifically to teach aspects of Judaism, especially those marketed to American Jewish families in which parents are often learning the basics along with their children, this presents an unavoidable and all but insurmountable hurdle. Imagine a Goodnight, Moon in which Margaret Wise Brown was obliged to devote pages to explaining what a moon is.

But such constraints do not suffice to excuse the constricted horizons and desiccated imagination of authors and publishers content with manufacturing wading pools when nearby oceans of material are there for the trawling. The global span of Jewish culture, the treasures of the textual tradition, the variety of Jewish sensibilities: these remain largely untouched in favor of recycled Americana, a children’s Bible that stops with Noah’s ark, calendar of never-ending Hanukahs, and liberal pieties. Nor are older readers and teens better served, being instead denied a shelf of modern classics suitably tailored to their level and being left ignorant, even in translation, of books read by their Israeli cousins.

The possibilities of illustration, too, crucial for so many children’s classics, remain barely explored. Where is an illustrated children’s book in which images, layout, and typography might visually enact the delicious intricacy of classic Jewish texts? Where is the Jewish Peter Sis, the Czech-born illustrator whose children’s books on such subjects as Galileo, Prague, and his own childhood under Communism are marvels of lush, eye-filling eloquence?

Anyone seeking a perfect metaphor for the limitations of Jewish children’s literature will find one in the fact that PJ Library makes available not one or even two but three different books based on the Yiddish song, Hob ikh mir a mantl (“I have a little coat”). The garment in this anonymously written ditty gets progressively retailored as it wears out, turning from a coat to a jacket, then to a vest, a scarf, and so forth. Though the great Yiddish poet Kadya Molodowsky published a version of the song for children in the 1930s, I suspect the real inspiration for these English books lies in recent folksong renditions.

These are not bad books. All three are nicely executed and have been justly honored. Phoebe Gilman’s Something from Nothing (1993), set in Eastern Europe and illustrated with careful fidelity to shtetl architecture, won Canada’s Ruth Schwartz award. Simms Taback’s Joseph Had a Little Overcoat (1999) was an honorable mention for the Sydney Taylor award, a prize given annually by the Association of Jewish Libraries and named after the author of the All-of-a-Kind Family books—another rare classic. In an innovative touch, Taback’s version uses cutouts so that each retailoring of the coat can be seen through the previous page.

But the key to the appeal of the recycled coat is made most manifest in the third exemplar: My Grandfather’s Coat, written by Jim Aylesworth, illustrated by Barbara McClintock, and last year’s winner of the Taylor award. This deftly illustrated version maps the familiar story onto four generations of an American Jewish family, beginning with the great-grandfather as he appears on ship deck approaching Ellis Island at the turn of the 20th century. Over the years, the coat becomes worn, frayed, and torn; when it can no longer serve, its tatters are passed down through the generations as a symbol of the indestructible endurance of Jewish identity. On the last page, the granddaughter, now a mother herself, is shown reading this very book to her son, explaining that at last there was

nothing left at all of your

great-grandfather’s handsome coat—

no there was nothing left at all.

Nothing, that is, except for this story.

The coat has disintegrated, but the story lives on. At this point, a reader may be reminded of the well-known ḥasidic tale about Rabbi Israel of Ruzhin. Several generations removed from the Baal Shem Tov, the founder of Ḥasidism, Rabbi Israel lacks the master’s knowledge of how to perform the elaborate mystical ritual that will empower him to intercede with heaven on behalf of his congregation. As the historian Gershom Scholem recounts the tale:

Rabbi Israel would say: “We cannot light the fire, we cannot speak the prayers, we do not know the place, but we can tell the story of how it was done.” And, the story-teller adds, “the story which he told had the same effect” as the rituals of the generations preceding him.

It is a comforting story, and extollers of American Jewish culture will see in it validation of their confidence in each new generation’s ability to reshape and preserve the materials of the past. Yet it is also a story of loss, of what Scholem calls “the decay of a great movement.” In this it symbolizes too much of American Jewish culture and of that culture’s celebrants: making do with smaller and smaller scraps of immigrant fabric, all the while reassuring oneself that this threadbare nostalgia constitutes a tradition.

More about: American Judaism, Arts & Culture, Children, Children's books