A few months ago, a highly regarded expert in medieval manuscripts approached me with a request to become involved in a then-secret mission. Sandra Hindman is a scholar who—through her Les Enluminures galleries in Paris, Chicago, and New York—aids and guides libraries, institutions, and private individuals in acquiring some of the best and last-surviving products of medieval illuminators and their workshops. To this end, she has issued a series of meticulously researched catalogues describing and interpreting such manuscripts. Although it’s unusual for her to devote one of these catalogues to a single manuscript, this one, Hindman felt, was worthy of the attention. Would I have a look?

I would indeed. A few days later, my assistant Gabriel Isaacs and I set out for Manhattan’s Upper East Side expecting to be shown a charter, a loan contract, a Bible with some Hebrew glosses or annotations, or perhaps a Book of Hours depicting Jews in particularly vicious caricature. Little could we have guessed what awaited us: one of the very few high-medieval Haggadahs still in private hands, and a supremely fascinating one.

I was enthralled, on many counts: by, to be sure, the extreme rarity of this beautifully written and exquisitely illustrated manuscript, and by the air of mystery with which Hindman presented it. But, most of all, I was intrigued by the iconography, the manner in which images in this Haggadah told so many stories: of the biblical exodus; of the contemporary world of its obviously very wealthy patrons; of a particular household in a discrete place and at a specific time in history; and of the dream of a future redemption for the Jewish people.

Now that the Lombard Haggadah, as we ended up calling the manuscript, has been briefly on public display at the Les Enluminures gallery in New York—and will in the future be available in a sumptuous facsimile volume complete with explanatory articles about its art, its iconography, and its historical context—I’d like to fill in a bit of the background and then to share what I personally regard as some of the work’s most captivating aspects.

The Lombard Haggadah was last on public exhibition at the 1900 World’s Fair in Paris, when it belonged to a French family. In 1927, the great Jewish bibliophile Zalman Schocken acquired the manuscript in London.

Quite aside from the Haggadah’s singularly entrancing value as a Jewish object, it is a truly remarkable work of art—one whose 75 watercolor paintings, occupying the margins of almost every page, superbly capture the elegant pictorial language of the Gothic International style. Artistically, it can more than hold its own among the most beautiful works of its time.

The Haggadah was created in Milan, Italy in the late-14th century. Commissioned during a period that saw a wave of northern European Jews immigrating into Lombardy, it was produced in the circle of Giovannino de’ Grassi (d. 1398), a famous master builder, sculptor, and illuminator who flourished under the patronage of the noble Visconti family. One member of that family, Duke Gian Galeazzo Visconti, is known to have especially welcomed the Jewish newcomers.

Responsible for a great deal of the planning and decoration of Milan’s famous cathedral, de’ Grassi and his workshop also produced a remarkable sketchbook of naturalistic drawings—itself a certified masterpiece of Renaissance art—and the equally valuable Tacuinum Sanitatus, recording aspects of daily life and seasonal occupations (“Labors of the Months”) among both nobles and peasants.

And this brings us directly to the wonderful—if somewhat perplexing—iconography of the Lombard Haggadah. Adopting the language of the Passover season, I can put the relevant question this way: what makes this Haggadah different from other Haggadahs? Although there are many ways to answer to that question, here I’ll focus on a few elements in particular.

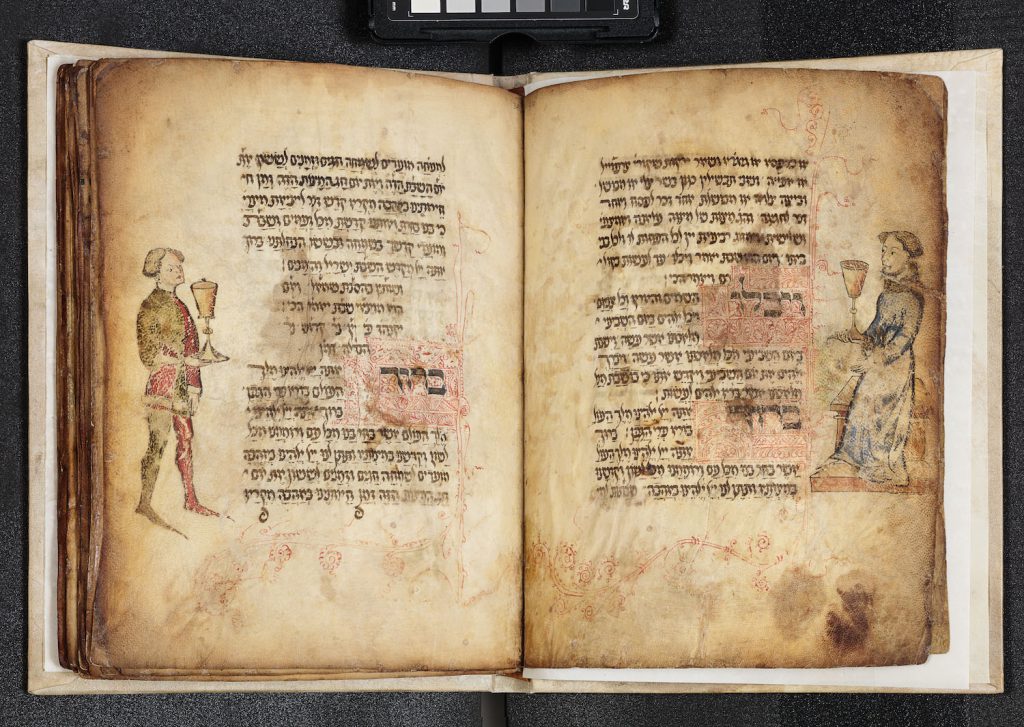

To begin with: the basic premise of the Passover ritual lies in the commandment to remember, and to reenact, in some embodied way, God’s freeing of Israel from bondage. Why, then, in this Haggadah, do we see so many servants, often decked out in livery?

Should not the householder himself—living, obviously, in enough freedom to be able to commission so lavish a manuscript—be the one performing the rituals? More specifically, is it appropriate for a servant to be holding the maror, the bitter herbs that are the seder-night symbol of the bitterness of Egyptian servitude?

And why is this servant accoutered in livery while his colleagues serving wine and matzah are not?

The livery I am referring to is a parti-colored outfit that historians call “mi-parti” (that is, divided vertically down the middle). In the Lombard Haggadah, those wearing it can usually be identified as either servants or Gentiles—or both.

(Historically, I should note in passing, mi-parti was not only the livery of servants. It was adopted as well by fashionably dressed Christian nobility—a manner of “slumming,” in, for example, the way that Marie Antoinette and her court played at shepherds and shepherdesses in silk and damask, or in the way that workingman’s dungarees have in our own times morphed into “designer jeans” selling for hundreds of dollars a pair.)

To complicate matters, even some Jews in the manuscript wear this same garb—like the figures of Abraham and his son Isaac seen on the road to their fateful appointment on Mount Moriah. True, in their case, the dress might signal conformity with a halakhic ruling permitting travelers to camouflage themselves as protection from anti-Jewish violence. In possible support of this idea, when father and son arrive at their destination and are “performing” once again as Jews—in fact, as the archetypal Jews of religious drama—they revert to normal clothes of what we might call “householder” length.

In other cases, though one struggles to resolve apparent contradictions. This is important because several features of both the Passover preparations and the seder ritual itself have traditionally been considered the prerogative of Jews alone, involving actions not to be performed by Gentiles. Since traditions vary from place to place and from time to time, we can only conjecture as to the precise practice of the community in which this manuscript originated and which it could reasonably be thought to reflect.

But let’s consider a few examples.

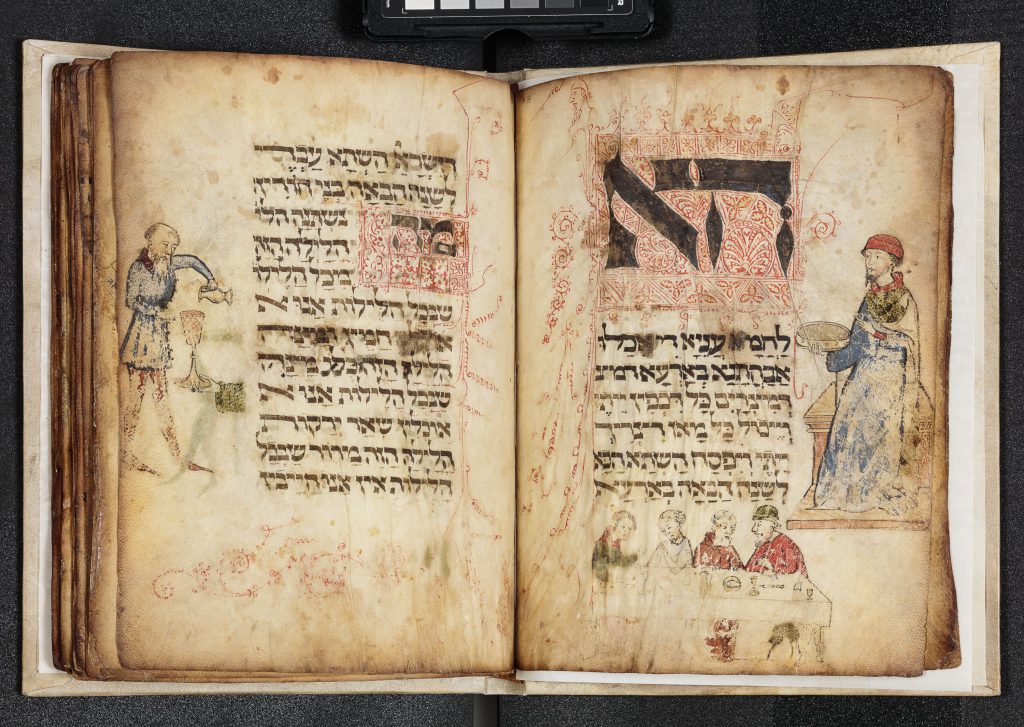

In our manuscript, persons performing certain actions that could potentially be compromised by the involvement of non-Jews—pouring wine, kneading the dough for matzah, holding finished matzah—are not depicted in mi-parti, thereby indicating, perhaps, that these persons are Jews.

In other cases involving ritual foods where it was less critical for a Jew to be involved—holding the bitter herbs, putting matzah into the oven to be baked under the supervision of Jewish women—the figures do wear mi-parti garb, indicating, perhaps, that they are Gentiles.

So far, so good. But now take the handling of wine: an especially sensitive issue in Judaism. In our manuscript (folio 5), a bearded, bald servant pouring wine out of a jug into a cup held by a disembodied hand is depicted without mi-parti garb—and may thus be intended to be “read” as a Jew.

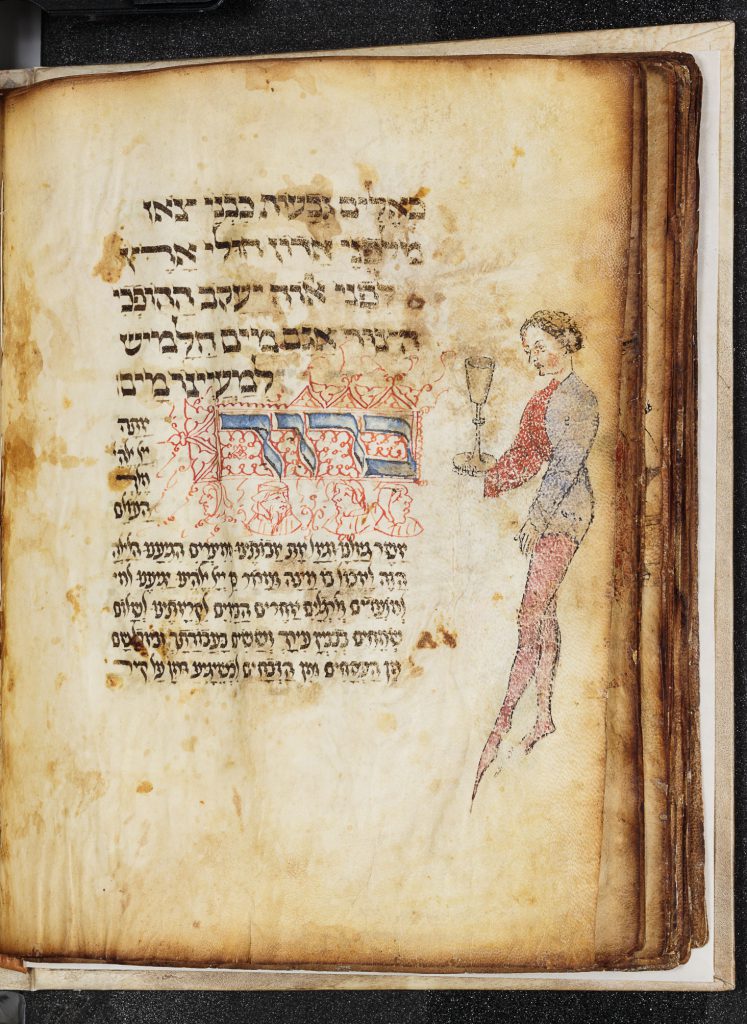

Elsewhere (folio 3), in an interesting twist, a young Gentile servant in mi-parti is shown offering wine in a covered rather than an open cup; is the cover, perhaps, intended to mitigate the fact of his involvement as a non-Jew?

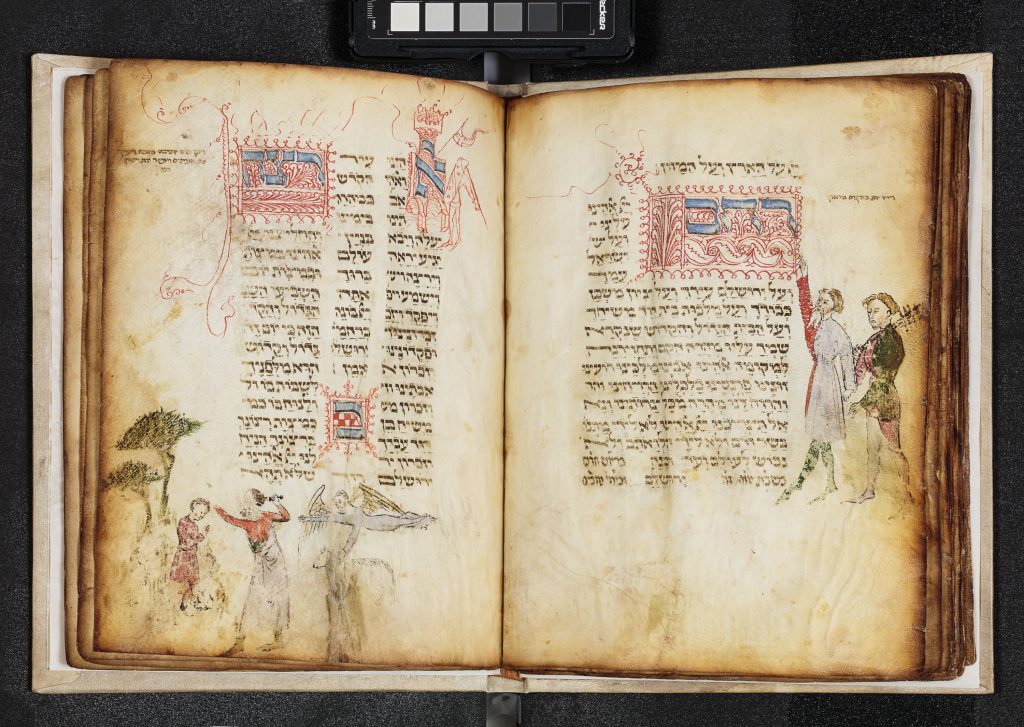

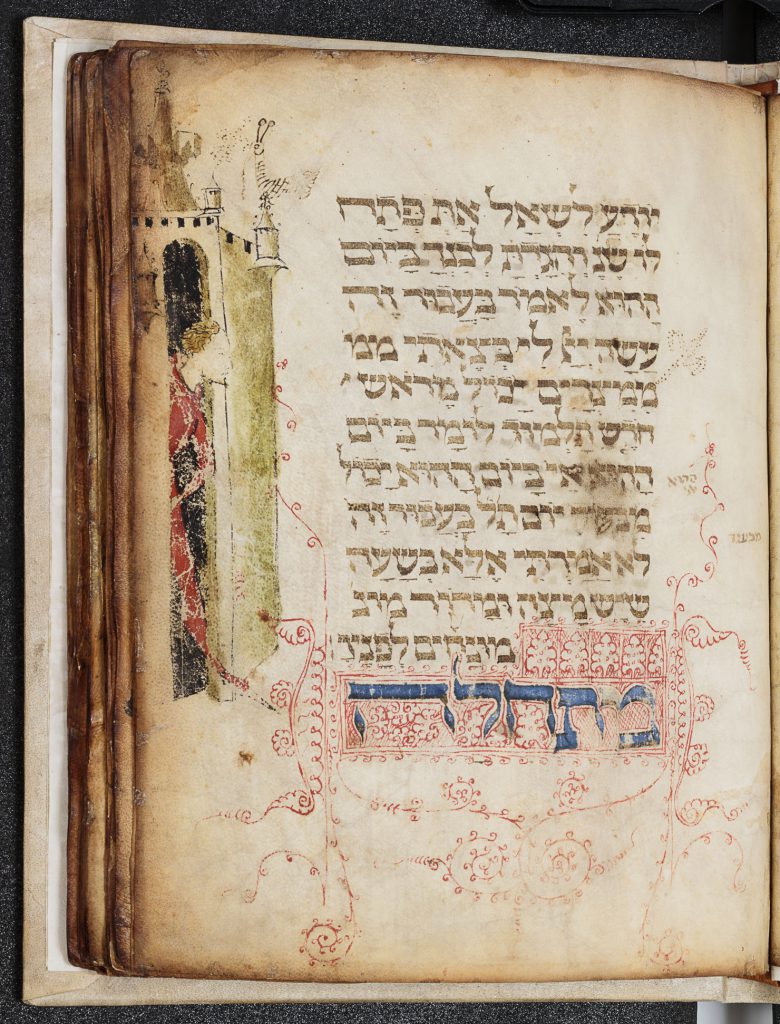

But now to complicate matters still further, there are, apart from the Abraham/Isaac scene, two other instances in which an ostensibly Jewish character is also depicted in mi-parti. The first appears on the recto side (reading Hebraically from right to left) of folio 28.

A wild-eyed man with disheveled hair is shown leaving Egypt (represented as a crenellated fortress) holding a palm branch signifying “victory,” “triumph,” or “freedom.” He has a long-nosed aquiline profile and bulging eyes very similar to the depiction of the Gentile servants in mi-parti energetically pounding the ingredients for ḥaroset (a chutney-like ritual food resembling and recalling brick mortar) on the folio directly opposite.

This figure appears in connection with the passage “When Israel went forth from Egypt” (Psalms 114:1), and he enacts an event described in that text as occurring in the historical past. One understanding of the people of Israel at the Exodus is that they were intermingled with a “mixed multitude” (Exodus 12:38) and as yet unpurged of the remnants of slave mentality and Egyptian idolatry. According to this view, it was not until they stood at Sinai that they were—however briefly—purified, before falling once again into the sin of idolatry in the incident of the Golden Calf.

Accordingly, the man shown here is dressed in mi-parti like a servant or a Gentile. In fact, he participates somewhat in each of these categories: he is a servant because he is a slave just emerging from Egypt, and he is a quasi-Gentile because he has not yet been refined by the Sinai experience. Although he bears the palm of freedom, he’s not quite “us” yet. Indeed, the pounding of the mortar-like ḥaroset across the page, which appears with no textual justification, might plausibly be read as a metaphor for the necessary refining process that in both cases will result in the production of material for “building.”

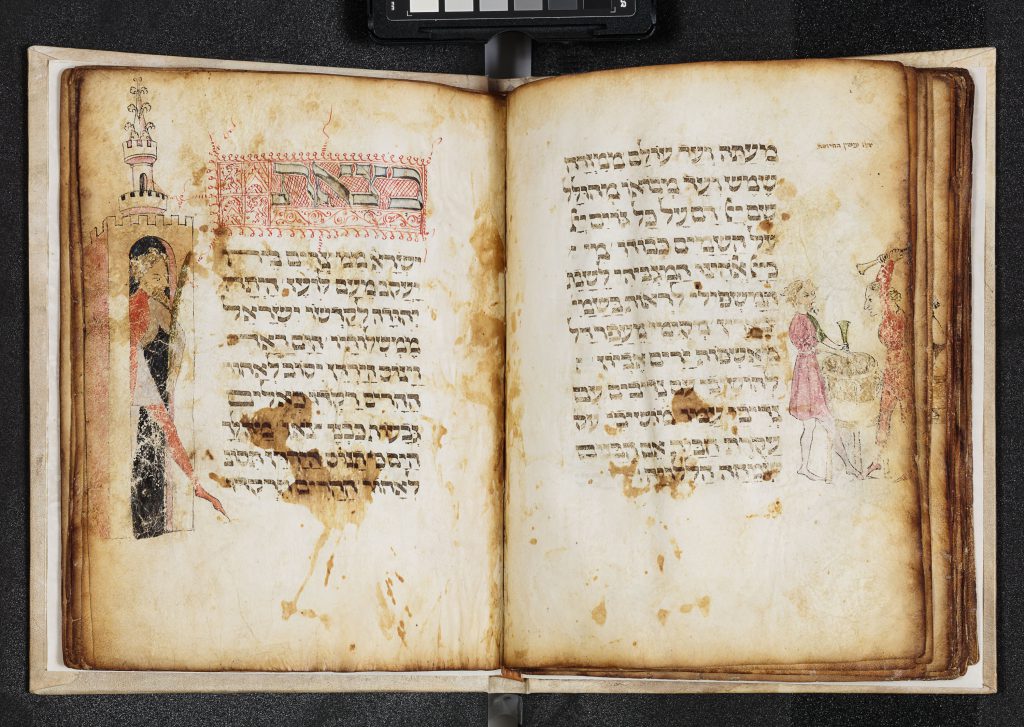

Present on the verso side of the folio depicting our unrefined Israelite is the second intriguing image of another ostensible Jew in mi-parti: a youth raising an uncovered cup in accompaniment to the blessing over the seder’s second cup of wine.

To this young man we’ll return at the conclusion of the essay; for now, let’s turn to more general matters.

Overall, the iconography in the Lombard Haggadah gives the impression of having been chosen less with an eye to conveying a specifically religious or political message than to projecting a glowing image of the work’s patron in his capacity both as a human being and as a Jew.

Although he figures centrally among those engaged in the rituals of the seder, the patron does so frequently as the unseen supervisor and recipient of actions being performed for his benefit and satisfaction by his liveried servants. Thus, on some occasions, we see a servant presenting ritual objects to the unseen patron; once, his hand alone is shown receiving a cup tendered by a servant who by contrast is rendered in full; at still other junctures he is invited, as it were, to contemplate a mirrored image of himself being served.

This evident interest in seeing himself as the object of his servants’ attentions may also explain the patron’s liking for depictions of peasants enacting their “labors of the months”: a feature that exists in no other known Haggadah. Like Jean Duc de Berry in the Très Riches Heures, the most celebrated of Gothic illuminated manuscripts, he seems to regard himself as the sort of grand lord who sets his clock by the daily activities of his servants and marks the seasons by the field labors of his peasants. On Passover in particular, as if to emphasize the contrast between himself and his ancestors, this establishes him as an individual of substance, no longer a slave himself but, to the contrary, a free man being served by others.

Such images begin with a preliminary scene of servants boiling vessels in early preparation for Passover, a setting also suggesting that, in parallel to “secular” labors of the months, there are, in a Jewish context, labors of the month—as Nisan, the Hebrew month in which Passover is celebrated, is known. Additional such scenes include the drawing of water, the preparation of ḥaroset, and the baking of matzah.

Of course, in historical reality, the patron’s status as a “free person” (a ben ḥorin, in the language of the Haggadah) was somewhat illusory. However wealthy, he was still a Jew, and so, unlike the Duc de Berry, could never truly be a “grand lord.” It is in keeping with his consciousness of this ambiguous status that the patron’s enjoyment of his luxury is pictured as mainly passive or quietist rather than activist in tone—as we may glean from the Passover scenes that are not illustrated in this manuscript: always an interesting litmus test for any given manuscript.

Thus, the Lombard Haggadah contains no scenes of the first, hasty Passover meal, the one prepared and eaten while the Israelites are still in Egypt. Nor does it depict their crossing the Sea of Reeds, or their miraculous salvation from the pursuing Pharaoh and his host. Nor, unlike the joyous anticipatory depiction in the Birds’ Head Haggadah (southern Germany, early 14th century) of the rebuilt city of Jerusalem and the Third Temple, is there any such image here, just as there is no depiction of the Passover sacrifice being offered in that restored Temple as in the Golden Haggadah (northern Spain, circa 1320).

It is as if the principal markers of the first great political act of the Jewish people—the liberation from bondage, the overthrow of Egyptian hegemony, the subsequent striking-out of the people armed and in their numbers for the Land of Promise—suggested analogues too politically heady for the Jews who commissioned the Lombard Haggadah, prosperous and comfortable though they were in their own lavishly cushioned exile.

This leads me to two further observations about moments in the Lombard Haggadah that stand out amidst its delightful richness of design and iconography.

In this manuscript, as I’ve already hinted, we find not one but two “mirrors” of the patron’s self-image. On the one hand, he is, or wishes to be seen as, a great and fashionable lord commanding many liveried servants: a man of his world and of his time. On the other hand, even if not deeply learned, like the patron of the Golden Haggadah, or political, like the patron of the Rylands Haggadah (Catalonia, mid-14th century), he is a Jew deeply committed to the timeless re-enactment of the exodus from Egypt.

And, superficially at least, there is no contradiction here: he is, or projects himself as being, completely at home in both worlds. In this sense, he was probably like many of his class and time. But, unlike them, he left us a mirror reflective not only of these dual values but of the inescapable tension between them.

There is a visualization of this tension in the Haggadah itself. Earlier I mentioned the male figure in mi-parti shown exiting a building intended to represent the “prison house” of Egypt. As it happens, there is another such image of a similar male figure exiting the fortress.

This one is shown as a dignified, eager young man in the long surcoat of a householder. The image is linked to the passage in the text of the Haggadah about the “four sons”—here, in particular, the fourth son, the one “who does not [yet] know how to ask” about the meaning of the Passover observances. To him, the father’s prescribed response is to say: “It is because of what the Lord did for me as I went forth [b’tseyti] from Egypt” (Exodus 13:8).

Strikingly, the Egypt-exiting action of this “son who does not know how to ask” is presented pictorially as tentative and provisional—he is shown with only one foot emerging from the edifice of Egypt. He is, in other words, in the process of leaving, dipping a toe, so to speak, into redemption, with the continuation and possible endpoint of his action implied but not yet seen.

That image is a visual evocation of the Hebrew word b’tseyti— as I went forth (rather than “when” or “after” I went forth). But it also makes a theological point, and in so doing opens a window into the mind of the patron of this manuscript.

Redemption—say both the text and the image of a man emergent but not yet fully emerged—is a process that occurs in God’s good time, and cannot be hurried. One must be ready for the next redemption to occur in the flash of an eye, as it once did in Egypt. But since no one knows the moment of its coming, it is incumbent to be patient about its belatedness while simultaneously assured of the inevitability of its arrival.

In a world as yet unredeemed, this is a lesson worth taking from a book that, in this crucial sense, mirrors both its time and our own.

And that, in conclusion, brings me back to the ambiguous image of the youth in mi-parti raising an uncovered cup on the verso of folio 28.

As we’ve seen, his clothing marks him as a Gentile and/or a servant, but his action—holding an uncovered cup in preparation for the blessing and consumption of the second cup of wine at the seder—seems to contradict this by distinguishing him as a Jew. In truth, he is both and all of these things simultaneously. For this figure, too, which I regard as one of the most important in the entire iconography of the Lombard Haggadah, likewise straddles past and present.

Hovering over and throughout this beautiful book is a cognizance that the exile is not over, that Jews in early-15th-century Lombardy are not yet fully redeemed, that, in some sense, the moment of leaving Egypt with the residue of idolatry clinging to oneself has been unreasonably extended.

The owners and audience of the manuscript might, on the one hand, have indeed thought of themselves as erudite and worldly householders and patrons of beautiful works of art like this Haggadah—“wise sons,” all. But at the same time, they might well have felt oppressed by their people’s long experiences of enslavement and their own necessarily uncertain situation, and in this they could relate to the image of the man in split clothing who leaves Egypt with the stain of hesitancy on his body and in his conduct. Some of them might even have felt so spiritually downcast that they empathized with the “son who does not know how to ask” the right questions.

Nonetheless, they were confident enough as Jews to lift the goblet of sanctified wine and to testify that God would ultimately redeem them from their present, bearable exile just as their ancestors had been redeemed from their unbearable one. The ambiguous and ambivalent split-clothing image of the youth lifting the cup thus likewise confirms the foundational principle of this Haggadah’s very existence—the interweaving of the experience of freedom with the inescapable, still only partially free reality of Jews even as powerful and wealthy as the patrons who oversaw the manuscript’s creation.

In this perspective, it is no accident that the ritual act illustrated by the youth in mi-parti is the Blessing of Redemption that is recited over the second cup of wine: the blessing that thanks God for having “redeemed us, and redeemed our ancestors from Egypt, and brought us on this night to eat matzah and maror.”

Us and our ancestors. Together, as one. On Passover eve, the youngest child observes, “How different is this night from all other nights!” For Passover night is the night on which even the wealthy, reclining in luxury, consume the bread of poverty and the herbs of bitterness. And they do so in order to tell, in ancient words, a beloved story that they then retell, enrich, and augment with their own lived experience. In this precious manuscript, in fresh, new pictures, the ancient story is combined with a contemporary one, and the book containing these ancient words becomes at once a mirror of “this time”—ha-zman ha-zeh, in the rabbinic phrase—and all time.

More about: Arts & Culture, Haggadah, Passover, Religion & Holidays