For the nearly five million annual visitors to the Sistine Chapel, the “main events” are the ceiling painting of the creation of Adam and the altar-wall painting of the Last Judgment, the two gigantic masterpieces by Michelangelo. But when I visit this jewel-coffer of a space, I find myself quietly gravitating to one of the benches that line its sides.

From that marginal perch, my focus is less on Michelangelo’s central works than on the chapel’s long north and south walls, which display the less inventive though no less magnificent work of Perugino, Botticelli, Ghirlandaio, Rosselli, and d’Antonio. In depicting episodes from the life of Moses (north) and of Jesus (south), these paintings offer Christians the opportunity to reflect on how their faith conceives the latter’s ministry as the fulfillment and completion of the former’s mission.

As a scholar of religious art in general, I’m of course interested in how this exegetical move (called “foreshadowing” or “typology”) plays itself out visually. But as a Jew with an interest in the depiction of Jews in art, I’m drawn more to the wonderful portrayals of the life of Moses (including the panels showing him receiving the Torah and the punishment of Koraḥ and his band of rebels), rendered in elegant Renaissance settings that mix classical architecture, perspective, and modeling of figures with contemporary Italian fashions. It’s all densely conceptualized, gorgeously designed, and beautifully executed.

Over the years, one panel in particular of the Moses cycle has gripped my attention: the group of scenes on the north wall, at the end of the chapel farthest from the altar, depicting Moses’ last acts and death. (Predictably, these are paralleled on the opposite wall by scenes depicting Jesus’ last acts and death.)

The 16th-century artist and art historian Vasari confidently ascribes this panel, painted in 1481-2, to Luca Signorelli, despite the fact that Signorelli’s name is not included in the relevant contemporary documents. Today’s expert consensus differs somewhat, holding that Signorelli painted only the dynamic figures, while the painting’s more static figures, and the background landscape, should be attributed to Bartolomeo della Gatta (who is also absent from the documents).

Four scenes are depicted in this painting, which measures roughly 18½ by 11½ feet. On the right, Moses recapitulates the Torah before the people of Israel; at his feet is the open ark displaying the two tablets of the law and the jar of manna. On the left, he hands over leadership to Joshua, placing his fabled rod, in the form of a scepter, into the hands of the younger man. At center in the background, an angel shows Moses the land of promise—which he will never reach—from Mount Nebo, after which Moses descends the mountain, leaning heavily on his rod. Finally, at top left, his corpse is laid out on a white sheet, naked but for a white loincloth, arms at his side, while the Israelites mourn; Moses’ head is flung back as in a death agony, his beard jutting heavenward, where only clouds appear. There is no sign of the presence of God.

The biblical episodes depicted in this last scene draw upon the parashah of Vayeylekh (Deuteronomy 31:1-30) and upon Zot Ha-brakhah (Deuteronomy 33:1-34:12), the final parashah in the Torah, read on the festival of Simḥat Torah which this year falls early next week. The biblical narrative is tremendously moving.

At the opening of Vayeylekh, Moses announces to the people:

Today I am one-hundred-and-twenty years old, and I can no longer go out and come in. Moreover, the Lord has said to me, “You shall not cross over yonder Jordan.” (31:2)

There’s something both wistful and poignantly melancholic about this declaration; it tells of an astounding longevity, replete with all the monumental struggles and achievements of a life fully lived but simultaneously somehow tainted by failure and, at the end—in that “You shall not cross over”—the culminating unfulfillment of a destiny. Reading and hearing these somber words, many Jews today cannot help being struck by the realization that yet again, approaching the end of the yearly reading of the Torah, they themselves have come to the end of another passage marked by both blessings and curses, successes and unrecoverable failures. I’m not the only curmudgeon who habitually tears up at this reminder that Moses, at least, enjoyed an exceptionally long life; for most of us middle-aged and older mortals, a briefer span remains to us than what we have already squandered.

And then, in the Torah’s last chapter, comes the somber finale:

So Moses the servant of the Lord died there, in the land of Moab, at the command [literally, “by the mouth”] of the Lord. He buried him in the valley in the land of Moab, near Beth-peor; and no one knows his burial place to this day. (34: 5-6)

There’s so much to unpack here: from the seemingly superfluous “at the command of the Lord” (does not every death occur at God’s command?) to the peculiar and grammatically ambiguous “He buried him.” (Who buried whom?)

Rabbis and traditional exegetes alike have noted these problems and woven beautiful things from them. “He” buried “him”: God personally, rather than the angel of death, relieves Moses of his soul. “By the mouth of the Lord”: God does so with great tenderness—in a “death by a kiss,” the paradigm of a good death and the privilege of only a select few. The Midrash, after a lengthy imagining of Moses’ protests at being disallowed entry into the land—his not-to-be crowning triumph—visualizes the Almighty’s tender response: “and He drew out his soul with a kiss of the mouth.”

Naturally, it interests me as a student of art made by and for Jews to consider how these ultimate moments have been treated iconographically. What sort of exegesis, what construal of meaning, is spun by the specific images made or commissioned by Jews to illustrate this overwhelmingly dramatic scene?

Faced with such an image, a traditional art historian would begin by placing it against the backdrop of the biblical text, comparing it with and contrasting it to other images of the same scene, collating it and them with various exegetical texts that might have been known by art patrons, and speculating on the circumstances that may have prompted such patrons to commission such a portrayal.

As it happens, I’m not a traditional art historian—which in this case is a lucky thing. For, however much I might wish to present readers with a sampling of images of the death of Moses from the visual corpus created by and for Jews throughout history, I could not. Images of scriptural incidents much less visually dramatic than this one, and certainly less important exegetically, abound. But no image—none whatsoever—exists of this one.

How, then, to write about an artistic motif from Scripture for which there is no art? Obviously, by trying to explain why it is absent. Could the reason be the desire to avoid anthropomorphism? That’s certainly a plausible speculation: showing God kissing Moses would have necessarily involved the depiction of an embodied deity—a distinct violation of the norms of Judaism. And as for symbolic or abstracted substitutes for such a depiction, these would undoubtedly cause considerable confusion for the viewer and in any case would hardly suffice to compensate for the lack.

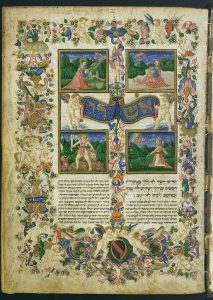

Of course, for every strict rule, even one so ironclad as the prohibition of depicting the divine, there are exceptions. One of them, of Italian provenance, is the opening Hebrew page of a 15th-century book of Psalms. If, then, there were a will to depict a divine kiss and reproduced below, one might think there would be a way—even an anthropomorphic way—of doing so.

But I actually think something different. To me, the clear avoidance or rejection of any such option is not only intentional but constitutes an exegetical move in and of itself.

My argument from silence is this: Moses’ death, in spite of the enchanting literary embellishments of it in the Midrash, is in a certain sense ignominious. By the end of his 120 years, Moses has become a figure larger than life— a God-man, “ish ha-Elohim,” as the book of Psalms terms him (90:1). Yet Jewish tradition tends to eschew the celebration of larger-than-life personages, supermen or superwomen, demigods and other quasi-divine figures—to the extent that the Passover Haggadah includes very little mention of Moses at all or of his role in the redemption from Egypt, preferring, with the rabbis, to make God the savior and hero of the story. Moses is indisputably “this man Moses” (Exodus 32:1).

Indeed, according to the Polish ḥasidic rabbi Kalonymous Kalman Halevi Epstein (1753-1823), Moses, who began his life with so little consciousness of God that he didn’t even know enough to remove his shoes when standing on holy ground, ended his life so impossibly elevated, so supremely placed as a result of his continuous encounter with God, that, as he himself stipulates in the passage I quoted early on, he could no longer “go out and come in.”

Epstein points to the strangeness of that construction: the general way of the world, he observes, is to speak of coming and going, not of going and coming. The shift in normal usage must be significant, and the significance, says Epstein, is this: Moses can go and be on the mountaintop, with God, but he has forfeited the ability to come back and be with the people. Meanwhile, for their part, the people need leaders to whom they can relate; the larger a leader is than life, the closer to God, the more distant he is from the people he both leads and serves.

The light of Joshua, the Talmud tells us, was like the light of the moon compared with Moses’ light, which shone as the light of the sun (Bava Batra 75a). But Joshua had a quality that Moses, especially at the end of his life, lacked. Though Joshua’s own greatness only dimly reflected the greatness of Moses, as a general and a man in connection with his community he was vastly greater than Moses. And so Joshua is appointed to lead in Moses’ stead, and so God draws out Moses’ soul with a kiss and personally sees to his burial.

Can I adduce commentaries or parallels to support my contention of an image missing deliberately? Here are two (equally cryptic) signs, one scriptural, one exegetical.

First, Scripture: “He [God] buried him in the valley in the land of Moab, near Beth-peor; and no one knows his burial place to this day.” Moses’ burial place remains obscure for the specific purpose of preventing it from becoming a shrine, a place of pilgrimage, a site for idolatrous and forbidden worship of a human being as opposed to the true and prescribed worship of the invisible divinity.

Second, exegesis: as I have said, the Passover Haggadah itself—the motherlode of all commentary on the Israelites’ slavery in Egypt, desert wanderings, and entry into the land of promise—almost completely excludes even the mention of Moses. This alone presents an almost exact parallel to the excluded scene of Moses’ death in the iconographic record of art by and for Jews.

Clearly, it is difficult to “prove” anything by means of an argument from silence. But neither can we definitively prove that the creator of any specific artistic image has in mind a specific text that might have influenced the creation of that image. An image is an image and a text is a text—and besides, we have no way of demonstrating what different artists may have known or studied. Their information could have been gleaned, for instance, from a body of general knowledge transmitted orally in traditional communities.

Of course, images of Moses himself have indeed graced Haggadot since at least the 14th century, although none includes the scene of his death. That particular honor, if honor it is, was left to Marc Chagall, who depicts just this scene not in a Haggadah but in his 1956 portfolio of Bible etchings. And with him we may conclude.

Chagall, never one to refrain timidly from anthropomorphizing God, proceeds here in his trademark fashion, which is at once deeply Jewish and indelibly influenced by Christian art. His Moses is laid out like Signorelli’s, not naked but barefoot, not upon a white cloth but dressed in a white robe, the “horns of light” on his head and his staff by his side. As for what is “Jewish” about the image, perhaps it is the figure of God, whom Chagall has reinserted into the clouds that, in the Sistine panel, conspicuously lack any sign of the divine presence. In Chagall’s rendering, Moses raises his hand toward the anthropomorphic deity in a way that may also invoke passages in the Midrash where Moses argues against his death sentence and pleads with God for life.

I cannot imagine that Chagall did not also know how those same passages of the Midrash end. And yet, most significantly, this artist who delighted in evoking the eroticism alike of the Song of Songs and of a drunken bacchanal, who was also capable of rendering the most spiritualized, ethereal, and sublime of kisses (see The Birthday, 1915), here nevertheless stops short of depicting the divine kiss.

So even for this cheeky modern Jewish artist, there remains an emptiness, an absence, or a resistance. What accounts for it? Nothing in Chagall’s art suggests he was aware of what I’ve called the ignominy of Moses’ death. But there may be another reason for his avoidance of the kiss: simply that, in the end, some things remain permanently undepictable. So vast and so deep is their profundity, so vaporous their mystery, that “even if written with needles on the horizons of vision” (to quote the anonymous authors of the so-called Thousand and One Nights), they defy not only visualization but human comprehension.

If ever there were such an unfathomable and undepictable something, surely it would have been the moment in history that sealed the death of this matchless man of God, this nursing father of His fractious, chosen people, this prophet who was lit like the light of the sun.

More about: Arts & Culture, Hebrew Bible, Moses