In a series of repeating images, it is the small and subtle differences that tell the true story.

This week’s spate of violence in and around the Gaza Strip mostly resembles the previous rounds—in 2021, 2019, 2014, 2012, and 2009—in the weapons used by both sides, the lopsided death tolls, and the selectively pious outrage of the self-appointed guardians of global probity.

But there were a few slight changes this time, and they reveal a great deal. The Iran-backed militant group which initiated the crisis last week by threatening an attack on Israel unless a long list of demands were met greatly overestimated its own tactical capabilities and greatly underestimated the operational and intelligence capabilities of its Israeli adversary. It also misread the domestic political situation in Israel and the regional diplomatic situation in the Middle East.

Israel, for its part, still has no effective long-term strategy for dealing with the problem of the Gaza Strip, largely because its elites are terrified of formulating an effective strategy for the problem of the West Bank. But at a tactical level, its handling of the most recent conflagration shows a limited, incremental, but nonetheless crucial process of learning.

After years of relative quiet, Israel was rocked by a series of terrorist attacks this spring. Security services began cracking down on terrorist operatives in the West Bank, with a particular focus on the northern West Bank town of Jenin. During the second intifada, Jenin was a hotbed of terrorist activity, famous in particular for being the point of departure for many of the suicide bombings which were a hallmark of those years. But after a thorough routing by the IDF in 2002, and even more so after Palestinian politics cleaved geographically into a Hamas-dominated Gaza Strip and a Fatah-dominated West Bank in 2007, what was left of the various armed factions behind much of the terror campaign went deep underground.

All this changed in the last two years as the pandemic wreaked havoc on the Palestinian economy and as every faction, inside the ruling Fatah establishment as well as outside of it, had to begin seriously preparing itself for the succession battle that will start the moment the eighty-seven-year old Palestinian president Mahmoud Abbas leaves the scene. Pandemic restrictions meant that the flow of Arab Israelis who sustained the Jenin economy ended, while a dramatic jailbreak of Palestinian militants from a prison just across the Green Line from Jenin galvanized their comrades and increased friction between them and the IDF.

In response to the wave of attacks in March and April this year, the IDF stepped up its raids in Jenin and its environs, rounding up wanted militants in occasionally violent encounters. It was in one such operation in May that the Al Jazeera reporter Shireen Abu Akleh was killed. This was not the only time an arrest operation ended violently. One way or another, a terror network was rolled up, and the wave of violence in Israel cities was blunted.

It was in the context of this ongoing operation that on July 31 security services arrested Bassam al-Saadi, a senior operative of Palestinian Islamic Jihad (PIJ), a jihadist militant organization that is smaller and older than Hamas, and more directly backed by Iran. The organization reacted immediately with threats to retaliate violently, threats which Israeli intelligence took very seriously. In particular, the Israeli authorities expected Islamic Jihad to carry out an attack from Gaza on a target in Israel using anti-tank missiles. Such attacks had already been attempted before. In 2018, Hamas fired an anti-tank missile from Gaza at an Israeli bus on the other side of the fence, destroying it completely. Video of the attack seem to suggest that the attackers waited for the bus to be empty in order to demonstrate how deadly such an attack could be without, at that moment, precipitating a full-blown war.

With this in mind, Israel placed all of the communities bordering the Gaza Strip in a temporary lockdown. Roads were closed, rail service in the western Negev was cancelled, and people were ordered to stay in their homes.

Behind the scenes, PIJ was communicating a set of demands to Israel via Egyptian intermediaries. Israel, it demanded, needed to release al-Saadi as well as another prominent PIJ operative arrested earlier, and it needed to commit itself to limit future counter-terror operations in the West Bank—or else the PIJ would carry out its attack.

This, of course, was a barely modernized form of hostage taking. In the 1970s a terrorist organization would respond to a senior operative’s arrest by hijacking a plane and demanding his release in exchange for the passengers held hostage. Now they could save themselves the hassle of airport delays and hold thousands of citizens hostage to make essentially the same demand.

Why did PIJ think this was a gamble worth taking? They’re not quite so naive as to have seriously expected that all their demands would be met. But they must have believed they could wring some concession out of Israel, especially from such a new and untested prime minister lacking security credentials heading into a snap election as Yair Lapid.

In fact, PIJ could have achieved something quite significant without having a single demand met. The ability to send an entire region of Israel into a full lockdown for three days is a form power on its own, one that would no doubt be exploited in future unless Israel endeavored to make it very costly now.

This was the dilemma facing Prime Minister Lapid as the lockdown entered its third day, as pressure on him was mounting and patience was waning. It was then, too, that the local leadership of PIJ despaired of extracting any more concessions from their “hostage” and decided to carry out the attack they’d been threatening.

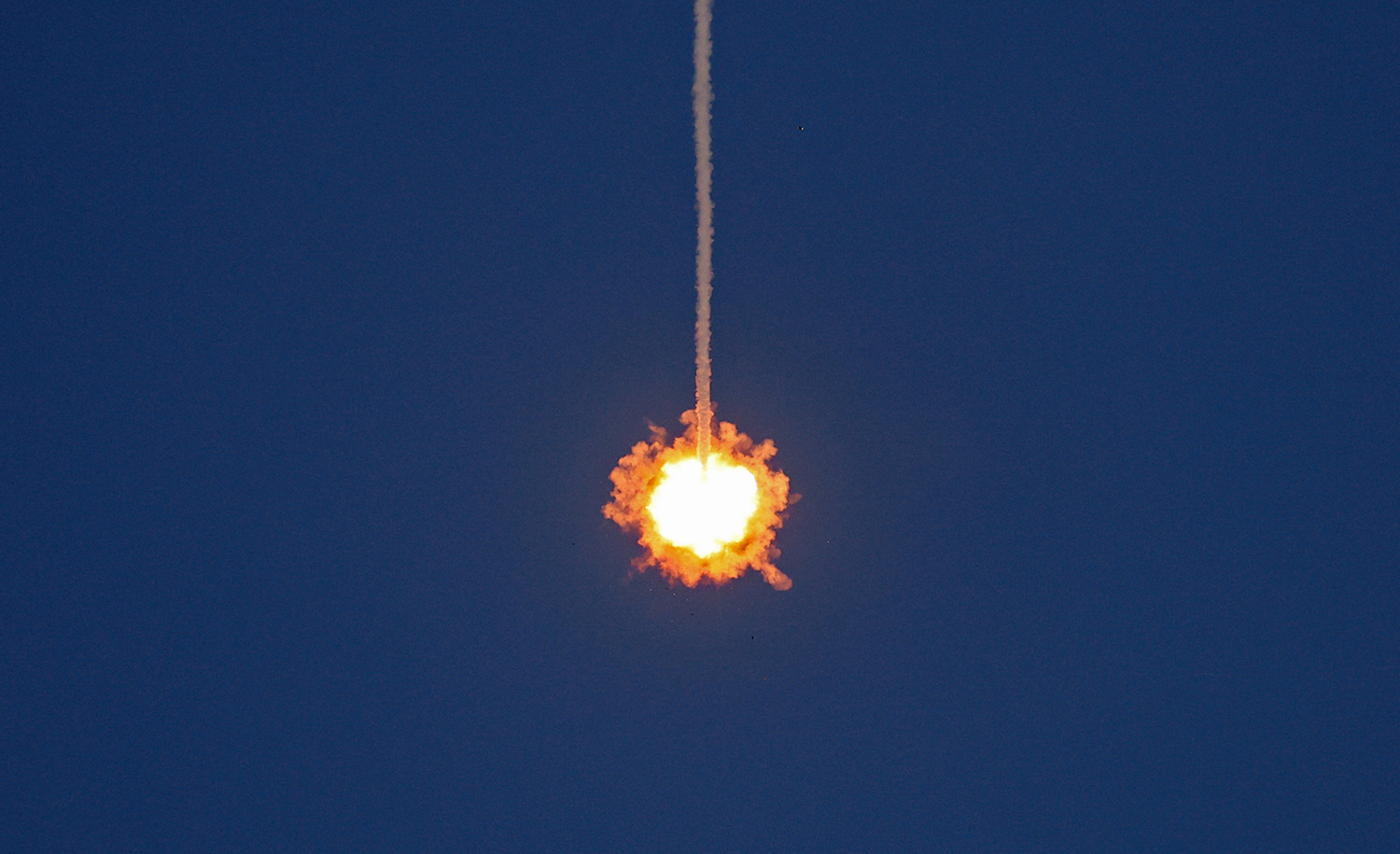

But the attack was thwarted when the cell that was about to carry it out was taken out by the Israel Air Force on Friday afternoon—the same time that a senior PIJ military commander was also targeted by Israeli fire.

Within hours, the organization was firing retaliatory rockets at Israeli cities, which were nearly all intercepted by Israel’s Iron Dome anti-missile defense system. Indeed, over three days of fighting, PIJ managed to fire rockets at Tel Aviv and Jerusalem and most of the Israeli south, but they did not manage to cause a single serious injury to any Israeli civilian in any Israeli city—except, ironically, a Palestinian worker at an Israeli factory in Ashkelon.

They did not manage to drag Hamas into a full-scale war with Israel. They did not manage to hit a single target of any military value. Not a single demand of theirs was met, nor a single tactical goal they might have had over the course of three days of combat. By the time a cease fire went into effect Sunday night, they lost even more senior commanders, and used up much of their arsenal. Their rockets did manage to kill innocent civilians, but not innocent Israelis, innocent Palestinians in Gaza, mostly children.

The self-destructiveness of so much of the Palestinian cause often manifests as a macabre metaphor (the public celebrations that accompanied suicide bombings in the 1990s and 2000s spring to mind). Here there was not metaphor. Rockets whose only purpose was to murder innocent Israelis were either intercepted by Israeli technology or were falling on the unprotected homes of hapless Palestinians in Gaza. In the end, the jihadist wager was a multidimensional failure of tactics, planning, propaganda, and counterintelligence. PIJ aimed a 1974 hostage-taking, 1999 militia tactics, and 2008 rocket technology at a 2022 enemy.

Israel’s actions, meanwhile, show just how valuable self-criticism and self-correction can be. On every dimension, the performance of Israeli actors was at least slightly improved from previous rounds. The Iron Dome anti-missile system not only keeps up with new developments in Palestinian weapons, but its interception ratio keeps steadily rising, reaching 96 percent in this past week’s fighting. Israel’s efforts to avoid civilian casualties, already far in excess of what any other Western army does in similar operations, has also dramatically improved, especially since the first major Gaza war in 2008-9. Israel’s information campaign was proactive this time too, immediately providing dispositive evidence that PIJ rockets were responsible for the civilian deaths in Jabaliya before the festival of gory photos and phony investigations familiar from previous incidents could get underway.

Most importantly, Israel’s political leadership showed a kind of restraint and humility in its objectives and its management of domestic public opinion and expectations that previous governments had not. This has been a particularly acute problem for prime ministers from the center and left, who are wary of having any tactical restraint used against them politically by right-wing domestic opposition, especially in an election period. Shimon Peres in 1996 and Ehud Olmert in 2009, for instance, both made the same mistake of not knowing how to wrap up an operation quickly, got dragged deeper into unachievable goals, and saw their more moderate coalitions go down to defeat weeks later.

Lapid and Gantz outperformed them, and outperformed the right-wing leaders facing similar challenges in the past decade too. They set realistic goals for the operation rather than monopolizing the airwaves with grandiloquent pronouncements that would come back to haunt them. They took no steps to alienate Western allies or moderate Arab regimes that stood on the sidelines. And they knew when to stop.

Not all mistakes are doomed to be repeated in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Well, at least not all Israeli mistakes.

More about: Gaza, Israel & Zionism, Palestinian Islamic Jihad