Soon after October 7, 2023, as soldiers began mustering for the coming battles in Gaza, a remarkable phenomenon emerged almost spontaneously in military encampments around the country: pop-up barbecue stations serving soldiers gratis, run entirely by volunteers. The anthropologist Nir Avieli visited one such mangal (the Hebrew word, of Ottoman Turkish origin, for barbecue) and described what he witnessed.

At the Gilat intersection, right at the entrance to Route 242, one of the main arteries of the war, within a few days a huge cooking and logistics complex was established, which included awnings over synthetic grass carpeting in an area of about half a dunam [roughly 5,000 square feet], in which stalls served the soldiers food, mainly hamburgers grilled on the fire and hot dogs in buns. Next to the roast-meat stands, a stand was set up where homemade cakes were served, another stand with a sophisticated espresso machine that offered all the options you can get in a fashionable cafe in the center of the country, and various pop-up stands, such as a stand where a farmer squeezed juice from pomegranates he brought from his orchard. There was also a barbershop where volunteers gave haircuts to the soldiers, and a synagogue.

Next to the enclosure, huge mangalim many meters long were set up, on which many volunteers from all over the country grilled about 15,000 hamburgers every day, some of which were served to the soldiers on the spot, and some of which were sent to the soldiers at the front. The barbecues raised a cloud of heavy smoke and a strong aroma of grilled meat that everyone who passed by, day or night, saw and smelled.

Noa Asculai, sociology student at Ben-Gurion University recently called up the reserves, documented what it was like to be on the receiving end. She described a “processes of building a kind of alternative family, a company of male and female reserve soldiers that formed while dealing with brokenness and pain,” through sharing of food:

Like a family gathering for dinner, the members of the company gathered, excited and curious, around the food deliveries that were donated every day. A veteran reservist went around the tents and called everyone to come to the table while the rasapim [sergeant-majors] and the soldiers spread out the food and plates. When the signal was given, the plates were filled, the hunger disappeared, and an atmosphere of contentment after a good meal prevailed in the company.

This ersatz family didn’t wasn’t limited to the reservists, but also extended to the donors. To thank them, soldiers began sending pictures of themselves enjoying their meals. Women who worked to prepare the dishes began to be called “grandmothers,” emphasizing the sense of Israeli society as an extended family, where those serving in the IDF are the children. By providing the food, Asculai writes, these civilians fulfil their “yearning to take part in the war” by “filling the lives of the soldiers with flavor.”

The new developments on the battlefront may tell us something quite profound—not merely about the nature of this particular moment, but about the entire Israeli experience, something which religious thinkers and philosophers have struggled to capture since the very beginnings of the Jewish state. To understand why, we need to take a look at the annual holiday celebrated just last week and known informally as yom ha-mangal, the day of the barbecue—that is, Israeli independence day, Yom Ha-Atsma’ut.

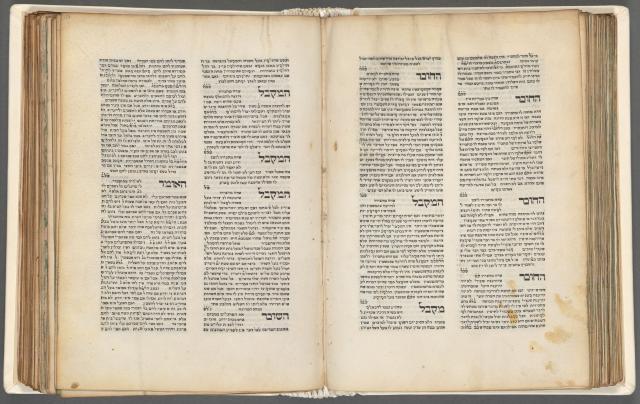

In March of 1949, one year after David Ben-Gurion’s declaration of the independence of the Jewish state on May 14, 1948, the fifth of Iyar was enshrined within Israeli law as a national holiday. In the months that followed, a synagogue service was crafted, which appeared in its final form less than a week before the holiday; it was mainly the work of Rabbis Moshe Zvi Neriah and Shaul Yisraeli, authorized (after some deletions) by the Sephardi chief rabbi Ben-Zion Meir Hai Uziel. The rite, which incorporates elements from the Sabbath, Passover, Hanukkah, Rosh Hodesh, Rosh Hashanah, and Yom Kippur liturgies, was quickly exported to the diaspora as the new state of Israel promoted the religious observance of Yom Ha-Atsma’ut throughout the Jewish world.

In the early years of the state, the service met with some internal and external criticism as an unoriginal “mishmash” that didn’t convey any unique motif for the day. Some of the leading lights of the Religious Zionism camp, Rabbis Shlomo Goren and S.Z. Kahana, carried out novel rituals on Mount Zion in competition with the synagogue service. In time, these radical alternatives faded away while the more conventional, chief rabbinate-approve liturgy has become standard among the non-haredi religious communities in Israel. Nonetheless, there is a general feeling that the new rites, even if broadly accepted, lack the authenticity of the older holiday liturgies.

For the staunchly Zionist Modern Orthodox communities in the U.S., the acceptance of special Yom Ha-Atsma’ut practices has also been complicated. Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik, the leading thinker of the American non-haredi Orthodox community and the honorary president of the American branch of the religious-Zionist World Mizrachi, expressed his dissatisfaction with the liturgy as early as 1953. He was reportedly sharply critical after witnessing its performance at Yeshiva University on May 11, 1978. In his conservative view, diametrically opposed to that of Rabbis Goren and Kahana, ritual innovation was certainly not called for. And even if it were, he deemed the hodgepodge liturgy was an “acute” failure, which combined sanctioned pre-existing elements that without any coherent halakhic (Jewish legal) framework. Such a synthetic service was too much for a rigorous halakhist like Soloveitchik.

The eclecticism of the service points to a more profound question about the meaning of the holiday. From 1948 to the present, the significance of the founding of Israeli statehood remains an unresolved question for Jewish theologians. Is it the dawning of a new epoch, and thus a spiritual challenge calling for repentance, anticipating the eschatological “Great Day of the Lord” prophesied in Malachi 3:23? A salvation from exile equivalent to the Exodus from Egypt? If so, perhaps it should derive its liturgy from that of such biblical holidays as Rosh Hashanah, Passover, or Shavuot. Or is it an event akin to the restoration of Jewish sovereignty following the revolt against the Seleucid Greeks, or the salvation from extermination described in the book of Esther? If so, the clear liturgical precedents are the festivals of Hanukkah and Purim, or the numerous local mini-Purims instituted by various Jewish communities over the centuries. Or perhaps Yom Ha-Atsma’ut, the commemoration of a secular political and military victory, falls into the most minor category of holiday, where mournful and supplicatory prayers are omitted, but no additional prayers are recited? What has instead emerged is a combination of all of these possibilities in a way that captures the underlying uncertainty, but also creates a rite that seems artificial and improvised.

In cases where rabbis are unable to determine the correct practice with appropriate certainty, both the Jerusalem and Babylonian Talmuds offer a straightforward solution: “go out and see what the community does and act accordingly.” That is, the rabbis should consult the organic practice of the community rather than the sterile intellectual exercises of its scholars. In this case, the one custom which has become almost universal on Yom Ha-Atsma’ut since the mid-1980s is the charcoal grilling of meat. This family-based practice has replaced the public gatherings and military marches that characterized Yom Ha-Atsma’ut celebrations in the early days of the state.

The obvious analogue here is to American July 4 celebrations, but more relevant are the ways these celebrations reflect upon characteristic aspects of the Israeli experience, drawing on secular traditions as well as religious practices, including some from the diaspora. As Avieli has observed, sharing food outdoors, sitting in a circle, and eating with one’s hands are all practices the mangal has in common with the meals eaten by Zionist scouting groups and the Palmach (the Haganah’s elite striking force), which played such important roles in the pre-statehood era. Moreover, the outdoor grilling of meat over charcoal flames is also a traditional activity for certain holidays—mostly commemorations of the deaths of saints—celebrated by Middle Eastern Jews: Lag ba-Omer, the Moroccan Mimouna, and the feast for the 20th-century sage Israel Abuhatzeira (Baba Sali). To varying degrees, these celebrations, complete with barbecues, have very much become part of the broader Israeli religious culture.

Avieli further observes that the process of packing up barbecue equipment, finding a good outdoor spot, and so forth has much in common with Israeli backpacking culture as well as with activities performed in army service. In short, for Israelis both religious (but not haredi) and secular, the key ritual of celebrating their country’s birth doesn’t involve prayer or ceremony, but a quintessentially Israeli activity that nonetheless draws on the precedent of holidays like Lag ba-Omer and Mimouna. This ritual doesn’t take place in the confines of the home (like the Passover seder) or in the communal space of the synagogue; rather it is performed by the family unit in a public park, surrounded by other family units.

It is not surprising, then, that a number of Religious Zionists have imbued the mangal with more profound religious meaning, often comparing it to the Temple sacrifices. Religious Zionists, in interviews with Avieli and other anthropologists, also frequently bring up a much more mundane aspect of the holiday: it is the one day in which it is possible to enjoy a family feast free of the prohibitions on driving and numerous other activities (as well as of long synagogue services) that characterize major Jewish holidays. These two responses—one that sees the holiday as a daring reenactment of biblical sacrifices, the other that shows appreciation for the fact that it resembles a secular holiday—share in common an assessment that Yom Ha-Atsma’ut is a unique festival, not one that can be easily fit into some preexisting mold, or patched together from other traditions.

At the same time, these conflicting approaches reflect some of the underlying ideological tensions within Religious Zionism. Are religious Jews supposed to accept the secular state and its civic culture as religious Jews who appreciate it as Jewishly significant, or are they to see it as a revolutionary, messianic transformation of Judaism? This question has a long and complex history, but it’s worth noting here that the former approach can appeal to Haredim and mainstream American Orthodoxy, which revere continuity and tradition, while the latter only has cachet among Israeli Religious Zionists.

In this light, the characterization of the Yom Ha-Atsma’ut meal as a biblical sacrifice makes good sense in the logic of Religious Zionism, but little or no sense within other forms of Orthodoxy, no matter how committed to Zionism. For the latter, sacrificial meals are wholly relegated to the messianic future, and reenactments bear more than a whiff of insult to the Temple’s sanctity.

With this in mind, let’s return to the present moment of crisis. Hamas’s attack on the Jewish communities of the Gaza envelope evoked comparisons not to prior terror attacks but to the Holocaust, generally seen as the antithesis of what the state of Israel represents. It evoked other things as well. On October 28th, Prime Minister Netanyahu delivered a public address in which he declared:

The war inside the Gaza Strip will be long and difficult—and we are ready for it. This [is] our second war of independence. We will fight to defend our homeland. We will fight and not retreat. We will fight on land, at sea and in the air. We will destroy the enemy above ground and below ground. We will fight and we will win.

If October 7 was akin to the Holocaust, and the war that followed it akin to the 1948 War of Independence, then, in a matter of two days, Israel relived the events encapsulated in the yearly eight-day sequence of Yom ha-Sho’ah, Yom ha-Zikaron (memorial day), and Yom Ha-Atsma’ut, a sequence consciously designed to encapsulate the story of the Jewish national near-death and rebirth in the 20th century.

The international phase of the 1948 War of Independence, milhemet Ha-Atsma’ut, came with the invasion of Israel’s Arab neighbor states immediately after Israel’s declaration of independence on May 14. Like the current war, it involved direct attacks on Israeli civilians and a sense of existential struggle for the country’s existence. The now commonplace comparison of the new war to the first one was matched nearly immediately by the extension of the key ritual of the latter’s commemoration, the mangal, to soldiers at bases and outposts, en masse.

Micah Goodman, an Israeli public intellectual, suggests that the face-to-face encounters over time—evident in the communities born of reserves duty—offer the potential for national reconciliation, so necessary after the polarizing, social-media-fed fights surrounding judicial reform in the nine months prior to the Hamas assault.

In 2023, a new and updated model of community was created in Israel: the reserve companies. These communities are not a model of socialist ideology, like the kibbutzim, nor of capitalist ideology, like the high-techists. These are exemplary communities that demonstrate the possibility of transcending ideologies.

When we admire, we change. A society that admires rich people is a society that tends to be materialistic; a society that admires athletes is probably a sporty society; a society that admires intellectuals is probably a society with a high level of literacy; a society that admires generals is probably a society with militaristic tendencies. The object of our admiration changes us. Something of its qualities enters into us. What does a society look like that looks at the reserve companies with wonder and admiration? When we admire the sacrifice of the reservists, we also breathe in something of their unity and cohesion. The new model communities are an unplanned byproduct of the war. These are communities made up of thousands of reserve men and women, who left their homes to fight Israel’s enemies, and in practice bring peace to Israel.

Thus, in Goodman’s view, the war unites Israelis with each other at the battlefront, and can help ease civic strife.

Another strand in the anthropological data collected by Avieli is not merely reconciliation among members of different sociopolitical groups (often called “sectors” or “tribes”), but also a coming together across generational divides: between the elders, veterans of previous wars who now remain at home, and their children and grandchildren, whom they are sending off to fight a new war. At the mangalim I described at the outset of this essay, the young soldiers and comparatively young reservists humbly receive food, and the tradition it represents, from their parents and grandparents, reaffirming the most basic of social bonds even as trust in the state and its institutions had been ruptured. The food reinforces the sense of parenting on the part of the donors, and for the soldiers, eating at the parents’ table, around the grandmother’s (metaphorical) pot.

Who are these donors? Not just Israelis. Lee-At Salomon, who organizes barbecues with a group of volunteers based out of the Neria yishuv called “Binyamin’s BBQ Brigade” (named for fallen soldier Binyamin Airley) describes who sponsors the materials:

Last week’s sponsors were a Reform shul in Los Angeles. Usually the sponsors are friends and family of the people who are involved in the barbecues who we’ve reached out to, but we’ve already gotten out and some people who don’t know us have also started donating, which is nice. Some people come to Israel and see our advertisements and want to sponsor full barbecues, and from the whole spectrum of people—we haven’t had non-Jews yet, everyone is Jewish, but from everyone, we have Reform, we have Conservative—mostly Orthodox, but that is because of the pool of people that are helping out in the barbecue. We are only now starting out for people to hear about us outside of that group. We have also hilonim [secular Israelis]; we have people from everywhere. A few American Haredim gave.

Other Israelis, and diaspora Jews, assume the position of parent as well. This dovetails with Avieli’s description above of how the soldiers have become “the children of all of us.”

The way in which the barbecues’ execution reflects parental care and generational continuity is actually compatible with the historical belongingness central to haredi self-conception and historiography. The Zionist and Religious Zionist rebellions against the diasporic past, having succeeded, had become the establishment, and four generations on, are now tradition. One rabbi-reservist, Eitan Kupietzky, suggested to me that, ideologically speaking, what separates at least the most religiously stringent Zionist soldiers on the battlefield (known as hardalim, a portmanteau of “haredi nationalist”) and the Haredim who eschew military service is no longer the ethos of rupture versus continuity, but rather ossified, if not downright anachronistic, labels like “Zionist” and “anti-Zionist.” If so, what seems to be incompatibility might be overcome by political will born of necessity and the usual processes of popular historical revisionism (or more charitably, reimagination).

Re-experiencing the founding national drama, and trauma, may just have opened a space for renegotiating the rituals of Yom Ha-Atsma’ut in a different key: not of rupture and isolation, but of continuity, reconciliation, and healing.

Will current events finally resolve the liturgical and ritual ambiguity that marks Yom Ha’Atzma’ut?

Which festival meal will the Yom Ha-Atsma’ut barbecue be? The raucous, festive Purim meal shared with good friends? The solemn, ritually elaborate Passover meal which focuses on the family? Or the communal meals that have now become de rigueur on Simhat Torah, a day that from now on will already always be bound with both national mourning and a new iteration of Israeli independence?

Will the national reconciliation last, once the war is over and the last hostages, reservists, and evacuees have returned home? Will religious Zionism find its center and reclaim the recent Jewish past that it purposefully forgot? Will the Haredim come to see that the “reign of the apostates” (as they sometimes call the state of Israel has become anything but) and make some sort of peace with the Israeli national story? Will secular Israelis make peace with the existence of Haredim as serving some necessary, even valuable, social function in the maintenance of culture? Will the Yom Ha-Atsma’ut mangal acquire a more profound meaning as a time of the meeting of social sectors and generations? Will it be recognized, in one way or another, as the central religious ritual of the day?

Earlier, I quoted Malachi’s eschatological vision of the “great and dreadful day of the Lord.” Perhaps it is worth citing the next verse, which states that the prophet Elijah “will turn the hearts of the parents to their children, and the hearts of the children to their parents.” Which manifestation of God in history will emerge? As Israelis say, Yamim yagidu—only time will tell.

More about: Israel & Zionism