Once a week for the next few months, Mosaic will be publishing brief excerpts of Leon R. Kass’s new book on Exodus, Founding God’s Nation. Curious about one of the foundational texts of the Jewish tradition? Read along with us. To see earlier excerpts, go here.

This week, Jewish communities all over the world begin their study of Exodus 6:2-9:35, a portion of the text known by its first significant Hebrew word, “Va’eira.” Moses and Aaron have returned to Egypt, and God’s deliverance of the Israelites is underway.

In chapter six of Founding God’s Nation, from which the following excerpt is drawn, Kass asks two major questions about political founding, “How do the Children of Israel, for now an oppressed multitude of slaves, become a free, self-governing people? And how does Moses, for now a stranger in a strange land, come to be their leader and founder? Both transformations require contact with and separation from Egypt, the world’s premier civilization.” In this week’s selection, we bring you Kass’s summary of the Egyptian way of life.

What Is Egypt?

Egypt is not only the matrix out of which Israel emerges. It is also the human alternative against which Israel will be defined. Because Israel is to be the anti-Egypt, it is important to discover what Egypt is: its worldview, its politics, its way of knowing, its gods. The narrative of the plagues offers us wonderful material for considering these questions, though their secrets are difficult to extract. In a few cases, we are not sure what the plague really is; in each case, if we knew more about its explicit target, we could learn a lot more. To better prepare ourselves for learning about Egypt from the plagues, we should first collect things readers already know about biblical Egypt from Genesis and the first half-dozen chapters of Exodus, supplemented by a few additions from outside sources.

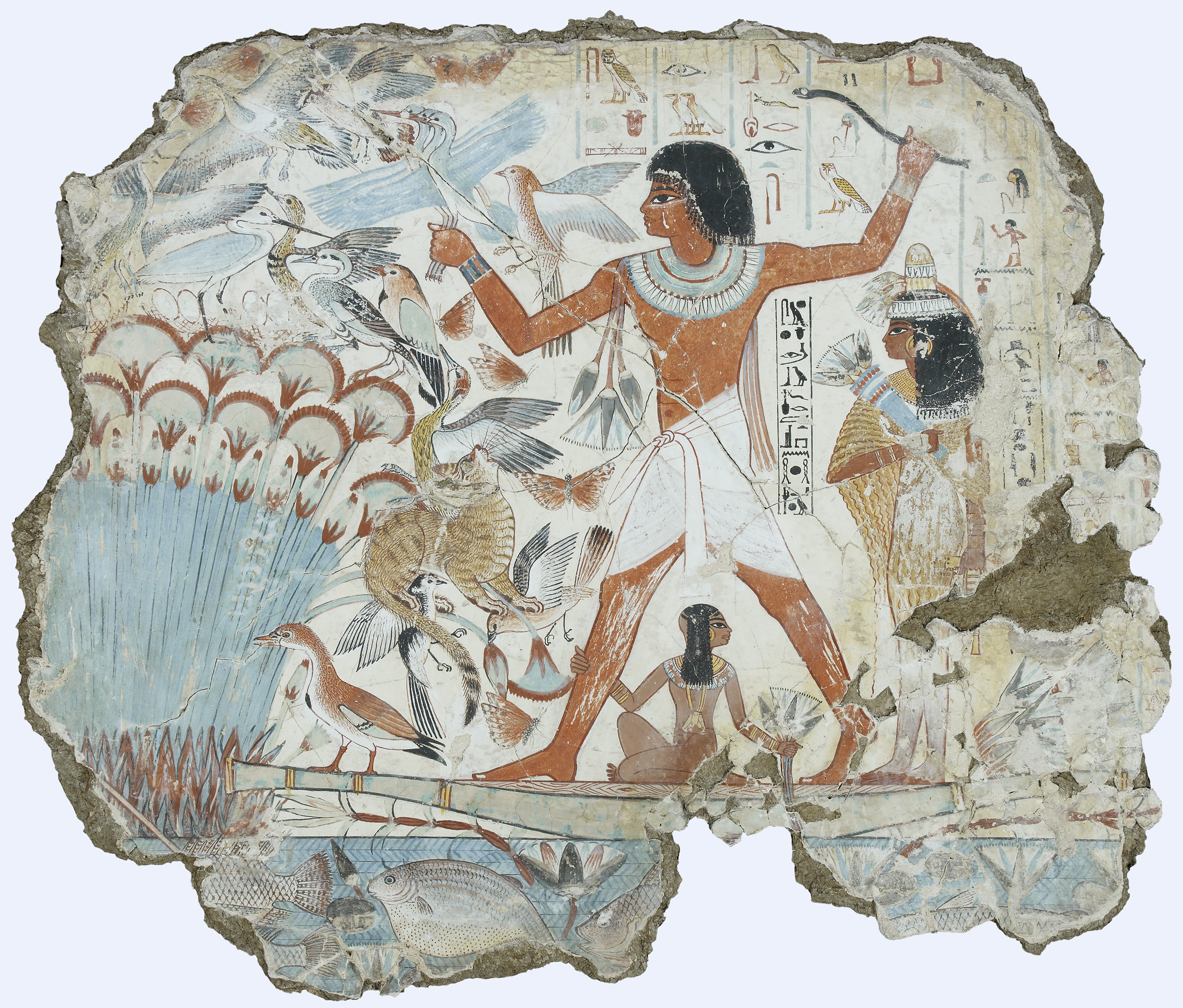

First, Egypt is the fertile land, the place of agricultural plenty, the place to which everyone turns when there is a famine. Its fertility is the gift not of heaven-sent rain but of the Nile, which seasonally floods the land, nourishing each year’s crop. Second, partly but not only for agricultural reasons, Egypt reveres the sun, which it treats as a god, Ra, the immortal and glorious source of light, warmth, and growth, indispensable to Egypt’s prosperity. Whereas the Nile is a parochial “deity,” all Egypt’s own, worship of the sun expresses Egypt’s opening to the universal. The mind of Egypt is hardly insular. Third, along with the regular movements of the Nile, the seasonal revolutions of the sun, absolutely reliable, create the impression that the powers of nature are, at least in part, friendly to human life. Nature is cyclical, dependable, eternal—and to that extent worthy of reverence. Fourth, and on the other hand, Egypt is obsessed with decay and death—two massive and most unwelcome natural facts. It is culturally preoccupied not with morality but mortality: with the natural goods of life, health, fertility, ageless bodily beauty, and, especially, longevity. We recall, from Genesis, Pharaoh’s impertinent question to Jacob on their first meeting, “How old are you?” meaning perhaps, “Are you older than me?” (Gen. 47:8–10). We recall also the Pyramids, tombs of the Pharaohs awaiting reanimation, and the Egyptian customs of embalming and mummification, practiced also on Jacob’s beloved son Joseph, as reported in the very last words of Genesis.

Fifth, we learn from extra-biblical sources that many natural beings are regarded in Egypt as emblems of natural powers or ideas and are revered as deities for their “support” of the blessings of life, fertility, and longevity. The frog, for example, is an emblem of fertility, and the frog-headed goddess Heket is revered for her influence on childbearing; the bull (Apis) is an emblem of masculine strength and potency; the cow is an emblem of birth and maternal nurture, and the cow-headed goddess Hathor is revered as the source of rebirth and rejuvenation; the scarab or dung beetle, thought to emerge spontaneously out of excrement, is an emblem of immortality. The number of such emblematic creatures is very large. They should not be confused with the anthropomorphic gods that Homer and Hesiod introduced into ancient Greece, gods that made the indifferent cosmos appear less alien to human life, interacted directly with particular human beings, and could be appealed to for personal assistance. The gods of Egypt are best seen as signs of natural powers crucial to human life and therefore worthy of awe and reverence.

Sixth, an important corollary of this Egyptian polytheism is the low cosmic standing of humankind and human affairs. Human beings have no special or exalted status in the cosmic whole. Egypt does not look beyond nature to any transcendent source, one that would be the intelligent cause and author of nature, one in relation to whom human beings would have special standing. Their cosmology includes nothing able to correct the silence of nature and nature gods about justice and other ethical goods important to human beings. Egypt is poles apart from the biblical teaching that the human being is the most godlike (tselem elohim) of the creatures, higher than all the others both on earth and in the heavens.

Seventh, partly but not only because of the problems of decay and death, change is altogether unwelcome to the Egyptian mentality. The men shave their bodies and heads to remove evidence of aging (as did Joseph when, summoned from prison, he first came to Pharaoh). Egyptian hieroglyphs or ideograms are static representations of changing things. Stasis or recurrent cyclical movement (changeless change), not progress in time, is the preferred idea in Egypt.

Eighth, and very important, the emphasis on picture writing and visible forms is connected with the epistemic preeminence of the sense of sight: seeing, for the Egyptians, is the royal road to knowledge, and seeing is believing. Pharaoh sees wonders but does not listen to their voice (or to the speech of Moses), and he forgets them when they disappear. In contrast, the Israelites will get their truths largely through hearing, through memory, and through stories.

Ninth is the preeminence of technology, which goes beyond the very visible pyramids and storage cities. Although the public religion in Egypt officially worships nature and natural beings, the “wise men” of Egypt—working secretly in Pharaoh’s palace—use their knowledge of nature to alter it. To make nature friendlier to human life, they develop “secret arts” (magic, sorcery) for controlling nature. As we will see from the deeds of the magicians we soon meet, they are especially interested in finding ways to convert the lifeless into the living and to reanimate the royal dead whom the palace physicians can only preserve from decay by embalming.

Finally, Egypt is politically an autocracy, presided over by one man who is regarded as a god and who rules according to his will and without external restraint. Egypt also boasts an elaborate and centralized administration (first introduced by Joseph, “father to Pharaoh”), which is itself another form of rational mastery over things. But Egypt lacks any real politics (rule addressed to the souls of men). Administration and technology, not law and governance, are supreme. Not incidentally, most native Egyptians are also indentured servants of Pharaoh—another of Joseph’s gifts to a previous Pharaoh. Given the absence of a worldview in which human beings have a special relation to the divine, it is not surprising that Egypt practices a politics in which one man can lord it over everyone else and other human beings count for little or nothing at all. As the contest with Pharaoh will make plain, his willful rule finally means accepting the destruction of the very people whose safety and well-being he presumably serves.

So what, then, is Egypt? We strongly suspect that the ten features we have just listed are not unconnected qualities. Rather, they appear to be interrelated aspects of a way of life that rests on a coherent worldview in which the cosmic powers appear to be hospitable but are finally indifferent to human life; in which human beings are orphans lacking special standing or purpose; and in which, finally, only man—only the strongest man—can be a god (that is, an awesome benefactor) to men. In subsequent passages, the Torah will sum up the meaning of Egypt in a single recurring epithet: the house of bondage (or “slavery”; beyt avadim)—a house that is not a home; a bondage that enslaves not only the body but also the mind, the heart, and the soul. Where people think that human life is unendowed and only a powerful man can be a god to men, slavery—the absence of freedom in all its forms—is the only logical outcome.

Against this background, we can see more clearly why the contest of the plagues is at once political, epistemological, psychological, and metaphysical-theological. It is not merely a strategic device for weakening Egypt and enhancing Moses’s standing so that he may better defeat Pharaoh and deliver the Children of Israel from bondage. It is not merely a punitive system meant to dispense justice for Egyptian wrongdoing. And it is not merely a power struggle between Pharaoh King of Egypt and the Lord God of Israel. It is also and especially a program of education. It is a contest of ideas and worldviews—about god, man, and nature; about rulers and ruled; and about knowing itself—that will reveal the truth of these matters to Moses and the Children of Israel, to the surrounding world, and perhaps most especially to readers of the text.

Excerpted and adapted from Founding God’s Nation: Reading Exodus by Leon R. Kass. Published by Yale University Press in January 2021. Reproduced by permission.

More about: Exodus, Hebrew Bible, Reading Exodus with Leon Kass, Religion & Holidays