I read Moshe Koppel’s recent essay on AI and Jewish thought with great interest. Koppel eloquently describes how Judaism’s solutions for the problems presented by AI will emerge and sets forth a theory about why this old religion is up to the task of navigating a world in the middle of a technological revolution. What I wish to do here is provide two critiques: one methodological, the other substantive.

The first is not specific to Koppel’s essay but applies to much that has been written on the subject. Since the launch of ChatGPT in November 2022, Jewish writing about artificial intelligence has been replete with initial reactions, but there has been little evidence that writers on the topic are engaging in constructive dialogue, let alone reading one another. This would be fine if the Jewish AI discourse was new, but it is almost as old as AI itself. Norman Lamm, a leading American rabbi, and Azriel Rosenfeld, an ordained rabbi and pioneering computer scientist, were writing about artificial life in the 1960s. Even leaving aside discussions of the golem—whose usefulness as an AI stand-in is debatable—by my count at least a dozen articles about Judaism and AI have been published in academic or halakhic journals since that time, not to mention many online articles and responsa. Collectively, this research has already uncovered many primary texts that may prove to be touchstones in the development of a “Jewish perspective” on AI. We’ve made significant progress, at least on paper.

But progress is worthless if it is ignored. Open questions, even great ones, do not make a field of study if nobody is attempting to answer them. Koppel champions Judaism’s tradition of dissent and refinement as a key to the Jewish response, but I have seen article after well-meaning article on the subject fail to elicit responses from rabbis, scholars, community leaders, or Jewish intellectuals. In this age of technological wonders, why do we insist on reinventing the wheel?

The answer, I suspect, mostly has to do with the debate’s nebulous stakes. As long as it remains unclear why anyone should care what Jews think about AI, Jews will not care what other Jews think about AI, either, except to the extent that they find the subject entertaining. The problem is that good questions are sometimes more satisfying than hard answers.

In fact, the stakes are quite high. AI is a world-shaking technology, and it is not at all clear that it is consistently being developed with human welfare in mind. As I wrote in December, Jewish thinkers have an opportunity to stake a moral claim in a global conversation. If we do not—if we continue simply asking good questions—our claim to being a moral force becomes less credible. We risk allowing our ethics to become obsolete.

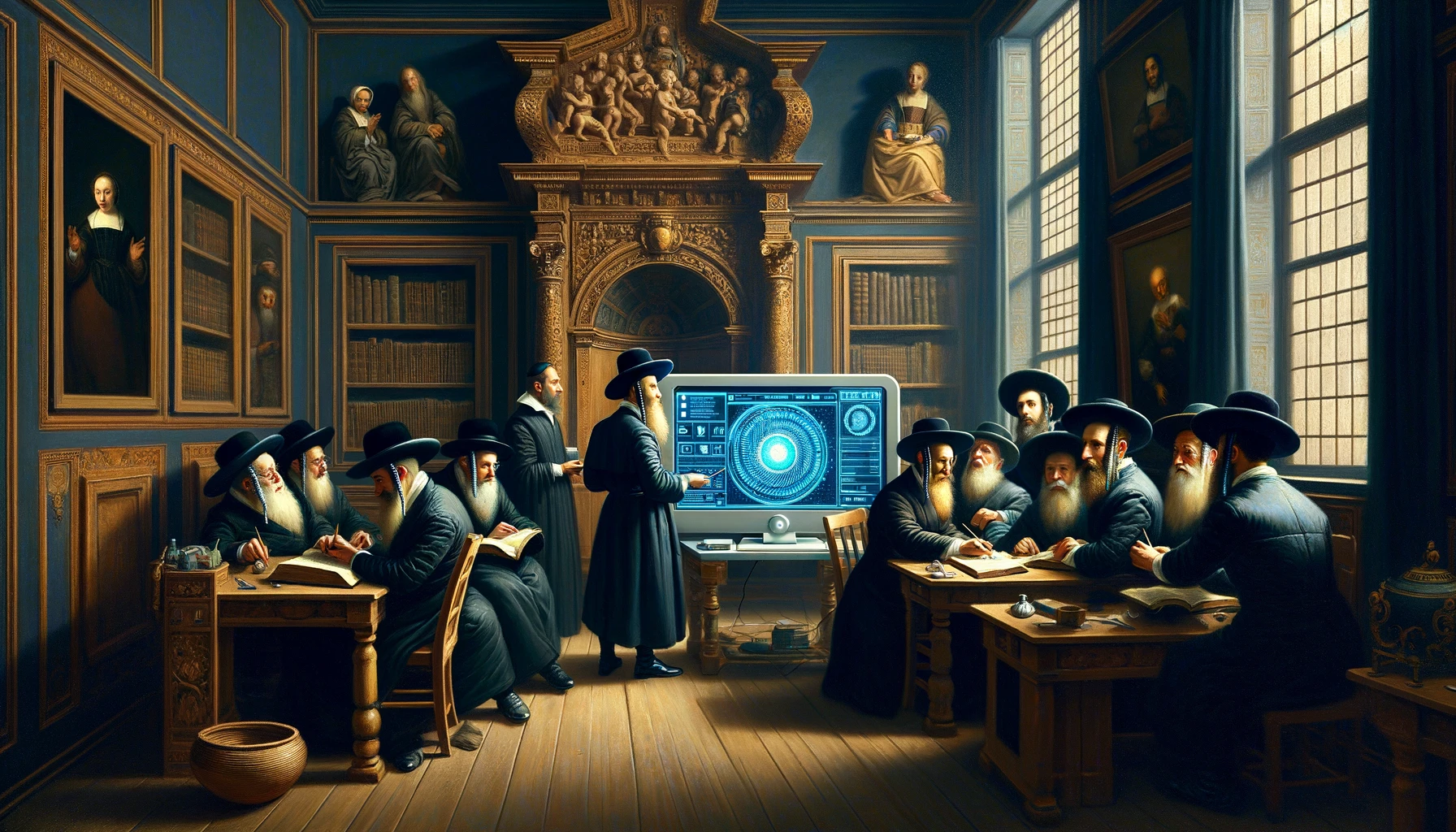

Koppel certainly wishes to see Jewish thought about AI develop, and in one respect he is doing much more than asking good questions. His Dicta project, which is now using this technology to increase processing speed dramatically for the analysis of religious texts, is a part of a long history of what I call “pious coding” that over the last 60 years has fully embraced cutting-edge computational techniques to revolutionize Torah study over and again. This history—which has been driven by an often implicit but widely-held desire to know Torah in all its beauty and to the greatest possible extent—deserves much praise. Today the pious coder should rightfully be placed alongside the scribe, shoḥet, and kosher baker as one of the key enablers of Jewish life.

But Koppel wishes to speak to life outside of Torah study, and here he is on shakier ground. He expresses confidence in the tried-and-true method of rabbis making considered judgments. He also suggests that (Orthodox) Jewish communities already house institutions that will partially inoculate them from AI’s effects: the beit midrash, which promotes something other than work to fill one’s day; and Shabbat, which has proceeded cautiously when new technologies threatened to disrupt the cherished feel of the day.

I agree, up to a point. Koppel correctly highlights the layer of activity in which a Jewish response is most likely to be effective. At present, tech regulation typically happens on either the personal level, the corporate level, or the governmental level. Personal regulation (e.g., limiting screen time) is very hard, especially when it interferes with social or professional life. Corporate regulation is difficult because it often requires companies to work against financial interest, and governmental regulation is often slow and skewed by partisan concerns. To the degree that Jewish institutions and communities can set their own rules, they can act quickly to combat the social and economic pressures that make personal regulation difficult, and even act as models for other communities (and even countries) to emulate.

But, as Chaim Saiman has already noted in his response, halakhic engagement with new technologies does not always orbit around a moral center; in fact, sophisticated legal responses can end up obscuring foundational moral principles just as easily as they can exemplify them. As Saiman argues, and I have documented elsewhere, the stark differences between the development of Shabbat and kosher regulation over the last century is likely due to the fact that Shabbat is understood to have a clear societal and even theological value, while kashrut lacks any such agreed-upon purpose. Rather than assuming that Jewish communities already have a north star when it comes to AI (they don’t), the top priority for Jewish leaders must be formulating basic moral attitudes from which particular rules can eventually be derived. This is a task more in the realm of aggadah, of parable and moral investigation, than of halakhah. Questions about self-driving cars must take a backseat to the more fundamental questions—and answers—about the theological implications of bringing into the world something created in our own image.

To my mind, the most important question on this front is determining the correct relationship between AI and humanity. The notion of AI as a type of god, which one today hears sometimes from the technology’s secular boosters, is both dangerous and literally idolatrous; it elevates a human creation in a way that allows developers to avoid liability while suggesting that we place trust in opaque algorithms. This sentiment must be forcefully repudiated. Instead, it is far more appropriate to treat AI as a kind of child: one that is growing in power and resembles its “parents” but mimics them to a fault. This idea, which can easily be connected to Judaism’s vast stores of wisdom on parent-child relationships (and even descriptions of humanity as God’s children) sets forth a path that emphasizes our long-term duty of care.

It is also a time to activate conversations within and among Jewish communities. Good leaders act in response to the desires of their constituents. Yet it is far from clear what Jewish communities actually want from AI. As Koppel writes regarding the dangers of utilitarian thinking, “the whole process depends much more on the hard problem of figuring out what you want to maximize than on the technical problem of how to maximize it.” What is true about AI is true about us as well.

One of the reasons that halakhah seems like a promising tool with which to respond to AI is that it provides clear responses: forbidden or permitted, fulfilling obligations or not fulfilling them, etc. Yet some of the most important challenges AI will raise lie outside of the realm of halakhah, and it is precisely in responding to these challenges that Judaism’s repository of wisdom is most badly needed. Consider, for instance, that the most consequential decisions regarding AI will be made not by individual users but by governments, large corporations, or singularly powerful individuals like Elon Musk. These are not the sort of people typically requesting rabbinic guidance.

The result of this mismatch, I worry, is that rabbinic responses to AI may excessively focus on the issues where individuals and Jewish communities do have agency and ignore the evolving systems which bestowed them with that agency. In the near future, rabbis may rule on whether it is acceptable to feed the writings of a deceased parent into an LLM so that one’s children can “speak” to a dead grandparent—but they are apt to ignore the question of whether such systems should exist commercially in the world in the first place. Given that AI systems are known to give bad actors unprecedented abusive power—witness the ease with which pornographic Taylor Swift deepfakes flooded the internet recently—I am concerned that this scale of response will fail to engage in the kinds of systemic critiques that are so badly needed. AI’s impact on society is due not just to its abilities, but to the fantastic speed at which it is being rolled out across human civilization. Responding only with regard to individual activity is simply inadequate. And it’s not too much to ask for Jewish leaders to try to formulate some answers to these moral questions in language other than that of halakhah, with the hope of having some positive influence on the wider world.

We cannot respond to these challenges unless we are honest with ourselves about the places where our tradition is inadequate. Jews are stewards of an ancient, living tradition of ethical knowledge. To some, this body of knowledge already contains a secret sauce—perfect principles, a culture of argumentation and self-refinement, whatever you imagine—and as a result there is no invention or circumstance that could leave it dumbfounded, at a loss for answers. Koppel seems to argue in this direction, claiming that the tradition can stand its ground against any newcomer: we’ve done it before and we’ll do it again; trust the process.

I agree with the premise, but not the conclusion. The antiquity and durability of the Jewish ethical code is testament not to the perfection of its initial conditions, but rather to the dogged determination of generations of leaders to maintain its relevance against threats of violence and a world in constant flux. If the Torah is a rich inheritance, then we must not be that nth-generation trust-fund child who knows only how to spend it down. We dare not be confident. As Benjamin Franklin might have said: Judaism is a living tradition—if we can keep it.

More about: AI, Artificial intelligence, Halakhah, Politics & Current Affairs, Religion & Holidays