Got a question for Philologos? Ask him yourself at [email protected].

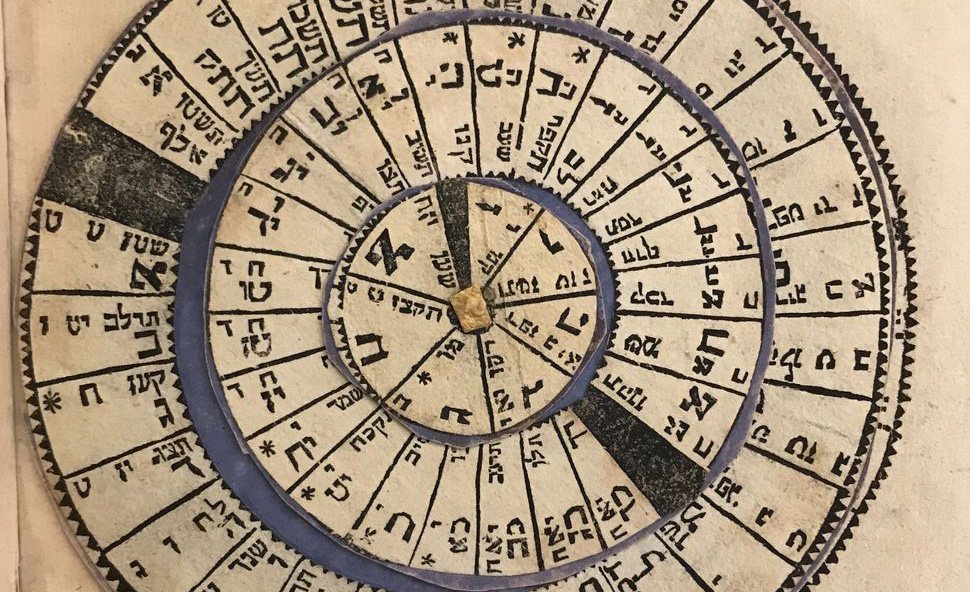

As observed in our previous column, when the seven-day week was widely adopted in the Roman empire in the early centuries of the Common Era, there were two competing ways of naming its days. One was the pagan way of associating these days with the sun, moon, and five visible planets Mars, Mercury, Jupiter, Venus, and Saturn. The other was the Jewish way of numbering them.

It is difficult to say, historically, how much Jews and Judaism had to do with the early stages of the seven-day week’s spread. They certainly influenced it to some extent. By the 1st century CE, there was a Jewish presence in almost all parts of the Graeco-Roman world, and judging from the many references to them by Latin and Greek writers, the Jewish week and its Sabbath were well-known to non-Jews, as was the Sabbath’s association in their minds with the planet Saturn. In a fanciful account of the Jews’ origins in the exodus from Egypt, during which they supposedly found water after seven days of thirsting in the desert, the Roman historian Tacitus (56–120 CE) wrote:

They are said to have devoted the seventh day to rest, because that day brought an end to their troubles. . . . Others maintain that they do this in honor of Saturn, either because their religious principles are derived from the Idaei, [a Cretan people from which iudaeus, “Jew,” was believed to derive], who are said to have been driven out [of Crete] with Saturn [i.e., when Saturn or Kronos, according to Greek mythology, was deposed as head of the Greek pantheon by Jupiter or Zeus], and to have become the ancestors of the Jewish people; or else because of the seven heavenly bodies that govern the lives of men, the planet Saturn moves in the topmost orbit and exercises a peculiar influence.

But it was Christianity, which took the seven-day week from Judaism while moving its day of rest from Saturday to Sunday, that was responsible for its being declared an official Roman institution by the emperor Constantine in 321 CE. (A year later he established Christianity as the empire’s official religion.) It was Constantine, too, who moved the empire’s capital from Rome to the new city of Constantinople in Asia Minor that bore his name, thereby paving the way for a split between the western, Latin-speaking half of the empire and its eastern, Greek-speaking half, and for an eventual schism between the Roman Catholic and Greek Orthodox churches.

This schism affected the naming of days, too. Both churches retained Saturday as the week’s last day while renaming Sunday, the day of Jesus’s supposed resurrection, “the Lord’s Day” (Latin Dies Dominica, later shortened to Dominica, and Greek Kyriake Himera or Kyriake.) Yet the church in the West made its peace with the old planetary names for the week’s other days, whereas in the East it rejected them as remnants of paganism and adopted the Jewish system. The Greek Monday, formerly Selenes Himera, “the Day of the Moon,” became Devtera Himera or “Second Day,” subsequently abbreviated to Devtera, while Tuesday was renamed Triti, “Third”; Wednesday, Tetari, “Fourth”; and Thursday Pempti, “Fifth.” Apart from Sunday, Saturday alone was given a non-numerical name: Sabbaton, the Hebrew Shabbat.

An even more striking inheritance from Judaism was the Greek church’s name for Friday. This was not Ektos, “Sixth,” but Paraskeve, literally, “Preparation”—a noun derived from the Greek verb paraskevadzo, to prepare or get ready. As is made clear by two passages in the Greek New Testament, the allusion is to preparing for Shabbat. Thus, in the gospel of Mark we read that, on the Friday of Jesus’ crucifixion, which was “the day of Preparation [ho paraskeve], that is, the day before the Sabbath [prosabbaton], Joseph of Arimethea . . . went boldly to [Pontius] Pilate and asked for the body of Jesus.” The Greek pronoun pro, when referring to events taking place in time, means “before,” and prosabbaton is an obvious translation of Hebrew erev Shabbat, the eve of, or day before, the Sabbath—a customary Jewish way of referring to what in the biblical account of Creation (and in contemporary Israeli Hebrew) is called Yom Shishi, “Sixth Day.”

Paraskeve is most likely a usage going back to Christianity’s earliest days, when its still Jewish followers observed Shabbat and spent Friday preparing for it. Apart from a number of Caucasian languages, such as Georgian and Chechen, this usage was not passed on to other followers of the Greek Orthodox rite, such as the Armenians and the Slavs. Yet all Slavic languages, while counting Monday rather than Sunday as the start of the week, number at least some of its days. In Russian, for example, Sunday is voskresyenye, “[the Day of] Resurrection,” and Monday, ponyedyelnik, “the Day after [the Day of] No Work,” after which Tuesday is vtornik, “Second”; Wednesday, sreda, “Middle [of the week]”; Thursday, chetverg, “Fourth,”; and Friday, pyatnitsa, “Fifth,” while Saturday is subbota.

A smattering of other peoples who embraced Roman Catholicism chose this path, too, especially in the Baltic region, where the Slavic influence was strong. (Lithuanian, indeed, may be the only European language in which all seven of the week’s days go by numbers.) Portuguese, too, has some numbered days; these came from the Arabic spoken in the Iberian Peninsula after the Muslim conquest, and were taken by Islam from Judaism. Yet in all the other Romance languages, the old planetary names remained in place. Sunday, Latin Domenica, unchanged in Italian, became Spanish domingo, French dimanche, and Romanian duminică; Monday, Dies Lunae, evolved into Italian lunedi, Spanish lunes, French lundi, and Romanian luni; Tuesday, Dies Martis, into martedi, martes, mardi, and marţi, and so on through Friday, Dies Veneris or the Day of Venus, which yielded venerdí, viernes, vendredi, and vineri. As in the East, however, Saturday was Christianized as sabato, sabado, samedi, and sȃmbătă.

In the Germanic languages, on the other hand, the Church lost the naming battle for all the days of the week, Saturday and Sunday included; moreover, the pagan names that prevailed were not those of the planets but those of Norse gods identified with the Roman gods whom the planets were named for. In old English, for example, Latin Dies Solis and Dies Lunae became Sun Day and Moon Day (Sonnandaeg and Monandaeg), whereas Dies Martis, the Day of Mars, was named Tiw’s Day for the parallel Norse god of war; Dies Mercurii was Woden’s Day; Dies Iovis, Thor’s Day; and Dies Veneris, Frigga’s Day, with Dies Saturnis remaining Saturn’s Day. The only Germanic language to number some of its days was Icelandic, which has þridjudagur, “Third Day,” for Tuesday and Fimmtudugur, “Fifth Day,” for Thursday. Europe’s fourth major linguistic group, the Celtic languages, stuck for the most part with the Roman gods, as in Welsh dydd Mawrth, for Dies Martis and dydd Gwener for Dies Veneris.

Once established in Europe and western Asia, the seven-day week continued to spread. Before the end of the Common Era’s first millennium, familiarity with it, if not its widespread practice, had reached India, China, and even Japan—and with it, the same rivalry between its Jewish numerical and European pagan-astronomical nomenclatures. In India, the latter was adopted, producing Hindi ravivaar or Sun Day, somvaar or Moon Day, mangalvaar or Mars Day, and so on through the other planets. The Chinese preferred numbers. Starting the week with Monday, they called it shingchiyi (xingqiyi in official transcription), “Week-One.” Tuesday was then “Week-Two,” Wednesday “Week-Three,” and on through Saturday, with a gesture to the heavens on Sunday, shingchi’er, “The Day of the Sun,” or shingchitian, “The Day of the Sky.”

So it has gone with nearly all of the world’s languages, since nearly all of the world now observes the seven-day week. In many languages, there is a mixture of the two systems; in some, the Roman planetary names have been replaced by the names of natural elements or other things. (Japanese, for instance, has nichiyoubi, Sun Day; getsuyoubi, Moon Day; kayoubi, Fire Day; suiyoubi, Water Day; mokuyoubi, Wood Day; kinyoubi, Gold Day; and doyoubi, Earth Day.) Basically, though, it still comes down, in all its variety, to numbers or not. It may have started with the Babylonians, but in the end it was monotheistic Israel and pagan Rome that gave the world its feast of weeks.

Got a question for Philologos? Ask him yourself at [email protected].

More about: History & Ideas, Language