Philologos

Philologos, the renowned Jewish-language columnist, appears twice a month in Mosaic. Questions for him may be sent to his email address by clicking here.

Why Are the Anti-Israel Chants So Dull?

Compared to the wit of the anti-Vietnam slogans of the late 60s, the anti-Israel chants of today are aggressively tedious. What does that say about the chanters?

Did the Ancient Sage Hillel Really Invent the Sandwich?

The truth of the tale of Hillel and the “Hillel sandwich.”

Were There Arab Jews, and Did They Speak Judeo-Arabic?

Jews in Arab lands spoke much the same Arabic as their neighbors. But the notion that they thought of themselves as Arab Jews, pushed now in some circles, is a historical absurdity.

The Purim Grogger's Name Comes from Spain

The holiday noisemaker bears a suspicious resemblance to the Spanish carraca.

Why Goats Show Up in So Many Idioms

Hebrew is full of goats these days, and English and French aren’t too far behind. Where’d they all come from?

Tit for Tat Is a Bad Way of Arguing about Gaza

Two or three thoughts on the “dehumanizing” discourse.

The Linguistically Challenged International Court of Justice

It is apparently too much to expect fifteen expert jurists to understand how human language is commonly used.

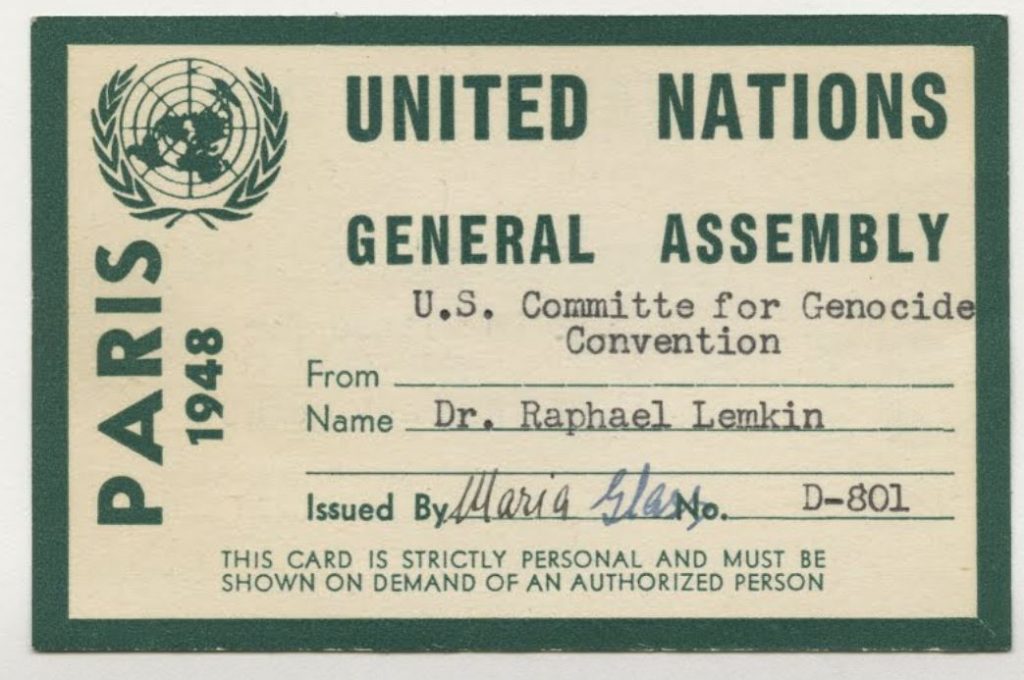

The Irony of "Genocide"

A Jewish lawyer coined the term because there was no word that described the murder of a whole people. But the definition he favored is so loose it can apply to almost any conflict.

The Secrets of the Jewish Leap Year

Some years in the Jewish calendar, like the current one, have an extra month. How’d that come about and why?

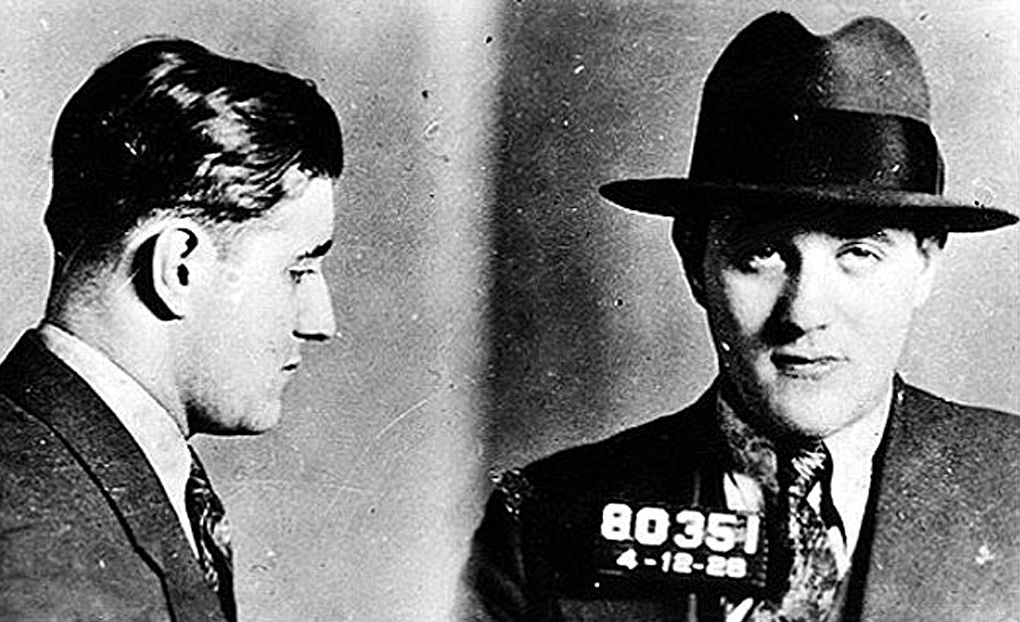

Does the Slang Word "Shamus" Come from the Yiddish "Shammash" or the Irish "Seamus"?

The long-running case of the word for private detective can finally be considered closed.

The Hebrew Language's Expression of the Year

Rarely heard in the speech of most Israelis in the past, b’sorot tovot, an ironic “good news,” has suddenly become a common way of saying goodbye.

What Invoking Amalek Means Today

The name of the biblical tribe of murderers, the arch-rivals of ancient Israel, has been much discussed in the wake of October 7. Is that appropriate?

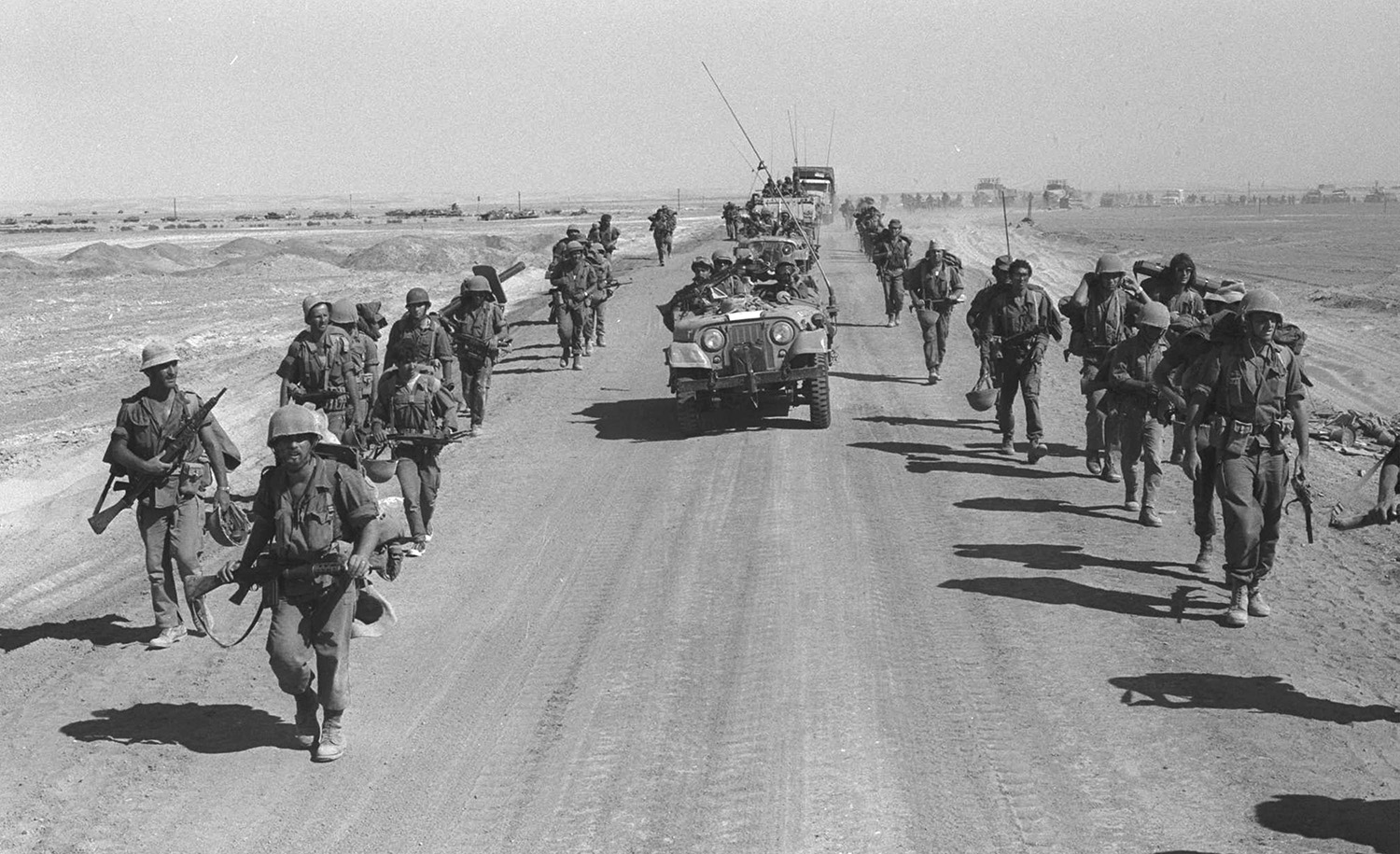

How Wars Get Their Names

Most wars, including the current one, are just called “the war” at first. The names that stick usually come years and sometimes centuries later.

Can the Hebrew Word for Catastrophic Blunder Be Translated?

A meḥdal occurred in 1973. It has now, in an eerily similar way, occurred again. What exactly does it mean in English?

The Mystery of the Angel of Rain

An ancient prayer for rain mentions an angel named Af-bri. But where did he come from?

"This Is the Yom Kippur of"

In the wake of the Yom Kippur War, the words yom kippur shel, “the Yom Kippur of,” have referred in Israeli speech to any debacle that might have been prevented by better judgment.

The Mysterious Glossary of Maimonides

What might the great scholar have been intending with a recently discovered list he made of seemingly random words from random European languages?

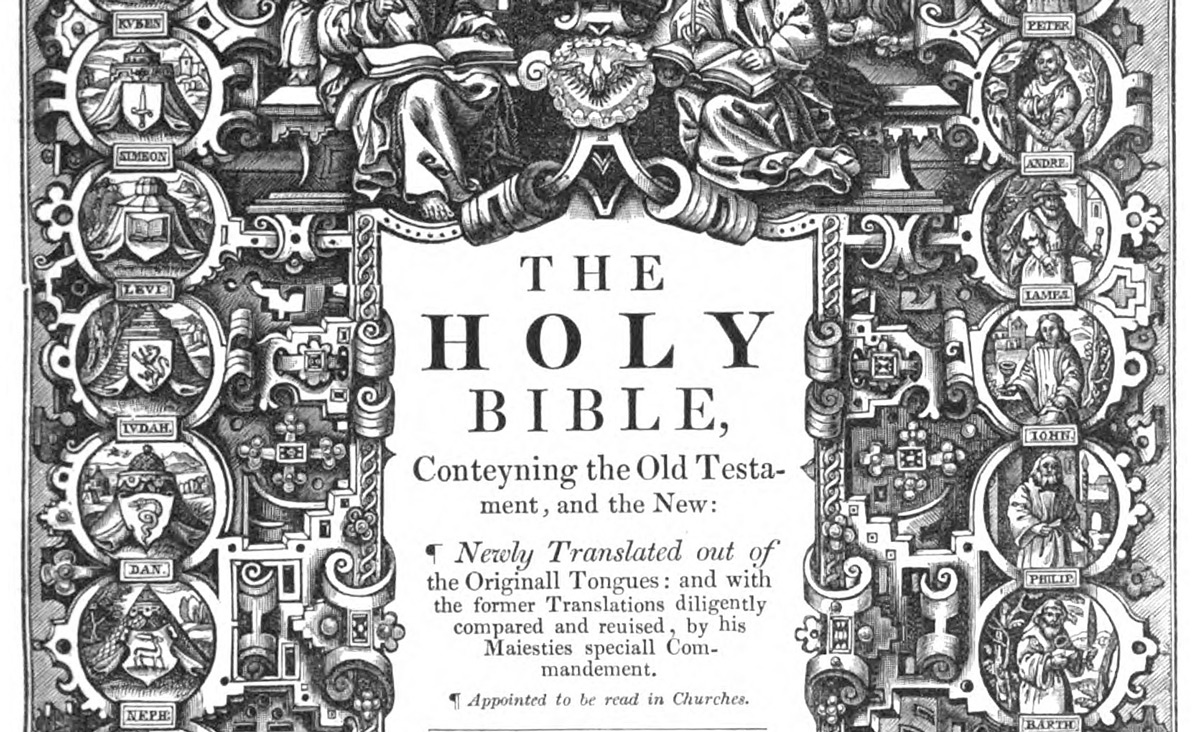

How the King James Bible Misled Generations of Readers

A misunderstanding about mirrors, with far-reaching, metaphysical consequences.

How Much Plato Did Paul or the Rabbis Know?

A reader’s question prompts Philologos to turn up a crucial link between the three.

Were the Rabbis Riffing on Corinthians?

Why is a phrase from a tractate in the Talmud so similar to one in Paul’s First Epistle to the Corinthians?

Just as the Siesta Disappears, Hebrew Finally Has Its Own Word For It

Will shnatz have arrived on the Hebrew scene just in time for it to denote something that no longer exists?

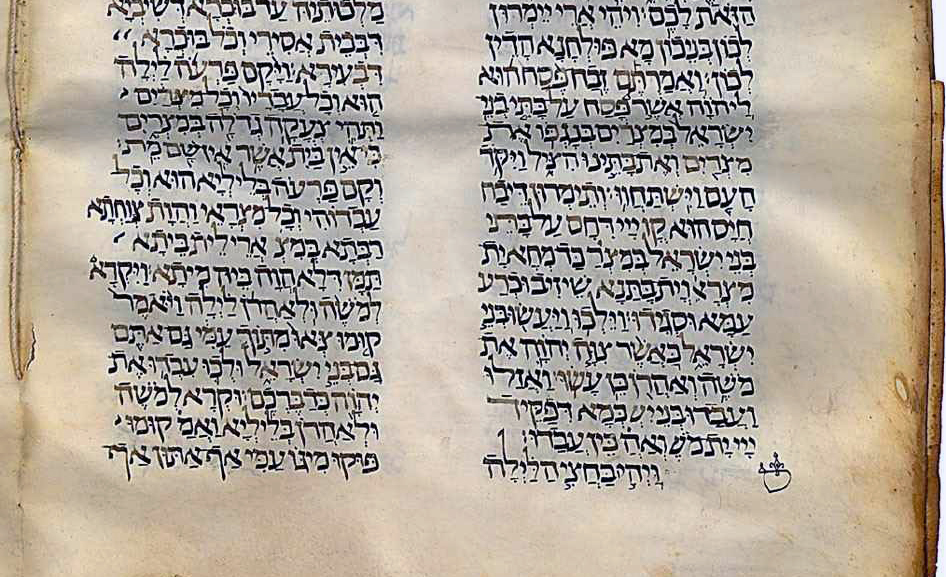

The Battle of the Seventy Translators

How many rabbis first translated the Hebrew Bible, and how many different translations did they produce?

The Wheels of Jewish Language in the New Netflix Show "Rough Diamonds"

One of the show’s main pleasures has to do with which of the four languages spoken by its main characters—Yiddish, Flemish, French, and English—they use with whom.

Is a Christian Delicacy Behind the Shlissel Challah Phenomenon?

Orthodox Jews on Instagram have become obsessed with baking key-shaped challah. Is the idea derived from a decidedly non-Orthodox source?

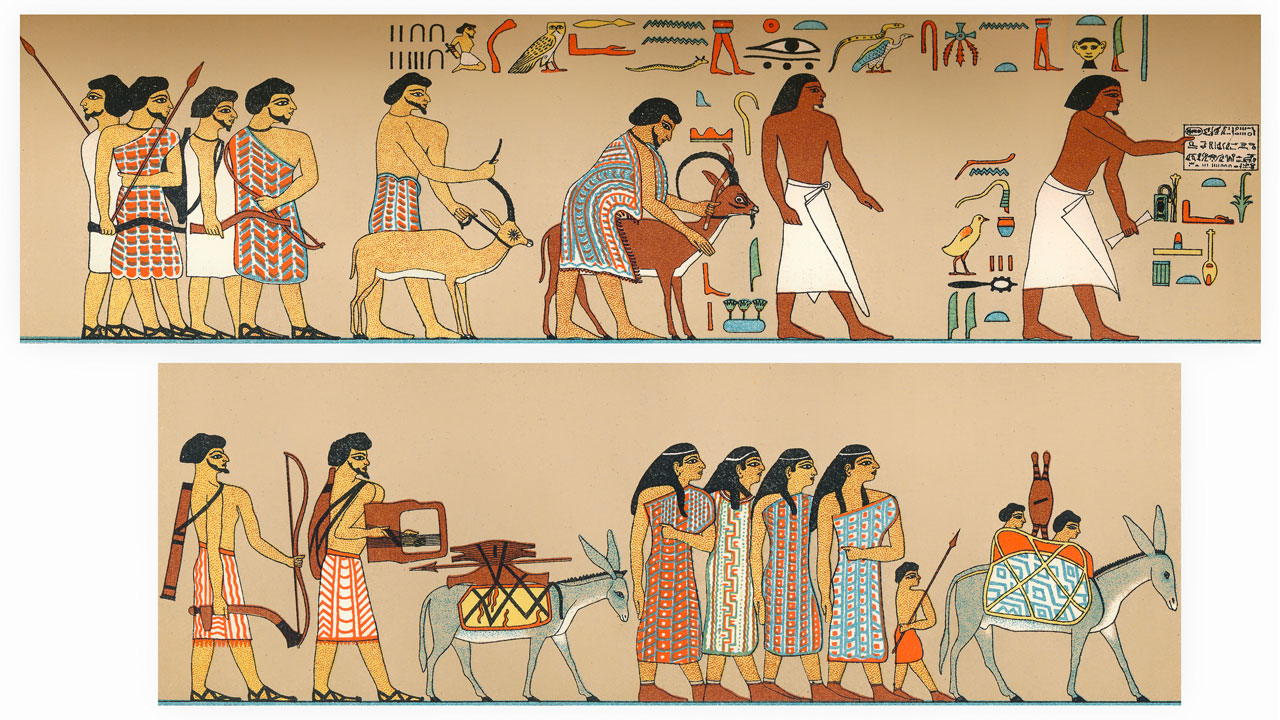

How Many Egyptian Words Made It into Biblical Hebrew?

And does their presence illuminate the book of Exodus—or is it simply a sign that ancient Egypt was a powerful nation?

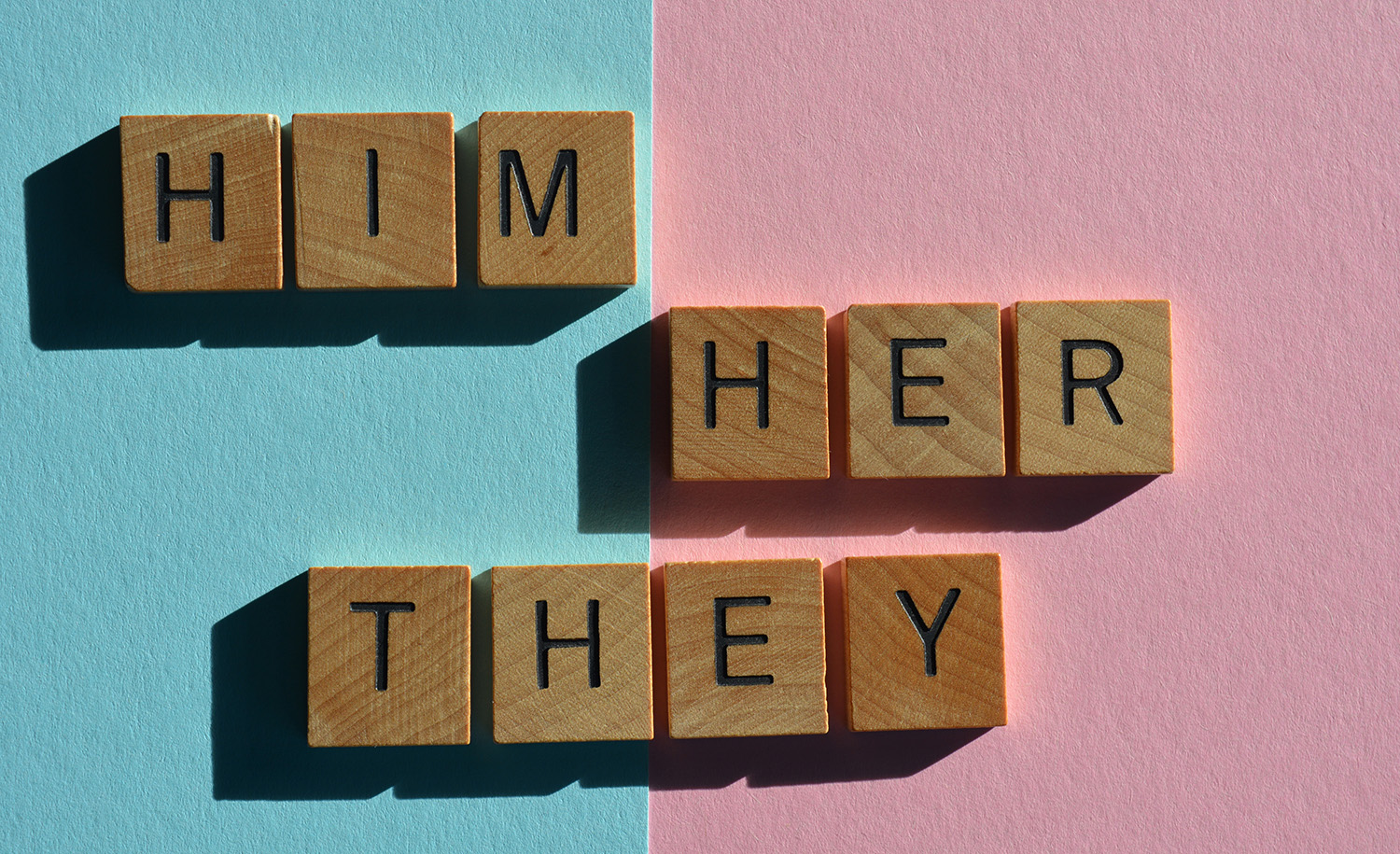

Monotheism and the Problem of God’s Pronouns

Will the Hebrew language allow us to call Him, Her?

Was Gutenberg's Printing Press Technology Stolen?

Stories circulated in Gutenberg’s lifetime of attempts to steal his invention while he was working on it. Can we know if they’re true?

"Female Citizens and Male Citizens of Israel!"

Where a new grammatical feature of Hebrew speech comes from.

Did Adam Speak Hebrew?

The ancient rabbis believed there was linguistic proof that the first man spoke Hebrew with God. Why?

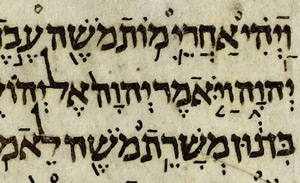

How Hebrew Came to Be Written From Right to Left

Hebrew was once written in both directions. How did it fix its direction, and what does that show about the history of writing in general?

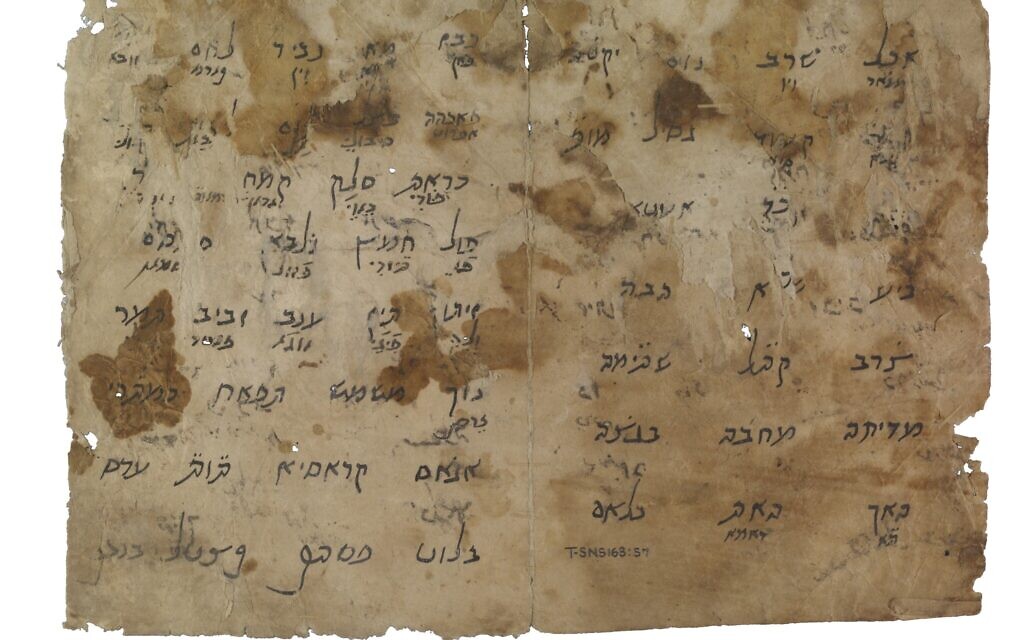

Is the Language Abraham Spoke Engraved on an Ancient Lice Comb?

For the first time, a whole sentence in ancient Canaanite has been found. Only six words long, it brings us many words closer to the age of the Patriarchs.

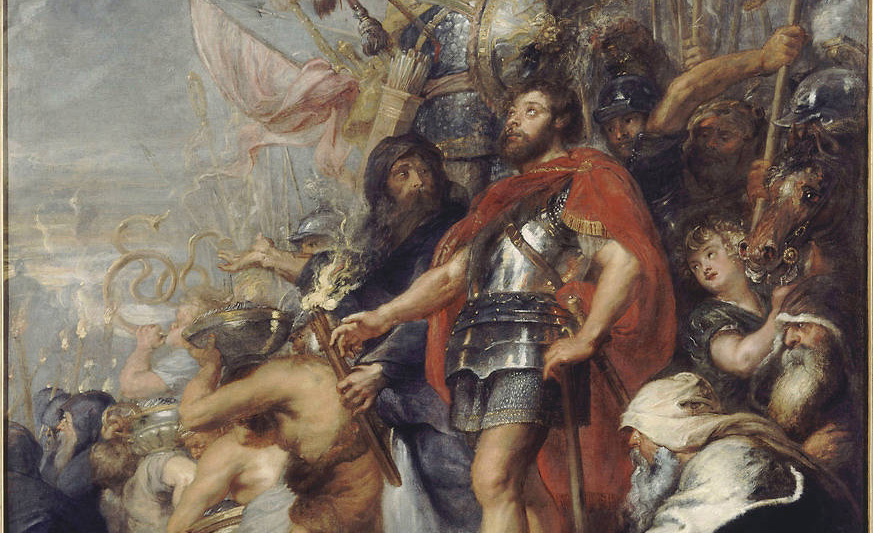

The Maccabees, the Greeks, and the Origins of the Conflict Between Hellenism and Hebraism

What the Maccabees called their enemies reveals much about how both cultures saw themselves and what the conflict between them meant for the world.

What Color Is Biblical Blue?

A hue like the sea, the sky, grass, and trees, available for $14.90 per gram at Amazon.

Did a 15th-Century Jew Beat Gutenberg to the Printing Press?

A newly released academic study hints as much.

Was There an Ancient Superlanguage Called Nostratic?

And could the story of the Tower of Babel actually reflect a dim folk-memory of its breakup?

The Scourge of "Jewsplaining"

I’ve been spared an encounter with the neologism until lately. But, frankly, now that I have made its acquaintance, I find it idiotic. (And don’t get me started about “goysplaining.”)

The Contradictions of Kol Nidrei

One renowned talmudic scholar called the now-beloved prayer a “foolish custom that is not to be followed.” What did he mean and how did it survive?

The Proof of the Exodus Hidden in the Ancient Word Sha’atnez

The word, like a small number of other Egyptian loanwords in the Bible, testifies to a period in which the early Israelite nation, or a part of it, was in intimate contact with Egyptian life.

Can Anyone Translate the Name of a New Israeli Political Party?

The Blue-and-White party has transformed into . . . well, it’s unclear, at least in English.

Is Yeshivish a New Jewish Language?

Some have claimed that the hybrid dialect is on its way to becoming a new Yiddish, as different from 21st-century English as Yiddish is from medieval German. Are they right?

Why Do Hebrew Speakers Pronounce the Same Word Multiple Ways?

The deultimization of the Hebrew language proceeds apace.

How Well Does My Computer Translate Hebrew?

In the end, one doesn’t know what to be struck by more: the fact that a computer can translate Hebrew at all, or the fact that when it does, it does so atrociously.

The History of Jews Giving Their Children Both Hebrew and English First Names

Jewish history has always known periods in which double naming existed, always in places in which Jews were relatively well-integrated in the non-Jewish society around them.

The Conceptual Poverty of "Crimes Against Humanity"

There is, unfortunately, nothing more human than most of the things called inhuman. That’s why in Jewish tradition “crimes against humanity” are thought of as crimes against divinity.

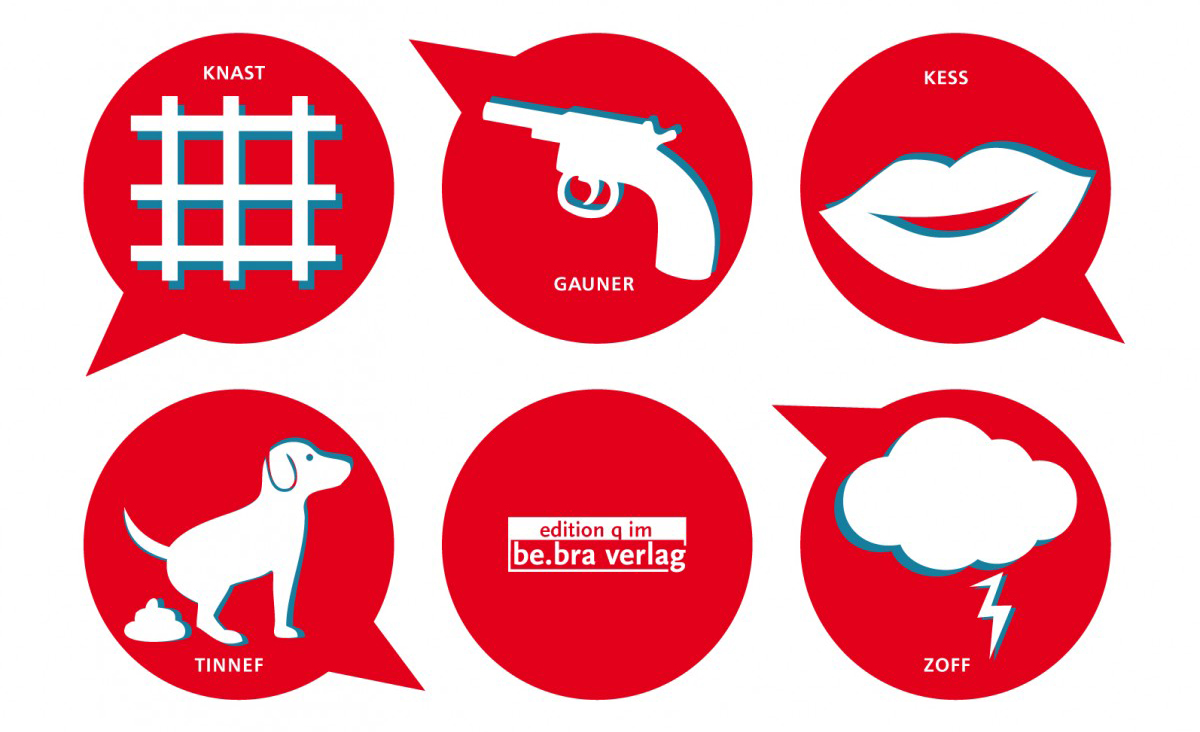

How German Jews and Non-Jews Laughed at Each Other in Not-So-Private Languages

“Good Lord, the Christian woman understood!”

Is a Jewish Language Really Still Spoken by Non-Jews in Bavaria?

Only in Schopfloch, as far as I know, have a large number of originally Jewish words survived in the speech of the local populace to this day.

Why English-Speaking Jews Call It "Passover" Rather Than "Pesah"

One never hears Jews speak among themselves of Sukkot as the holiday of Booths, or of Rosh Hashanah as New Year’s Day. Why the difference?

The Connection Between a Just-Discovered Ancient Hebrew Inscription and Modern Yiddish

“An earthquake in biblical scholarship” is how the discovery has been described. That’s true, as are the connections it reveals between ancient languages and modern ones.

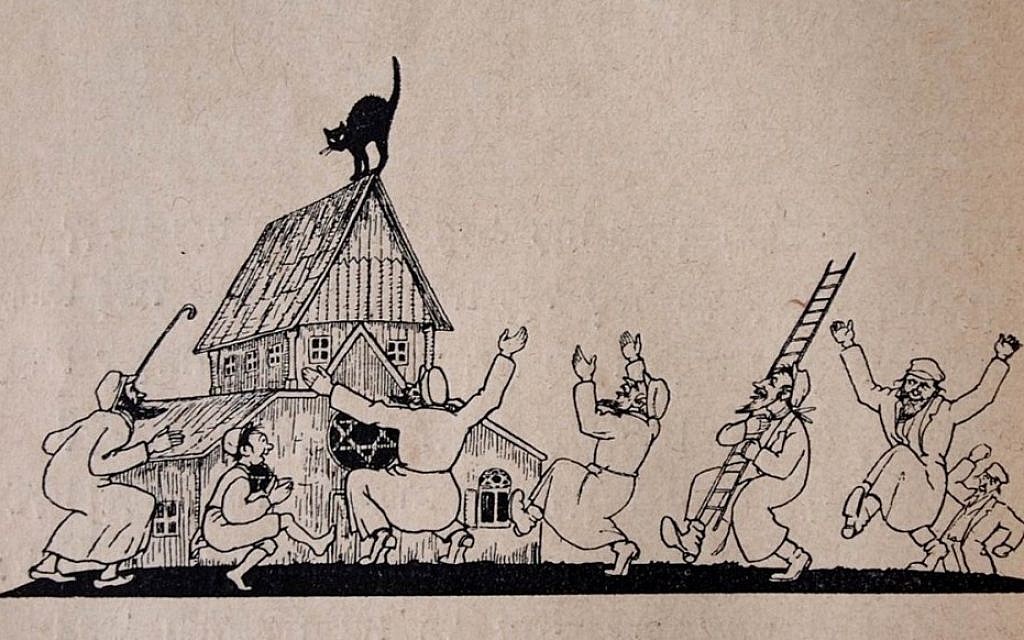

How Chelm Became the Jewish Town of Fools

Why was a random Polish shtetl singled out in the 19th century to become the home of fools in dozens of Jewish fables?

The World Knows It as Kiev or Kyiv. To Jews, It's Yehupetz.

The name is comical and magical at once, designating a city of broad boulevards and fancy shop windows known to Sholem Aleichem’s Tevye the dairyman and others.

Bread Versus Meat

The Arabic word for meat is nearly the same as the Hebrew word for bread. The source of the difference reveals much about geography, culture, and human settlement.

Race: a Word of Surprisingly Recent and Uncertain Origin

First surfacing in the 15th century as raza in Spanish, razza in Italian, and race in French before entering English in the 16th century, it has had six different etymologies proposed for it.

Why the Bible Uses the Word "And" So Much

The Hebrew of the Bible has many more ands than does modern English prose, a feature that’s surprisingly crucial to its literary power.

Should Moses Be Called Moshe?

A new edition of the Hebrew Bible edited by the late Jonathan Sacks Hebraizes its names in a way that bibles almost never do. Why, and what’s at stake?

Why Is “F---” Considered Unprintable?

Of all the expletives, the f-word alone continues to be partially censored. Perhaps that’s because it still connotes menace in a way that other expletives do not.

Jonathan Sacks and the Case of the Suppressed Stanza

The final, often-skipped stanza of the popular Hanukkah candle-lighting song Ma’oz Tsur presented the late rabbi with an unusual challenge.

The Legend of Colin Powell's Yiddish

The late statesman’s supposed knowledge of Yiddish bordered on the mythic. And myth it was, for his admirers routinely exaggerated his facility with the language.

Four Examples of What Happened to Yiddish After It Reached the United States

In some cases, changes were minor. In others, Yiddish phrases were transformed nearly beyond recognition.

More on the Differences Between "Jew," "Hebrew," and "Israeli"

And why each has been preferred in different times and places.

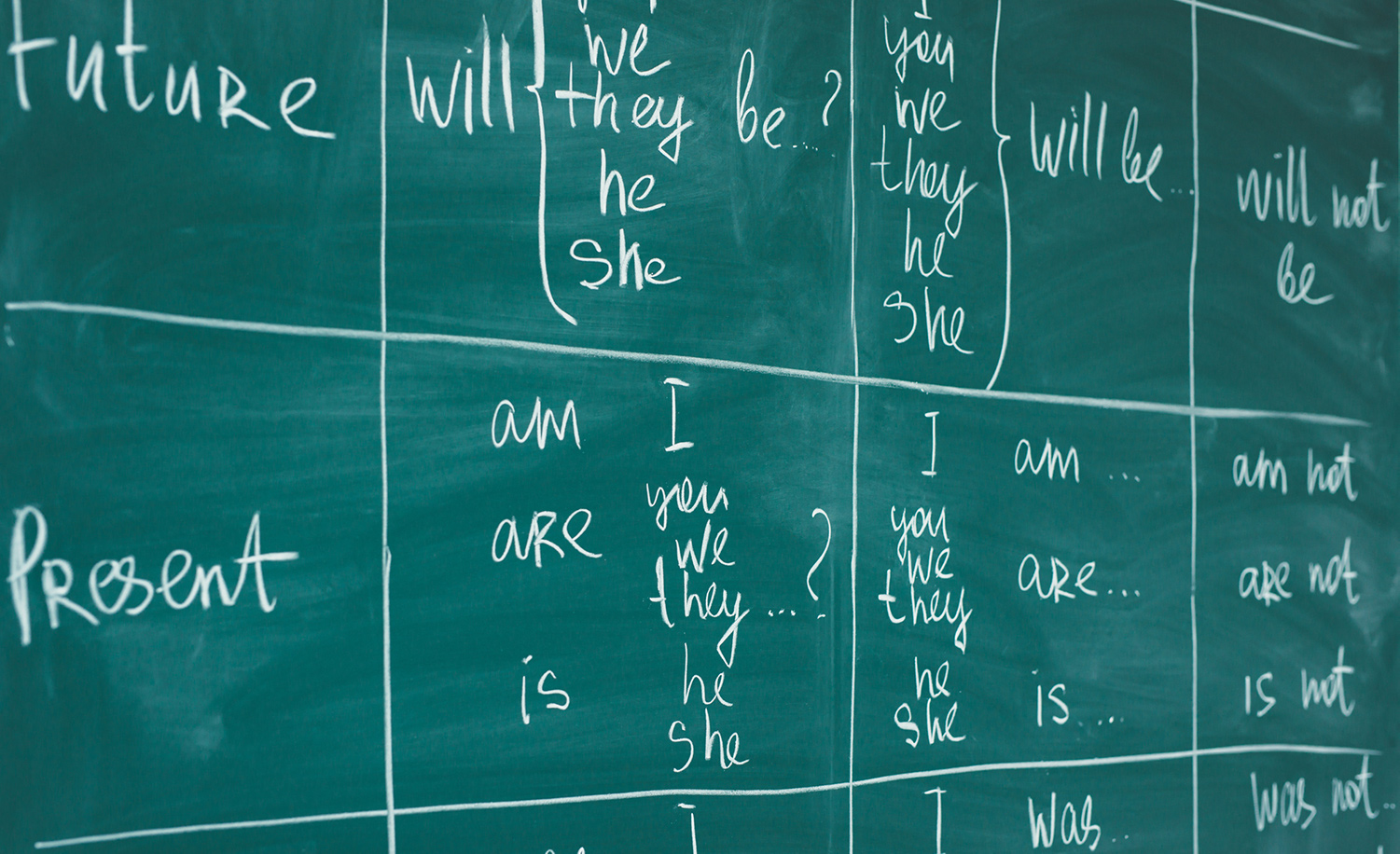

Should English Change Its System of Pronouns?

In a recent column, the eminent scholar John McWhorter celebrates a linguistic revolution in the offing. But at what cost, and to whom?

The Mystery Tucked Inside a Powerful High Holy Day Prayer

Apart from Kol Nidrei, no High Holy Day prayer is better known than Un’taneh Tokef. But there’s a puzzle at its heart.

Does Day Follow Night, or Night Follow Day?

God’s first creative proclamation was “Let there be light,” so it might seem that the day came first. But then why does the Bible say that “it was evening and it was morning?”

It's Not "Gaslighting" to Say that American Jews Are Moving Away from Israel

The trend is disturbing, no doubt. But owning up to it is better than staying in your own comforting reality.

The Gibberish a Madrid Doctor Mutters Going Into Church Is Really Hebrew Dating Back Six Hundred Years

“Oh, just some words that my family always says when we enter a church.”

How Should I Spell My Mother’s Name on Her Gravestone?

My late mother Pesya was the youngest child of immigrants to America from Kiev and Odessa, one reader writes. Here’s the story of her name.

"Israeli Arabs," "Palestinian Citizens of Israel," or "Israeli Palestinians"?

An impassioned letter about how to refer to Israel’s Arab minority.

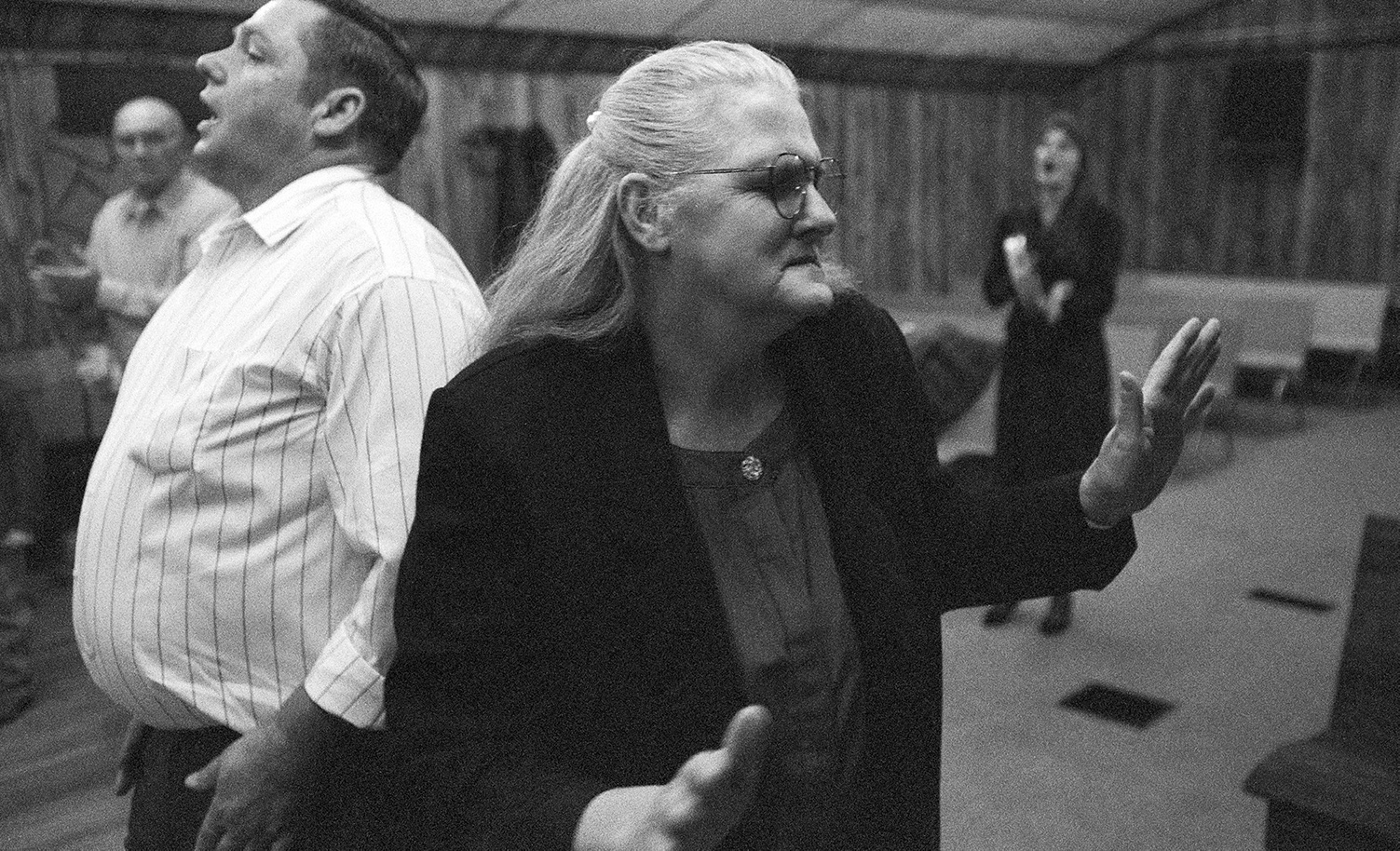

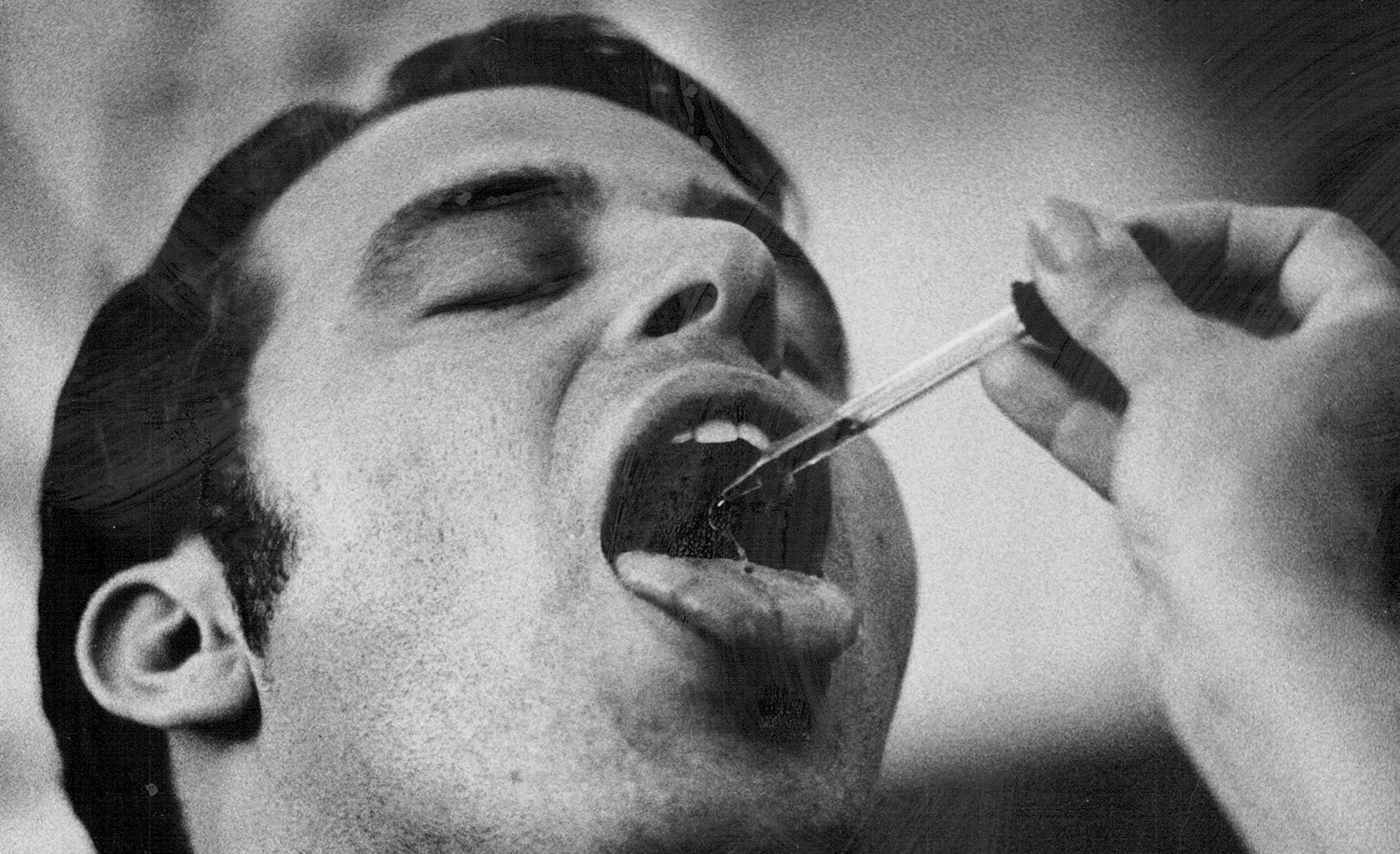

The Jewish Background of the Pentecostal Practice of Speaking in Tongues

According to the Talmud, when God handed down the commandments, he handed them down in every language at once.

What's the Reason for Hebrew's Mixed-Up Genders?

Quite a few masculine and feminine Hebrew words, when pluralized, take the form of the opposite gender. Why?

"Brandy" Comes from "Burned Wine," and Other (Judeo-)Linguistic Notes about Liquor

A brief look at some of the many Jewish words relating to alcohol.

The Holy and the Holey

Why should a Hebrew verb originally meaning to puncture have produced so many words relating to both the non-holy and to holes?

The Legend of Schulmann the Baker

A movement of aggrieved small-business owners has grown in Israel over the last year. But the origins of the Jerusalem baker it highlights as its chief example are shrouded in mystery.

Where "Kike" Comes From

We know that the slur has something to do with Jews traveling in rural America in the first years of the 20th century. Do we know more than that?

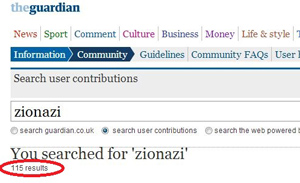

Facebook Shouldn't Ban Attacks on "Zionists"

Sure, the word is sometimes used as a pejorative term for “Jew.” But does anyone really think that banning it, as is reportedly being discussed, will prevent other terms from taking its place?

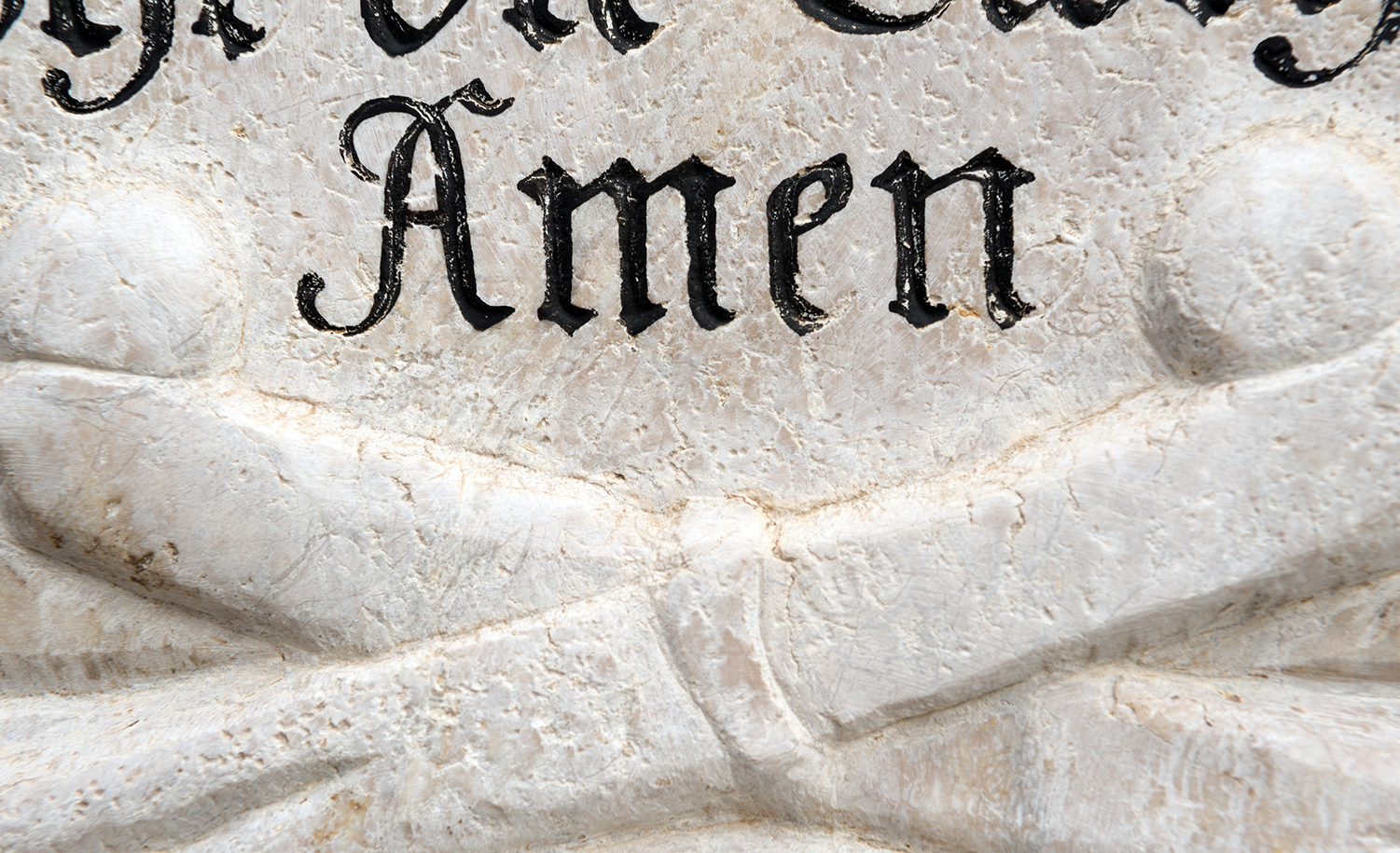

Why the Word "Amen" Has Changed So Little in Its 2,500-Year History

Its meaning in the Bible is “Truly said!” or “So be it!” After that it acquired its intense liturgical emotion, and then hasn’t changed much since.

Is There Any Reason the Last Digit of the Jewish Year and Last Digit of the Civil Year Are the Same?

From now until next September 6, we will be living in 5781 and 2021. Is that an accident, or is a deeper synchronicity at work?

Israel's Changing Relationship with Those Who Leave It

As tracked through the waxing and waning value of the Hebrew words for “departees” and “descenders.”

Why Don't Israelis Like the Word "Aliyah" as Much as They Used to?

In anti- and post-Zionist circles, the verb of choice for immigrating to Israel has been replaced by something less romantic.

Kamala, Mamale

Why do Yiddish speakers refer to children by terms of endearment seemingly meant for adults?

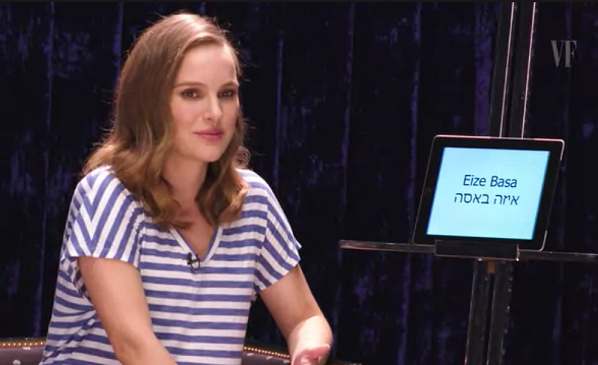

How Good Is Gal Gadot's Hebrew School?

The Israeli actress recently released “Gal Gadot Teaches You Hebrew Slang,” a short video from Vanity Fair. She turns out not to be such a good teacher, but it doesn’t matter much.

Do All Human Languages Derive From A Single Source?

Some paleolinguists have floated the idea of an original human language they call “Proto-Sapiens.” Is that what our ancestors were speaking when they built the Tower of Babel?

Jewish Holiday Greetings Don't Make Much Sense

Why Are the High Holy Day Services so Long?

The liturgy of Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur is full of liturgical poems that stretch the bounds of the Hebrew language and the patience of worshipers.

Hebrew Infusion vs. Hebrew Immersion in American Jewish Summer Camps

When one Jewish summer camp “bombed” another with leaflets excoriating its lack of commitment to Hebrew and Zionism.

Adin Steinsaltz's Glimpse into the Way That All Jewish Languages Work

Whether it’s Judeo-Arabic, or Judeo-Italian, or Judeo-Spanish, or the Judeo-German better known as Yiddish, they all mix in varying amounts of Hebrew.

Israelis Love to Call Each Other Cossacks Who've Been Robbed

A versatile fellow, this Cossack, identified simultaneously with Israel’s prime minister and his bitterest opponents! Who is he and who robbed him?

American English's Love Affair with the Yiddish Word "Meh"

A brief history of an indifferent word.

Why Do Israelis Have So Many Words for "Wear," and Which One Applies to Wearing One's Coronavirus Face Mask?

In English, one “wears” just about everything, from clothes to hats to perfume. In Hebrew, there’s a different verb for each of these items and more.

The Origins of the Phrase "Kangaroo Court" Have Been Hiding in Plain Sight

Elaborate comparisons between the stare of the judge and the stare of the kangaroo, begone.

Why the Word “Poodle” Was Banned from Use on the Floor of the Knesset

Israeli politicians have in recent decades become obsessed with calling each other poodels.

How "Anti-Semitism" Replaced "Jew-Hatred" and Why It Shouldn't Have

Looking back from the 21st century on an etymological decision from the 19th century, let us utter an “alas.”

The Truth about the Controversial New Translation of the Bible

Even though it takes liberties rendering the original text, a new Danish Bible breaks from anti-Semitic Christian replacement theology in a far clearer way than ever before.

"We Made It Past Pharaoh" Is the Israeli Version of "Keep Calm and Carry On"

A look at the morale-raising expression of choice in today’s Jewish state.

The Plague-Words of the Bible

Is there a difference between pestilence and plague?

How "Lovingkindness" Got So Popular, and So Far From Its Jewish Roots

A derived translation of the Hebrew Bible’s ḥesed, which focuses on action and deeds for others, lovingkindness as understood today focuses on internal feeling.

Why There Was Never an Italian "Yiddish" (and Why There Will Never Be an American One)

An Italian Yiddish was never in the cards, as the case of “Judeo-Mantuan” makes clear, because Jews were more closely integrated into Italian society than they were in Eastern Europe.

There Are so Many Yiddish Expressions for Going Bankrupt

And most of them reveal a hidden admiration for the person who’s had the wit and the grit to get away with it.

Are Biblical Hebrew and Modern Hebrew the Same Language, or Two Different Ones?

What separates language from language, and language from dialect.

Who Pisseth against the Wall?

Why the felt need to excise profanity from the Bible is fundamentally inane.

The Controversy Over the Origins of the Word "Ghetto"

For a word that is, in terms of its linguistic history, a relatively recent one, ghetto’s origins have been an unusual source of contention and uncertainty.

Why There Are So Many Ways to Spell Hanukkah

English is a language notorious for its strange spellings, and its speakers are more willing to tolerate aberrations than are speakers of other languages.

Some Rare Words for Rare-Word Buffs

Let us sing of rodomont, Sinon, proditomania, and, in particular, grobian.

Did the Saracens Get Their Name from the Biblical Sarah?

That’s what the rumor is. The truth about the ancient Arabic-speaking tribe is a little different.

Who Presides Over the Dead in Judaism? His Name Is Dumah.

And what you need to know in case you ever encounter him.

How Cappuccino Got Its Name, and What It Has To Do with the Coat Worn by Ultra-Orthodox Jews

One word got turned upside down and downside up again.

Most Wars Don't Get Named Until Years After the Fighting Is Done. Others, Like the Yom Kippur War, Are Different.

Unlike, say, “World War I,” the “Yom Kippur War” caught on from the start and never faded. Aside from its naturalness, it has an associational richness that no other names could match.

It's Time to Talk About Moons and Months

Why the words for both are so similar in so many languages, and why Hebrew has turned out to be the rare exception.

It's the Circle of Bread

The circular, braided bread known as challah has a twin. It originated in Greece, was picked up by Mediterranean Jews, traveled with them to Europe, and possibly back to Greece.

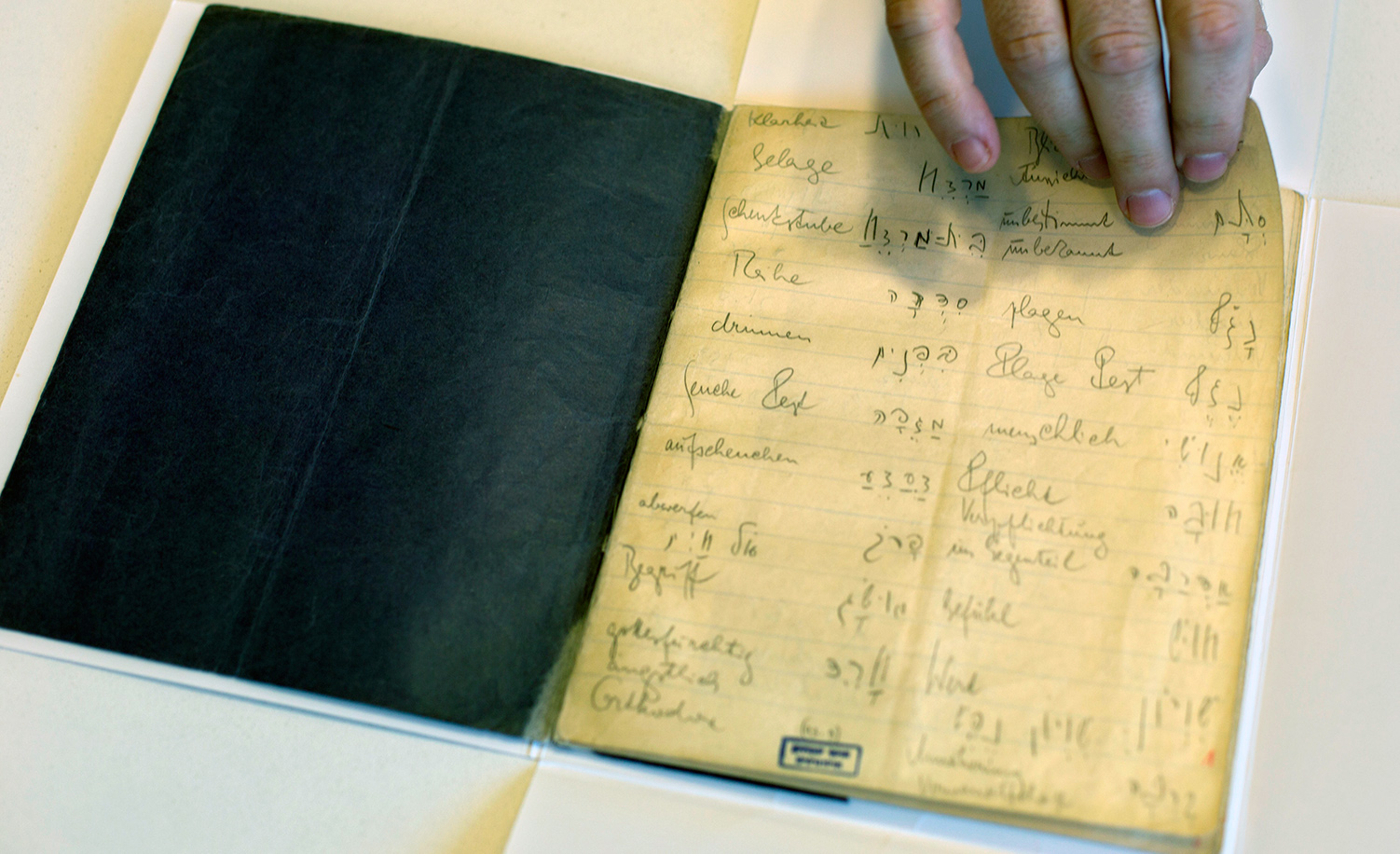

Kafka Knew Much More Hebrew than Previously Realized

A letter from recently opened archives of the great writer makes clear how seriously he took the language, and by extension a possible move to Palestine.

Why Does the Hebrew Bible So Often Refer to God as "Lord of Hosts"?

Host means army, but who were God’s armies?

The Meaning of Occupation

We hear a lot about “the Occupation” these days. There’s no need to say which. But where does the term come from, and how much is it worth?

What Are Those Floating Dots Doing in My Hebrew Bible?

Amid the familiar clutter of vowels and cantillation marks, a few strange dots appear. They have no obvious function, and yet they go back thousands of years. Their purpose is . . .

This Word Goes Back 4,000 Years and Spans Over a Dozen Languages

Variations of Hebrew’s misken, meaning “poor” or “unfortunate,” can be found from Italian to Swahili to Tagalog and far beyond.

Whatever Happened to Spoken English?

What you notice when returning to your native country after many years away: everyone starts sentences with “So” and ends them with a question mark.

Mies van der Rohe's Misbegotten Change of Name

Before becoming linked to the famous architect who was trying to escape it, the German word mies (rotten) made its way from Hebrew, to Yiddish, to a thieves’ argot called Rotwelsch.

The Real Meaning of "Hasbarah" (and Hasbarah)

Anti-Zionist conspiracy theorists, look away!

No One Knows for Sure What the Original Matzah Was

Not packaged, not square, not oven-baked: that’s what it wasn’t. But what it was and where the name for it comes from is still something of a mystery.

How the Names of Israeli Political Parties Became So Jingly

It’s part of a trend away from names that once projected clear identities (Workers’ Party) and toward the politics of advertising (There Is a Future).

When Nonsense Syllables Make Perfect Sense

Take, for instance, the word tararam, meaning—what else?—“fuss” or “hullabaloo.”

The (Shockingly Low) Literacy Rate of Jews in Eastern Europe

There were many more illiterate Jews in the Tsarist empire than we tend to think there were.

Last Month Philologos Asked for Language Help, and Got It

A Mosaic reader was able to solve the mystery of the Yiddish expression tapn a vant, “to grope a wall.”

They Call It "Fake News" in Other Countries, Too

From Hebrew to Spanish to German to Italian and onward, the term is now as international as Coca-Cola.

Can Anyone Advise Us on the Origin of the Yiddish Phrase "Touching a Wall"?

A chance to help our language expert.

Did This Odd Hebrew Expression Come from an Afro-American Folktale?

The many hypothesized sources for the saying, “To have butter on one’s head.”

The Movement to De-Gender Hebrew is Linguistically Mad

It is practically impossible to utter a complete sentence in Hebrew that lacks gender.

Why "Hanukkah Gelt" and not "Hanukkah Money"?

It sounds less mercenary—which is probably also why real coins eventually gave way to chocolate ones.

When Did We Begin to Talk about Victims of Misfortune or Adversity as "Survivors"?

It probably started with the term “Holocaust survivor.”

What's with the Hebrew Expression "To Jump over One's Bellybutton"?

The tale of the pupik.

Some Notable First-Century BCE Palestinian Jews With Greek Names

A recent archaeological discovery in Jerusalem reminds us that Jews once bore names like Antigonus, Aristobulus, and, possibly, Daedalus.

There's a Strange Grammatical Difficulty with the Opening Verse of the Bible

It could suggest a different story about the creation of the world.

Philologos Mailbag: Readers Help Solve the Pepys Puzzle

A tip from a Mosaic reader helps pin down what the great diarist was up to on the day of his famous synagogue visit.

The Mystery* of Simhat Torah 1663, at the First Synagogue in England in 350 Years

*What worship service did the great diarist Samuel Pepys actually witness?

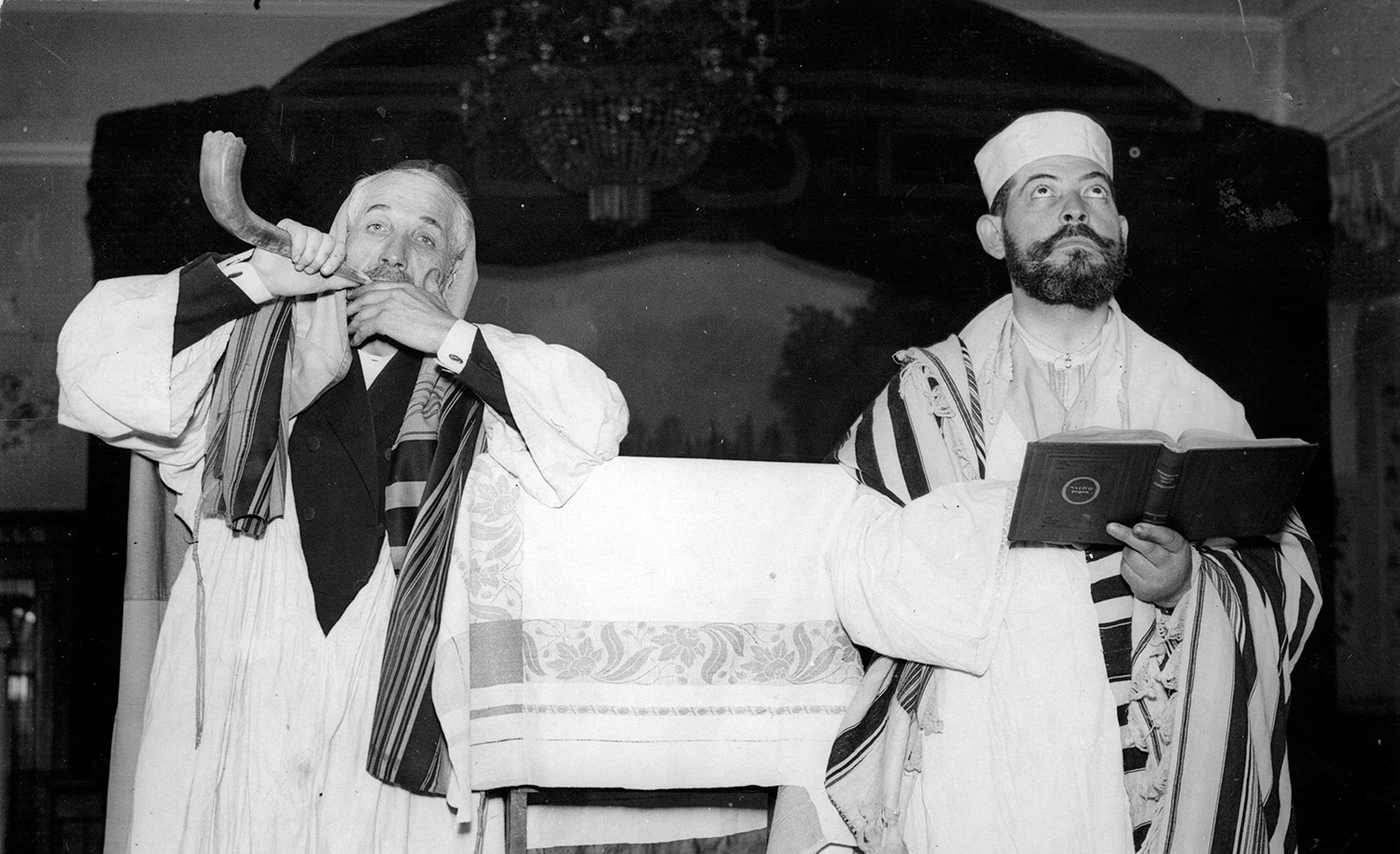

Where Do the Names of the Shofar Calls Come From?

At least one of them might stem from the days when Jews ululated.

Why There's No Word in the Hebrew Bible for "Spirituality"

For Judaism, the outward life of religious behavior comes first.

Israeli Arabs Are Speaking More Hebrew, and That's a Good Thing

A country of Jews, Muslims, Christians, and Druze all speaking Hebrew as their native tongue? For anyone genuinely interested in Israel’s welfare, it would be a dream come true.

Help: My Husband Passed Away, and I Want to Reconstruct the Bedtime Prayer He Taught our Children

Philologos is quite certain the words of the prayer are in German, not Yiddish. But beyond that?

Do We Take Pleasure, or Do We Scoop It Up?

The hidden roots of the Yiddish-American expression “to shep nakhes.“

The Real Zionist Planters' Society in James Joyce's "Ulysses"

The curious case of Agendath Netaim, which the half-Jewish Leopold Bloom spends a whole day considering.

Where Do Hebrew Acronyms Come From?

Medieval and modern Hebrew are unusually rich in abbreviations, but in a manner that is the reverse of English.

The Journey to Jewtown

The origins of two strange names for French villages that are now suburbs of Paris.

Do These Similar-Sounding and Similar-Meaning Hebrew Slang Words Come from the Same Place?

Of shlukh and shlokh.

How and Why Jews Hebraized Their Family Names at the Founding of Israel

“If there is no overriding reason for the Major to retain an awkward-sounding German name that our people finds hard to pronounce, . . . he [should] change it to a Hebrew one.”

Has the English Translation of "Pharaoh's Heart Was Hardened" Been Wrong All Along?

Figuring out the right way to characterize Pharaoh’s heart.

The Yiddish–Dutch–German "Smallpox" Exchange

Which language was patient zero for the old expression, “We’ve been smallpoxed and measled”?

Turns out Everybody Likes to Talk about an Aliyah of the Soul

But not Philologos.

What's with the Talk about an Aliyah of the Soul?

A strange new case of linguistic evolution.

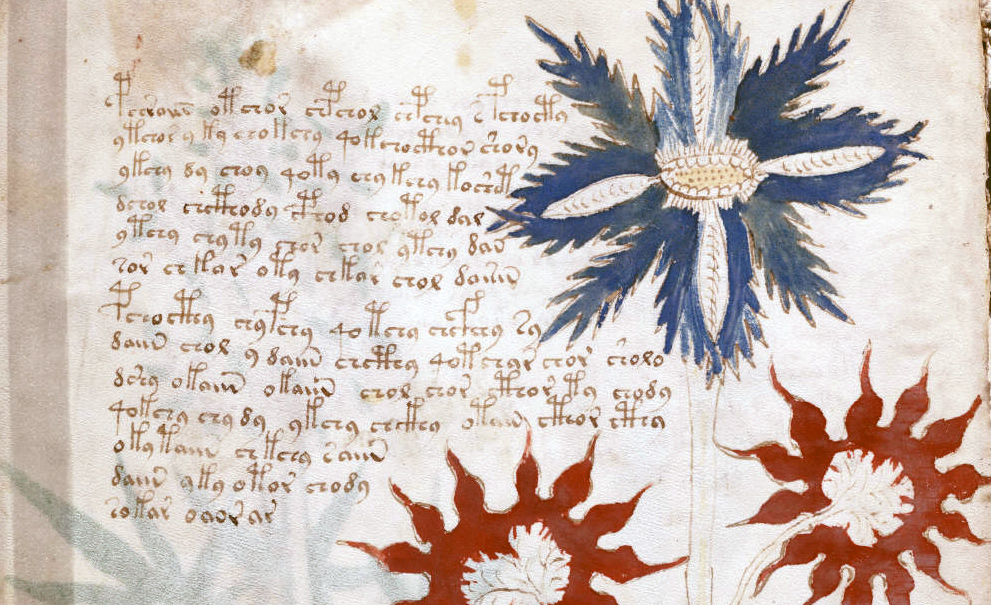

No, the Mysterious Voynich Manuscript Is Not Written in Hebrew

Despite the silly claims of two computer scientists.

Swearing in Time and Place

In Hebrew, Arabic, English, German, or any other language, taboo words are curious things.

Why the Terms CE and BCE Replaced AD and BC, and Why Jews Care About It

It’s not why you think.

Judah the Maccabee, Judah the Mace-Man

A modest suggestion for a new way of thinking about the original meaning of the word “Maccabee.”

Why Does “Making” Mean What It Means for American Ashkenazi Jews?

If you don’t know what it means, you can probably figure it out. (Or you can read this column.)

No, the Book of Joshua Does Not Tell of a Rare Solar Eclipse

Despite the claim of two recent scientific papers.

The Famous Israeli Accent, and How It Came About

“I em verry heppy to mit you end yourr femily in yourr hawm.”

What's a Kvitl, and Why Wish Anyone a Good One?

“A gut kvitl!” East European Jews once said to each other in the days just before and during the holiday of Sukkot, and many still do. What does it mean?

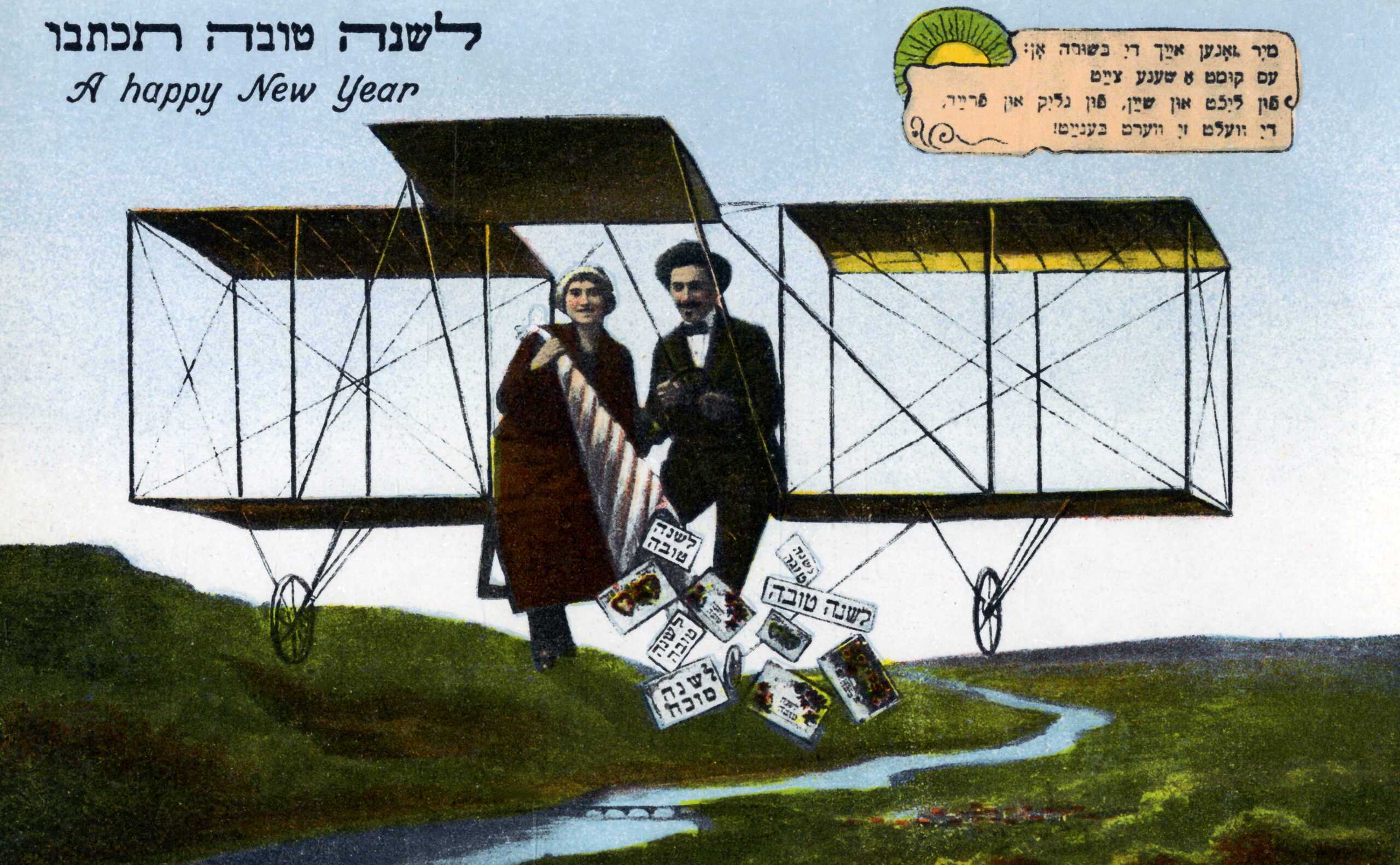

Rosh Hashanah Greetings, Yiddish-Style

The products of the Yiddish greeting-card industry are a reminder of how wonderfully varied was the world of Yiddish-speaking Jewry.

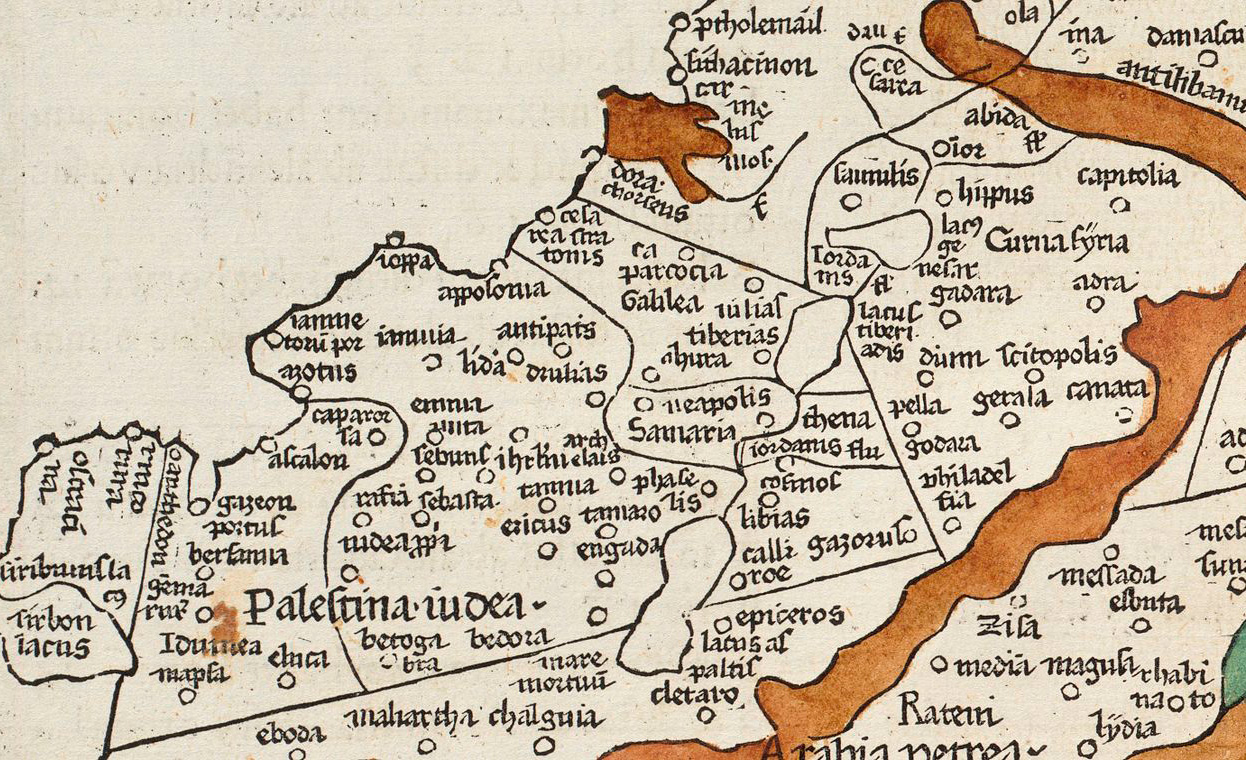

The Jewish (and Not-So-Jewish) History of the Word "Palestine"

There’s a lot in this name.

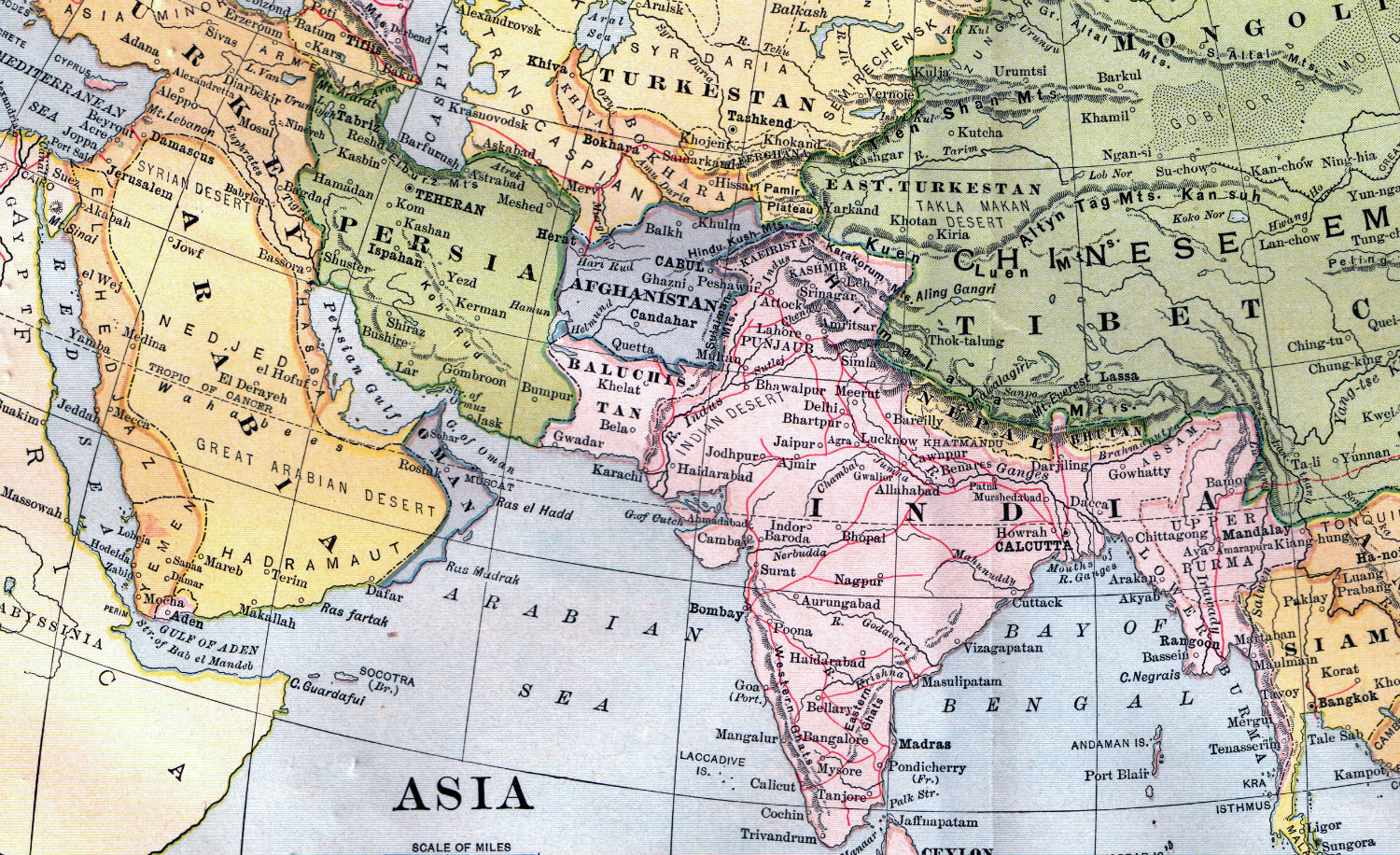

Did King Solomon Trade with India?

On the possible whereabouts of Ophir and Tarshish, and how to get there by ship from Palestine.

In the Year of the Small Count

On the once-prevalent practice of rendering Hebrew publication dates by means of numerically coded verses from the Bible.

Why Are Extremely Large Wine Bottles Named after Biblical Kings?

The convoluted story of jeroboams, rehoboams, methuselahs, and more.

How Modern Hebrew Developed a Full-Blown Slang in Just a Hundred Years

In part, it borrowed extensively from the slangs and vernaculars of other languages. Consider the case of de la shmatte.

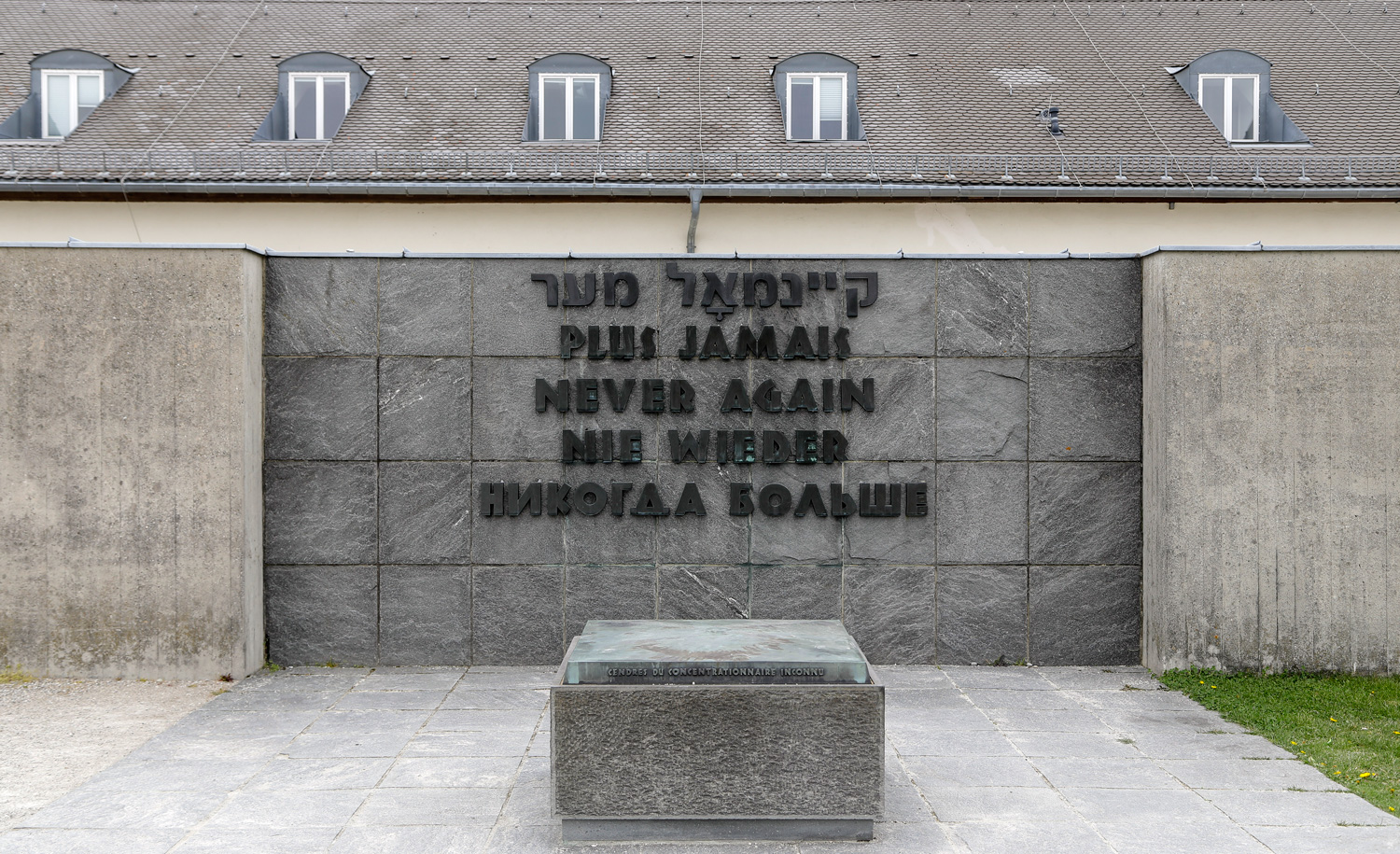

What Is the Source of the Phrase "Never Again"?

Some say its author was Meir Kahane, the founder of the Jewish Defense League. Is that right?

Who Is the Biblical Stranger, and What Should the Bible's Teaching Mean Today?

The shifting historical meaning of “Thou shalt not oppress a stranger.”

Some Yiddish Words Jump into American English Quickly. Others Take Much Longer.

The process results from, in equal measure, Jewish separateness and Jewish assimilation.

Of Noodge and Nudge, of Slob and Schlub

A look at the phenomenon by which Yiddish words become English words under the influence of other, similar-sounding English words.

There's No Need to Reclaim the Word “Jew”

Contrary to a Times column, the reason people say “he’s Jewish” rather than “he’s a Jew” has nothing to do with anti-Semitism. It’s just a quirk of grammar, and it’s not unique to Jews.

You Didn't Know There Was Another Ahasueros?

Starting in the 16th century, this Ahasueros has personified the legendary figure of the “Wandering Jew,” symbol of the accursed Jewish people. How come?

Why Yiddish Was Often a Source for Thieves' Slang in European Languages

What we learn from the story of the Russian phrase shakher-makher, or wheeler-dealer.

The Journey of the Word "Artichoke" Shows Folk Etymology at Its Most Creative

A linguistic investigation prompted by a meal in Rome of carciofi alla giudia.

How Do You Say "Pirkey Avot" in English?

The title of the Mishnaic tractate is commonly translated as “The Ethics of the Fathers.” But how did it get that name? And could “fathers” actually mean “principles,” and “ethics” mean “sayings”?

The Variety and Universality of Nicknames

Different languages employ different methods of generating nicknames, but they all satisfy the same two needs: to show special affection and to demonstrate special intimacy.

Why the Word for Wine Is Similar in So Many Languages

There’s Greek oinos and Hebrew yayin, to say nothing of such farther-flung cognates as Swahili mvinyo and Maori waina. Is there a common root?

The (Not-So) Jewish Roots of Esperanto

Created by an East European Jew disillusioned with Zionism and Hebrew, the language was meant to unite humanity in a spirit of brotherhood.

Language Evolves, but Kinship Words Like "Uncle" and "Grandchild" are Surprisingly Durable

Why certain terms having to do with the basics of life are less prone to linguistic change than others.

How a Hebrew Word Made Its Way into the Speech of a Remote Italian Village

Why are my friend’s Italian neighbors calling a house a bayta?

The Origins of the Precept "Whoever Saves a Life Saves the World"

And what they tell us about particularism and universalism in Jewish tradition.

Why the Israelites Expelled a Scapegoat into the Wilderness on Yom Kippur

Who or what was Azazel?

How Jewish Leap Years Came to Be Calculated

The method, developed by the Babylonians and kept alive by medieval Jews, is known in Hebrew as the “secret of impregnation.”

How Israeli Backpackers Imported an Element of Spanish into Hebrew

What nahagos, the casual term for “driver,” tells us.

Cupping in Jewish Life and Law

A form of folk medicine now in the news thanks to Olympic athletes like Michael Phelps, cupping has a long history in Judaism.

How English Words Get Entrenched in Israeli Speech, and How to Get Them Out

Why the Hebrew word for “shaming” (as in “Facebook shaming”) should not be sheyming.

The False Ideas in the Phrase "Jew by Choice"

Now used to describe converts to Judaism, the term misleadingly suggests that Jewishness inheres more in certain selective beliefs than in Jewish peoplehood.

Star of David, Star of Solomon, or Star of Sheriff?

How the hexagram became a Jewish symbol.

How the Books of the Hebrew Bible Got Their Names

Some are named for their first word, others for their first significant word. What about the rest?

How Did Yiddish Words Make Their Way into German?

A centuries-old tale of complicated, ambivalent, and, sometimes, covertly intimate relationships between a largely anti-Semitic Christian society and its Jewish minority.

Where Does the Phrase "Am Yisra’el Ḥai" Come From?

Popular today at weddings and bar-mitzvahs, the words, meaning “the people of Israel lives,” trace all the way back to the story of Joseph.

How Many Plagues Were There Really in Egypt?

The answer depends on how one punctuates the Bible’s Passover story.

The Twisting Tale of the Yiddish Term for B----

How a bizarre talmudic passage led to klafte, the derogatory word for an unpleasant woman.

Who're You Calling a "Zio"?

As news reports from Britain confirm, a new anti-Jewish slur is making the rounds. Where did it come from?

Looking for Satan in All the Wrong Places

Some think the Devil can be found in the Hebrew Bible. Are they right?

From "Awesome" to "Awe-Inspiring": How Words Become Devalued

Like animals, words have an ecology. As one is driven out of its traditional habitat, others move into the space that has been vacated.

Why There Are More Yiddish Idioms in Israeli Hebrew than in American English

By the time Yiddish-speakers arrived in America and pre-state Palestine, English already had a rich vernacular, while Hebrew had none at all.

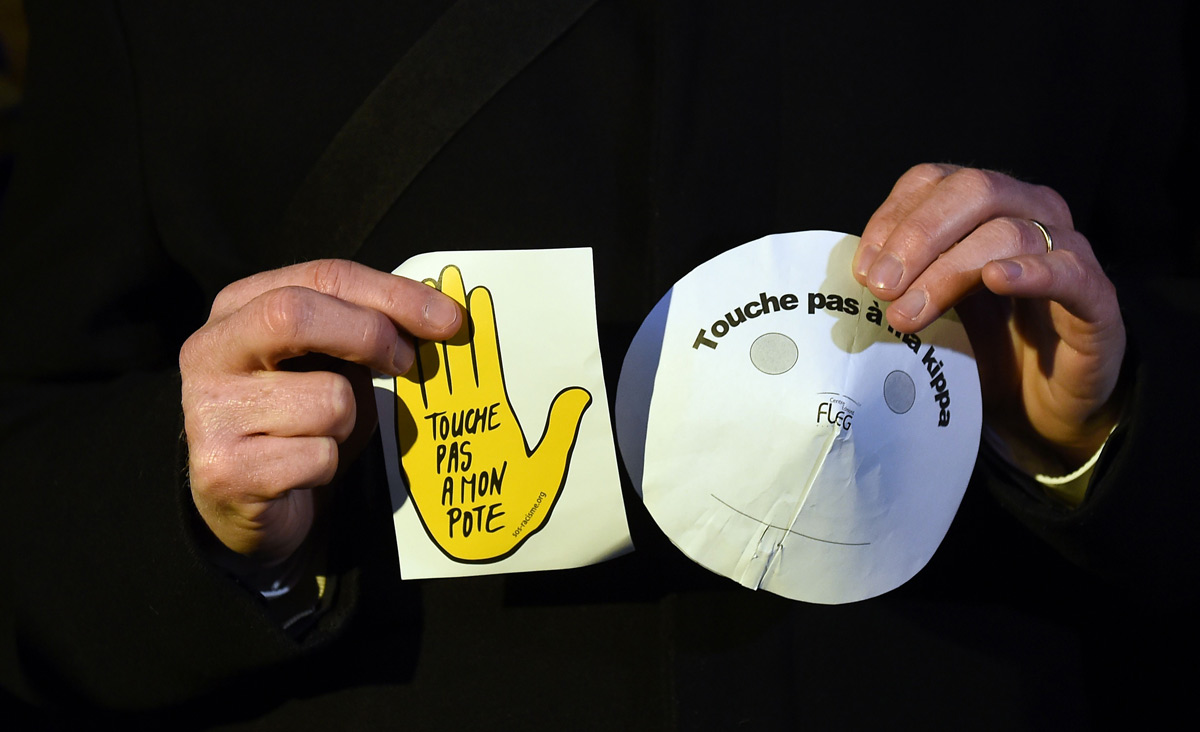

Skullcap, Kippah, or Yarmulke?

Three different words for the same Jewish head covering. Are they interchangeable?

Is It Asking Too Much to Love Your Neighbor as Yourself?

Romantic, idealistic Christianity says no. Sober, practical Judaism says yes.

The Bible Says to Love Your Neighbor as Yourself. But What Does Neighbor Mean?

The answer hasn’t always been clear.

The Tree of Knowledge of Positivity and Negativity

How to translate the rabbinic term yetser ha-ra—and how not to.

Why Is the Beta Israel Term for God Different from the Hebrew Terms for God?

The answer might help uncover the origins of Ethiopian Jewry.

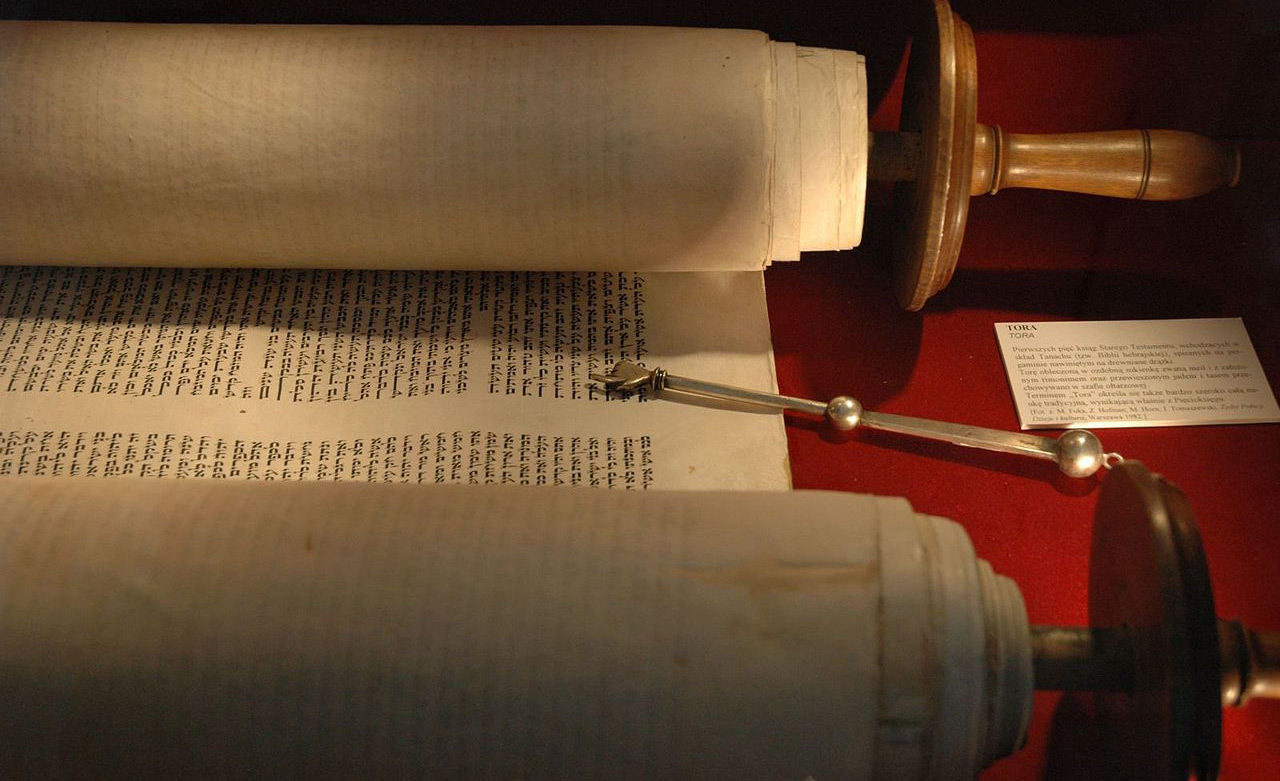

Who's Right, Me or My Cantor?

My cantor told me the plural for yad, the Hebrew word for Torah pointer, is yadot. I think it’s yadayim. Who’s right?

Why Does My Family Chant Yiddish-Hebrew Toasts at Celebrations?

“Fire is fire, meat is meat.” But what does it all mean?

Whatever Happened to Gut Yontif? Why Jews Started Saying Ḥag Same'aḥ

The history of holiday greetings.

The "Keseh" Conundrum

There are three Hebrew expressions for the days from Rosh Hashanah through Yom Kippur. Two are well-known. The third? No one’s quite sure what it means.

No, the Lilliputians Didn't Speak Hebrew

It was widely reported this month that a professor in Texas had “decoded” the strange language spoken in Gulliver’s Travels. He did no such thing.

The Voyage of the Dawn Etymologist

Philologos sets sail to discover the roots of the Yiddish word kayor.

The Girl with the Yiddish Tattoo

A near-indecipherable tattoo on a woman’s leg helps unravel a mystery surrounding the 1943 anthem of the Jewish resistance.

What's so Bad about Paganism?

Even in our increasingly post-religious age, “pagan” remains for most people a derogatory word. Why?

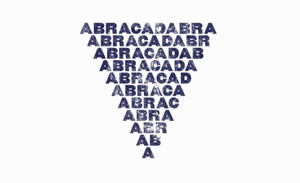

Are the Origins of "Abracadabra" Jewish?

The first written reference to the magical utterance was in a Roman text. Did it have earlier roots?

Did Israel's President Really Refer to Reform Judaism as "Idol Worship"?

Or was he mistranslated?

Why the King James Version of the Bible Remains the Best

The 400-year-old translation is denigrated because of its archaic language. That’s one of its greatest strengths.

The Paradox of the Transmission of Sacred Texts

Hebrew scribes take great pains to copy faithfully. But, as a passage in Proverbs shows, once an error creeps into the chain of transmission, it can be there forever.

How to Say You're Welcome in Yiddish and Other Languages

And why we say it at all.

Which Creatures Made Up the Fourth Plague?

Rabbi Yehudah says lions and bears. Rabbi Nehemiah says hornets and gnats. What does arov really mean?

How Lev Tolstoy Became Leo Tolstoy

Why do we Anglicize some names and not others?

Sorry, NYTimes—There Are Actually Five Hebrew Words for Debate

A common and dismaying misconception.

Who Kissed/Killed First?

Does the English idiom “kiss of death” come from the story of Judas, or from the Sicilian Mafia—or both?

Does the Word “Hacker” Come from Yiddish?

Is the tech term, as in computer hacker, connected with the verb hakn, meaning to chop?

On the Interpretation of Kebabchik

After a friend comes to him with a strange dream, Philologos wonders if the unconscious mind can do Hebrew numerology.