In all the justified outrage over Israel being charged in the International Court of Justice with committing genocide in the Gaza Strip, one thing has gone largely uncommented on. This is that the 1948 United Nations “Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide” on which the charge is based is so loosely and sloppily phrased that it might be taken to apply to most countries in human history that have warred against other countries, political entities, or armed groups.

Here are the preamble and first three clauses of Article II of the Convention, in which the crime of Genocide is defined:

In the present Convention, genocide means any of the following acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical [sic], racial, or religious group, as such:

(a) Killing members of the group;

(b) Causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group;

(c) Deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part.

The key phrase in Article II, repeated twice, is “in whole or in part.” What exactly does it mean to intend to destroy part of a national, ethnic, racial, or religious group in the ways described by clauses (a), (b), and (c)? Well, since those fighting in the ranks of Hamas are indisputably part of the Palestinian people, it could mean that any war fought to destroy them as described by Article II’s first three clauses could be construed as genocidal. And one could say the same thing about the Greeks fighting the Persians at Thermopylae, the English fighting the French in the Battle of Hastings, and the Allies fighting the Germans in World War II. All were doing so with the intent to kill, harm, or expose to risk of death part of a national or ethnic group.

To this, of course, it can be quite sensibly objected that, although the Genocide Convention does not (strangely enough) explicitly say so, its definition of genocide refers to civilian populations, not to military forces, and that it is toward the civilian population of the Gaza Strip that Israel stands accused of acting genocidally. Even with this objection in mind, however, genocide as defined by the Convention must be considered to have been committed innumerable times in the past. Siege warfare, to take one example, common throughout human history, has been fought precisely for the purpose of inflicting “conditions of life calculated to bring about the physical destruction in whole or in part” of those inhabiting the besieged sites. When the North blockaded Southern ports during America’s Civil War, its leaders knew that they would be depriving Southern civilians of food and medicines that would endanger the lives of at least part of them, to say nothing of causing them “serious bodily and mental harm.” Was the Union guilty of genocide? According to the United Nations Genocide Convention, it was.

Indeed, the killing of even a handful of people can theoretically be a genocidal act according to accepted legal interpretations of the Genocide Convention. Such a ruling was given in a 2015 verdict of the Appeals Chamber of a United Nations tribunal trying charges of genocide in the Serbian-Bosnian war. While overturning a Trial Chamber’s finding that the Serbian general Zdravko Tolimir’s murder of three Bosnian leaders in 1995 was genocidal, the Appeals Chamber upheld the Trial Chamber’s position that “the selective targeting of leading figures of a community may amount to genocide” if meant to further the destruction of that community “in whole or in part.”

It was the looseness of the Genocide Convention’s phrasing, especially the “in part” of Article II, that led the Ohio Northern University law professor Robert Friedlander, testifying at a 1985 session of the U.S. Senate’s Judiciary Committee convened to weigh Senate ratification of the Convention, to remark: “The designation of genocide found in the Convention is vague and overbroad, arbitrary and capricious, and unreasonable in construction and composition. Genocide, as defined by the Convention, can apply to just about anyone, doing almost any act posing almost any threat to virtually any type of victim.” Although the U.S. finally ratified the Convention in 1988, reservations like Friedlander’s delayed ratification for 40 years.

Titled “Why the Genocide Treaty Trivializes the Horror of Genocide,” a Heritage Foundation report on the Senate proceedings prophetically observed: “It [the Genocide Convention] will make a mockery of the civilized world’s condemnation of genocide. It will be a document, moreover, which will be used to harass and assaults those democratic nations which take seriously their signatures on treaties and which must contend with unfettered public opinion [and it] will be ignored by those nations which scorn democracy and are in fact those most likely to commit genocide.” Testifying at the same proceedings, the jurist and diplomat Grover Rees, then special counsel to the United States Attorney General, observed that the state of Israel was particularly susceptible to the Convention’s abuse, since “the most frequent charges of genocide during the postwar period have been those against Israel.”

One charge Rees had in mind was a UN General Assembly resolution of December 1982 in which the massacre of Palestinians earlier that year by Lebanese Christian gunmen in Beirut’s Sabra and Shatila refugee camps was declared to be an act of genocide. While Israel, whose forces had surrounded the camps, was not mentioned by name as the massacre’s perpetrator, the rest of the resolution made clear that it was considered responsible for it. Fewer than a thousand Palestinians were killed in the massacre, whose purpose was to avenge the assassination of Lebanon’s Christian president Bashir Jamayel, but since this met the requirement of destroying “part” of a “national group,” the General Assembly, by a vote of 123 to 0 with 22 abstentions, declared it genocide.

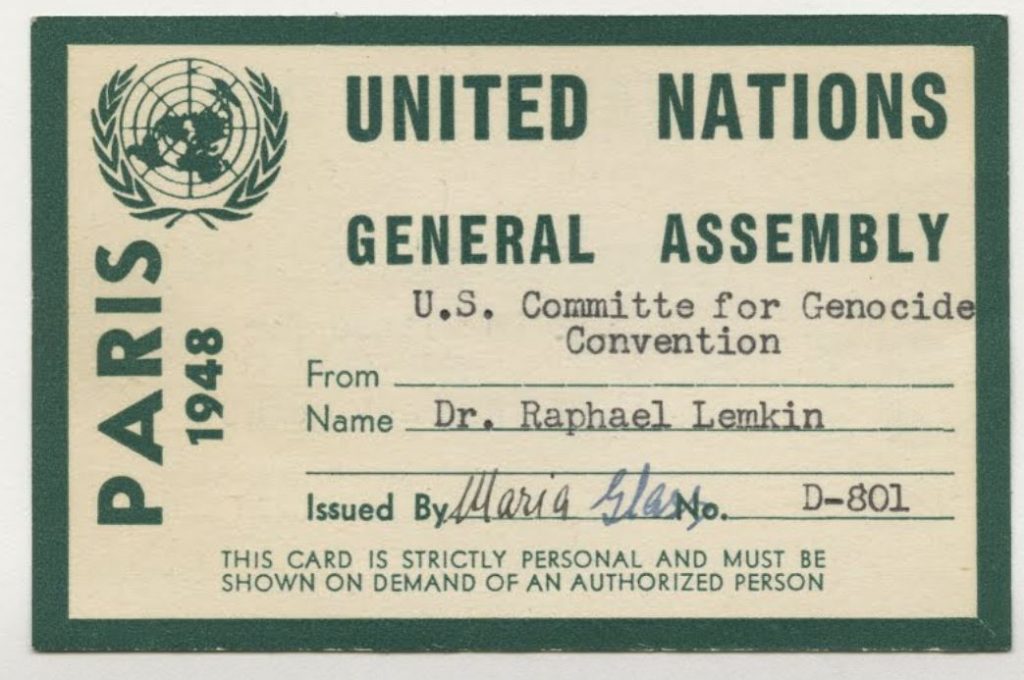

The irony of this is that Raphael Lemkin, the Polish-Jewish lawyer who coined the term genocide and fought tirelessly for the adoption of the Genocide Convention, did so precisely because there was no previous linguistic term or law applying to the attempted murder of a whole people, such as took place in the Holocaust. Lemkin was seeking to supplement the legal term “crime against humanity,” which had been used for mass killings like the Sabra and Shatila massacre as far back as the 19th century and was the charge brought against high-ranking Nazis in the 1946 Nuremberg Trials. An event like the Holocaust, which was far more extreme and much rarer than a simple “crime against humanity,” called, so Lemkin argued, for language of its own.

This is not to say that Lemkin thought the Holocaust unique. On the contrary, there would have been no need for a generic term for genocide had it been sui generis. In the 20th century, there were at least two other true genocides, the Turks’ attempted extermination of the Armenians during World War I and—long after Lemkin’s death—the Tutsis’ mass butchery of the Hutus of Rwanda in 1994. Neither succeeded entirely, just as the Nazi genocide did not. But the fact that many Armenians, Hutus, and Jews survived their intended extinction does not mean that their murderers would not have killed them all, rather than just a part of them, if they could have.

Lemkin was instrumental in formulating the 1948 Genocide Convention, and it may be that his support for the “in part” of Article II came from his wanting to be careful. It could have been argued, after all, that because the Nazis knew they could not murder every last Jew—the millions of Jews in America, for instance, were clearly beyond their reach—their intention was never to exterminate the whole Jewish people; adding “in part” to Article II thus prevented a legal defense on such grounds. The phrase was certainly not meant by the Convention’s framers to mean that the killing of any part of a people, no matter how small and even if undertaken with no intention of killing the rest of it, could be considered genocidal. For this, “crime against humanity” sufficed.

And yet this is exactly what the “in part” of Article II has come to mean and what the accusation of genocide against Israel is based on. This accusation, it hardly needs saying, would be slanderous in any case, since Article II also states that genocide exists only where there is an “intent” to commit it, and no sane observer can believe that Israel deliberately set out to kill or injure Gazan civilians while attacking Hamas strongholds, hideouts, and tunnels. Ultimately, trials like the International Court of Justice’s present one are about the hypocrisy of international politics, not the justice of international law. Special Counsel Rees knew this when he warned that Israel was “particularly susceptible” to the Genocide Convention’s inevitable abuse.

More about: Gaza War 2023, History & Ideas, Israel & Zionism, new-registrations