Got a question for Philologos? Ask him directly at [email protected].

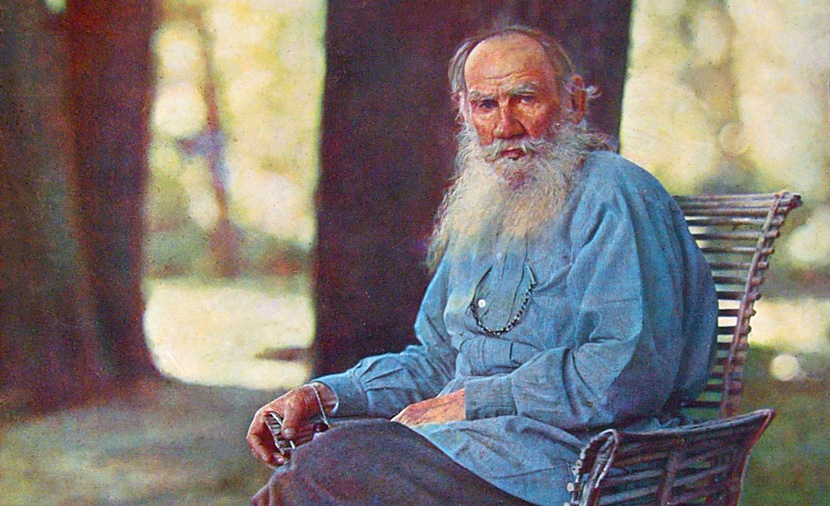

Margalit Tal of the Klau Library of the Hebrew Union College-Jewish Institute of Religion in Cincinnati has a question that is shorter than the name of her workplace. “When and why,” she asks, “did Lev Tolstoy become Leo Tolstoy?”

It would seem that Tolstoy, who had the given Russian name of Lev and the patronymic of Nikolayevich, was himself responsible for becoming Leo in English. A member of the nobility, he published his books in Russian as “Graf [Count] L.N. Tolstoy,” and when in 1878 the American translator Nathan Haskell Dole put out the first English edition of one of them, Tolstoy’s youthful war memoir The Cossacks: A Tale of the Caucasus in 1852, the name on the title page, phonetically spelled, was ” Lyof N. Tolstoy.” Dole’s 1889 translation of War and Peace did the same. But an earlier, anonymous French rendition of the novel, published in St. Petersburg in 1879, gave its author’s name as “Comte Léon Tolstoȉ.”

This was in itself a translation, the name Léon meaning “lion” in French as Lev does in Russian, and Tolstoy obviously approved of it and probably suggested it, since the St. Petersburg edition of La Guerre et la Paix was published, as stated on its title page, “with the authorization of the author.” And when a second English translation of War and Peace came out in 1904 in the now-classic version of Constance Garnett, a personal friend of Tolstoy’s who must have consulted him about it, Comte Léon Tolstoȉ was Anglicized to Count Leo Tolstoy. (Such an Anglicization had already appeared in Aline P. Delano’s 1894 English translation of Tolstoy’s The Kingdom of God Is Within You.) Although “Count” was eventually dropped, all subsequent English editions of Tolstoy’s books kept the Leo.

This was, it must be said, unusual. Dostoyevsky was always known outside of Russia as Fyodor, not Theodore, Chekhov as Anton, not Antoine, Antonio, or Anthony. The same has held true in recent centuries of practically every other well-know foreign author, painter, musician, or outstanding figure in other fields. Why should Tolstoy have wanted to be Léon or Leo rather than Lev?

Was he thinking of Russia’s Piotr Velikiy, called Pierre le Grand in French and Peter the Great in English, or of Ekaterina Velikaya, Catherine la Grande or Catherine the Great? Did he perhaps aspire to become a world-historical personage like them? Generally speaking, it is only the great whose names have sometimes been translated in passing from one language to another, so that apart from royalty, with whom it has been done commonly (e.g., Henry, not Henri, the First of France; William, not Willem, the Silent of Holland), we have in English such cases as Joan rather than Jeanne of Arc, Francis rather than Francesco of Assisi, and Christopher Columbus rather than Cristoforo Colombo or Cristóbal Colon. There are a few examples of this from modern times as well: Iosif Stalin is always Joseph in English and the current pope is Francis, too.

Yet Stalin, popes, and Tolstoy aside, modern name translations are almost never found in the public sphere. No one would dream of calling the French president Frank Hollande instead of François, or his Argentinean counterpart Christine Kirchner instead of Cristina. But has anyone noticed that, when they are not being Bibi and Buzhi, the two main contenders in Israel’s soon-to-be-decided electoral campaign are routinely referred to by the English media as Benjamin, not Binyamin, Netanyahu and Isaac, not Yitzhak, Herzog?

Is this mere coincidence? I’m not so sure. It’s true, of course, that Israeli politicians have not generally had their names translated in this way. Yitzhak Rabin and Yitzhak Shamir were always Yitzhak, Moshe Dayan never became Moses, and Shimon Peres isn’t Simon. Yet when one looks at contemporary history books, works of scholarship, and articles in the media, one encounters a curious phenomenon. Here are some entries culled by me from the index of a compendious 2002 collection of essays by noted scholars entitled Cultures of the Jews: A New History: “Bar Kokhba, Simon”; “Judah [not Yehuda] ha-Nasi”; “Ibn-Gabirol, Solomon” (not Shlomo); “Maimonides (Moses ben Maimon)”; “Abravanel, Isaac”; “Gaon of Vilna (see Elijah [not Eliyahu] ben Solomon [not Shlomo] Zalman)”; “Ba’al Shem Tov (Israel [not Yisra’el] ben Eliezer)”; “Kook, Abraham Isaac” [not Avraham Yitzhak]; “Tchernikhovsky, Saul” (not Sha’ul)”; etc. The list, needless to say, is partial.

Imagine picking up a book called Cultures of Europe and reading about Leonard da Vinci, Michael de Cervantes, John Sebastian Bach, John Jack Rousseau, Lewis van Beethoven, George William Hegel, Paul Picasso, and Frank Kafka! And yet this has been the norm in Jewish studies for the past 200 years and remains so, even though the scholars in question would never use anything among themselves but the Hebrew names that Jewish tradition has always used.

Why is this? The probable reason, I think, has been the desire of Jews to make accessible to the non-Jewish world a minority culture whose strange-sounding names become more familiar when translated into equivalents, like Israel, Judah, Moses, Solomon, and Elijah, that are known to most people from the Bible. Although it’s not necessarily any easier to say Johann Wolfgang Goethe than it is to say Yitzhak Luria Ashkenazi, the feeling has been that if Yitzhak becomes Isaac, readers will breathe easier—to say nothing of the TV viewers who will learn next week if Isaac beat Benjamin or vice-versa. I find this silly. Although Yehuda Halevi may be a bit more digestible in English as Judah, he is also a bit less himself. But I would say the same thing, I suppose, about Lev Tolstoy.

Got a question for Philologos? Ask him directly at [email protected].

More about: Arts & Culture, Leo Tolstoy, Philologos