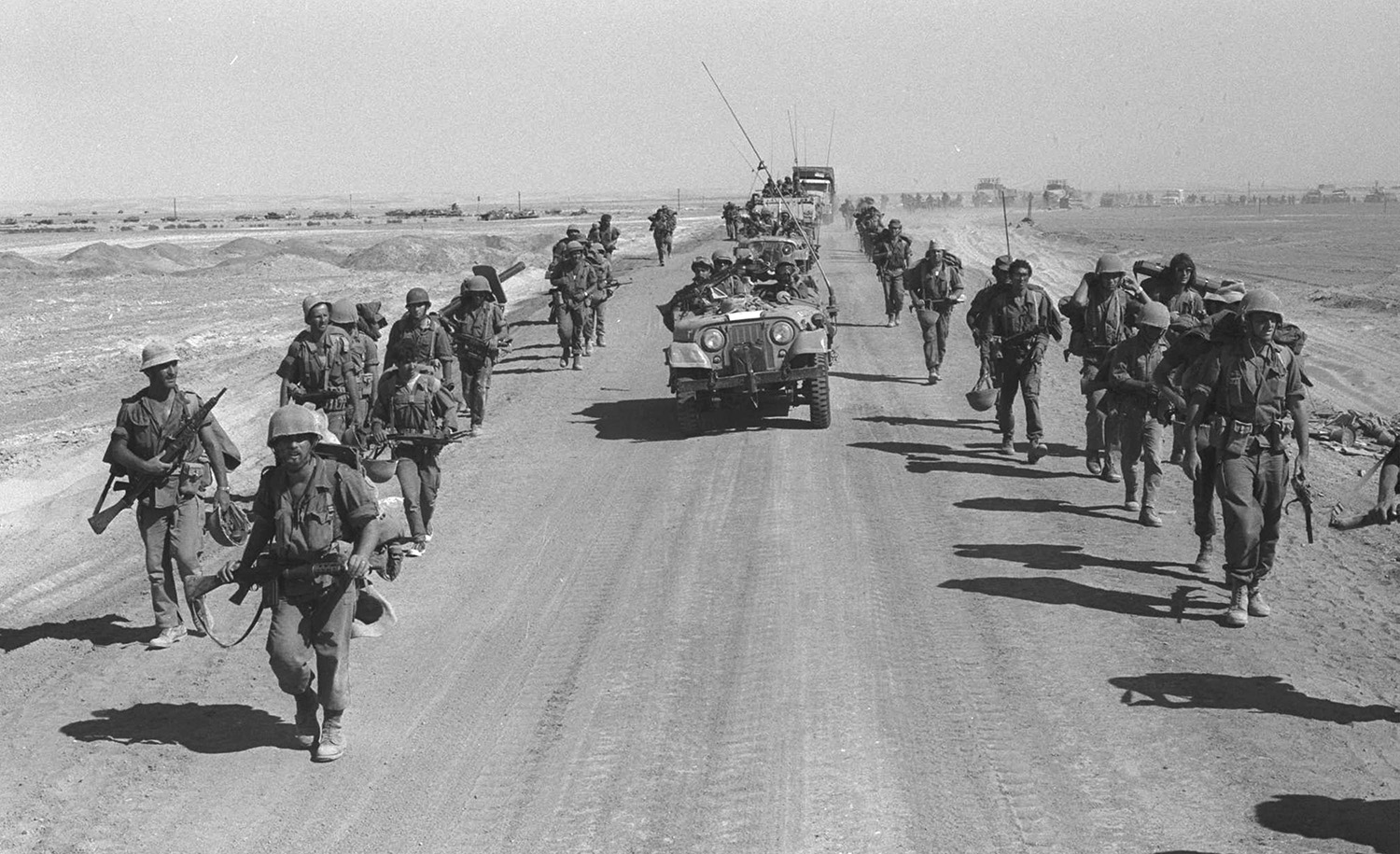

This year’s 50th anniversary of the Yom Kippur War, whose Gregorian calendar date is October 6, has led to a predictable spate of articles, lectures, TV documentaries, and even (assuming that the release of Golda was timed with it in mind) Hollywood films. And yet in Israel, if truth be told, every Yom Kippur in the last 50 years has taken place in the somber light of the 1973 war, the trauma of which has faded only partially with time. Although many who lost sons, husbands, fathers, and friends in the fighting are themselves no longer alive, the memory of it lives painfully on in Israeli society. The fact that it ended in a decisive miliary victory has never compensated in the nation’s consciousness for the price paid for the overconfidence and lack of caution that made possible the near-catastrophic surprise Egyptian-Syrian attack with which the war began.

One of the minor testimonies to the war’s impact is that for a long time now, the words yom kippur shel, “the Yom Kippur of,” have referred in Israeli speech to any debacle that might have been prevented by better judgment and a more modest sense of one’s capabilities. “This is the Yom Kippur of the Ministry of Finance,” a ministry official was quoted as saying in 2000 about a costly government surrender to striking port workers in what is the earliest documented use of the expression that I have been able to find, although it undoubtedly goes back much further. And December 10, 2013 is still known in Israel as “the Yom Kippur of the weathermen” because predictions of moderate rainfall on that day failed to foresee the unusually heavy snowstorm that hit the country, especially Jerusalem—which, caught unawares, was paralyzed for days.

Two years later, when Benjamin Netanyahu beat Isaac Herzog handily in the national elections of 2015 despite forecasts of a close race, a news service ran the headline, “The Yom Kippur of the Pollsters.” And “The Yom Kippur of the [Agricultural] Authorities” was a similar headline in 2022, when an estimated 100,000 chickens were killed by an outbreak of avian flu that no one had seen coming.

The “Yom Kippur of” usage has been applied to more trivial events, too. “The Yom Kippur of the Ramat Gan School Bus System” was how a transportation breakdown in a municipal suburb of Tel Aviv was referred to by a 2022 press report. And earlier this year a columnist poked fun at such hyperbolic abuses of the expression by saying of a televised Knesset debate in which the opposition parliamentarian Gideon Sa’ar, known for his poker face, was seen winking slyly at a colleague, “It was the Yom Kippur of the body-language specialists.”

All this has produced an anti-“Yom Kippur of” reaction. “As if one can compare a national trauma with its over 2,000 dead and devastated generation to other debacles, however severe!” recently wrote a Hebrew blogger calling himself Matsav Ruaḥ, or “Moody.” He went on:

The Hebrew language is full of expressions related to Jewish holidays and tradition. When we say that someone “looks like Tisha b’Av,” or that “every day can’t be Purim,” we are being true to the spirit of such days, even if in a secular context. . . . But Yom Kippur is the furthest thing possible from a debacle caused by taking things too lightly. It’s a day for deep probing and readiness, a true opportunity for self-correction in the understanding that it is never too late for genuine repentance. As far as I’m concerned, yom kippur shel is the Yom Kippur of the Hebrew language. (Just look at who is using the expression now!)

This is well and wittily put, but I’m not sure I agree. It’s certainly true that if Israel’s generals and politicians had more deeply probed their assumptions and decisions in the hours, days, months, and years preceding October 6, 1973, the war would probably not have broken out—and that if it had, it would have found Israel fully prepared. Precisely the fact that a smug sense of invincibility left the country unprepared, so that that the frightful losses it suffered were in no small measure its own fault, constituted much of the war’s trauma.

But is this not true of Yom Kippur in Jewish tradition, too? Is it not supposed to be a day of judgment on which many are judged harshly because they do not take it seriously enough? Not everyone is like Moody. There is no lack of “Yom Kippur Jews” for whom the day means, if anything at all, going through the motions of soul-searching perfunctorily. If the God of Israel chooses to punish them for their unrepented sins in the year that follows, will they not also have had a yom kippur shel?

There has always seemed to me to be a remarkable fit between the Yom Kippur of the prayer book and the Yom Kippur of the 1973 war. In the consciousness of some the two are joined, while in that of others they are not, but in the latter case, too, there is a complementarity. Both are days for reflection on bitter mistakes that have been made, on the dreadful consequences that they have had or could have had, and on the imperative of not making them again; both are days of awe that we have been mercifully allowed a second chance. If what happened 50 years ago causes religious and secular Israelis alike to feel so many of the same things on the same day, why object to popular language’s expressing this?

More about: Arts & Culture, Hebrew, Yom Kippur