Got a question for Philologos? Ask him directly at [email protected].

Although one generally writes biographies of people, not of languages, the Iowa-born Hebrew University professor David Shulman chose to call his recently published book on the Tamil language Tamil: A Biography. Shulman, a world-renowned scholar of the Dravidian language family of southern India to which Tamil belongs, did so, as he says in the book’s preface, because “Everywhere one looks at language, at every point we touch it, we see movement, aliveness, and singular forms of self-expression.” Tamil: A Biography is the rare work by a professional linguist that is about a language’s personality, not just its formal mechanisms. Shulman is a lover of Tamil, and like a lover he expects us to be as fascinated by every aspect of his beloved as he is. But if one can manage to wade through a superabundance of detail (does one really have to know every shade of lipstick and shape of hairpin ever worn by a woman loved by an author?), there is much that is fascinating in what he has written.

One of the minor details about Tamil that caught my attention in Shulman’s book is the claim that it contributed at least one word to the Hebrew Bible. This is tukiyim, “peacocks,” which occurs in the first book of Kings. In Chapters 9 and 10 of 1Kings we read of an ambitious maritime enterprise conducted by King Solomon in partnership with Hiram, the Phoenician king of Tyre. In 9:26 we are told (as usual, I quote from the King James Version):

And King Solomon made a navy of ships in Etsyon-Gever, which is beside Eloth on the shore of the Red Sea. . . . And Hiram sent in the navy his servants, shipmen that had knowledge of the sea, with the servants of Solomon.

Verse 10:11 then relates:

And the navy of Hiram, which brought gold from Ophir, brought in from Ophir a great plenty of almug trees and precious stones.

And in 10:22 we read:

For the king [Solomon] had at sea a navy of Tharshish with the navy of Hiram. Once in three years came the navy of Tharshish, bringing gold, and silver, ivory, and apes, and peacocks.

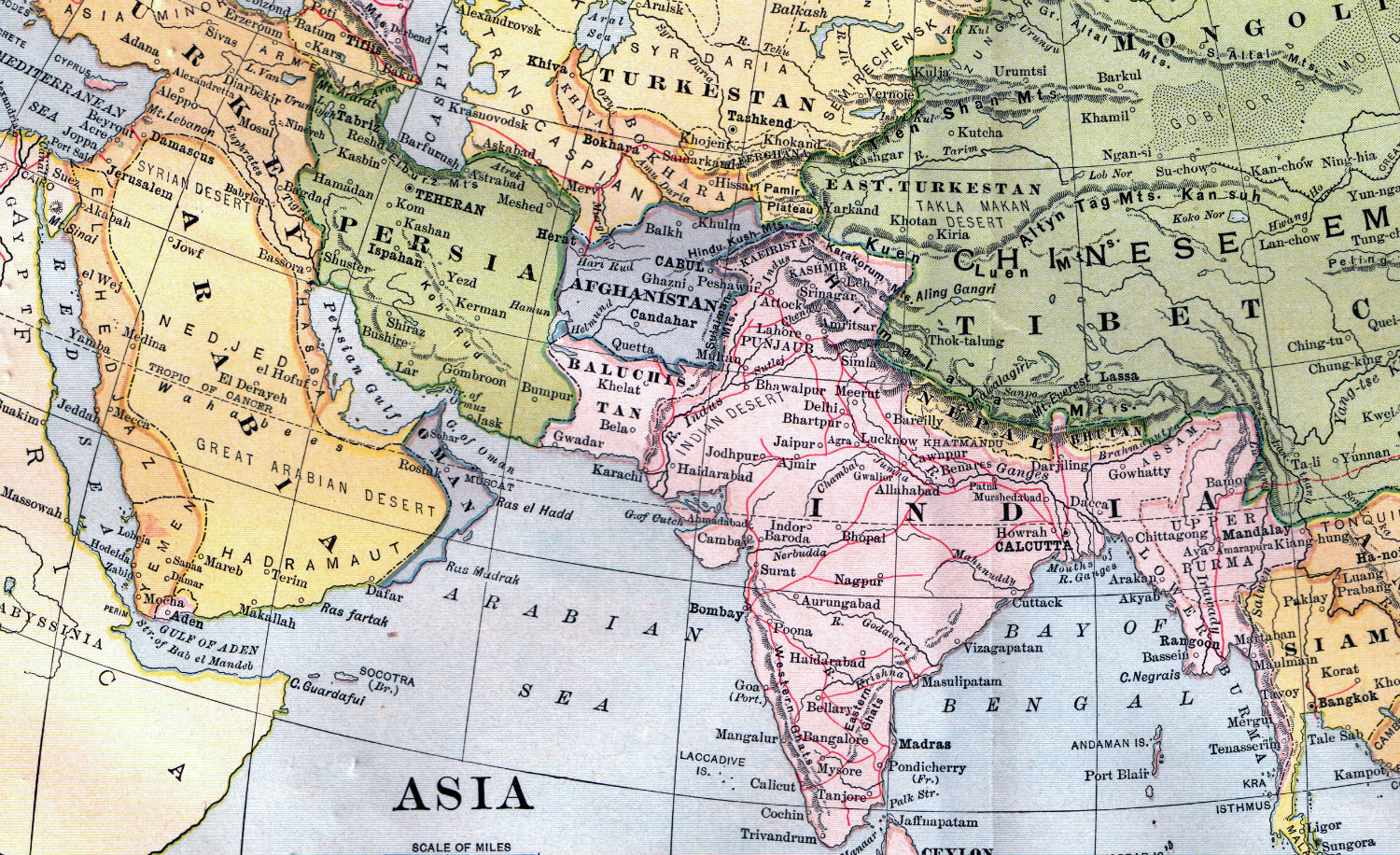

Parts of this are clear enough. Solomon, then in a process of imperial expansion, needed Hiram’s help for a Red Sea fleet because the Phoenicians were master sailors whereas the Israelites of the hill country of Palestine were landlubbers; and Eloth, near which Solomon built his port of Etsyon-Gever, was, like the Israeli city of Eilat that bears its name, at the head of the Gulf of Aqaba at the Red Sea’s northern tip.

Other things are less clear. What are “almug trees”? Where was Ophir? Was Tharshish (or Tarshish, as it is more often spelled in English) a place, too, or was it a type of ship? And what does the Bible mean by “the navy of Tarshish” coming “once in three years”? To where and from where did it come, and why at such intervals?

Were Ophir, and perhaps Tarshish, ports in India? Shulman, following in the path of 19th-century scholars before him, identifies three Indian loan words in 1Kings. Two he traces to Sanskrit, the Indo-European language of northern India that is historically unrelated to Dravidian tongues like Tamil, though the two families greatly influenced each other. The biblical word for ivory, shenhav, he observes, is most likely a compound of Hebrew shen, tooth, and Sanskrit ibha, elephant, while Hebrew kofim, apes or monkeys, “certainly derived from Sanskrit kapi.”

As for tuki (the singular of tukiyim), it, according to Shulman, was “taken from Tamil tokai, the male peacock’s tail.” One can easily imagine, he writes, “ancient Israelite mariners pointing to the [peacock’s] splendid tail feathers and asking their Tamil-speaking colleagues what name it had.” The Tamil speakers would have taken the question to refer to the tail alone; their Hebrew-speaking questioners would have understood their answer to refer to the entire bird.

All of this depends, of course, on the assumption that Ophir or Tarshish, or both, were locations in either India or along the south Arabian coast, the latter of whose ports traded extensively with India and at one of which Israelite sailors might have met their Tamil or Sanskrit-speaking counterparts. (The book of Genesis, in its genealogical account of the races of man, connects an ancestral Ophir with southern Arabia.)

And yet, while the possible whereabouts of Ophir and Tarshish have been much debated, no theory has been conclusive. Some discussants have placed them on the east coast of Africa, where gold, silver, ivory, monkeys, and peacocks could also have been acquired. In that case, one would have to search for the etymons of shenhav, kofim, and tukiyim in the languages of that area—and for the etymon of the almug of “almug trees,” too, which has been somewhat dubiously linked by scholars to Sanskrit valduka, the sandalwood tree.

We seem to be trapped, indeed, in a form of circular reasoning. On the one hand, a number of biblical words are said to have originated in India because Solomon’s sailors reached it or the route to it. On the other hand, Solomon’s sailors are said to have reached India or the route to it because a number of Indian words occur in the Bible!

Is there a way out of this loop? If there is, it is connected to the “once in three years” (aḥat l’shalosh shanim) of 1Kings 10:22. Although nothing I’ve read on the subject treats of this phrase (it’s quite possible that I’m ignorant of scholarship that does), it seems reasonable to assume that it refers to a period of time in which Solomon’s ships regularly departed from Etsyon-Gever and returned to it. Where could they have been in this period?

We know that a half-year shipping cycle existed in ancient and medieval times between south Arabian ports and the west coast of India. Ships would set sail across the roughly 1,200 miles of the Indian Ocean separating the two land masses in spring, when the first, mild southwesterly monsoon winds began to blow toward the Indian coast, and return in autumn, when the prevailing winds began to blow in the opposite direction. The preferred sailing seasons were April-May and October-November, before or after the summer’s dangerously stormy monsoon months and the high seas of winter.

But what could have taken Solomon’s ships three years? Had they simply sailed down the Red Sea from Etsyon-Gever to the south Arabian coast and back, they could have done it in a half-year: embarking in April-May, before the summer northerlies in the Red Sea’s northern half and the summer southerlies in its southern half grew too strong, and heading back in October-November when there was once again an interim of weaker winds. An additional voyage from southern Arabia down the coast of East Africa and back might have been completed in another half-year—southward with the northeasterly trade winds that blow in that region from December to mid-March and northward with the southerlies that blow from April to mid-September. All in all, the ships could have been back in Etsyon-Gever in a year-and-a-half.

Suppose, though, that Solomon’s ships had continued from the south Arabian coast to India. In that case, their itinerary might have looked like this:

April-May of Year 1: from Etsyon-Gever to the south Arabian coast. There, while unloading and taking on cargo, the ships would have waited an entire year to let the squallish summer monsoons and the autumn and winter northeasterlies pass.

April-May of Year 2: from south Arabian coast to the west coast of India. At this point there would have been a half-year’s wait while gold, silver, ivory, precious stones, monkeys, peacocks, and a large quantity of almug trees were being stowed aboard.

October-November of Year 2: from west coast of India back to south Arabian coast, in whose ports the winter would be waited out.

April-May of Year 3: from south Arabian coast back to Etsyon-Gever.

The round trip would thus have taken two full years. Why then does the Bible say that Solomon’s fleet returned “once every three years?” Because, I would propose, this means “every third year,” that is, every spring of Year 3. If that is so, it is indeed likely that an Israelite sailor pointed to a peacock’s tail in a Tamil-speaking Indian port, was told that it was a tokai, and brought the misunderstood word back with him as a gift for Hebrew.

That the word was misunderstood again in the early 19th century by the Haskalah writer Shimshon Bloch in his influential geographical work Shviley Olam, “Paths of the World”—where it was taken to mean “parrot,” which is consequently what it means today in modern Hebrew—this, as they say, is another story.

Got a question for Philologos? Ask him directly at [email protected].

More about: Hebrew Bible, History & Ideas, India, Language, Tamil