The Jews have long occupied a unique place within Western civilization—simultaneously at the center and at the margins. The West—including the rise of European Christendom and the birth of America—was decisively shaped by Hebraic understandings: the revelation that our existence was initiated by a single divine Creator; that human beings were created as God’s beloved partners; that human life is sacred and child sacrifice abhorrent; that human kings are answerable to an ultimate Judge; that human sexuality should be governed by laws of holiness; that rearing children is life’s greatest blessing and God’s primordial commandment; and that despite the painful realities of mortal life, the human story is not tragic but redemptive. Against the pagan belief that fate matters more than freedom, the Jews offered a crucial corrective: the recognition that human beings make history, and that history is a divine drama conceived by God and shaped by men and women as the only covenantal actors in the cosmos. That covenant began when God summoned Abraham to create a new way of life. And since then, we have lived in an Abrahamic world.

While Hebraic understandings shaped Western civilization as we know it, the Jews themselves often lived in exile: not only from their home in the land of Israel, but also from the very Western culture that Israelite teachings helped to create. While Jewish texts like David’s Psalms became sacred scripture, the Jews themselves were often persecuted rather than honored, blamed rather than esteemed, poor rather than princely. They often lived in shtetls and never built great cathedrals. They were the targets of rigged and hostile “disputations” and generally banned from attending universities where they could engage in true dialogue. In their realist genius, the rabbis focused their cultural energy on preserving their own sacred inheritance from an often-hostile world rather than sharing this divine vision with the untutored nations. In one of history’s great (and often cruel) ironies, Christianity would spread the core Jewish message of a covenantal God to the world, often while subjecting Jews themselves to humiliation and worse.

Yet throughout Western history, the greatest Jewish thinkers and leaders—Philo and Saadia Gaon, Maimonides and Abarbanel, Samson Raphael Hirsch and Esriel Hildesheimer—always recognized the importance of Western ideas for expanding the Jewish imagination. Even when the world spurned the Jews, the wisest Jews knew that they needed to make sense of their distinctive place in the West. In modern times, it is no accident that the visionary statesmen and thinkers who led the Zionist renaissance in Israel—men like Theodor Herzl, Abraham Isaac Kook, Vladimir Jabotinsky, and David Ben-Gurion—were deeply educated in the political and moral history of the West. It is no accident that the rabbis and teachers who led the religious revival in the American Diaspora—individuals such as Menachem Mendel Schneerson, Joseph B. Soloveitchik, and Abraham Joshua Heschel—were steeped in the great thinkers of the Western tradition, both ancient and modern. They believed that the Jews needed to understand Western culture—both its greatness and its dangers—in order to fulfill our true mission as “a kingdom of priests and a holy nation” within history.

The spirit and purpose of Jewish education will always reflect how Jews see their place in human history. If Jews and Judaism are insignificant—a parochial people with peculiar rituals and outdated ideas—then Jewish learning will sadly wither from disinterest. If Jewish survival is at stake—as in the early days of the modern Zionist movement—young Jews will rightly train first as farmers, workers, and soldiers. If Jews are proud but permanent outsiders—political and spiritual exiles from a corrupt world that rejects them—then Jewish schools will aim primarily to shield young Jews from the heresies of non-Jewish culture in the name of preserving our transcendent Jewish way of life from generation to generation. Yet if Jews and Judaism are truly summoned to be “a light unto the nations”—a moral and metaphysical Menorah to the world—then the purpose of Jewish education is to kindle that light.

Sadly, we are living in an age of mass civilizational confusion, both in the Western world in general and among the Jews themselves. Unmoored from the best of our past as a guide to our future, modern man is looking for new golden calves to save us: fentanyl, TikTok, pansexuality. The Jewish mission in the world is to help steer us off this nihilistic path: to offer Hebraic remedies for our worst cultural disorders. And that Jewish light depends on educating committed Jews who understand and care about their exceptional role in history, who bring Jewish wisdom into the civilizational arena, and who incorporate the best of Western culture into Jewish life. This is the mission of Jewish classical education: to build a movement of civilizational renewal that looks to the past heights of human excellence as a guide to the future, and that does so with a Jewish mind and Jewish heart.

I. A Short Jewish History of the West

To develop this distinctively Jewish vision of classical education, we need to understand the Jewish meaning of the West, including the modes of education that have long shaped Western culture. The Western ideal of an educated person began with the Greeks, who were the first civilization to understand man as a rational being in search of himself and his place in the natural cosmos. Many cultures and civilizations pre-dated the Greeks: the Chinese, the Mesopotamians, the Egyptians. But Greek culture was the only culture open to culture: the only culture that questioned its own superiority through the application of human reason and that sought to make sense of reality through logic and analysis, even to the point of thinking about the very nature of thought itself and seeking out demonstrable proofs whenever possible.

This Greek quest for truth produced just about every discipline of knowledge that we hold dear: History was invented by Herodotus and Thucydides as an effort to inquire into man’s nature by learning from how he has lived in the past. Greek literature invented the forms of tragedy and comedy to make sense of the human struggle against cosmic forces that seem beyond our control. Greek art sought to depict the nature of man through the image of his body and face. The Greeks invented the study of politics to explain how to live well in an ordered society, and Greek inquiries into ethics were the most sophisticated (if not always the most ethical) that the world had ever seen. In mathematics, the Greeks developed advanced proofs aimed at illuminating the true nature of reality, and in astronomy they used calculations to advance far beyond the discoveries of other cultures that relied on observation alone. The master discipline was Greek philosophy, which applied human reason and dialectic to the fundamental questions of existence.

In the 4th century BCE, Greek philosophers laid out a system for becoming an educated person that would shape Western education for well over two millennia. Aristotle’s disciples retrieved from his thought a pedagogical model that would eventually become known as the trivium, focused on the rigorous mastery of (i) grammar, (ii) logic, and (iii) rhetoric. Grammar was the study of reading and writing in a broad and comprehensive sense, including both the foundations of language and the memorization of the core knowledge essential for thought. Logic involved formal training in how to prove truths and disprove falsehoods. Rhetoric was the art of persuasion, which taught students how to convey truths in the most effective manner possible. This trivium was to be followed by the quadrivium—the four-fold study of nature itself, through the fields of arithmetic, geometry, music, and astronomy.

When the Romans conquered Greece, they adopted Greek models of education and culture as their own, and Latin eventually came to supplant Greek as the primary language of Western culture. Intellectually, the Romans refined and improved Greek disciplines, especially the arts of rhetoric. Morally, the Romans celebrated civic virtue and loyalty to higher causes over the pursuit of personal cultivation and individual excellence. They also elevated the importance of history: where the Greeks saw a series of events fated by nature (including human nature), the Romans focused on man’s role in shaping a national destiny ordained by the gods.

Yet Roman cruelty, decadence, and depravity co-existed with Roman virtue; and for all their combined achievements, Greco-Roman culture remained pagan in this profound sense: man was never elevated to being God’s covenantal partner in redeeming creation; and God was never understood as an all-powerful Creator who nevertheless cared for (and needed) men and women to fulfill His divine purposes, the way a parent needs a child to carry forward his sacred inheritance. While the Greeks and Romans invented sophisticated arts of knowing reality, it was the Israelite “kingdom of priests” that understood the deeper meaning of existence.

At different points, the Jews clashed in war with both the Greeks and the Romans, seeking to preserve Jewish independence in the face of these far more powerful empires. The Romans eventually won on the battlefield, destroying the Israelite Temple and sending the Jews into centuries of exile. But the Israelite view of man ultimately won the deeper cultural battle. For it was the rise of Christianity—a Hebraic transformation of Greco-Roman culture that shaped the West as we know it—that emerged victorious. While the Romans may have sacked Jerusalem, the dim lamp of Diogenes was transfigured by the shining light of the Menorah.

The early Christians were originally members of a breakaway Jewish sect who eventually created a separate religion of mostly gentiles. Persecuted by pagan Rome, they were determined to preach a new version of Judaism, taking Judaism’s most essential idea—the existence of a covenant between God and man, with man as the center of meaning in Creation—to a universal audience. In the Christian view, the covenantal God of the Hebrew Bible was linked to humanity through one special Jew: Jesus of Nazareth. The Jewish idea that human beings were responsible for—and answerable to—God’s manifestation in history was now transformed and promoted in a new gospel.

Over time, the Christians converted Rome and transformed its peoples. Against the cult of the Colosseum, they insisted on the biblical notion of the dignity of the human person as created in the image of a caring God. Against fatalism, they taught that man bore enormous responsibility to care for and cultivate creation itself. Against the lonely feeling that man was merely another creature in the cosmos or another plaything in the hands of Olympian gods, they taught the world that human history has a redemptive purpose. Christianity transformed the greatest pagan accomplishments into God-seeking triumphs of the human spirit—as seen in the creative genius of Christian civilization in art, architecture, literature, and music.

And yet, despite Christianity’s transformation of Greco-Roman culture through a Jewish lens, Christendom could be profoundly cruel to its Jewish progenitors. The Jews themselves were often treated as a human sacrifice in the quest to spread the Israelite vision to the world. To be a Jew, the early Christians believed, was to deny the salvation offered by God’s sacrifice on the cross, clinging to a covenantal promise and a separate “Old Testament” way of life that the new revelation of the cross had superseded. There were times and places in Christian history in which Jews lived well with Christians, even on friendly or at least tolerant terms. But the Jewish position in Christendom was usually precarious at best and subject to violent subjugation at worst.

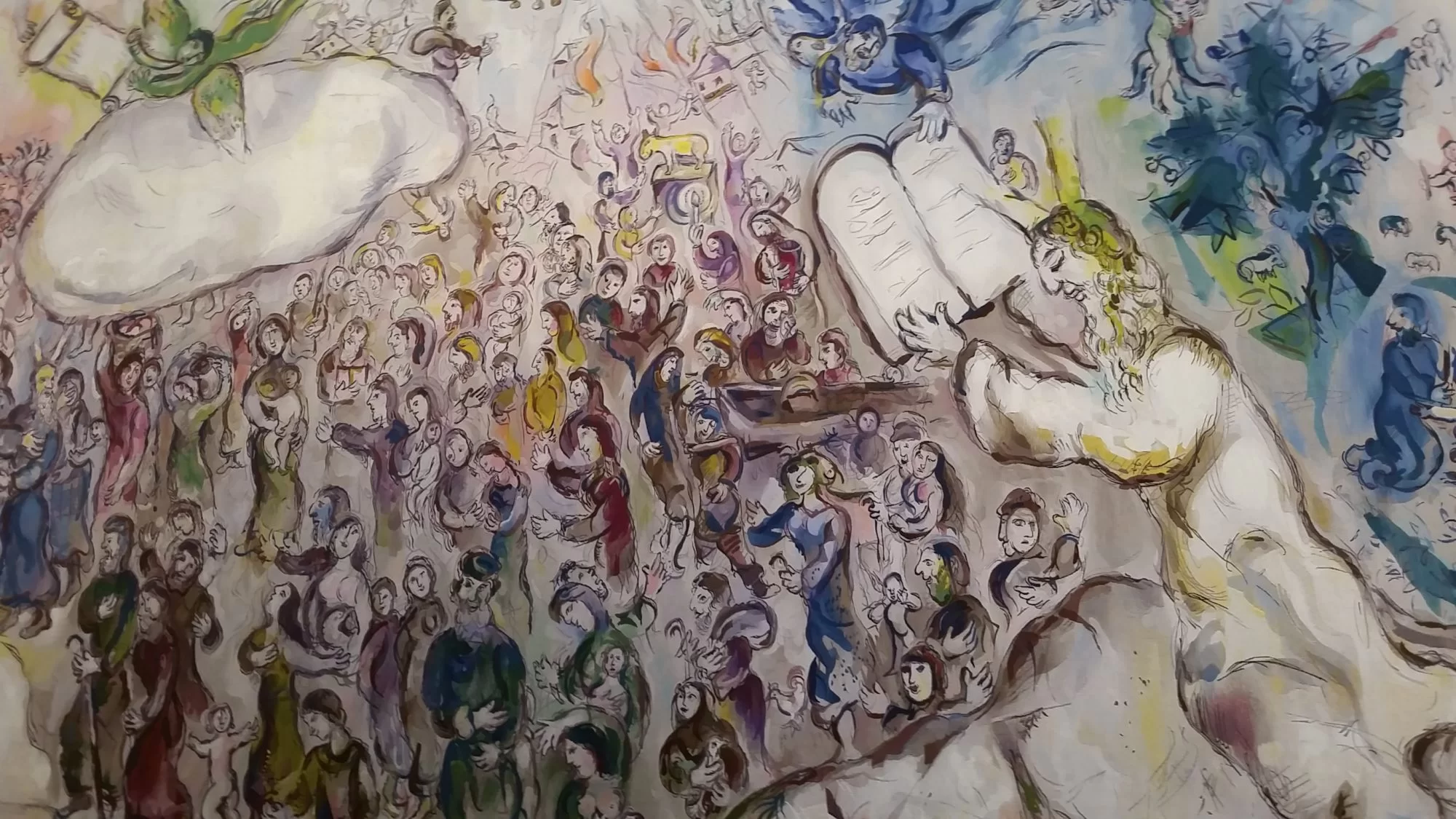

Here lies the tragic irony at the heart of the West: the rise of Christianity was a victory for Jewish understandings against godless paganism and yet a new source of oppression for the Jewish people themselves. This explains why the Jews have long harbored a deep cultural ambivalence—and often a deep antipathy—toward the very Western culture that brought Jewish understandings to the world. What pleasure or pride could the Jews take in Michelangelo’s paintings of biblical images amid the poverty, persecution, and inquisitions?

Understandably, many Jews—including many learned and pious ones—came to resent and reject the very Western culture that they were responsible for helping to create. Many other Jews came to resent the disadvantages and apparent parochialism of being Jewish as an impediment to joining the high (Christian) culture of the West. They rejected—or tried to reject—their own Jewish identities. The Jew thus faced two powerful temptations: abandoning his own Jewish heritage or belittling the undeniable achievements of Western civilization. Amid the struggle for Jewish survival, both pathways were understandable. Yet they were not the only Jewish answers to the perennial Jewish question. The greatest Jewish thinkers and educators of the past charted a different path: not assimilation, not isolation, but a true Jewish encounter with the West.

II. The Roots of Jewish Classical Education

In their confrontation with Christian civilization and eventually with the post-Enlightenment world, the architects of Jewish learning sought to pursue three goals at once. They developed a unique Jewish approach to education.

The first purpose of Jewish education was Jewish resistance against assimilation: resistance to paganism, resistance to the high pagan culture of Greece and Rome, resistance to embracing Christianity as the potential ticket (in Heinrich Heine’s famous phrasing) to the intellectual, cultural, and economic riches of the Christian world. The rabbinic system thus focused on the inculcation of Jewish law, the mastery of Jewish ritual, and the observance of the Jewish calendar. Learning Talmud became the highest possible intellectual pursuit. This allowed Jews—even in poverty and exile—to understand themselves as aristocrats of mind and spirit. It also allowed the Jews to continue their role as sacrificial partners with a covenantal God—embodied in the physical acts of Jewish ritual life—despite outside insistence that such practices were peculiar, parochial, and unnecessary.

The second purpose of Jewish education was integration of the discoveries, insights, and achievements of Greco-Roman (and eventually Christian) culture in a uniquely Jewish way. Jews could not ignore Western achievements in natural science, medicine, architecture, art, literature, and political economy. These novel human accomplishments and insights thus needed to be incorporated—both practically and theoretically—into the Jewish vision of life.

The third purpose of Jewish education was to make a uniquely Jewish contribution to the West itself: to see the Israelites as a moral and metaphysical light to the nations, whose core ideas might influence the ultimate direction and meaning of the Western story and thus the human story. This includes offering Hebraic remedies for Greco-Roman disorders; and providing “Old Testament” wisdom when the Christian (or post-Christian) world goes astray.

Holding these three purposes together was—and remains—no easy challenge, and the relative urgency and weight of each distinct purpose necessarily changed from age to age and place to place. Yet the ideal form of Jewish education—past, present, and future—aimed to advance all three purposes at once: resisting anti-Jewish ideas in the name of Judaism, integrating the best of Western developments into the Jewish way of life, and contributing Jewish wisdom to Western culture. This was—and remains—the guiding spirit of Jewish classical education.

This effort at a grand Jewish synthesis took full shape in the medieval period. In the 12th century Islamic world, Maimonides confronted Greek and Muslim thought from all three angles: codifying Jewish law as a form of resistance to non-Jewish culture, integrating Islamic and Greek philosophy into Jewish thought, and contributing to the broader culture by bringing together the rational truths of Greek philosophy and the revealed truths of the Hebrew Bible. The Maimonidean mode of thinking clearly had a great influence not only on Sephardic and Mizrahi Jews of the Islamic world but on figures such as Thomas Aquinas, the most influential mind in medieval Christendom, who called him “Rabbi Moses.” This Maimonidean-Thomistic paradigm would become the standard for both Christian and Jewish classical education moving forward.

During the Renaissance, Italy’s Jewish communities—which included Italian, Sephardic, Ashkenazic, and French Jews—embraced these medieval classical models as their own. Isaac Abarbanel—the renowned rabbi, philosopher, and statesman—was steeped in Seneca. Ovadia Sforno, a well-known Italian Renaissance era rabbi, was highly proficient in Latin and studied Aristotelian philosophy. David Provenzale opened a new Jewish school that provided both Jewish and classical instruction, preparing Jews for admission to the best Italian universities while remaining in a thick Jewish cultural environment. The rabbi David ben Judah Messer Leon’s writings on the trivium were commonly studied by Jews throughout Italy. The Jewish-classical curriculum emphasized medicine, history, poetry, and moral philosophy. Students learned both Latin and Italian composition; they read great works ranging from Aristotle’s Rhetoric and Poetics to Cicero’s oratory and Dante’s epic poems. The focus on musicality and language led to a flourishing of Hebrew writing, especially Hebrew poetry. Jewish culture in Italy arguably surpassed even the achievements of Andalusia (medieval Muslim Spain) in the sheer output and quality of its poetry. A great Jewish scholar would be known as a hakham kolel—a semi-translation into Hebrew of the Latin homo universalis. This classical mode of education was combined with traditional instruction in biblical texts, Hebrew grammar, and the Talmud. The aim was to form a uniquely Jewish version of the Renaissance man.

In the 17th century, the Dutch Jewish community embraced a similar educational approach. Schoolchildren were taught to write poetry in meter. Traditional Jewish studies were supplemented by a curriculum that offered instruction in up to six languages. Classes were mostly conducted in Portuguese, since these Jews were mostly Spanish and Portuguese conversos who fled to the Netherlands. Hebrew was taught in both written and spoken forms; Latin was used for classical studies; and Spanish was used for the mastery of modern literature. Many students also learned Dutch or French, and the most promising students also studied advanced theology, philosophy, and rhetoric. This Jewish educational renaissance produced a wave of Jewish book-printing, and both ancient classical and Renaissance-era texts were studied by Dutch rabbis. Rabbi Isaac Aboab de Fonseca possessed works from nearly every major classical author, as well as works by early modern writers such as Bodin, de Vega, Machiavelli, Montaigne, and Hobbes. This immersion in Western learning was combined with the inculcation of a traditional religious ethos among Portuguese-Dutch Jewry. The exemplars of this movement rejected the newer philosophical trends that sought to overthrow the authority of traditional religion; and the conversos—Jews who had long hidden their identity and pretended to be Christian—re-Judaized and (with some notable exceptions) maintained a strong religious identity for generations.

The most significant modern example of Jewish classical education in recent times emerged in the Orthodox communities of 19th century Germany, led by the rabbis Samson Raphael Hirsch and Esriel Hildesheimer. Born in 1808, Hirsch received a classical education at the Hamburg Gymnasium and then at the University of Bonn. He was proficient in English and read Latin. At Bonn, he studied Juvenal, Leibnitz, Kant, philology, and the natural sciences, while also becoming well-versed in the writings of Cicero, Tasso, and Shakespeare. He defended poetry against its rabbinic detractors, insisting that ancient and difficult-to-read poems help Jews appreciate the power of language to shape the human spirit. He believed that the only way to resist the cultural assault on traditional Judaism was to educate traditional Jews with a deep appreciation of high culture. As he declared: “The only thing that can save us is a true union of religious knowledge and religious life with a proper secular education. This is the intimate, whole-hearted union of Torah im Derech-Eretz [Torah alongside the way of the land] as it was taught and bequeathed to us by our great ancestors.”

In 1851, Hirsch became the rabbi of Frankfurt-on-Main, where he began establishing schools with a dual Jewish-Western curriculum. He did not seek to produce theologians or intellectuals like himself, but simply to ensure that members of his community could perpetuate lives and communities imbued with Jewish culture and shaped by cultured Jews. Even with this limited end in mind, his students needed to learn four languages: German, French, English, and Hebrew. In addition to math and science—worldly subjects with direct practical applications—they studied history, geography, writing, music, and art. They also immersed themselves in the sophisticated literature of the day—such as the novels of Karl Gutzkow, as well as the poetry and dramas of Racine, Goethe, Schiller, Herder, and Lessing—and attempted to integrate them with Jewish ideas. Science and history were grounded in a Jewish perspective, and literature with Jewish themes and characters was prioritized. Hirsch taught students to see Schiller’s poetry as imbued with Hebraic idealism; and one school went so far as to call an assembly to recite a public blessing of thanksgiving for Schiller on his 50th birthday. Rabbi Mendel Hirsch, Samson Raphael’s son and successor, likewise urged students to understand the dramas of Racine as inspired by the Bible.

While embracing the significance of learning from and understanding the best of Western culture, the elder Hirsch showed no hesitation in rejecting non-Jewish ideas that he saw as antithetical to Judaism. He always judged the West by Jewish standards, while also believing that Jews could learn from and admire the peaks of non-Jewish culture. His goal was to sift through the most consequential works of Western culture, helping students to appreciate the Jewish roots in many of them and to process the rest from a uniquely Jewish perspective. His aim was to resurrect Jewish involvement in the broader Western story, involvement that had suffered from centuries of persecution, poverty, and exclusion from the great universities of the Christian West. He stood against both those rabbis who wrongly dismissed, belittled, or ignored Western culture and against the supposedly “cultured” Jews who wrongly dismissed, belittled, or ignored Torah learning and Torah life.

Hirsch was not alone. In 1851, Rabbi Esriel Hildesheimer established a classically oriented parochial school for children and a classically oriented rabbinical school in Hungary. In addition to traditional Judaic studies, these schools taught Latin, Greek, German, Hungarian, geography, history, and mathematics. The students were assigned writings by Homer, Cicero, Virgil, Josephus, and Gesenius. In their spare time, students were encouraged to practice spoken Hebrew. In 1873, Hildesheimer established an even larger rabbinical school in Berlin. He believed that only classically educated rabbis—who understood Western culture from Jewish heights and in a Jewish spirit—could answer the two great intellectual challenges of that era: namely, the challenge posed by the secularizing European academic world, which sought to belittle all religion as old-fashioned superstition; and the challenge posed by the German Reform movement, which aimed to shed many of Judaism’s particular practices and traits in the name of progress.

Hirsch and Hildesheimer built a larger movement, and classically oriented Orthodox Jewish schools spread all over Germany: in Burgpreppach, Cologne, Frankfurt, Fulda, Furth, Halberstadt, Hamburg, Hesse, Hochberg, Mainz, Nuremberg, Schwabach, and Wurzburg. In Berlin, the Adass Jisroel school became the largest religious school in Germany, and gained official recognition from the state as a pre-university gymnasium that could grant Abitur diplomas. This success occurred despite persistent government persecution, including the refusal to allow Jewish schools to devote sufficient hours to Jewish subjects. Challenged from all sides—by Reform Jews who wanted to leave the old Jewish ways behind, by traditional Jews who saw secular learning as dangerous and distracting, and by German overseers who treated Judaism as a fossil religion—Hirsch stood his ground. For he believed that the Jews had a grand purpose within Western civilization:

Put into the world as a reminder of God and of man’s place in history, this people (the Israelites) was to become an instrument for the ultimate gathering of all nations around God and around the Law He gave so that man might properly perform his Divinely-ordained mission in the world . . . . With the legacy of God to all mankind still firmly in its hands, this people was then to be dispersed among the nations as “God’s own seed”. The promise that this people would eventually be delivered was to indicate to the other nations that redemption would ultimately dawn for the rest of mankind as well. In order that this one people might be able to persevere in its march among the nations through centuries of history to come, God appointed men of “keen vision” to interpret for this people the significance of the rise and fall of the other nations and of its own march over the mausoleums of history. These men were also to communicate to their people the promises of God for its future so that this people might walk with confidence amidst the nights of the centuries toward the dawn that awaits it and the rest of mankind.

Here, then, we have a people that emerged from the course of world history, that was placed into the midst of the nations to advance the goals of world history, and that was endowed with historical vision. Should not the sons of such a people understand that historical studies of the development of nations are truly not superfluous, but that they are, in fact, virtually indispensable? Will the sons of the Jewish people even begin to understand that ancient vision . . . if they understand nothing about the influence of the Yaphetic-Hellenistic spirit on the civilization of other nations, an influence that endures to this day?

In other words: the Jew—even when history thrust him to the margins—should take metaphysical and moral responsibility for the West, both because the West needs Jewish correctives to its own civilizational disorders and because the West itself is a worthy (if often wayward) act in the Providential story of mankind. As Hirsch put it: “The more devotedly Judaism, without abandoning its own unique characteristics, weds itself to all that is good and true in Western culture, the better will it be able to perform its uniquely Jewish mission.” This is the spirit of Jewish classical education.

III. The Rise of Progressive Education

While Hirsch and his disciples—against all odds—were creating a Jewish classical education movement in central Europe, a new form of education was taking root in the emerging industrial age, especially in America and Britain: the progressive movement. As the name suggests, the progressive education reformers believed that the past needed to be overcome more than learned from; that the economic and psychological needs of the industrial age required new modes of instruction; and that classical education was outdated, impractical, and too aristocratic for the new democratic era.

Classical education was always geared towards the liberal arts: preparing students for liberty by initiating them into the Western intellectual tradition and immersing them in the “best that has been thought and said,” in the words of Matthew Arnold, the British essayist and architect of 19th-century classical education. Progressive education was much more “practical” in its aims: producing competent workers for the new industrial economy and reliable citizens for the new forms of democracy that were replacing the age of emperors, kings, and high priests. The spirit of individualism and egalitarianism informed this movement, as progressives sought to give students themselves control over their own learning rather than inculcating them in a grand tradition as the foundation for independent thought. Progressive education took many forms, ranging from the anti-phonics activism of Horace Mann to the experiential and democratic education of John Dewey to the student-centered learning inspired by the writings of Jean Piaget. But it is possible to generalize about its key features—and to see the stark divide separating it from the classical model of learning that Samson Raphael Hirsch and Esriel Hildesheimer sought to advance.

First, progressive education opposed memorization and content mastery as a chief goal for young students. Progressives believed that memorization was a waste of time (a prejudice exacerbated greatly in the age of Google). They believed that ready access to key facts, figures, and foundational texts was unnecessary for the establishment of critical thinking. They preferred, instead, to make young children “love to learn,” which meant emphasizing playful activities over disciplined mastery.

Second, progressive education celebrated spontaneous creativity as opposed to the imitation of excellence. Historically, classical education involved training students by understanding and emulating the achievements of the masters, and thereby internalizing the disciplines and standards needed to produce serious cultural expression. Only then, after an apprenticeship in excellence, was it possible for a talented artist or writer to create something new by breaking the old rules and setting out on his own. Progressives believed in skipping ahead: going straight to the unencumbered self.

Third—and ironically—progressive education tended to rely too heavily on memorization in the one area where it is least desirable: mathematics. Rather than teaching mathematical proofs, most progressive math curricula focused on the (much easier) memorization of facts and processes. This robbed students of the ability to think in the field that, along with philosophy, is most important to the development of true critical thought.

Fourth, progressive education dismissed the study of Greek and Latin and diminished the importance of learning multiple languages. Progressive reformers insisted that foreign languages were unnecessary for a comprehensive education, since translations of just about everything were proliferating. Likewise, they argued that learning the Latinate grammar of their own native languages was simply an unnecessary luxury. The idea that there are intellectual and spiritual benefits of being able to think and feel in another culture’s language was set aside in the name of efficiency and utility.

Finally, progressive education replaced an emphasis on reading “great books” with either specialized textbooks or with the contemporary literature of the hour that claimed to be more “relevant.” In the name of democratizing education, they gradually cut students off from their own civilizational roots.

IV. The Hollowing Out of Western Civilization

The great wars of the 20th century—World War I and World War II—put classical education on life support. Amid the high-tech bloodshed, utopian fantasies, and godless tyrannies, the West lost faith in its own civilization rather than looking to the best of the past for the seeds of renewal. The Western world entered a post-Christian era that, as the Russian dissident Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn described in his famous 1978 Harvard commencement address, pitted two hyper-modern philosophies against each other: the individualism of the West and the Soviet communism of the East. The Covenantal relationship between God and man that had long defined the West at its best had degenerated into a form of civilizational schizophrenia: the false optimism that man could create his own worldly utopia without God, and the corresponding despair and destruction when we paid no attention to the Providential script of the Mosaic God. In such a world, studying Greek, Latin, or Hebrew seemed like a misplaced romanticism.

For the Jews, the post-World War II period was an era of normalization and miraculous re-birth. In America, most Jews were still involved in the many decades-old Jewish project of “making it” in American society. They largely attended progressive public schools, supplemented by limited and largely ineffective weekly visits to an afternoon or evening Hebrew school. The grand idea that the Jews were responsible for the West had no place in either the mainstream Jewish or general culture, especially in an era when the gospel of church-state separation meant that the Bible itself had lost its once-important place in teaching Americans about their own Hebraic heritage. And the Jewish day school movement—planting seeds of hope—was still small and nascent. In Israel, a new school system came to life, with Hebrew as the national language and the Bible as part of the core curriculum. This was truly miraculous: a generation of Jews growing up in the land and locutions of their forebears. Yet the Zionist movement was understandably dominated by the practical considerations of founding and developing a Jewish state, including the education of farmers, workers, and soldiers. Cultural Zionism took a back seat, and the self-appointed arbiters of elite Israeli culture—such as the Canaanite movement in the arts—were often focused on trying to create something new and detached from both the exilic traditions of the Jewish past and the high culture of the West that had long ghettoized the Jews. Some Zionist intellectuals sought refuge in Marxist theories and modernist trends. The Bauhaus architecture of Tel Aviv is just one visible product of this mentality: an entire neighborhood disconnected from any tradition or historical heritage. And in Europe, the citadels of Jewish learning were simply gone: the burned down casualties of hatred and war.

In both the Diaspora and the new Jewish state, a heroic group of Jewish educators sought to re-build traditional Jewish culture. Many of them poured their heart and soul into yeshiva education: trying to resurrect, out of the ashes, the spirit of Yavneh—just as ben Zakkai had done after the Roman destruction of the Israelite Temple—by building a school that kept the Jewish flame alive. Yet even the most classically educated rabbis—like Yitzchak Hutner and the Lubavitcher rebbe—placed little emphasis on classical education, believing that the crisis after the Shoah demanded a singular focus on the recovery of Torah Judaism. A few Jewish leaders sought to bring the Jewish classical tradition to new lands: Rabbi Joseph Soloveitchik wanted the Maimonides School in Boston to be a Jewish version of the elite Boston Latin School, just as Rabbi Abraham Isaac Kook had wanted a religious gymnasium to go alongside the two well-known secular gymnasia in the land of Israel. Both, however, were rebuffed by lay leaders who objected that such old-fashioned ideas did not serve the practical needs of the Jewish hour.

Yet in the decades that followed, the Western world soon came to discover what happens when young people have no religious, cultural, or civilizational moorings: the great revolt of the 1960s. The new radicals offered their own anti-Judeo-Christian gospel. In an age of radical egalitarianism, they declared that every cultural idea should be treated as equally valid and nothing held as sacred. In an age of radical individualism, they proclaimed that every person should write his own ethical rules. In an age of tolerance, they demanded that every way of life be accepted and celebrated, except those traditional ways of life rooted in the teachings and traditions of the Bible. The counter-culture—which has now become our mass culture—was a revolt against the remnants of the Hebraic West. The age of mass civilizational ignorance and moral confusion had fully arrived and completed its successful run through our key institutions, especially the universities and then the schools. The progressive revolution in education bore its sour fruit: specialists without spirit, sensualists without God, unencumbered selves adrift without deep roots or higher aspirations than the pursuit of pleasure, distraction, or triviality. And as we have seen in the current era of “wokism,” dissent in the name of tradition is not tolerated.

In response, a brave group of conservatives and classical liberals sounded the civilizational alarm bell—in books like Christopher Lasch’s The Culture of Narcissism, Allan Bloom’s The Closing of the American Mind, and E.D. Hirsch’s Cultural Literacy. They showed what the triumph of relativism meant for education, and they called for a return to a more traditional model of educating the young. And, remarkably, a new movement—the modern classical education movement—was born.

In the mid-1990s, the Society for Classical Learning was established as a network of Christian classical schools in America. It now has 100 schools and growing. The Association of Classical Christian Schools is a network of over 300 schools teaching more than 40,000 students. The Institute for Catholic Liberal Education began in 1999 and now includes 120 schools in its network. Hillsdale College in Michigan produced a new K-12 classical curriculum and launched the Barney Charter School Initiative, which now includes dozens of classical charter schools in 12 states throughout the country. The Great Hearts Academies network educates about 20,000 students each year in Arizona and Texas in over 30 public charter classical schools. A few years ago, it opened an Institute for Classical Education to assist schools and homeschoolers who want to adopt classical education. The Classical Charter Schools network operates four charter schools in the South Bronx that have received awards from the US Department of Education for their success in serving underprivileged children. Memoria Press and the Highlands Latin Academy have produced a particularly outstanding Latin curriculum, helping to revive a subject that was dying. They now oversee a network of schools and disseminate a remarkable K-12 curricula to Christian schools, public charter schools, public school districts, and home-schooling families. The Classical Academic Press, which began in 2001, also services both Christian and non-Christian audiences. There have even been efforts to compete with the SAT and ACT from a classical perspective. The “Classic Learning Test” is now accepted by over 200 colleges and universities.

In parallel, there is a growing movement to educate classical teachers to keep up with this remarkable growth. The University of Dallas’s graduate program in classical education teaches over 100 graduate students per year (and will soon be offering, in partnership with the Lobel Center for Jewish Classical Education, a new Jewish track). Eastern University’s Templeton Honors College offers a Master of Arts in Teaching in Classical Education. St. John’s College, Arizona State University, and Hillsdale College have all been working to establish graduate programs in classical education, along with denominational efforts like Houston Baptist University’s Master of Liberal Arts program, which includes an emphasis on classical learning.

Taken together, this is the most exciting cultural movement in the West: an effort to renew our civilization by returning to its Jewish, Christian, and classical foundations, starting with our youngest children and building forward.

V. The Renaissance of Jewish Classical Education

In America, there is much to be thankful for in the world of Jewish education today—including an expanding Jewish day school movement, myriad summer programs and fellowships aimed at engaging young Jews in recovering their Jewish heritage, and a realization among parents (sharpened during Covid) that progressive education is bad for America but especially bad for the Jews. The time is now for a new Jewish classical education movement, rooted in a few basic principles: the belief that mastering the classical arts of grammar, logic, and rhetoric is essential for every Jewish student; the belief that Jewish ideas lie at the heart of Western civilization and that Western history, literature, and culture are the heritage and responsibility of every Jew; the belief that reading and understanding the canonical texts of Jewish civilization—especially the Hebrew Bible—is indispensable for forming committed and covenantal Jews; the belief that language mastery and fluency—including Hebrew, Latin, Greek, and modern languages—should begin as early as possible; and the belief that America and Israel are two exceptional nations, which every Jew should celebrate, preserve, and strengthen.

So what would a Jewish classical school actually look like?

Preschool, kindergarten, and first grade would be taught almost entirely in Hebrew, accomplishing what many Jewish schools promise but do not actually deliver: early fluency in the language of the Jews. Greek or Latin would be introduced in third grade, followed by an additional spoken language (such as French) one or two grades later. Along the way, students would develop memorization skills, which would be perfected through diligent practice, musical rhythm, and the perception of intellectual connections among related classical works. Students would gain a command over a vast amount of textual and historical knowledge, understood as the gateway to serious thinking, creative imagination, and cultural self-understanding. They would memorize poetry—Jewish, classical, and modern—from a young age. They would immerse themselves in great works—biblical, rabbinic, classical, and modern—as the prerequisite for genuine originality and creativity.

These skills would provide the foundation for understanding Western civilization as Greco-Roman culture re-examined—and corrected—in a Jewish lens. This vision would shape how we teach and understand every discipline of knowledge. For example:

In history: Herodotus and Thucydides invented historical methodology, but it took Augustine—shaped in his vision by the Hebrew Bible—to see history as a humanly-led and divinely-assisted drama, with mankind seeking to break out of the eternal recurrence of the same and achieve real progress. In the Hebraic vision, life within time is not tragic but redemptive, and so the study of history is not a meditation on the fixed nature of things but a creative quest to understand the relationship between past, present, and future.

In literature: the Hebraic vision transformed the Greek tragic view of life into a very different sort of story, one that is both more realistic and more hopeful. Shakespeare’s Hamlet, for instance, may seem like a tragedy, but it broke from the Greek tradition in biblical ways. The plot is driven by choice, not fate. Unlike a Greek play, the story might have ended differently. Human life is a question, not a fait accompli.

In art: medieval iconographers came up with a new art form called “reverse perspective,” in which they focused on God’s perspective on man. And when Renaissance artists returned to classical themes, they saw not fixed natures (as the Greeks did) but the sublimity of an eternal moment. They did not paint and sculpt frozen images of Isaac or Socrates trying to capture the essences of their natures. They painted men in motion—capturing the eternal significance imbued in every moment of human life. By studying the masterworks of Western painting, sculpture, architecture, and music, Jews would come to appreciate aesthetic—and therefore human—greatness.

In political thought: the wisest Greeks objected to tyranny, but only the Jews saw political freedom as the necessary condition for living in accordance with a higher, divine covenant. The Israelite God liberated the people of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob from the pharaohs of Egypt; the true God remembered that human beings were created for freedom rather than doomed to despotism and slavery.

In science: Aristotle thought that the natural state of things was rest. It took Galileo, a Christian influenced by the Hebraic vision of time, to realize that everything is always in motion; and that this reality is not something to fear but an opportunity to achieve new horizons by interrogating nature.

In a Jewish classical school, every field of human inquiry and endeavor would deepen the Jewish understanding of human life as a covenantal relationship between God and man. The curriculum would form Jews who understand that the weight of glory is on their Jewish shoulders. They would come to understand that human beings—the free and improvising thespians of history—can sometimes put God’s Providential purposes in peril, or can help realize those divine purposes in new and creative ways. Man often chooses evil over good, and men often give in to despair rather than preserving hope. But as classically educated Jews, they will come to realize that Pascal’s famous wager had it backwards: God bets on man, and while God’s wager on men and women in history does not always return a winning hand, the eternal Jew endures, giving God-and-man together enough hope to let the story continue. As Mark Twain famously wondered: “All things are mortal but the Jew; all other forces pass, but he remains. What is the secret of his immortality?”

VI. The Menorah Jew

We understand that such ideas—that Jews as a Chosen Nation should take responsibility for the West, that the West itself is worthy of renewal and celebration, and that we must look to the Judeo-Christian past as a guide to the future—cut against the grain of both modern and yeshiva culture.

The Assimilated Jew (or Western Everyman) takes his educational cues from the hyper-modern world as it is. He places limited value on the study of history, literature, religion, and culture except as a means of acquiring useful “critical thinking skills” that he can apply in other domains, such as medicine, finance, marketing, and management. He can reach the highest levels of educational attainment in the modern world—and build a highly successful career—without knowing very much about the history and spirit of Western civilization. He can master STEM without Shakespeare, finance without history, medicine without the Bible, marketing without culture. To the extent that he thinks about culture at all, he believes that modern (or post-modern) culture is more tolerant and therefore superior to the “fundamentalist” orthodoxies of the past; or he believes that “woke” silliness is a sideshow to measurable achievement in the real world of money, management, medicine, and the metaverse. He is happy to traffic in—and help produce—the utilitarian fruits of the West without wondering very much about how we got here, where we are going. or what could go wrong.

The Isolationist Jew has an entirely different metaphysical compass. He believes that the practice and preservation of Jewish life is the core purpose of education, and that worldly knowledge is only valuable inasmuch as it sustains a Torah-centered life. He sees the Jew as a permanent outsider: a holy (but vulnerable) bystander in a world of lesser (but more powerful) nations. He seeks to separate himself from the messy struggle to renew the West and sees his community as too small to matter even if he tried. And while he recognizes that the best of non-Jewish culture in art, music, and literature may have merit, the Isolationist Jew affords neither the time nor resources to pay it real attention; and he believes that it is better to ignore (or downplay) the West than to open up young, impressionable Jews to its temptations.

In radically different ways, the Assimilated Jew and the Isolationist Jew both declare that Western civilization is not their problem: the Assimilated Jew falsely takes Western “progress” for granted; the isolationist Jew falsely sees Western decadence as inevitable; and neither takes any Jewish responsibility for the very Western culture that the Israelites helped create. What is wrong—asks the Assimilated Jew—with seizing the opportunities of the modern age, unencumbered by outdated books, outdated questions, and outdated religions? What is wrong—asks the Isolationist Jew—with focusing entirely on Torah learning, undistracted by the inferior ideas and values of non-Jewish peoples and cultures? Both assume that they can survive and thrive without concerning themselves about the past, present, and ultimate purpose of Western civilization. And both are sadly wrong, because both ignore how fragile Western civilization really is, or what would happen to the Jews if the West truly crumbles.

Let us celebrate, instead, the Menorah Jew, who proudly seeks to help renew the West by shining a Jewish light in the modern age: one teacher, one classroom, one Jewish day school at a time. For whether we accept it or not, the Jews will never be a normal nation. We have an exceptional place in the human story. As the Jewish intellectual Milton Himmelfarb famously quipped, the Jews are no bigger than a rounding error in the Chinese census, and yet we always find ourselves at the center of the human drama. And so we will either prepare the rising generation of Jews to navigate the Western world—and to help save the woke West from canceling itself—or we will send our Jewish boys and girls down the lesser paths of assimilation or isolation. The heroes in this story—as in so many eras of Jewish history—will be the school-builders. As Rabbi Samson Raphael Hirsch summoned us many years ago:

If ever a cause required the clarity of profound insight, the eloquence of deep-felt conviction and the impetus of ardent zeal, if ever there was a cause for which we would rouse all those hearts that can still be moved to genuine feeling for the sacred heritage of Judaism, then it most certainly is that of education—Jewish education.

“Create schools! Improve the schools you already have!” This is the call we would pass from hamlet to hamlet, from village to village, from city to city; it is the appeal to the hearts, the minds and the conscience of our Jewish brethren, pleading with them to champion that most sacred of causes—the cause of thousands of unhappy Jewish souls who are in need of schools, better Jewish schools, for their rebirth as Jews.

More about: Education, History & Ideas, Jewish education, Politics & Current Affairs