The biblical book of Genesis presents the story of how God’s new way for humankind finds its first adherent in a single individual—Abraham, a man out of Mesopotamia—and how that way survives through three generations in the troubled households of Abraham, his son Isaac, and his grandson Jacob, who is renamed Israel. By the end of Genesis and the beginning of Exodus, the children of Israel are settled in Egypt, a land of good and plenty, where they are soon teeming and prospering—only, a brief time thereafter, to find themselves subjugated and enslaved. How this multitude becomes transformed into a people, out of and against Egypt, is the subject of Exodus and the following books.

The central event in the national founding of the Israelite people is the giving of the Law at Mount Sinai. The “Ten Commandments” (Exodus 20: 1-14), pronounced there by the Lord God to the assembled and recently liberated children of Israel, constitute the most famous teaching of the book of Exodus, perhaps of the entire Hebrew Bible. Prescribing proper conduct toward God and man, the Decalogue embodies the core principles of the Israelite way of life and, later, of what would become known as the Judeo-Christian ethic. Even in our increasingly secular age, its influence on the prevailing morality of the West is enormous, albeit not always acknowledged or welcomed.

Yet, despite its notoriety, the Decalogue is still only superficially known, in part because its very familiarity interferes with a deeper understanding of its teachings. This essay, in aspiring to such an understanding, intends also to build a case for the enduring moral and political significance of the Decalogue—a universal significance that goes far beyond its opposition to murder, adultery, and theft.

1. Structure and Context

We can begin by correcting some common misimpressions, starting with the name “Ten Commandments.” Although most of the entries in the Decalogue appear in the imperative mode (“Thou shalt” or “Thou shalt not”), they are not called commandments (mitzvot) but rather statements or words: “And God spoke all these words.” Later in the Bible we hear about the ten words—in the Greek translation, deka logoi or Decalogue—but whether the reference is to these same statements is far from obvious.

No help is provided by counting. Traditional exegetes derived as many as thirteen “commands” from God’s speech in Exodus 20, and because internal divisions within particular statements are unclear, even those who agree on the number ten disagree on how to reckon them. Furthermore, no mention is made in Exodus 20 of the famous tablets of stone on which, in traditional imagery, we see the Decalogue inscribed, five statements on each. When such tablets are mentioned later on, we are not told what is written on them.

What then do we know about the structure of these pronouncements? One group of them touches mainly on the relation between God and the individual Israelite: the first words spoken are “I the Lord [am] thy God,” and within this group we hear the phrase “the Lord thy God” four more times. The second group (beginning with “Thou shalt not murder”) touches primarily on conduct between and among human beings; in this section God is not mentioned, and the very last word of the Decalogue, “thy neighbor,” marks a far distance from the opening “I the Lord.”

Next, nearly all of the statements are formulated in the negative. The first few statements proscribe wrongful ways of relating to the divine—no other gods, no images, no vain use of the divine name—while the last six begin with lo, “not.” Human beings, it seems, are more in need of restraint than of encouragement.

In this sea of prohibition, two positive exhortations stand out: the one about hallowing the Sabbath, and the one about honoring father and mother. Hallowing the Sabbath is also one of two injunctions that receive the longest exposition or explanation; the other one concerns images and likenesses. Clearly, these three deserve special attention.

But far more important than structural features is the context into which the Decalogue fits. This is the new, people-forming covenant proposed by God through His prophet Moses to the children of Israel in the antecedent chapter of Exodus (19:5-6). The overall terms of that agreement are succinctly stated. If the children of Israel (a) “will hearken unto My voice” and (b) “keep My covenant,” then, as a consequence, (a) “ye shall be Mine own treasure from among all peoples” and (b) “ye shall be unto Me a kingdom of priests and a holy nation.”

It is only here, with the offer of a divine covenant, that this motley multitude of ex-slaves learns for the first time that they can become a people, among the other peoples of the earth, and that they can become a special people, a treasure unto the Lord. Moreover, their special place is defined in more than political terms: they are invited to become a kingdom of priests and a holy nation. This is a matter to which we will return.

Yet the Decalogue is hardly the bulk of the Torah’s people-forming legislation. All of the laws specifying proper conduct and “religious” observance come later: first in the ordinances immediately following the giving of the Decalogue, then in the laws regarding the building of the tabernacle, and then, in the book of Leviticus, in the law governing sacrifices and the so-called Holiness Code. So the Decalogue functions rather as a prologue or preamble to the constituting law. Like the preamble to the Constitution of the United States, it enunciates the general principles on which the new covenant will be founded, principles that in this case touch upon—and connect—the relation both between man and God and between man and man. It is less a founding legal code, more an orienting aspirational guide for every Israelite and, perhaps, every human heart and mind.

2. The Lord, Thy God

The Decalogue is introduced as follows: “And God spoke all these words, saying” (Exodus 20:1). Unlike most such biblical statements reporting a divine act of speaking, this one does not identify the audience. But the omission is fitting, for the speech appears to be addressed simultaneously to all the assembled people and to each one individually: in fact, all of the injunctions are given in the second person singular. Moreover, although pronounced at a particular time and place, and uttered in the presence of a particular group of people, the content of the speech is not parochial. It is, rather, addressed to anyone and everyone who is open to hearing it—including, of course, us who can read the text and ponder what it tells us.

If the identity of the audience is unspecified, that of the speaker is plain: “I [the] Lord am thy God, who brought thee out of the land of Egypt, out of the house of bondage” (Exodus 20: 2). Later Jewish—but not Christian—tradition will treat this assertion as part of the first statement and the basis of the first positive precept: to believe in the existence of the one God. But in context it functions more to announce the identity of the speaker—who, as would have been customary in any such proposed covenant between a suzerain and his vassals, declares the ruler-subject relationship that governs everything that follows. On this understanding, “I the Lord am thy God” emphasizes that the speaker is the individual hearer’s personal deity: not just the god of this locale, capable of making the mountain tremble, rumble, and smoke, but the very One who brought you personally out of your servitude in Egypt.

Nor, unlike God’s self-identification to Moses at the burning bush (Exodus 3:6), is there any mention here of the patriarchs. The agreement offered to the Israelites is a covenant not with the God of their long-dead fathers but with the God of their own recent deliverance. The former covenant was for fertility, multiplicity, and a promised land; the new one concerns peoplehood, self-rule, and the goals of righteousness and holiness. It rests on a new foundation, and it is made not with a select few but with the universal many.

Although the basis of the new relationship is historical, rooted in the Lord’s deliverance of the Israelites from Egyptian bondage, the Lord’s opening declaration also conveys a philosophical message. The Lord appears to be suggesting that for the children of Israel—if not also for other unnamed auditors—there are basically two great alternatives: either to be in relation to the Lord, in Whose image humankind was created, or to be a slave to Pharaoh, a human king who rules as if he were himself divine. Egypt, identified redundantly as “the house of bondage,” is presented here not just as one alternative among many but as the alternative to living as men and women whose freedom—from bondage not only to Pharaoh but to their own worst tendencies—seems to depend on embracing the covenant with the Lord.

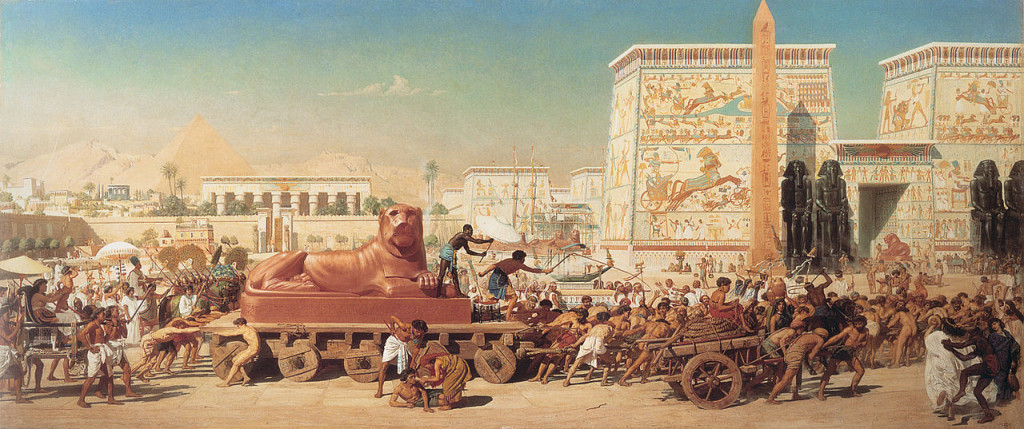

Israel in Egypt Edward Poynter, 1867. Guildhall Art Gallery, London.

3. How Not to Seek God

After the opening remark declaring God’s relation to this people, the next statements concern how God wants them to conduct their side of the relationship. The instruction is entirely negative.

The first wrong way is this: “Thou shalt not have other [or “strange”; aherim] gods before Me” (Exodus 20: 3). This is a declaration not of philosophical monotheism but of cultural monotheism. What is claimed precisely is an exclusive, intimate I-thou relationship like that of a marriage, requiring unqualified fidelity and brooking no other’s coming between the two partners. One might phrase it this way: “Thou shalt look to no stranger-gods in My presence.” This goes beyond turning an I-thou relation into a “triangle.” Aherim, the word translated “other” or “strange,” suggests that any such putative deities would be alien not only to the relationship as such but specifically to its human partners. The only God fit for a relationship with beings made in God’s image is the God whose being they resemble and whose likeness they embody. Only such a One would not be a “stranger.”

Yes, powers regarded (not unreasonably) by other peoples as divine—for example, the sun, the moon, the earth, the sea, the mountain, or the river—may play a decisive role in determining the character and events of human life. Yes, the powers that the Greek poets presented as anthropomorphic gods—Poseidon, earth-shaker; Venus, source of erotic love; Demeter, source of crops; warlike Ares—must be universally acknowledged and respected for their place in human life. But one cannot truly have a relationship with them, for they are strangers to all those who look to them. Only with the Lord God is there the possibility of genuine kinship.

Having established the principle of exclusivity, God speaks next to correct a second error, namely, the natural human inclination to represent the divine in artfully made visible images, and even to worship these statues or likenesses:

Thou shalt not make unto thee a graven [or “sculptured”] image, nor any likeness of any thing that is in the heavens above or that is in the earth below, or that is in the water under the earth; thou shalt not bow down unto them, nor serve them, for I the Lord your God am a jealous god, remembering [or “visiting”] the iniquity of the fathers upon the children unto the third or fourth generation of them that hate Me; and showing grace unto the thousandth generation of them that love Me and keep My commandments. (Exodus 20: 4-6)

Intended to proscribe the worship of idols, this injunction builds a fence against such practices by forbidding even the making of sculpted images or likenesses, especially of any natural being. It emphatically opposes the practice, known to the ex-slaves from Egypt, of worshipping natural beings—from dung beetles to the sun to the Pharaohs—and representing them in sculpted likenesses. But it also seems to preclude any attempt to represent, in image or likeness, God Himself. The overall message is clear: any being that can be represented in visible images is not a god. The unstated reason: God is incorporeal and trans-natural.

What’s wrong with worshipping visible images or the things they represent? Even if, as we have reason to believe, it rests on an error—mistaking a mere likeness for a true divinity—it seems harmless enough, at most a superstitious waste of time. But the practice and the disposition behind it are hardly innocuous. To worship things unworthy of worship is in itself demeaning to the worshiper; it is to be oriented falsely in the world, taking one’s bearings from merely natural phenomena that, although powerful, are not providential, intelligent, or beneficent. Moreover, paradoxically, such apparently humble submission masks a species of presumption. After all, human beings will have decided which heavenly bodies or which animals are worthy of being revered, and how these powers are to be appeased. In addition, the same human beings believe that they themselves, through artful representation, can fully capture these natural beings and powers and then, through obeisance, manipulate them. Worse, with increased sophistication of the craftsmen comes the danger that people will come to revere not the entities idolized but the physical idols as well as the sculptors and painters who, in making them, willy-nilly elevate themselves.

Perhaps the most important reason is that neither the worship of dumb nature nor the celebration of human artfulness addresses the twistedness and restlessness that lurk in the human heart and soul. To put the point positively, neither nature nor artfulness teaches anything about righteousness, holiness, or basic human decency. Indeed, the worship of nature or of idols may contribute to the problem. Making the connection explicit, the Lord vows to visit the “iniquities” of the fathers on the sons, unto the third or fourth generation.

An iniquity (avon) in the Bible differs from a sin (het). To sin is to miss the mark, as an arrow misses the target. By contrast, to commit an iniquity is to do something twisted or crooked, to be perverse. Sin is not inherited, and only the sinner gets punished; iniquity, however, like “pollution,” lasts and lasts, affecting those who come in its wake. It is not only that perverse fathers are likely to pervert their children; in addition, the children are inevitably stained by the father’s iniquity. How this comes about, the text leaves wonderfully ambiguous, thanks to the multiple meanings of the Hebrew verb poqed, which means both visiting and remembering; either the Lord promises to intervene directly and actively inflict the father’s twisted deeds on the sons, or He promises to allow those deeds to linger in the fabric of the world, contaminating the lives of the sons until repentance or cleansing is effected. Either way—and perhaps the two amount to the same thing—the perversity of the father’s deeds will reverberate through the generations.

The Israelites are not yet told what behavior they are to regard as iniquitous. Is it idolatry itself, or does idolatry lead to such twisted practices as incest, fratricide, bestiality, cannibalism, slavery? One way or the other, the fathers (and mothers) are put on notice: how they stand with respect to divinity will affect their children and their children’s children. God and the world care about, retain, and perpetuate our iniquities.

But not indefinitely—only to the third or fourth generation, the limits of any father’s clearly imaginable future. And overshadowing all is the promise of God’s bountiful grace “to the thousandth generation of those who love Me and keep My commandments.” Just as the sons of iniquitous fathers suffer through no direct fault of their own, so a thousand generations of descendants of a single God-loving and righteous ancestor enjoy unmerited grace. (By the way, it has been only 200 generations since the time of Father Abraham, for whose merit the children of Abraham are still being blessed.)

From this little injunction on idol-worship we learn that God and the world are not indifferent to the conduct of human beings; that our choice seems to be between living in relation to the Lord and worshipping or serving strange gods, between keeping His commandments and living iniquitously; that the choices we make will have consequences for those who come later; but that the blessings that follow from worthy and God-loving conduct are more far-reaching than are the miseries caused by iniquitous and God-spurning conduct. There will be perversity in every generation, but the world overflows with hesed or grace.

And this surprising turn in the comment on idolatry and iniquity highlights the decisive (and perhaps most important) difference between idols or strange(r) gods and “the Lord thy God”: under the rule of no other deity could the world be seen to embody the kind of grace, kindness, and blessing here foretold. As earlier in the hope-filled rainbow sign after the flood (Genesis 9: 1-17), the token of God’s first covenant with humankind, here each and every Israelite learns that he will have reason to be grateful not only for his one-time recent deliverance from Egypt but also for the enduringly gracious (and not merely powerful or dreadful) character of the deity with whom he is covenanting.

The implications for how we are to live in the light of this teaching are clear. My children and my children’s children are at risk from any iniquity I commit; but nearly endless generations will benefit from the good that I may do. An enormous responsibility, then; and yet we know also that we are not solely responsible for the world’s fate, and that redemption is always possible. Even if we fail, there will still be hesed. To walk with hope in the light of hesed offers the best chance for a worthy life.

The final error to be corrected concerns the use of the divine name. For if visible beings are unworthy of worship, and if, conversely, “the Lord thy God” cannot be visibly imaged, all that remains to us of Him (when He is silent) is His name. Yet it is also not through His name that the Israelites are to enter into a proper relationship with the Lord:

Thou shalt not take up (nasa) the name of the Lord thy God in vain, for the Lord will not hold guiltless the one who takes up His name in vain. (Exodus 20: 7)

Without warning, and for no apparent reason, the Lord speaks now of Himself not in the first but in the distant third person. This distancing fits with the progressive distance from “thy God,” to “other/stranger gods before Me,” to vain “images and idols” not to be made and worshipped, and now to “the name of the Lord thy God” that is not to be taken in vain.

The prohibition itself, though seemingly straightforward, asks to be unpacked. What, exactly, is being proscribed? What sort of use of God’s name is “in vain”? The concept embraces not only speaking falsely but also speaking emptily, frivolously, insincerely. The most likely occasion for such empty invocations of the divine name would be in swearing an oath, calling on God to witness the truth of what one is about to say or the pledge one is promising to fulfill. But the injunction seems to have a larger intention, at the very least inviting us to ponder what would not be a vain use of the Lord’s name.

The real target of the injunction may be the attempt to live in the world assuming that “God-is-on-our-side.” That is, what is “vain” about the forbidden speech may have more to do with an inward disposition of the heart than with words overtly spoken. To speak the Lord’s name, unless instructed to do so, is to wrap yourself in the divine mantle, to summon God in support of your own purposes. It is to treat God as if He were sitting by the phone waiting to do your bidding. In the guise of beseeching the Lord in His majesty and grace, one behaves as if one were His lord and master. One behaves, in other words, like Pharaoh.

There is a deeper issue, having to do less with misconduct and more with the hazards of speech itself. Treating anyone’s name as something that one can “take up” or “lift” is to take him up, as if by his handle. Like making images of the divine, trafficking in the divine name evinces a presumption of familiarity and knowledge. To handle the name of the Lord risks treating Him as a finite thing known through and through. Even if uttered in innocence, the use of the Lord’s name invites the all-too-human error that attends all acts of naming: the belief that one thereby knows the essence.

Called by God from out of the burning bush, Moses, in the guise of asking what to respond when the Israelites inquire who sent him, seeks to know God’s name. The profoundly mysterious non-answer he receives—ehyeh asher ehyeh, I will be what I will be, or I am that I am—is in fact a rebuke: the Lord is not to be known or captured in any simple act of naming. The right relation to Him is not through naming or knowing His nature but through hearkening to His words. The right approach is not through philosophy or theology, not through speaking about God (theo-logos), but through heeding His speech.

This is not to say that the Decalogue proscribes all speaking about God. Later, there will be instruction about times and circumstances in which the Israelites will be enjoined to call upon or to praise the Lord; and the mention of His name in regular rituals and prayers can hardly be taken as a violation of this injunction. At the same time, however, the proscription does serve to induce caution. By avoiding casual speech about the Lord, one leans especially against the cultivation of a childish view of the deity—a super-powerful fellow with a beard, accessible on demand, intelligible, familiar: a projection, in short, of our own needs and imaginings. And it makes clear that our relation to the divine is not to proceed by way of naming speech any more than by way of visible likeness.

Yet, up to this point, there has been no positive instruction regarding how one should relate to the divine. What does this God want of His people? The next utterance gives the answer.

4. The Sabbath Day

Of all the statements in the Decalogue, the one regarding the Sabbath is the most far-reaching and the most significant. It addresses the profound matters of time and its reckoning, work and rest, and man’s relation to God, the world, and his fellow men. Most important, this is the only injunction that speaks explicitly of hallowing and holiness—the special goal for Israel in the covenant being proposed. Here is the relevant text:

Remember the Sabbath day, to keep it holy. Six days shalt thou labor and do all thy work. But the seventh day [is a] Sabbath to the Lord thy God.

Thou shalt do no manner of work, thou, thy son and thy daughter, thy servant and thy maidservant, thy cattle and thy stranger that is within thy gates.

For in six days made the Lord the heavens and the earth and the sea and all that is in them; but He rested on the seventh day; and therefore the Lord blessed the seventh day and He hallowed it. (Exodus 20: 8-11)

The passage opens with a general statement, specifying two obligations: to remember, in order to sanctify. Next comes an explication of the duty to make holy, comprising a teaching for the six days and a (contrasting) teaching for the seventh. At the end, we get the reason behind the injunction, a reference to the Lord’s six-day creation of the world, His rest on the seventh day, and His consequent doings regarding that day.

Imagine ourselves “hearing” this simple injunction at Sinai. We might find every term puzzling: what is “the Sabbath day”? What does it mean to “remember” it? And what is entailed in the charge, “to keep it holy” or “to sanctify it”? And yet the statement seems to imply that “the Sabbath day” is, or should be, already known to the Israelites. What might they have understood by it?

The word “sabbath” comes from a root meaning “to cease,” “to desist from labor,” and “to rest.” Where, then, have the ex-slaves encountered a day of desisting? Only in their recent experience with manna.

After the exodus from Egypt and their deliverance at the Sea of Reeds, the Israelites encounter shortages of water and food, and begin to murmur against Moses’ leadership. Comparing unfavorably their food-deprived new freedom with their well-fed existence in bondage, they long for the fleshpots of Egypt and accuse Moses of bringing them into the wilderness to die of hunger. As if waiting for just such discontent, the Lord intervenes even without being asked. He causes manna to rain from heaven for the people to gather, “a day’s portion every day,” not only to tame their hunger but explicitly “that I may prove them, whether they will walk in My law or not.” (Exodus 16:4) The restrictions placed on their gathering are threefold: each should gather only what he and his household need and can eat in a day; there is to be no overnight storage or waste; and there is to be no gathering on the seventh day, for which a double portion will be provided ahead of time on the sixth.

The provision of the manna, and the restrictions attached to its gathering and storage, teach several lessons: the condition of the world is not fundamentally one of scarcity but of plenty, sufficient to meet the needs of each and every human being; there is thus no need to hoard against the morrow or to toil endlessly, grabbing all you can; and there is no need to look upon your neighbor as your rival, who may keep you from a livelihood or whose need counts less than yours. Accordingly, one may—one should—regularly desist from acquiring and provisioning, in an expression of trust, appreciation, and gratitude for the world’s bounty, which one also must neither covet beyond need nor allow to spoil. In all these respects, the provision of manna in the wilderness stands as a correction of fertile Egypt, where land ownership was centralized, acquisitiveness knew no respite, excesses were hoarded, the multitude sold themselves into slavery in exchange for grain, neighbor fought with neighbor, and one man ruled all as if he were a god.¹

Against the ex-slaves’ despairing belief that food is preferable to freedom and that serving Pharaoh offered the surest guarantee of life, the children of Israel are taught not only that they live in a world that can provide for each and every person’s needs but also that the Lord helps those who will help themselves. They must work to gather, but what they gather is a gift. In a world beyond scarcity and grasping, the choice is not freedom versus food and drink, but grateful trust versus foolish pride or ignorant despair.

Aside from their experience of manna, the Israelites may have had another referent for a “Sabbath day.” Before the coming of the Bible, many peoples in the ancient Near East already reckoned time in seven-day cycles connected with the phases of the moon. Among the Babylonians, these seventh days were fast days, days of ill luck, days on which one avoided pleasure and desisted from important projects out of dread of inhospitable natural powers. This was especially the case with their once-a-month Sabbath, shabattu or shapattu, the day of the full moon (i.e., the fourteenth day from the new moon).

Against these naturalistic views, the Sabbath teaching in Exodus institutes a reckoning of time independent of the motion of the heavenly bodies, in which the day for desisting comes always in regular and repeatable cycles and is to be celebrated as a day of joy and benison. Readers of Genesis already know the basis of this way of reckoning time from the story of creation, whose target was precisely those Mesopotamian teachings. But the children of Israel are only now learning that time in the world—and, hence, their life in the world—will be understood differently from the way other, nature-worshipping peoples understand it. The Sabbath day, blessed by the Lord, has existed from time immemorial; but the creation- and humanity-centered view of the world enters human existence only through the covenant being here enacted with the children of Israel.

What, then, is the duty to remember the Sabbath day? About some matters—such as their previous condition of servitude—the Israelites will be exhorted to keep in mind that which they previously experienced. About the Sabbath day—whose original, of course, no human being could have experienced—the Israelites are told to keep present in their minds that which the Lord is now telling them for the first time. Once they learn the reason behind the injunction, the duty to remember will link their future mindfulness with their recall of the remotest past: the original creation of the world and the beginning, or pre-beginning, of time. Each week, going forward, the children of Israel will be not only recalled to God’s creation of the world but invited symbolically to relive it.

Much later, when Moses repeats the Decalogue in Deuteronomy, he will enjoin the Israelites to “guard” (or “keep” or “observe”; shamor) the Sabbath day, to keep it holy, “as the Lord thy God commanded thee.” (Deuteronomy 5:12) Guarding and keeping are duties for the Sabbath day itself, but remembering it can and should take place all week long, reconfiguring our perception of time and its meaning. Under this radically new understanding, the six days of work and labor point toward and are completed by the seventh day and its hallowing. Mindfulness of sanctified time makes an edifying difference to the manner and spirit in which one lives and works all the time; and the remembered change in the meaning of time transforms and elevates all of human existence. Work is for the sake of a livelihood, but a livelihood has a new meaning when staying alive is seen to have a purpose beyond itself.

The root meaning of qadesh, to make holy, is to set apart, to make separate. Other peoples have their own forms of separation or sanctity: sacred places, sacred rituals and practices, sacred persons or animals. But in Israel what is made holy is not a special object, place, or practice, but the time of your life. How to make this time holy we learn in the sequel, but here the Israelite idea of holiness is connected to the distinction between work (or labor) and rest, as well as to the distinction between the things that are yours and the things that “belong” to God. The six days of work appear to be “for yourself and your own”; by contrast, the seventh day is said to be a Sabbath unto the Lord thy God, on which day “labor [avodah] for oneself” is replaced by “service [avodah] to the Lord.”

Yet the form of devotion is odd. No rituals or sacrifices are specified; on the contrary, what is required is an absence, a cessation, a desisting, and this obligation to desist falls on the entire household. From master to servant to beast and stranger, the worldly hierarchy is to be set aside; regardless of rank or station, all are equally invited to participate in the hallowing of the day. Nor do people need to travel or to sacrifice in order to encounter this sanctified time. Holiness has a central and ever-renewable place in their ordinary life at home, if they but keep it in mind.

And the key to the holiness that is the Sabbath’s desisting from labor? It is nothing less than God’s own doings in connection with creation. Every week the children of Israel are, as it were, returned to the ultimate beginning and source of the world, summoned to remember and to commemorate its divine creation and Creator.

This means, among other things, remembering that what we call “nature” and was once widely worshipped—heaven, earth, sea, and all they contain—is not in fact divine but rather the aggregate of God’s creations and creatures. At the same time, in remembering the majestic fact of creation and the world’s plentitude and beauty, the Israelites are also taught not to disdain the world or regard it as hostile, malevolent, or inhospitable, but rather to see it as a generous gift for whose bounty and blessings all human beings can and should be grateful.

The Israelites are not only recalled to the creation; their own weekly cycle of work and desisting is meant, symbolically, to reproduce it. Here is the most radical implication of the Sabbath teaching: the Israelites are, de facto, enjoined “to be like God”—both in their six days of work and especially on the day of desisting. Note well: their relationship to the Creator is no longer based solely in historical time and in their (parochial) deliverance from Egyptian bondage. It is also ontologically rooted in cosmic time and in the universal human capacity to celebrate the created order and its Creator, and in our special place as that order’s god-like, God-imitating, and God-praising creatures.

It is, of course, peculiar to command us to rest as God rested, because it is peculiar to speak of God “resting.” Nevertheless, we can conjecture something of what it might mean.

In the original account of creation, at the end of the sixth day “God saw every thing that He had made and, behold, it was very good.” But the true completion of creation comes on the seventh day, only after the creative work had ceased:

And the heaven and the earth were finished and all their host. And God finished on the seventh day His work which He had made and He desisted on the seventh day from all His work which He had made. And God blessed the seventh day and He hallowed it, because on it He desisted from all His work which God created to make. (Genesis 2: 1-3)

Here there is no talk of resting but only of desisting and, on that account, of blessing and hallowing (or setting apart) the seventh day. A complete world of changeable beings has been brought into being by a divinity Who then completes His creative makings by “standing down.” In this mysterious blessing and hallowing of time “beyond” the world of creative making, God, as it were, makes manifest in the rhythm of the world itself that mysterious aspect of Being that is beyond change.

Remarkably, this consecration of time—and this pointing to what is “out of time”—is something we (and only we) humans can glimpse and participate in. It is open to us if and when we set aside our comings and goings, and turn our aspirations toward the realm beyond motion from which motion derives. It is open to us when we are moved by wonder and gratitude for the existence of something rather than nothing, for order rather than chaos, and for our unmerited presence in the story.

It may seem similarly odd to suggest that human beings would be imitating God by feeling gratitude; why, and for what, would God be grateful? Yet gratitude for the created world is also not itself part of the created world; literally a manifestation of grace, it stands us, however briefly, outside the world beyond the flux of the world’s ceaseless motions and changes. Although mobile beings ourselves, we alone, god-like among the creatures, are capable of standing outside and contemplating the world and feeling gratitude for it and our place in it. In this respect, too, Sabbath remembrance and sanctification permit us to be “like God.”

The existence of Sabbath rest thus offers a partial reprieve from the sentence of unremitting toil and labor prophesied by the Lord at the end of the story of the Garden of Eden—a “punishment” of the human attempt to become like gods, knowing good and bad, undertaken in an act of disobedience. According to that account, our prideful human penchant for independence, self-sufficiency, and the rule of autonomous human reason led us into a life that, ironically, would turn out to be nasty, brutish, and short. This is still very much our lot. But here, with Sabbath desisting, we are not only permitted, we are in fact obliged regularly to cease the life of toil, sorrow, and loss and to accept instead the god-like possibility of quiet, rest, wholeness, and peace of mind.

And this rise to godlike peace, unlike the self-directed “fall” into the knowledge of good and bad, depends not on disobedience but on obedience: the only way a free and reckless creature like man can realize the more-than-creaturely possibility that was given to him at the creation. It is not only or primarily in imitating God in our workaday labor, but mainly and especially in hearkening to a command to enter into sacred time, that we may realize our human yet godlike potential. Doing as I say, teaches the Lord, is the route to “doing as I did” (or “being as I am”).

The Sabbath teaching has other profound implications for human life, including especially for politics. Adherence to the Sabbath injunction turns out to be the foundation of human freedom, both political and moral. By inviting and requiring all members of the community to imitate the divine, it teaches the radical equality of human beings, each of whom may be understood to be equally God’s creature and equally in His image.

Sabbath observance thus embodies and fosters the principle of a truly humanistic politics. Although not incompatible with political hierarchy (including kingship), the idea behind the Sabbath renders illegitimate any regime that denies human dignity or that enables one man or some few men to rule despotically as if he or they were divine. And by reconfiguring time, elevating our gaze, and redirecting our aspirations, Sabbath remembrance promotes internal freedom as well, by moderating the passions that enslave us from within: fear and despair (owing to a belief in our lowliness), greed and niggardliness (owing to a belief in the world’s inhospitality), and pride and hubris (owing to a belief in our superiority and self-sufficiency).

The deep connection between the Sabbath and political freedom is supported by the repetition of the Decalogue in Deuteronomy. There, the reason given for Sabbath observance rests not on God’s creating the world but on the exodus from Egypt:

And thou shalt remember that thou wast a slave in the land of Egypt, and the Lord thy God brought thee out thence with a mighty hand and a outstretched arm; therefore, the Lord thy God commanded thee to keep the Sabbath day. (Deuteronomy 5:15; emphasis added)

In place of the six days of God’s creative work contrasted with the seventh day of divine rest and sanctification, the Deuteronomic version contrasts the Israelites’ enforced labor in Egyptian servitude with the Lord’s mighty deliverance. The substitution invites us to see the second justification for Sabbath observance as the logical analogue and consequence of the first. In a word, where men do not know or acknowledge the bountiful and blessed character of the given world, and the special relationship of all human beings to the source of that world, they will lapse into worship either of powerful but indifferent natural forces or of powerful and clever but amoral human masters and magicians.

These seemingly opposite orientations—the worship of brute nature and the veneration of clever men—amount, finally, to the same thing: both deny the special god-like standing and holy possibilities of every single human being, and of humanity as such. Called upon to remember what it was like to have lived where men knew not the Creator in whose image we humans are made, and called upon to remember the solicitude of the Creator for His suffering people, the Israelites will embrace the teaching about Sabbath observance, and their politics will be humanized and their lives elevated as a result.

5. Honoring Father and Mother

The Decalogue moves next to its only other positive injunction, which is also the first to prescribe duties toward human beings and the last to mention “the Lord thy God.” Standing as a bridge between the two orders of duty—to God and to one’s fellow men—it also invites us to consider what the one has to do with the other:

Honor thy father and thy mother,

So that thy days may be long

Upon the land which the Lord thy God

giveth thee. (Exodus 20: 12)

As children of the civilization informed by the Bible, we take for granted that the duty of honor is owed to both father and mother, and equally so. Yet this obligation is almost certainly an Israelite innovation. Against a cultural background giving pride of place to manly males and naming children only through their patronyms, the Decalogue trumpets a principle that regards father and mother equally. Well before there is any explicit Israelite law regarding marriage, this singling out of one father and one mother heralds the coming Israelite devotion to monogamous union, with clear lines of ancestry and descent and an understanding of marriage as devoted to offspring and transmission. Moreover, the principle is stated unconditionally: God does not say, “Honor your father and mother if they are honorable.” He says, “Honor them regardless.” We will soon consider why.

As children of the civilization informed by the Bible, we probably also take for granted that our parents should be singled out for special recognition. But this is hardly the natural way of the world. Not only is the natural family the nursery of rivalry and iniquity, even to the point of patricide and incest, but honor in most societies is usually reserved not for Mom and Dad but for people out of the ordinary, for heroes, rulers, and leaders who go, as it were, in the place of gods.

Calling for the honoring of father and mother is thus another radical innovation, a rebuke at once to the ways of other cultures, to the natural human (and especially male) tendency to elevate heroes and leaders, and to the correlative quest for honor and glory in defiance of human finitude. In place of honoring the high and mighty, the way of the Lord calls for each child’s honoring his or her father and mother, in the service of elevating what they alone care for and do: the work of perpetuation. And by elevating equally the standing of both, each child also learns in advance to esteem his or her spouse, as well as their joint task as transmitters of life and a way of living in which perpetuation is itself most highly honored.

The Israelites will shortly be told more about what it means not to honor father or mother, and how seriously this failure is regarded. In the ordinances following the Decalogue, two of the four capital offenses (on a par with premeditated murder and kidnapping for slave-trading) are striking one’s father or mother and cursing one’s father or mother. But exactly what it means, positively, to honor is unspecified, and perhaps for good reason. By not reducing that obligation to specific deeds or speeches, the injunction compels each son or daughter to be ever attentive to what honoring father and mother might require, here and now. What the Decalogue is teaching here is a settled attitude of mind and soul.

Consider two alternative terms that might have been used to describe what children owe their parents: love and/or obedience. One can love or admire without honoring, and, conversely, one can honor even without loving or admiring. Yet for the Israelite, the duty to honor parents persists even if love is absent. As for obedience, the duty to honor father and mother extends long beyond the time when we, their children, are under their authority. An adult child may disagree with his father and mother, and choose to act in ways they would not approve; yet even when he does so, his unexceptionable and enduring obligation to honor them is still intact and binding.

Unlike the feeling of love, and unlike the wonder of admiration, both of which go with the grain, the felt need to honor (to give weight to; kabed) is not altogether congenial. For honor implies distance, inequality, looking up to another with deferential respect, reverence, and even something of fear. In this regard, honor is exactly like what is owed to a god, for it is rooted in the feeling of awe. Indeed, the link is later made explicit. When the Lord proclaims His central teaching about holiness, the injunction regarding the proper disposition toward father and mother is renewed, revised, and placed in remarkable company:

Ye shall be holy; for I the Lord your God am holy. Ye shall fear [revere] each man his mother and his father, and ye shall keep my Sabbaths. I [am] the Lord your God. (Leviticus 19:2-3)

Fear, reverence, and awe are, of course, precisely the disposition that is appropriate toward the Lord Himself: it was “fear/reverence of the Lord” for which Abraham was tested and praised in the binding of Isaac on Mount Moriah (Genesis 22:12). Moreover, the command to fear/revere mother and father is now clearly coordinated with the command to observe God’s Sabbath, making explicit the link between the two positive injunctions.

What, then, links the honoring of father and mother to Sabbath-keeping, and to “being holy”?

The teaching about “father and mother” comes right on the heels of the reason offered for sanctifying the Sabbath day: God’s creation of the world and His subsequent setting-apart and hallowing a time beyond work and motion. It thus extends our attention to origins and “creation,” now in the form of human generating. God may have created the world—and the whole human race—but you owe your own existence to your parents, who are, to say the least, co-partners—equally with each other, equally with God—in your coming to be. For this gift of life—and, one may pointedly add, for not aborting you or electing to contraceive the possibility of your existence—you are beholden to honor them, in gratitude.

Gratitude toward parents is owed not only for birth and existence, but also for nurture, for rearing, and especially for initiation into a way of life that is informed by the disposition to gratitude and reverence. The way of this “initiation” is itself a source of awe. For our parents not only teach us explicitly and directly regarding God, His covenant, and His commandments. In their devotion to our being and well-being, given us not because we merit it, they are also the embodiment of, and our first encounter with, the gracious beneficence of the world—and of its bountiful Source.

Filial honor and respect are not only fitting and owed; they are also necessary to the parental work, whose success depends on authority and command. Exercising their benevolent power by invoking praise or blame, reward or punishment, in response to righteous or wayward conduct, yet forgiving error and fault and remaining faithful to their children, parents embody and model the awe-some, demanding, yet benevolent and gracious authority that characterizes the Lord God of Israel. In response, on the side of the child, filial piety expressed toward father and mother is the cradle of awe-fear-reverence (and, eventually, love) of the Lord. Even when we no longer need their guidance, we owe them the honor due their office.

So the injunction to honor father and mother is fitting and useful. But why has it such prominence in the Decalogue, and why, paired with the Sabbath, is it at the heart of God’s new way and the summons to holiness? On the assumption that God reserves His most important teachings to address those aspects of human life most in need of correction, we need to remind ourselves of the problems this injunction is meant to address: the dark and tragic troubles that lurk within the human household and that, absent biblical instruction, imperil all decent ways of life. I refer to the iniquities of incest and patricide.

The Bible’s first and only previous mention of “father and mother” is found in a comment inserted into the story of the Garden of Eden—after the man, seeing and desiring the newly created woman, expostulates, “This one at last is bone of my bone and flesh of my flesh,” and then names her as if she were but a missing portion of himself: “She shall be called Woman because from Man she was taken.” At this point, interrupting the narrative, the text interjects:

Therefore a man leaves his father and his mother and cleaves unto his woman, that they may become as one flesh. (Genesis 2: 24)

Many commentators have seen here the ground of a biblical teaching about monogamous marriage. In my view, the context suggests something darker. The inserted exhortation comes right after a speech implying that love and desire—including especially (male) sexual desire—is primarily love and desire of one’s own: “bone of my bone and flesh of my flesh.” Leaving your father and mother in order to become “as one flesh” with an outside woman serves as a moral gloss not on monogamy but on the sexual love of your own flesh, which, strictly speaking, is the formula for incest.

The danger of incest, destroyer of the distance between parent and child, is tied to a second threat: resentment of and rebellion against paternal authority, up to and including murder. The Bible’s first story about the relation between father and sons, the story of Noah’s drunkenness, is, in fact, a tale involving at least metaphorical patricide. Told as the immediate sequel to the establishment of the Lord’s first covenant with all humanity, the story serves as a crucial foil for the teaching about family life that God now at Sinai means to establish in the world.

Noah has just received the first new law, comprising the basis for civil society, away from the anarchic “state of nature” that was the antediluvian world. At its center is the permission to kill and eat animals but, in exchange, an obligation to avenge human bloodshed—an obligation that is said to turn on the fact that man alone among the animals is god-like:

Whosoever sheds man’s blood, by man shall his blood be shed; for in the image of God was man made. (Genesis 9:6)

And it concludes with the command to procreate and perpetuate the new world order:

As for you, be fruitful and multiply, swarm through the earth, and hold sway over it. (Genesis 9:7)

Noah’s Drunkenness James Tissot, ca. 1806-1902. Jewish Museum, New York/Art Resource.

We look to the sequel to see how well this creature, made in the image of God, fares under the new covenant, and the result is not cheering. Noah plants a vineyard, gets blind drunk, and lies uncovered in his tent, stripped not only of his fatherly authority but even of his upright humanity. There he is seen in his shame by Ham, his hotheaded son, who goes outside and publicizes his discovery, celebrating his father’s unfathering of himself. Ham’s brothers, Shem and Japheth, enter the tent, walking backward, covering their father’s nakedness without witnessing or participating in it. When Noah awakens, he curses Canaan son of Ham but calls forth a blessing on “the Lord, God of Shem,” the son whose pious action restored him to his fatherly dignity and authority.

In explicating this story elsewhere (The Beginning of Wisdom: Reading Genesis, Chapter 7), I have suggested that it is intended to show how rebellion, incest, and patricidal impulses lurk in the bosom of the natural—that is, the uninstructed—human family. These dangers must be addressed if a way of life is to be successfully transmitted, especially a way of life founded on reverence for the Lord in whose image—as Noah and the human race have just discerned—we human beings are made.

The impulse to honor your father and mother does not come easily to every human heart. Yet some children appear to get it right, even without instruction. Shem, who restores his father’s paternal standing, seems to have divined the need for awe and reverence for his father as a pathway to, and manifestation of, the holy. And Shem’s merit, it turns out, is visited upon his descendants: he becomes the ancestor of Abraham, founder of God’s new way. Ham, on the other hand, is the ancestor of the Canaanites and the Egyptians, whose abominable sexual practices will be the explicit target of the laws of sexual purity (in Leviticus 18) that are central to Israel’s mission to become a holy nation. It is at the end of this list of forbidden deeds, each proscribed as an iniquitous “uncovering of nakedness,” that the Lord pronounces the connection, mentioned earlier, among the call to holiness, awe and reverence for mother and father, and the observance of the Sabbath.

Summing up: the injunction to honor father and mother constitutes a teaching not only about gratitude, creatureliness, and the importance of parental authority. It insists on sacred distance, respect, and reverence, precisely to produce holiness, qedushah, in that all too intimate nest of humanity that often becomes instead a den of iniquity and a seedbed of tragedy. In Sabbath observance, a correction is offered against the (especially Egyptian) penchant for human mastery and pride that culminates in despotism and slavery. In honoring father and mother, a correction is offered against the (especially Canaanite) penchant for sexual unrestraint, including incest, that washes out all distinctions and lets loose a wildness incompatible with the created order and with living under the call to be a holy people. Adherence to these two teachings offers us the best chance for vindicating the high hopes the world carries for the creature who is blessed to bear the likeness of divinity.

The connections between the Decalogue’s two positive injunctions, and between both of them and the goal of holiness, shed light on the vexed questions of the universality versus the particularity of God’s teaching to Israel and of Israel’s special standing among the nations. Our interpretation implies that the call to holiness, although made only (or first) to the people of Israel, seeks to produce on earth a perfection not just of one people but of human beings as such. This is perhaps already implicit in the Israelites’ call to become a kingdom of priests, whether as example or as minister to the other peoples of the world. The universality becomes explicit with the reason for Sabbath remembrance and sanctification, as the Israelites are summoned to adopt a God-like perspective on the nature of time and the relation between motion and rest. All human beings can appreciate and imitate the divine activities of creating and hallowing because we are all equally related to the Lord whose divine image and likeness each one of us bears.

Yet, paradoxically, we are immediately reminded that universality, like holiness, requires remaining true to the necessary particularity of our embodied existence. For what could be farther from universality than the utterly contingent and non-interchangeable relationship that each person has to his singular father and mother? True, the parent-child relationship bears certain deep similarities to the relationship between the biblical God and any human being. But no one lives with the universal (or generic) Father and Mother, only with his own very particular ones. A person shows reverence for fatherhood and motherhood as such only by showing reverence for his own father and mother.

Beware the universalist who has contempt for the particulars; beware the lover of all humanity, or of holiness, who does not honor his own father and mother. For it turns out to be all but impossible to love your neighbors as yourself if you treat lightly your most immediate “neighbors,” those who are not only most emphatically your own but also most able to guide you to your full humanity. The case for a parochial community that bears a universal way—hence the case for the distinctive nation of Israel—follows directly from these considerations.

From the Lord’s (or the Decalogue’s) perspective, indeed, the contingency and parochial character of our existence is not a misfortune or a defect. To the contrary, in the Torah it is an estimable blessing that we have bodies and live concrete and parochial lives, for it is only in and through our lived experiences, here and now, that we gain full access to what is universally true, good, and holy. Unlike a later scriptural teacher, the Lord of the Decalogue does not exhort you to leave your father and your mother, and follow me (Matthew 10:34-38). Instead, He celebrates the fact that grace comes locally and parochially, into the life each one of us was given to live as well as we can, embedded in the covenantal community into which we have been blessed to be born.

6. The “Second Table”: Moral Principles for Neighbors

When we move to consider the statements of the so-called “second table” of the Decalogue, we find ourselves on more familiar legal and moral ground, which we can thus cover more expeditiously.

Murder, adultery, and theft are outlawed by virtually all civilized peoples. These legal prohibitions not only form the necessary condition of civil peace; they erect important boundaries, not to be violated, between what is mine and what is thine: life, wife, property, and reputation. Because they stand to reason and because they were established already in the ancient Near East, they need neither explanations nor promises of punishment (or reward) for violation (or compliance).

And yet the Decalogue is not a legal code, and it goes beyond existing law. Formulated in absolute terms, the lapidary two-word Hebrew style of these latter statements sets them forth as eternal and absolute moral principles. In addition, packaged within the God-spoken preamble to the specific covenant with Israel, the principles acquire elevated standing as sacred teaching, ordained by a divine law-giver and resting on ontological ground firmer than mere human agreement or utilitarian calculation:

Thou shalt not murder.

Thou shalt not commit adultery.

Thou shalt not steal.

Thou shalt not bear false witness against thy neighbor.

Thou shalt not covet thy neighbor’s house; thou shalt not covet thy neighbor’s wife, nor his [man-]servant nor his maid-servant, nor his ox nor his ass, nor anything that is thy neighbor’s. (Exodus 20: 13-14)

The first three absolutes defend the foundational—rather than the highest—human goods: life, without which nothing else is possible; marital fidelity and clarity about paternity, without which family stability and responsible parenthood are very difficult; and property, without which one’s chance for living well—or even making a living—is severely compromised. Further specification of these principles must and will be given later in Exodus when the ordinances of the covenant are pronounced.

The proscription of bearing false witness carries a moral message that goes beyond its clear importance in judicial matters. At stake are not only your neighbor’s freedom, property, and reputation but also the character of communal life and the proper uses of the god-like human powers of speech and reason. Echoing the earlier prohibition on taking the Lord’s name in vain, this injunction takes aim at a deed of wrongful speech—speech that is, in fact, vain, light in weight and empty of truth. To speak falsely is to pervert the power of reasoned speech and to insult the divine original, whose reasoned speech is the source of the created order and the model of which we are the image.

If most of the prohibitions in the second table are familiar, the Decalogue concludes in a surprising turn by focusing not on an overt action but on an internal condition of the heart or soul, a species of ardent desire or yearning. The uniqueness of this proscription of coveting is suggested both by its greater length and by the spelling out of the seven things belonging to your neighbor that you not only must not steal but also must not even long for.

What is this doing at the close of the Decalogue? As a practical matter, a prohibition against covetous thoughts and desires builds a fence against the other forbidden deeds, for if you do not covet the things that are your neighbor’s, you will be less likely to steal, commit adultery, or even murder; and you will be less tempted to make your neighbor suffer harm or loss by bearing false witness against him.

But beyond such practical considerations, the final injunction causes us to reflect about the meaning of possession and about the nature of desire and neighborhood. A man who covets what is his neighbor’s suffers, whether he knows it or not, from multiple deformations of his own desire. Not content with his own portion of goodly things, he is incapable of seeing them in their true light: as means to—and participants in—a higher way of life.

Moreover, some of the same items occur on both the list of seven partakers in Sabbath rest and in the list of seven “covetables”—as if to indicate the mistaken direction of the coveter’s desire. His heart is set on the possessions of another because he fails to realize that the things that matter most are not the unsharable things but the things we and our neighbors have in common: knowledge of the Lord and what He requires of us, participation in His grace and the bounty of creation, and the opportunity to live a life of blessing and holiness, despite our frailty and penchant for error and iniquity.

Our neighbor’s aspiration to, or possession of, these goods in no way interferes with our chances to attain them. On the contrary, to live among neighbors who yearn for the sharable goods is to live in a true community, in which each and all can be lifted up in the pursuit and practice of holiness. Such a polity, even if only as an object of aspiration, is a veritable light unto the nations.

More about: Anthropomorphism, Bible, Biblical criticism, Decalogue, Leon Kass, premium, Reading Exodus with Leon Kass, Ten Commandments, Theology, Torah MiSinai