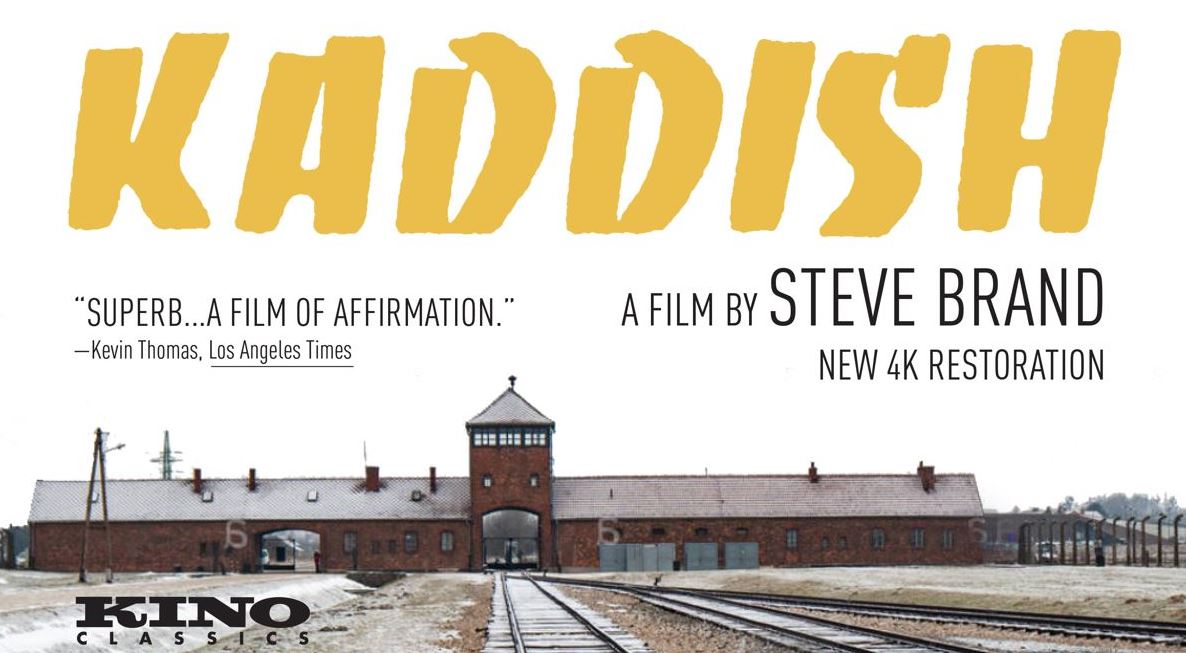

Last week, Mosaic invited subscribers to watch a free screening of Kaddish, a documentary that tells the story of how a young Jewish man, surrounded by Holocaust survivors, came to terms with his father, with his people, and with being Jewish after the Shoah. Afterwards, Yossi Klein Halevi, that young man and now a well-known Israeli writer, joined Mosaic’s editor Jonathan Silver for a special conversation. Watch and read the conversation below.

Watch

Read

Jonathan Silver:

Looking at the film Kaddish as a totality, I think it would be a mistake to say that this is simply a movie about the Holocaust—even if the Shoah and its legacy are a key part of the story the movie tells. It’s about much more: it’s about you and your father, it’s about the way that you both saw America, it’s about the way that you saw Israel. In your view, what is this film about?

Yossi Klein Halevi:

Well, I haven’t seen it in so many years. I know the plot. I know the main characters.

Jonathan Silver:

By the way, can you stand to watch it?

Yossi Klein Halevi:

I’ve seen bits of it over the years. I don’t think I would really want to sit through it from beginning to end. No, I really don’t feel pulled to see it. It used to be unbearable to me. When it first came out, I was already living in Israel and trying very consciously to distance myself from that person in the film. It’s been so many years. We started filming when I was twenty-four. My father died when I was twenty-five. I’m almost seventy, and it really is several lifetimes ago.

It’s not painful to watch in the way that it once was, but I don’t feel particularly pulled to it. One sweet thing about the film is that my kids were able to hear my father. When each of them turned either bar or bat mitzvah, I sat them down and I said, “Watch this.” My daughter was the oldest, she saw it first. After about twenty minutes, she said, “Do I have to see more?” I said, “I guess not.” That was it. I don’t know if she’s actually seen the whole film. She’s now thirty-seven. My two boys saw it, I think, straight through. They saw it and that was really important for me, not so much for them to see their father at an awkward age, but really to meet their grandfather. They knew their grandmother—my mother lived to a fairly old age. I can bear to see it, but again, I don’t see a reason to sit through and watch it again.

Jonathan Silver:

Is it right to understand this as a Holocaust documentary, or is it something else?

Yossi Klein Halevi:

When we first conceived of the film, our intention was to document the second generation, the children of the survivors. In fact, what we were going to do was focus on three families. We had our three families lined up. Unfortunately, we began with mine, and a year into the filming my father died. Then we all realized we have a compelling story. We kept the focus there. As soon as it became the story of one family and especially the death of a survivor, it really stopped being a synecdoche or an attempt to tell a generational story. I think it really told a very specific story, a story that resonates more widely in several ways.

It’s a story of a father and a son. It’s a story of how memory is transmitted and how an individual identity is formed in resistance to overwhelming historical memory. What do you retain and what do you give up? That’s so much a part of each of our personal growth. I also think it’s very much part of the story of the Jewish people. We obviously don’t remember everything. We can’t remember 4,000 years, so memory is selective. What we choose to let go of is often as important or more important than what we choose to remember. I think it’s a film about the impact of memory generally, about how memory works within a Jewish context. Then, even more specifically, about how memory works in the second generation.

Jonathan Silver:

There’s an orientation, I think, that crescendos throughout the film, but really comes to a culmination at the end. It’s an orientation away from Europe, first to America, and then toward Israel. Maybe we could just introduce the theme of Israel now. What role do you think Israel played? It would seem that to your father and, at that time, to you too, Israel represented a future.

Yossi Klein Halevi:

Yes, absolutely. Israel—and my father made this very clear to me from an early age—was his way of returning to Jewish faith. Israel made it passable for my father to go to synagogue.

Jonathan Silver:

I’ll note that your mother claims that role for herself in the film.

Yossi Klein Halevi:

My mother certainly returned my father to formal observance. That was her ultimatum. My father eventually became a believing Jew on his own, and it was because of Israel. I don’t think that that’s an unusual story among survivors. Israel made it possible for them at least to conceive of the Jewish story that we’ve told ourselves for thousands of years as being true. Maybe the story actually is true. Maybe the Jews really are this people that God chose for a specific purpose in the world.

My father, in the immediate years after the Holocaust, couldn’t bear that notion. The Nazis chose us. If anything, God chose us for a demonic fate. That was a very common attitude. When you read the great Yiddish and Hebrew poets—read Nathan Alterman, read Jacob Glatstein, writing about the Shoah in the immediate aftermath—the unbearable notion of chosenness is a recurring theme. My father said to me years later, “You know? I don’t know what it is about this people, but there’s something. There’s something about the Jews that doesn’t make sense.”

In a way, what he transmitted to me, my faith, as strange as it may sound, is very connected to the Shoah. I don’t only believe despite the Shoah—I do believe despite the Shoah—but I also believe because of the Shoah. What I mean there is that the story of the Jewish people, including the Shoah, and of course, especially Israel following the Shoah, is so strange. It’s such a surreal story that rational categories don’t work for it. Religion in some way always made sense to me in the way that I think it made sense to my father: religion is irrational enough to explain the Jewish story. Rational categories can’t hold the story.

Israel really was key to providing comfort for my father vicariously, because of course we lived thousands of miles away. Israel was at the center of our family’s life. Hanging on our wall when I was growing up was a bronze engraving of Herzl. Maybe you can see it in the film, in the kitchen. Herzl is the rebbe, he’s the presiding religious figure. In other Borough Park homes, you had ḥasidic rebbes hanging on the wall. In our home, you had a man with a long beard, but without any head covering. Herzl, for my family, was a religious figure.

Jonathan Silver:

Both of you say that Israel was at the center of the moral imagination in the Klein household in those years. One of the things that I found fascinating in the film is that you and your father, for all of the burden that he put on your shoulders and for all of the ways in which he induced you to relive his experience and reenact his traumas, nevertheless had very different views, as I can see, of the United States at the time. Your father mentions that when he arrived there was no one more patriotic than him. You express in the film that—whether you have left this attitude behind or parts of it linger, you’ll explain—at the time, twenty-four-year-old Yossi—I’ll refer to you as in the third-person in describing this character in the film—was very frustrated with America and especially, with America’s Jewish establishment.

Yossi Klein Halevi:

Well, those were the formative years of the Soviet Jewry movement. I was, as you know from the film, part of the movement almost from its beginnings. In those early years, before the cause was adopted by the mainstream community and really became, aside from Israel, the major cause of the Jewish organized community, we were very alone. The demonstrations were small. The activists all knew each other. If not personally, we all knew each other by name. We knew who the guy out on the west coast was. We knew who the person in Cleveland was.

I’m speaking about the mid to late 60s. Then of course, there was the Jewish Defense League, and the Jewish establishment in those years was also very different than it is today. The Jewish establishment was much less secure, both in its Jewishness and in its Americanness. It was more hesitant. Today, to my mind, the Jewish establishment are the good guys. Maybe that’s partly a function of age, but it’s not only me who’s changed.

I think that the American Jewish Community has matured. You didn’t have an AIPAC in those years, or whatever you had of APAC was so small. The notion of 20,000 Jews gathering for a policy conference would have been absurd. The Soviet Jewry movement eventually, I think, played a key role in empowering the Jewish community. I’ve certainly made my peace with American Jewry, even though I’m desperately worried about some of the trends that I see happening in the Jewish community, especially the return of organized Jewish anti-Zionism, which is something that in my generation we thought was over.

The Bund, the American Council for Judaism—which was the radical anti-Zionist wing of the Reform movement in the 1940s—these movements disappeared. The Bund was destroyed; it didn’t survive the Shoah. Seeing organized Jewish anti-Zionism returning in America today leaves me very worried about the future of the liberal Jewish community. I’m deeply connected to American Jewry, and to the American Jewish mainstream, in a way that I wasn’t when I lived there. By extension, I’m much more connected to Americanness as an Israeli than I was growing up in America. I grew up with this feeling that I’m a surrogate Israeli. I’m just waiting for that moment when I’ll be able to finally leave and join what I considered to be Jewish history. That’s where Jewish history was happening and everywhere else was a footnote. Now, I still think that Israel is the center—

Jonathan Silver:

At the time, Yossi, you expressed it somewhat differently. I want to delve into this because it opens up into the psychology of you in your twenties. In the film, your emphasis is not on aliyah. In the film, it’s a different shoe that you’re waiting to hear drop. You are waiting for the Nazis who are around every corner to pull off their masks and reveal themselves. The threats that were manifest to the Jews of Europe were just lurking under the surface of the Jews of America.

The image that you paint so vividly there is, by contrast with the assimilationist tendencies of the mainstream Jewish community, of a Borough Park uprising [akin to that of the Warsaw Ghetto], and planning how the defense league will protect the shops and your neighbors when inevitably the attacks start to descend upon the Jews. In a way, that was Jewish history as you understood it at the time.

Yossi Klein Halevi:

It’s interesting, because if you look at that sensibility through the lens of what’s happening today in America, there are many Jews who would say, “Well, this crazy kid was actually right.” I don’t think so. I don’t minimize the threat to Jewish life of the radical right. But I personally see a greater threat to American Jewry coming from the left, coming from the anti-Zionist left, for two reasons. The anti-Zionist left is trying to destroy the credibility of our story, of our modern Jewish story: our recovery from the Shoah, which is Israel, which is American Jewish power, political clout. The attempt to criminalize Israel and to de-legitimize American Jewish power is really coming mostly from the left. The second threat is that the left, the anti-Zionist left, is restoring what I would call the conditionality of Jewish acceptance in America.

One of the great achievements, maybe the greatest achievement of American Jewry since I moved to Israel in 1982 has come about over the course of two generations. What I’ve noticed as I would come back for visits to America is that young Jews were feeling completely at home without being self-conscious. Previously there was always a sense of Jews being at home in America, but there was a sense of conditionality. The conditionality disappeared, I think, for the mainstream Jewish community. It’s the anti-Zionist left that’s bringing conditionality back; you can be accepted into progressive spaces, provided—here’s the condition—that you renounce Zionism. I actually see the far left, the anti-Zionist left, as a much greater threat. There are Nazis now murdering Jews in synagogues. That’s something that would not have surprised me 50 years ago. I don’t see that as proof that America is no different than any other exile. I think America is different. Even with the rise of anti-Semitism, America is still different.

Jonathan Silver:

To the point about America feeling both at home and at home conditionally, our friend Rabbi Meir Soloveichik tells a story from the George Washington administration. We tend to think about President Washington’s famous letter to the Jews at the Newport synagogue. Many religious communities wrote to President Washington; the Catholics sent him a letter and the Baptists sent him a letter, and different Protestant confessions sent President Washington letters. The Jews sent three letters, and President Washington responded to each of them differently, so anxious were these different communities to try to establish themselves and be at home in the United States. It tells us something about the enduring attitude toward the United States. Here, you come to suggest that actually the establishment of Israel, and maybe especially the Six-Day War, counterintuitively allowed Jews in America to feel more at home in the United States.

Yossi Klein Halevi:

Israel, for my generation, played an indispensable role in helping us feel more at home in America. Take the Soviet Jewry movement. The fact that the Jewish community challenged Richard Nixon and Henry Kissinger over the Jackson-Vanik amendment in 1974, [which conditioned trade with the USSR on the easing of restrictions on Soviet Jewry and other human-rights issues], was something that previous generations of American Jews would never have done. You don’t go against White House foreign policy. I think that that was a direct result of the psychological empowerment from Israel.

Look, I saw it happen literally overnight during the Six-Day War. America fell in love with Israel. America discovered Israel. The special relationship between America and Israel didn’t begin because of the Holocaust. It began because of Jewish power, because of the Six-Day War. In fact, the Holocaust did not have, I don’t think, a particularly strong impact on the America that I knew growing up. The Holocaust was not really part of the public culture until the late 70s really. What was very much part of the public culture in terms of the Jews was Israel. The peak moment, of course, in this relationship was the Entebbe rescue happening on the American bicentennial. America pivoted, and it was an extraordinary thing to watch, to see how the bicentennial celebrations instantly shifted to a celebration of Israeli heroism.

Now, it’s not quite playing out that way for this generation. It’s a different America. The America of today, or at least blue-state America, no longer admires that kind of self-reliance. There’s the victim-as-hero, which is not at all a traditional American notion. What America loved about the Jews, what America loved about Israel, the old America, the America that I grew up in, which I didn’t appreciate at the time—I appreciate it now in retrospect—is that we refused to play the role of victim and we rejected self-pity, and we became victors, victors of our own story. That’s what America loved about the Jews. Again, that’s changing.

Jonathan Silver:

Yossi, I want to focus on the element in the film that has to do with the perpetuation of a story. We’ve been talking up to now about how that story points toward Israel in this case. The story of course, doesn’t start with Israel. It starts a very long time ago. The immediate moment in the story that we focus on is the transmission of your father’s experience in Europe to his son’s shoulders in Brooklyn. It’s obvious, watching you in your twenties, that young Yossi is heavily burdened by that experience, but you at the same time somehow have to honor it. I think that you genuinely do it. You express many times that you loved your father and looked up to him and admired him. There’s never any scintilla of dishonoring him. That’s not who you were, or are. But you also had to become your own man, and I want you to talk about that.

Yossi Klein Halevi:

Part of my process of growing up was realizing the gap between my Jewish experience and my father’s. I grew up in the freest diaspora Jews had ever known, with the state of Israel a plane ride away. The gap between my father’s experience and mine was so vast that I realized there was something perverse about trying to vicariously inhabit his experience. Now, in defense of the young person that I was, I was trying to honor what I thought was my father’s intention, which was to turn me into a vicarious contemporary of his. My father wanted me to be his partner.

Jonathan Silver:

I mean, you described that you even inhabited his dreams, that Nazis were chasing you on the boardwalk at Coney Island.

Yossi Klein Halevi:

Yes. Today, I’m not sure that I was right to think so, but I certainly thought growing up that my father wanted me to inhabit his nightmares. I don’t think that was his intention, but that was certainly the consequence. Thinking a lot about the Holocaust as history, because part of my maturation process, was learning to relate to the Holocaust as history.

Jonathan Silver:

You mean you relate to it as history, as opposed to as inherited family experience?

Yossi Klein Halevi:

As opposed to an open wound. As inherited family experience, it’s always there. I had this experience last Shavuot, just two months ago, where I suddenly made a connection, which should have been obvious to me all these years. I’ve always had a hard time studying, learning Torah, Talmud. It never came easy to me. To this day, I have an ambivalent relationship with Torah study. I’m not one of those learners. It’s just not really part of my Jewish practice. On Shavuot, I finally realized where that comes from: I’m named after my grandfather who was killed in Auschwitz on Shavuot. The train from my father’s town arrived in Auschwitz on the eve Shavuot. Most of the Jews of his town were killed that night. For me, growing up, we always lit a yahrzeit candle, a memorial candle, for my father’s parents on Shavuot. Shavuot was the time of mourning for us. It wasn’t the time of the joyful receiving of the Torah.

I thought of a line from a poem by Jacob Glatstein, who was from Lublin. He wrote the following, “In Sinai, we accepted the Torah, and in Lublin, we gave it back.” I always loved that. I always loved that poem. On Shavuot, I finally understood why I connected so deeply to it. Because Shavuot in my family—you were talking about a family’s experience—was built into my inherited family experience as the day of the anti-revelation. It’s the revelation, not of God’s presence, but of God’s absence.

Look, the Torah is the Torah. It looms over all of us. The fact that learning does not come naturally for me—it’s much easier for me by far to study history than it is to study Torah—there’s something in me that resists it, and I finally made the connection. What I’m trying to say, Jon, is that the inherited family experience of the Shoah remains. It’s something that I’m unpacking, and I will continue to unpack for the rest of my life.

Jonathan Silver:

The issue is that, as a people, we have to figure out a way to relate to the catastrophic mid-20th-century events of Europe that relies on more than inherited family memories. Because as the years go on, those are fraying. At the end of the film, the last sequences of the film show you at the 1981 conference in Israel that brought Jewish Holocaust survivors together. At that time, you were lamenting that survivors were dying. You actually said at the time that you feared for a future in which that would be so. That that witness would not be palpably felt in Jewish communities. All the more so now, 40 years later.

Yossi Klein Halevi:

We’re there now. It’s interesting that survivors, in my experience, either died relatively young, like my father, or lived to their nineties. Real survivors have played it out. It’s over now, the generation is gone. In thirteen years, no, eleven years from now, in 2033, we’re going to be marking the centenary of the Nazi rise to power. It’s history. It’s over. Now, we really need to be thinking: what is the core of that memory that we need to transmit collectively? More and more, for me, it’s not just the memory of the destruction, but it’s the memory of the immediate post-war years and how the Jewish people recovered.

The experience of the DP camps, the displaced-persons camps, is one of the greatest stories I think of Jewish history. It’s been almost completely forgotten. The memory that we have of the post-war years are of the refugee boats trying to run the British blockade, which was the most dramatic expression of the survivor’s response. Look at the DP camps, look at the societies, the Jewish societies, that they created. And these were people in their twenties and early thirties. There were no old survivors. They were all young people, and they created these extraordinarily rich Jewish communities.

There were something like 80 Jewish newspapers being published in Germany between 1945 and 1949; the educational system that was created; the ways in which the survivor communities became Zionist. There were only two ideological streams that took root in the DP camps. One was Zionism, the other was ultra-Orthodoxy. The overwhelming majority were Zionist. Interestingly, the ultra-Orthodox in the DP camps were not anti-Zionist. When you study the DP camps, that, for me, is really the story we need to tell. How did we move from the lowest point in our history, which was 1945, to what I think is the peak moment of Jewish history, which is today? How did we do it?

I think a lot about the two flags on the bimah of American synagogues. That was something that I took for granted growing up as a cliché. It’s something which, unfortunately, we can’t really take for granted today because of a growing distancing from Israel in certain parts of the Jewish community. The extraordinary intuition of the American Jewish community in the 40s and 50s, to place these two flags on the bimah, to sacralize these symbols, because they understood that these were the symbols of the Jewish people’s pushback against the Holocaust. These two flags represented the way in which we overcame the Shoah.

When I think about what we’re going to carry into the future, what I want us to remember is not just Egypt, but the exodus from Egypt. If you look at the Torah, there’s a lot more space devoted to the Exodus than there is to the slavery. I think there’s an imbalance in the way we remember the 40s, and I think we need to shift it. Of course, the Shoah is a foundation for this story. But we need to shift the emphasis educationally, even in terms of our commemoration, away from seeing ourselves as the people that went through the Shoah and more as the people that overcame the Shoah.

Jonathan Silver:

Well, I think that really is the structure of even this film. This film as an early document in that reorientation. We, of course, do learn the story of your father’s experience. Then after the first fifteen minutes, we try to situate ourselves after his experience, and then in the experience of his children and the future they point towards. Your father had two children, and even at that time in the film we see your sister, who’s married and telling us that she’s expecting a child, on the one hand, and we see your movement from the United States to Israel on the other. We see two ways of moving toward a future, a Jewish future.

Let me ask a final question, which to me hints at one of the strategies of survival that I think we can learn from this generation’s experience, which is: why is the film called Kaddish? There is something about historical perpetuation and Jewish religious observance that has helped us endure.

Yossi Klein Halevi:

I think it’s called Kaddish because kaddish is, counterintuitively, a prayer of praise. There’s something remorseless in the Jewish insistence on life, to the extent that the tradition forces the mourner to stand up publicly every day for eleven months and praise God. That’s a really strange move, if you think about it. The comfort that the tradition is offering is a very hard comfort, by forcing the mourner into a posture of praise when that’s not where you want to be. It’s forcing you into this contortion of praise.

Eventually, you grow into the praise, which of course is the wisdom of ritual. Judaism insists on the doing more than the believing. My father is certainly an example of that. My father was an observant Jew because of my mother’s coercion. My father was an observant Jew for years before he actually returned to faith. There’s something about the doing that conditions you, and there’s something in that hard act, that hard demand of the tradition, that the mourner has to become the public praiser of God, a role which you eventually grow into it as the months go on. We all know that experience or will know that experience. Time does its work, but so does the incessant ritual of praise. I think in the end, that’s really what the film is about. The film is a song of praise to the survivors and to who we are as a people today. That’s my takeaway from this 40 or so years later.

More about: History & Ideas, Holocaust, Jewish identity, Mosaic Video Events