The launch in 2015 of the online Arabic-Hebrew dictionary—a massive, fully searchable database complete with notes, examples, and expressions drawn from many historical layers of the Arabic language—capped many years of dedicated labor by Menahem Milson, professor of Arabic language and literature emeritus at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. In the essay below, adapted from remarks delivered on the 90th anniversary of the university’s Institute of Asian and African Studies, Milson reflects on the opening stages of his lifelong involvement with the language.

The attraction was evident from a very early age. In 1936, when I was about three, a scandalized neighbor informed my mother that her darling son had been overheard saying words that did not bear repeating. Evidently, during a quarrel with the neighbor’s son, I’d uttered phrases in colloquial Arabic containing, among others, the words for mother, father, and religion. Without going into further detail, suffice it to observe that, for the purpose of cursing, many Hebrew-speaking Israelis resort to certain Arabic formulations in which all three words figure prominently.

Actually, aside from such offense-giving loan words, I didn’t hear a great deal of Arabic in my childhood, but what little I did hear never failed to intrigue and entice me. Not far from where we lived—the neighborhood of Bat Galim in Haifa—lay the fishing village of Tel al-Samak, whose inhabitants were Christian Arabs of the Greek Catholic persuasion. Every morning the fishermen would come to Bat Galim with their catch and, with me in tow, my mother, who was from Tiberias and had learned Arabic as a child even before she knew Hebrew, would converse with them and interpret for the neighborhood’s Jewish housewives.

Child though I was, I was also aware that Arabic was similar to Hebrew—and that this similarity was natural. From my grandmother’s biblical bedtime stories I learned about Abraham, who, after shattering the idols in his father’s store, came to the land of Israel and fathered two sons, Ishmael and Isaac. We were the descendants of Isaac; the Arabs, of Ishmael. The Arabs were therefore not only our neighbors but also our family members, our cousins.

In this conviction I was not alone. To the contrary, I shared it with many members of my generation and, I have reason to believe, with most young people growing up in the land of Israel in the decades between the first Zionist settlements in the 1880s and the establishment of the state in 1948.

I refer to our sense of affinity with the local Arabs, a longing for greater closeness with them and a sorrow over the breach between us. The Zionist desire to lay down roots in the land of the Bible and to live there in peace, “everyone under his vine and fig tree, [with] none to make him afraid” (Micah 4:4), went hand in hand with a desire to draw near to the Arabs, real-life exemplars residing under their own vines and fig trees.

That desire was reflected in many works of visual art, including the paintings of Ephraim Lilien, Reuven Rubin, Arieh Lubin, Nahum Gutman, and others, and especially in Gutman’s illustrations for the series Torah for Children from which we learned Bible stories at seven and eight. In these illustrations, it was evident to us that that the Arab peasant girl we could see drawing water at a village pump looked exactly like the biblical Rebecca, just as a Bedouin shepherdess looked exactly like Mother Rachel and a Bedouin tent just like the tent where Abraham welcomed the angels in Genesis 18.

The same sense of affinity informed Hebrew folksongs of the time. The shepherd in the field playing his flute, the flocks scampering down the hillside, the camel trains—all of these images connected us at once with our forefathers in Canaan and with our Arab neighbors and cousins. An example:

At the bubbling spring I made my camels kneel

My sweet maiden promised to water them

A jug of cool water she brought up to us . . . .

A second example, this one by the lyricist and composer Emanuel Zamir and featuring both an exact biblical citation and a couplet in colloquial Arabic:

The ox knows its master,

And the donkey its owner’s manger [Isaiah 1:3].

So don’t be puzzled, my friends,

By this folktale about a tame donkey.

Galu lil-himar: la-wen? [They asked the donkey, “where to?”)

Gal: ya lil-hatab ya lil-eyn [It said, “To bring firewood or fetch water”]

I hasten to add that, despite all this, I was also keenly aware of the conflict between us and the Arabs. These, after all, were the days of the “Events,” the Hebrew name given to the Arab Revolt of 1936-1939. From the latter years of the revolt, when I was five and six, I retain memories of hearing that Arabs were torching fields, throwing bombs, shooting at buses, and the like. Armed gangs were abroad, and the Hebrew songs of the period lamented the victims. The poet Shin Shalom:

Five men set forth a homeland to build, five men

Gunfire suddenly pierced the morning air

Five bodies fell with hammers in hand.

The poet David Shimoni:

In Mount Ephraim and Yokneam,

Two friends set out to help the nation

Upon the fields of Israel two young comrades fell,

Two lone guards.

The conflict was searingly real. We spoke about it at home, where my parents explained that it was the fault of the British, who were fomenting hostility between Arabs and Jews in order to advance their policy of “divide and conquer.” Did my parents truly believe this version, a common refrain in the yishuv? I doubt it; more likely, they wanted to reassure us that the enmity between us and the Arabs was not eternal.

If these were the factors shaping my attitudes toward Arabs and Arabic in early childhood, by September 1946, as an eighth-grade student at Haifa’s Reali School, I had begun learning the language formally. The school’s founder and principal, Arthur Biram (known as the Old Man of the Reali), assigned great importance to this subject. In addition to practical considerations—the need to acquire familiarity with the language of our neighbors—he believed that knowledge of Arabic would strengthen and consolidate our mastery of Hebrew (the same way that Latin forms, or used to form, a basis for the study of modern European languages), and would also facilitate the study of Arabic-Jewish culture.

With this in mind, Biram encouraged his Arabic teachers to compose their own textbooks, published by the school itself, as well as a special Reali edition of a reader edited by Avinoam Yellin and Levy Billig—both of whom, by tragic and ironic coincidence, were murdered by Arabs during the Arab Revolt.

Alas, despite our principal’s great esteem for the Arabic language, his students did not take the subject very seriously, and the authors of the two textbooks—Eliyahu Habuba, a Jew from Damascus who wrote a two-part work for beginners, and Meir Plessner, a German Jew, who composed a primer of Arabic grammar—were the butts of constant jokes. By 1946, when I began my studies, Plessner had moved to Jerusalem and Habuba was teaching a different part of the eighth grade.

By happy contrast, my own group was fortunate to have Meir Kister, a new instructor who, within a few years, would become internationally known as the leading authority on early Islam. He immediately launched us into literary (that is, standard or classical) Arabic, with considerable emphasis on correct vocalization. By the second year we were already required to write short compositions in the language. Luckily, toward the end of the first year I’d received from my aunt the newly-published Arabic-Hebrew dictionary by David Neustadt (who later changed his family name to Ayalon) and Pesah Schusser (later Shinar), which put me at a decided advantage over most of my classmates.

In the spring of 1950, toward the close of our fourth and final year of study, Kister began preparing us for colloquial Arabic—a very different beast from its classical counterpart. During the summer vacation, we were to divide up into groups of two or three and spend several weeks in an Arab village to learn the language in its native environment. In preparation, we were taught the elementary rules for negotiating the shift from written to spoken Arabic, and Kister also advised us to buy a spoken-Arabic textbook to learn the verbal inflections and, when we had a free period in school, to improve our comprehension by sitting in on trials being conducted in Arabic at the nearby courthouse.

And so, in July 1950, my classmate Shaul Shaked (whose research on Iranian civilization and Judeo-Persian would later win him the Israel Prize) and I traveled to Umm al-Fahm, at the time the largest Arab village in Israel, and headed straight for the school. We’d arrived on the last day of classes, just before summer vacation, but we managed to meet a few teachers. Later we would encounter them frequently at the local café, where we also became acquainted with other regulars, from small shopkeepers to the local representative of the Communist party. Our mission was to speak, so speak we did—mainly on topics for which (thanks to words picked up from the newspaper), we possessed the requisite vocabulary, like capitalism and Communism, or the criminal exploits of Umm al-Fahm residents whose trials we had attended in Haifa.

Sheikh Tawfiq Asliya, then the vice-principal of the school and later the head of the sharia court in Israel, befriended us. When we told him of our desire to learn to recite the Quran with the correct cantillation (tajwid), he introduced us to his best student: a nice boy, two years our junior, but basically uninterested in the assignment. Or perhaps we ourselves lacked the necessary persistence; in any case, the enterprise was soon abandoned.

Fifteen years later, when I was teaching in the newly-founded Arabic department in Haifa, a student of about thirty introduced himself as the writer and journalist Mahmoud ‘Abbasi and assured me that we had already met. He turned out to be the selfsame star pupil of Umm al-Fahm; in subsequent years he would complete a Ph.D. under the twin supervision of my late colleague Shmuel Moreh and myself.

I returned from Umm al-Fahm aware that my command of spoken Arabic was still limited but confident that I knew enough to make myself understood. And this may be a good point to pause and consider a set of questions that preoccupy anyone studying or thinking about studying Arabic: namely, which Arabic, classical or spoken? Or perhaps both? And if both, in which order?

The basic fact here is that the differences between the two are so significant as to lead the linguist Charles Ferguson to characterize the situation as one of diglossia (two distinct types of the same language used within the same community). Schools cannot teach everything, and therefore the decision must be one or the other: either the basics of the classical tongue, used in literature and in media throughout the Arab world, or the colloquial language—which, since there is no universal form, comes down to the particular dialect spoken in the region of the Arab world where one happens to live.

The problem is not only that the gulf between classical Arabic and each of the colloquial dialects is considerable. That difference is compounded by the discrepancy in their status. Fusha (classical Arabic or, literally, “the eloquent language”) embodies the Arab cultural heritage and identity and therefore enjoys prestige; amiyya (colloquial Arabic or, literally, “vulgar” speech) has none. An anecdote may serve as an illustratation. Thirty years ago, the education committee of the Knesset invited me to a discussion on the teaching of Arabic. The chairman, Shaul Yahalom of the National Religious party, pointedly complained: “Why do Israeli schools teach classical rather than spoken Arabic?” Tawfiq Toubi, an Arab Knesset member of the Communist party, promptly offered a rejoinder: “It’s good that they teach classical Arabic, because Jewish students should be familiar with our culture.”

Some have nevertheless asked why Arabic can’t be taught in the same sequence in which an Arab child learns his or her native tongue—that is, first the spoken dialect and then the written. But a non-speaker of Arabic, even at a young age, is at a severe disadvantage relative to an Arab baby naturally acquiring his parents’ native tongue. And that’s not the only impediment. Children all over the Arab world undergo their own crisis when they enter first grade and have to learn a new form of their native tongue. Why reproduce the difficulty experienced by these children, and why add it to the difficulties already faced by someone of any age encountering the language for the first time?

To me, and I say this as a comfortable speaker of colloquial Arabic, it’s obvious that the correct answer is to build a foundation in classical Arabic before moving on to the spoken dialect.

In the fall of 1950 I began studying at the Hebrew University’s Institute of Oriental Studies, where I would eventually earn my BA in Arabic language and literature. Back then the university still occupied a building in the center of Jerusalem; a separate two-story structure housed the institute, which lacked an office but boasted a reading room grandly presided over by Meir Plessner (formerly of the Reali school). It was there that Professors David Baneth and Shlomo Dov Goitein, renowned experts on Islamic history and Arabic literature, conducted their seminars.

In constant demand, the reading room held the only copies of the indispensable dictionaries, not only the Arabic-Hebrew one by Ayalon-Shinar (formerly Neustadt-Schusser), which, thanks to my aunt, I already owned, but also the almost canonical Arabic-English dictionary by J.G. Hava, as well as the Arabic-Arabic Al-Munjid, the great 14th-century Lisan al-Arab (“The Arabic Tongue”) by ibn Manzur, and Edward William Lane’s late-19th-century Arabic-English Lexicon. A fellow student had the singular fortune of owning a copy of J.G. Hava, and I regularly spent nights in his room preparing for Baneth’s tutorial.

Six years later, I arrived with my wife Arnona to begin graduate studies at Harvard under the great Orientalist H.A.R. Gibb. Our time in Cambridge came to an end in the early 1960s, at which point, returning to Israel with my Ph.D. in Oriental Studies in hand, I took up a teaching position at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, where I would remain for many fruitful decades to come. But since by this point my recitation has exceeded the temporal bounds of “My Early Life with Arabic,” let me conclude by recounting an unforgettable moment at which, just as when I was denounced by a shocked neighbor at age three—but in a very different way—the Arabic language would once more play a highly dramatic role in my personal life.

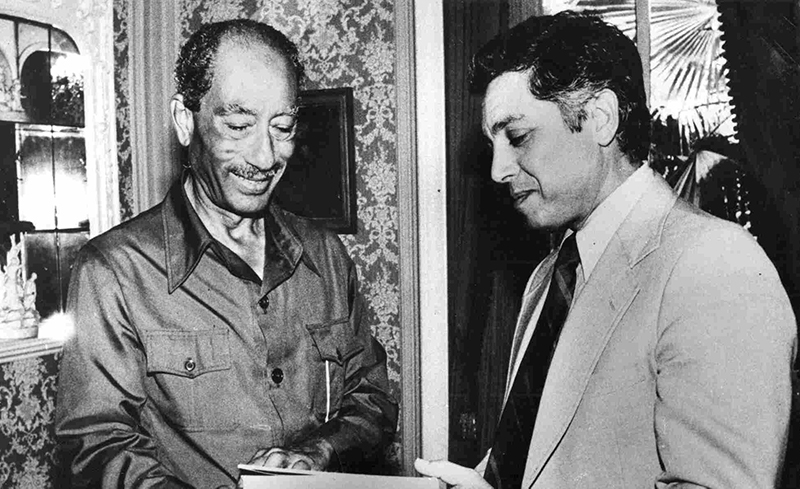

Just over 40 years ago, I was appointed by the Israeli government to serve as aide and interpreter for Egyptian President Anwar Sadat during his historic visit to Israel. I was informed about the appointment three days prior to Sadat’s arrival on November 19, 1977. Hastily contacting the IDF ceremony-and-protocol office, I asked which Arabic formula was used by troops and dignitaries to greet the president, himself a former army officer, at Egyptian military parades. The question drew a blank. Nor was the Egyptian desk at the Military Intelligence Directory any more helpful, and in any case they had other problems to worry about.

Thrown back on my own resources for a way of introducing myself, I devised a sentence in—of course—classical Arabic and committed it to memory. On the evening of Sadat’s arrival, I stood beside Israeli President Ephraim Katzir and Prime Minister Menachem Begin to greet our guest as he descended from his plane. After gravely shaking hands with Israel’s president and prime minister, Sadat turned to me. Dressed in my uniform as a colonel in the IDF, I saluted him, and said:

سيدي الرئيس، أتشرف بأن أمثُلَ بين يديكم بصفتي ياورًا لكم خلال زيارتكم في بلادنا، سيدي الرئيس

(“Mr. President, I am honored to stand before you as your aide-de-camp for the duration of your visit in Israel. Mr. President!”)

Sadat, surprised, threw up his hands and responded, in English, “Bravo!”

More about: Anwar Sadat, Arabic, Arts & Culture, Israel & Zionism