“His Majesty’s Government view with favor the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people.” This is the operative sentence in the Balfour Declaration, issued 103 years ago on November 2 by British Foreign Secretary Lord Arthur James Balfour on behalf of the British government, and transmitted by Balfour to Lord Walter Rothschild for passing along to the British Zionist Federation.

In 2017, on the centenary of the declaration, the anti-Zionist Oxford historian Avi Shlaim described it, more than once, as “a classic colonial document.” No doubt many today are inclined to see it the same way. And indeed it does have some of the external trappings of a “classic colonial document,” addressed as it was by one lord (Balfour) to another (Rothschild) and delivered, one can easily imagine, by a white-gloved emissary from the Foreign Office to the Rothschild palace in an envelope to be presented to the recipient on a silver platter.

Another, similar hint of imperial presumption can be detected in the way the declaration appears to dispose of a territory, Palestine, that Britain didn’t even possess. After all, as Shlaim correctly notes, this was still the “colonial era,” and over the course of World War I the British did author other “classic colonial documents” relating to the future disposition of the Middle East.

But was the Balfour Declaration really such a document? To answer that question, we should compare it with those other British wartime documents.

An earlier one was the 1916 Sykes-Picot accord: a secret treaty between two powers, Britain and France, later extended to Russia and Italy, that anticipated a partition of the Asiatic provinces of the Ottoman empire. It even included a map, with straight lines and colored zones, which the British diplomat Sykes and the French diplomat Picot both signed, dividing the region among the Allied powers. Most notably, it gave Syria and Lebanon to France, and Mesopotamia to Britain.

Sykes-Picot belonged squarely to the long tradition of European powers secretly carving up non-European territory to shore up their own balance of power. Even North America had been subject to this practice. Thus, it was by secret treaties that France deeded the Mississippi Valley (“Louisiana”) to Spain in 1762, and Spain ceded it back to France in 1800.

Then there was that other secret set of commitments, the 1915 Hussein-McMahon correspondence, by which Britain promised territory and recognition to the Sharif Hussein of Mecca in return for his leading a revolt (the famed “Arab Revolt” assisted by T.E. Lawrence) against his Ottoman suzerain. Later claims to the effect that the British had promised Palestine to the Arabs rested on this correspondence.

Anyone familiar with the history of colonialism will immediately recognize the Hussein-McMahon template at work in other so-called “treaties” signed in the 18th and 19th centuries with princely states in India and with Native American nations. They all shared these features:

- The making of commitments in a “native” language, like Arabic in the Hussein-McMahon case, with key elements destined to become “lost in translation.”

- The absence of a map and the vague description of geographical boundaries, each of which would be unthinkable in a treaty between European equals.

- The fact that the agreement never went before the highest metropolitan authority but was delegated for negotiation to a local colonial functionary like Sir Henry McMahon, high commissioner in Egypt and previously a career officer in the British Army in India.

This, then, was a “classic colonial document,” of the sort concluded time and again by every European empire with various princes, rajas, emirs, and chiefs in the Americas, in Asia, and in Africa. In the National Museum of the American Indian in Washington, there are many examples displayed under glass. All such agreements were unequal and likely to be broken.

In form, Sykes-Picot could have been done just as easily in 1816 as in 1916, and Hussein-McMahon in 1815 instead of 1915. But those two agreements were also among the last such documents, because by that time they were already going out of style. The Bolsheviks, when they seized power in Russia in 1917, denounced such secret treaties and published the entire stash of them held by the tsars, including the Sykes-Picot agreement. And the Americans weren’t far behind.

The first of President Woodrow Wilson’s wartime Fourteen Points (January 1918) was an insistence on “open covenants of peace openly arrived at, after which there shall be no private international understandings of any kind, but diplomacy shall proceed always frankly and in the public view.” Two years later, this was codified in Article 18 of the League of Nations Covenant: all treaties and engagements by members had to be registered, so that the League Secretariat could publish them. An unregistered engagement wasn’t binding.

Where in this scheme does the Balfour Declaration fit? The first thing to note is obvious: it was an open declaration, not a secret treaty or a correspondence. That is, it conveyed a commitment made in public, not in private. And it was made not to a foreign government, or to a client chieftain, but to an entire people, the Jewish people, mentioned specifically in the declaration.

This last point is lightly obscured by the fact that it was enclosed in a letter addressed by Lord Balfour to Lord Rothschild. But Rothschild was a mere conveyor. Just after the declaration was issued, the Zionist leader Nahum Sokolow quipped that the declaration had been “sent to the Lord [Rothschild] and not to the Jewish people because they had no address, whereas the Lord had a very fine one.”

The Balfour Declaration thus belongs to the new style of public diplomacy, ushered in by the 20th century: the world of “open covenants.” In an earlier time, the British might have given a secret commitment to Sokolow or his associate Chaim Weizmann, to be disseminated privately across the secret Zionist network. But there was no such network. Theodor Herzl had determined from the outset that political Zionism wouldn’t be a secret society but a public association, doing its business in public congresses; and that the Zionists would seek public commitments, because secret ones could be “revoked at any time.” Herzl and Sokolow, both of whom had been journalists, saw public relations as integral to diplomacy. This gave them leverage, allowing them to treat with the powers as near-equals.

In its form, then, the Balfour Declaration can’t possibly be called a “classic colonial document.” It was an open appeal and commitment made to an entire people, who had no obligation to or dependence on Britain, in the hope that in return they would freely give their own support to the Allies’ war effort. In this respect, the Balfour Declaration had no obvious formal parallel, and perhaps no precedent.

But if not in its form, was the declaration perhaps a “classic colonial document” in its sponsorship? Britain, after all, was itself a colonial power at the time—in fact the largest in history, encompassing about a quarter of the world’s population and land mass.

Here we come to the paradox, or the “forgotten truth,” to which I devoted an earlier essay in Mosaic: by 1917, Britain wasn’t the power it had been. From Gallipoli to the Western front, the war had exposed Britain’s weaknesses and vulnerabilities. It needed every ally it could muster.

Yes, the Balfour Declaration looks like a gesture by a powerful empire, and the phrase “His Majesty’s Government view with favor . . .” sounds like an imperial edict, one that, in its own words, had been formally “approved by the cabinet.” But Britain was in no position to issue a unilateral commitment with regard to Palestine or any other Ottoman territory. Any number of dissenting Allies could have scuttled the whole thing: the French, the Italians, certainly the Americans, possibly even the Vatican.

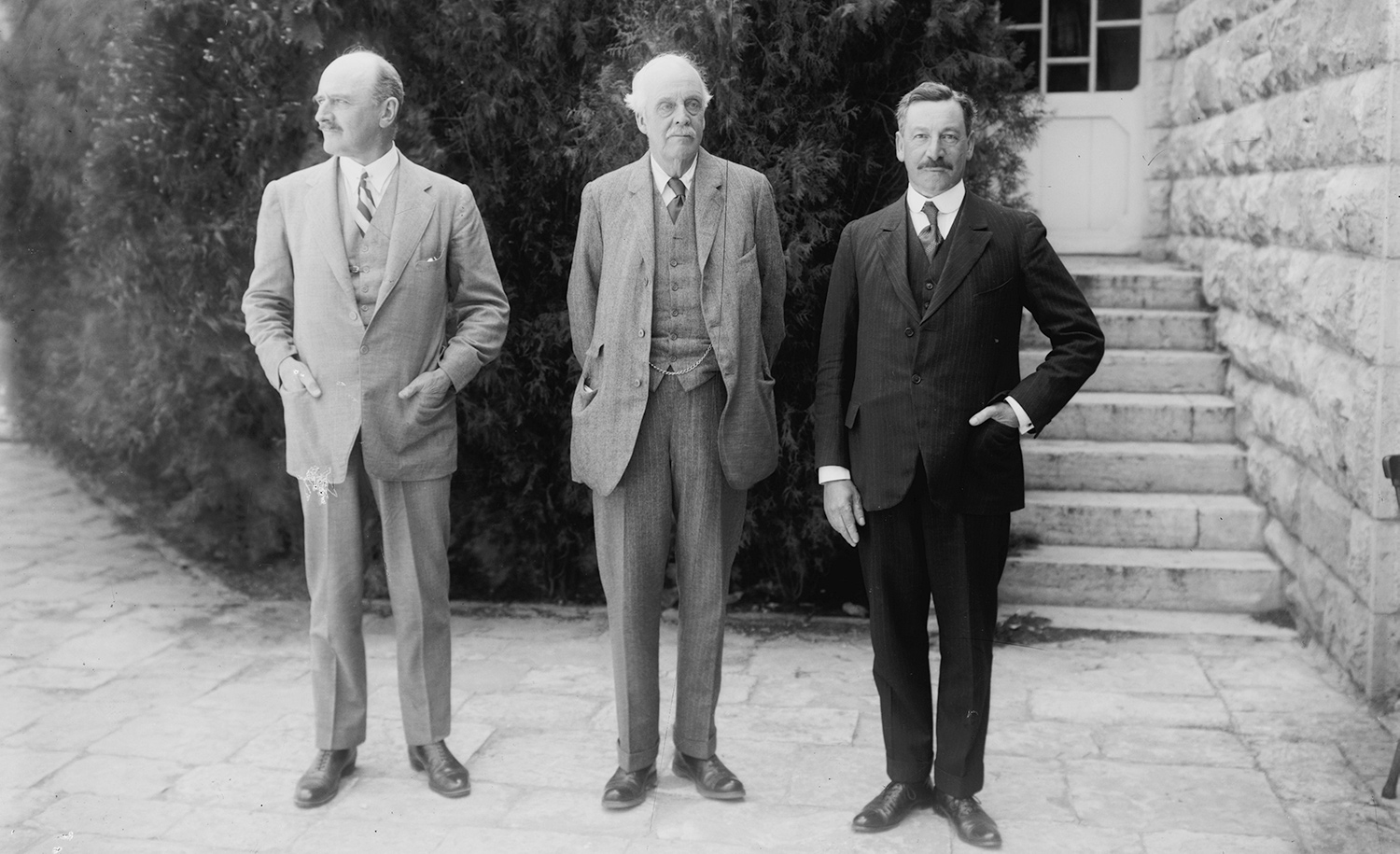

To line up those powers behind the declaration, the British government relied on the Zionists themselves. In my earlier essay I especially emphasized the unremembered role of Sokolow, who went out to Paris and Rome, secured a letter from the French as good as the Balfour Declaration (if not better), and even received a neighborly nod of acquiescence from Pope Benedict XV.

Any declaration also needed the assent of Washington. The United States entered the war in April 1917; after that, it was unthinkable that Britain would issue any public pledge without the agreement of the American president, Woodrow Wilson. To the British cabinet, indeed, issuance of the declaration depended on the fulfillment of a prior condition: “The views of President Wilson should be obtained before any declaration was made . . . as to [its] advisability.” Had Wilson not given the word, the Balfour Declaration would never have been born. He came through—after some hesitation.

Thus, by the time the Balfour Declaration was “approved by the [British] cabinet,” its principles, and in Washington’s case even its text, had been approved by all of Britain’s allies. It was as close as one might come, in 1917, to a UN Security Council resolution.

All of which, of course, made it easier for the Zionists to secure explicit Allied endorsements of the actual declaration right through 1918 and, after the war, in early 1919. In my earlier article, I quoted a passage from Sokolow’s opening remarks to the foreign ministers of all of the Allies at the postwar peace conference in Paris. It is worth repeating:

In the midst of this terrible war, you, as representatives of the Great Powers of Western Europe and America, have issued a declaration which contained the promise to help us, with your goodwill and support, to establish this national center, for whose realization generations have lived and suffered.

In Sokolow’s carefully chosen words, the Balfour Declaration had morphed into the Allied declaration, and no one could contradict him. This Allied consensus also smoothed the way for inclusion of the Balfour Declaration in the League of Nations mandate of Palestine to Britain, thereby making it international law.

In brief: unlike Sykes-Picot, Hussein-McMahon, or any other “classic colonial document,” the Balfour Declaration survived the war not because it harked back to prewar colonialism but because it anticipated the postwar world of national self-determination and international legitimacy. It was also the first in a series of international resolutions on the future of Palestine, followed by the UN Partition Resolution of 1947 and UN Security Council Resolution 242 of 1967.

This brings us to still another question: was the declaration, at least, a “classic colonial document” in its substance?

At one point, the Zionist movement had indeed sought a “classic colonial document”: namely, a charter for a land company. Herzl proposed this in his 1897 manifesto, The Jewish State. There is even a text: a proposed charter for the Jewish-Ottoman Land Company, co-authored by Herzl in 1902 for presentation to Sultan Abdul Hamid II. Herzl may have been inspired by one of the last such charters, given in 1889 by Queen Victoria to the British South Africa Company under Cecil Rhodes. Like any “classic colonial document,” a charter is a contract: the colonial power holds exclusive rights by conquest, which it cedes or leases to the grantee in the form of concessions.

Had Israel come to rest on such a charter, its text would seem no less hopelessly antediluvian. The Balfour Declaration, in contrast, offers support for “a national home for the Jewish people.” This isn’t a concession to shareholders or colonists. It is an acknowledgment that the Jewish people constitute a nation, and thus deserve an equal place among the family of nations in its own homeland.

In the Balfour Declaration, Britain also claimed no rights of its own, instead acknowledging those of the Jewish people. This became clearer in the language of the League of Nations mandate itself, which cited “the historical connection of the Jewish people with Palestine” as “grounds for reconstituting their national home in that country.” Britain may well have wanted Palestine for imperial reasons, but in the new spirit of the times it could no longer invoke the right of conquest. Instead, it would claim to rule as the custodian of the Jewish people.

The Hungarian-Jewish author Arthur Koestler famously wrote that in the declaration, “one nation [Britain] solemnly promised to a second nation [the Jews] the country of a third [the Palestinian Arabs].” So is it, finally, in its approach to the Palestinian Arabs that the Balfour Declaration is a “classic colonial document”?

Koestler’s formula was catchy, but totally misleading. First, as we’ve seen, it wasn’t only one nation making the promise, but the international community circa 1917. Second, the Balfour Declaration didn’t promise the country. It endorsed a “national home” in Palestine, and it wasn’t clear what “national home” meant, except that Jews were in Palestine by right. It also had a tricky limitation, namely, that “nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities.”

The Balfour Declaration didn’t license a state, but it did license Jewish immigration to Palestine. This is why the British colonial officials who later ran Palestine, and who had had past experience running Egypt and India, intensely resented the Balfour Declaration. For them, it wasn’t a “classic colonial document” at all, precisely because it required them to implement a rights-based immigration policy instead of one based exclusively on colonial interests.

Those interests, to colonial officials’ minds, pointed to mollifying the majority Arabs at the expense of the Jews as the most cost-effective way to dominate the country. Thus, the various White Papers issued by London during the mandate invoked Arab “civil rights” in order to limit Jewish immigration, with the result that, in the quarter-century of the mandate, including the desperate years of the Holocaust, fewer than 500,000 Jews arrived from Europe. This constituted about 3 percent of the world Jewish population.

The Palestinian historian Rashid Khalidi would famously denounce the mandate as an “iron cage” for the Palestinian Arabs. But it was also a cage for the Jews, whose numbers the British worked to keep below a third of the population. As a consequence, by 1939, the Zionists had come to see the Balfour Declaration as a promise never kept. It wouldn’t be until November 1967 that the state of Israel even thought to commemorate its issuance.

In sum, the Balfour Declaration isn’t a “classic colonial document” at all. The attempt to cast it as such is clearly part of the political campaign to depict Zionism itself as a species of settler-colonialism. That claim is another issue. But those who invoke the Balfour Declaration as proof for it display either their ignorance of the declaration’s nature or a deliberate and malicious distortion of both its form and its content.

More about: Balfour Declaration, Israel & Zionism, Israeli history