For those of us who had the misfortune to miss the sixties, this last year in Israel has been a blast. Our resentment at having been born too late to rise up in groovy duds and effect earth-shattering social and political change while high on mushrooms naturally leads us to appreciate any civil insurrection in the name of genuine ideals, let alone one carried out by many of Israel’s best and brightest. It also leads us to remind those on the right who bellyache about the “blackmail of an elected government by an elitist minority” that during our childhood an American administration ushered in by a clear majority that proceeded to escalate the Vietnam war was forced to terminate that “police action” once and for all by a scattering of privileged, upper-class, long-haired hippies in jumpsuits. Democracy does not end at the ballot box.

Whatever we may think of the massive, ongoing anti-government protests here in Israel—and many of us, the present writer included, see them as more of an attack on the democratic process than a defense thereof—there is no denying that they have forced an entire society to stop and ponder the most substantive issues related to the nature and future of this still-fledgling polity. Israelis from all walks of life, even those who seldom debate subjects more abstract than the optimal head-height of a properly poured Heineken, now hold forth vehemently to their co-workers, friends, family members, and even random pedestrians about Hobbes and Locke, Berdichevsky and Ben-Gurion, capitalism, liberalism, Zionism—the works. Most important of all, the increasingly belligerent encounters between left and right, secular and religious, and even to a certain extent Ashkenazi and Sephardi segments of Israeli society that have wracked the country over the preceding months have paradoxically opened up not a few heretofore unused lines of communication that, if we only show ourselves wise enough to take advantage of them properly, may well generate new modi vivendi between the various warring tribes that make up our people.

Hats off, then, to the demonstrators, and a heartfelt hope that they get a good deal of what they want. Again, not because they are necessarily right—this author, like most Israelis, ceased delving into the particulars of the judicial-reform conundrum after hearing a hundred convincing arguments for and another hundred against—but because at each and every one of their numerous events these left-of-center activists have consistently chanted their insistence upon ensuring that Israel remain “a democratic and Jewish state” (m’dinah demokratit v’yehudit). This two-ply refrain is front and center at all of their rallies, sit-ins, roadblocks, strikes, festivals, and building occupations, and is backed up by the presence of gargantuan, hundred-foot-long copies of Israel’s Declaration of Independence, borne aloft by dozens of marchers like a giant crowd-surfer at a rock concert—a document, it should be noted, in which the “Jewish” element upstages the “democratic” element by a ratio of about ten-to-one. We therefore have a right to expect that after they succeed (according to their own lights) in ensuring that Israel remains a democratic regime, it will then be time to do all in their power to ensure that Israel remains a Jewish regime—right? That was and is, after all, the entire point of the Zionist venture—the only reason Israel exists.

In anticipation, then, of that blessed day on which we will all sit down—without rancor and vilification and with a lot of good will and even a modicum of mutual affection—and finally hash out the incomparably essential question of how we might infuse our beloved state of Israel with a Jewish character in a manner that is genuinely acceptable to all parties concerned, I offer the following modest proposal.

Judaism has a negative dimension and a positive dimension. In the negative category we have all those “Thou shalt nots”: no stealing, no boiling a kid in its mother’s milk, no tattooing, no cross-dressing, etc. In the positive category we have not only the 248 Pentateuchal prescriptions—“Write them on the doorposts of thy house,” “Rise in honor of the elderly,” “Keep the Sabbath day,” “Dwell in a sukkah for seven days”—but the entire, matchlessly rich literary and historical heritage of the Jewish people, that heritage, after all, consisting of a cornucopia of national-cultural content that does not require anyone anywhere to refrain from doing anything.

Now, negative proscriptions unquestionably constitute an essential aspect of Judaism. But regarding many of them the rival camps within our nation will never agree, and indeed: the possibility that a given government might anchor some of them in legislation is the ultimate, screaming nightmare of well over half of the Israeli population, and the casus belli in the name of which they would unquestionably be willing to bring the entire Zionist enterprise crashing to the ground. That is why they are out in the streets in such large numbers, many of them dressed like handmaids from the Netflix series.

The positive element of Judaism, on the other hand—that vast and colorful universe of stories, rituals, customs, holidays, songs, heroes, rites of passage, historical reenactments, intensive learning, etc.—is by nature far less threatening, while at the same time far more effective than its negative counterpart for purposes of cultivating the powerful and enduring connection of Jews to their people and homeland. (Building and dwelling in a sukkah evokes our nation’s journey to the Promised Land, the shakiness of our existence in exile, the sheltering wings of the Divine Presence, the transitory nature of wealth, the aspiration to peace on earth, and more; not cross-dressing evokes . . . not cross-dressing.)

Take Passover as an example. On the one hand, the Torah negatively enjoins: “No leaven may be eaten.” On the other, it positively commands: “For seven days thou shalt eat matzot.” Now, if we place our emphasis on the first clause and—as Israel’s religious parties did just two months ago, in one of the worst cases of bad timing in human history—enact an “anti-leaven law” that authorizes guards at hospital entrances to search the bags of those coming to visit ailing loved ones for contraband crackers, then we will compound the number of Jews eating leavened products on Passover sevenfold and ensure that irate citizens hold protest pizza parties outside of emergency rooms in the middle of the holiday. (The fact that this law was far less intrusive, and far more justified, than Israel’s largely anti-religious press depicted it is beside the point for this purpose.)

If, on the other hand, both government and civil society place their emphasis on the “Thou shalt” and positive aspects of the holiday, by holding huge, outdoor matzah-baking workshops in parks, schools, and malls; by producing itinerant out-of-bondage dramas put on by traveling thespians for audiences across the country; by distributing free pop-up Haggadahs to elementary schools together with mechanical frog-toys that leap hither and thither and yon; by subsidizing group trips to stunningly beautiful Sinai where participants will follow in the wandering footsteps of our ancestors; even by raining down manna candy-bars tied to tiny parachutes from hovering drones onto the heads of Israel’s children—if we take this positive route, not only will we cease frightening, infuriating, and distancing our fellow Jews, we will be privileged to bring them closer, enrich them, interest them, and thereby render a major contribution to the Jewish character of our state and society. The best part of this method is, of course, that everyone is happy. The religious sections of Israeli (and Diaspora) society, whether of the Zionist or ḥaredi variety, are not about to oppose a national pandemic of matzah baking, while even the fiercest secularist at the left-of-Spartacist-League Haaretz newspaper will not take issue with it. Parents from both camps will bring their children at a run to such events, where they will discover that they are not enemies, but brothers and sisters, heirs to a common, beautiful, enjoyable heritage.

Last May, Israel’s most famous young female singer, Noa Kirel, came close to winning the widely watched EuroVision song contest. This was no small feat, given that several hours before her debut Israel had assassinated three commanders of the Islamic Jihad terrorist organization together with (despite the IDF’s best efforts) several of their children. The song itself—an abjectly meaningless concatenation of English syllables vaguely referencing a unicorn and lacking any connection to Israel or Judaism (or anything)—was performed by the starlet while gyrating on the floor rather scantily clad. Ultra-Orthodox MK Moshe Gafni, when asked disingenuously while on the Knesset podium why he did not congratulate Kirel on her achievement, responded by offering to “buy her some clothes.”

Did his comment reflect a sincere inner agony at the prospect of a young Jewess parading her wares for all the world to see? Certainly. Did it help in any way? Punktfarkert—just the opposite. “Disrobing campaigns” popped up on social media like mushrooms after a rainfall in the wake of his unfortunate statement, and thousands of young Israelis voiced their exponentially increasing disgust for Judaism in response. If only MK Gafni and co. would devote as much time, effort, money, and political savvy to the positive side of our tradition as they do to remonstrance.

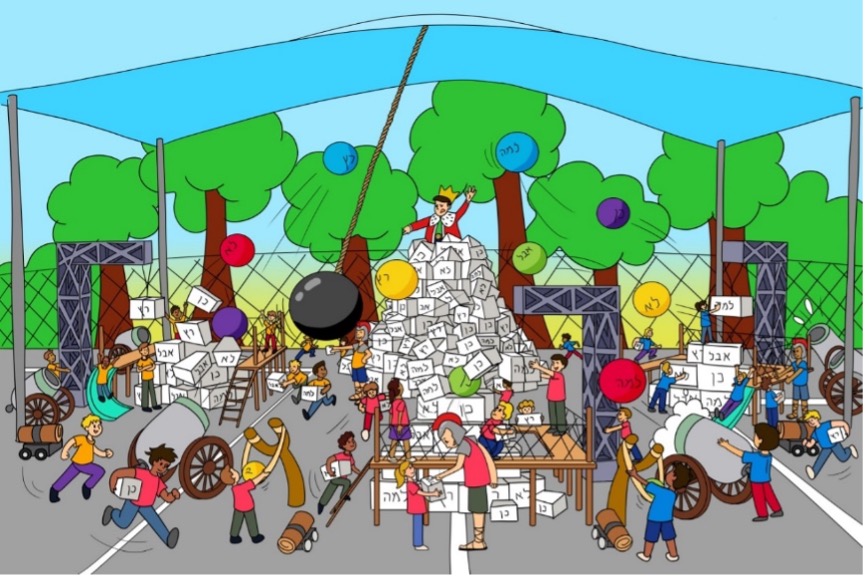

One can pile up examples of such a Judaism of Yes interminably, because the potential is endless: thrice-annual pedestrian pilgrimages to Jerusalem from all parts of the land, with families from hundreds of cities, towns, kibbutzim, and the like encountering their fellow Jews and picnicking, playing sports, studying, listening to lectures, singing, and sleeping under the stars at meeting sites along the way as they gradually converge on the City of David; exciting and inviting Sabbath-welcoming services in suburban fields in the spirit of the Elders of Safed; Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur gatherings (and Tisha b’Av commemorations, and Megillah readings) in the centers of cities for the hundreds of thousands with no place in synagogue and no desire to go there; mammoth menorahs placed atop mountains and skyscrapers throughout the country for the sake of publicizing the Hanukkah miracle; Bible restaurants with scriptural menus and patriarchs for waiters; Pentateuchal playgrounds complete with Noah’s rainbow slides, Mount Sinai climbing walls, Jonah’s whale entrail tunnels, Topple Goliath punching dummies—you get the picture. (The reader will be so kind as to give me one reason why the Jewish state should spend billions of dollars to erect boring, unimaginative, generic playgrounds in a thousand different venues, when for the same money we could be building the above and facilitating in the heads of Israeli children the equation: “Bible = The Most Fun I ever Had!”)

Some of you are guffawing: “It’s a state, not a summer camp!” (Others, especially in the ultra-Orthodox camp, are adducing various undeniably compelling rabbinic admonitions against turning our tradition into buffoonery.) But in truth, there is no subject more serious than this one. The content of our children’s leisure time and entertainment culture will determine, more than any other factor, whether our beloved polity maintains its raison d’être as the national home of a unique and distinct ethno-religious collective, or in other words, whether Israel continues to be a Jewish state. Today, the leisure time and entertainment culture of Israeli children is filled with content almost entirely foreign—non-Jewish, non-Hebrew, and non- and anti- Israeli—making the prospects for such a continuation quite bleak. What exposure most Israeli kids have to Judaism is largely negative, in the form of excruciatingly boring school curricula or what their parents perceive as attempts by the coercive Orthodox to restrict secular citizens’ rights and pursuit of happiness. It should come as no surprise, therefore, that—certain undeniably impressive and encouraging exceptions notwithstanding—the lion’s share of Israelis are busy jettisoning most aspects of Jewish, Hebrew, and Zionist culture in favor of a wholesale adoption of a language, lifestyle, literature, and civilization imported lock, stock, and barrel from across the Atlantic. The vast majority of children in my neighborhood spend Rosh Hashanah and every other Jewish holiday either at the beach listening to Kanye West, at the skatepark listening to Kanye West, or at home on their phones . . . listening to Kanye West. Our ties to our sacred sources, our hallowed tradition, our powerful history, and even our longed-for land are being rapidly severed. It’s as simple as that.

Strange: one would have thought that suffusing and decorating the Jewish national home from Kiryat Shemonah all the way down to Eilat with eye-catching, entertaining, edifying, and animating content from Bible, Talmud, Midrash, Jewish and Zionist history, and the like would be a classic no-brainer, even if just for purposes of attracting massive foreign tourism. One would have thought that turning our incomparably colorful heritage into a plethora of highly enjoyable daily activities for young people would be the obvious Zionist and modern Jewish choice.

Well, think again: with a few notable exceptions, the public and recreational sphere in Israel is virtually bereft of Jewish content, and filled instead to overflowing with American and universalist paraphernalia of every kind, as the Jewish state runs blindly along with the blundering, conformist, worldwide herd in the direction of imminent self-erasure and immersion into the uniform soup of a shallow internationalism. This, instead of standing strong as the people set apart that we have always been, instead of acting like any self-respecting, independent national entity should. The up-and-coming generation in this country (like everywhere else) lives increasingly in global cyberspace and will soon have no reason whatsoever to stay here, and—especially given the pressure exerted by our violently hostile neighbors—every reason to emigrate. TikTok is taking over our children’s lives, and driving them away from their land and their people.

A massive campaign based on a Judaism of Yes, in which we merge the leisure and entertainment culture of Israeli children (and adults) with souped-up, stimulating, affirmative, and non-threatening Jewish content is the only way we will avert this cataclysmic eventuality. We will be helped in this campaign to no end by the myriad parents and teachers across the length and breadth of the country who are searching desperately for a way to pull their children and students out of globalizing cyberspace and back into immanent reality, away from the mesmerizing, paralyzing, enervating, childhood-destroying addiction to screens large and small, and back into the genuine, tangible, sunlit world of nature, play, family, friends, trees, grass, and togetherness.

If the Judaism of Yes is not to remain a pleasant-sounding slogan, it needs nothing less than an army. More specifically, it needs a Jewish-Hebrew-Zionist production company that will assemble the most creative and passionate minds in Israel and abroad for the purpose of mining our tradition in order to create Jewish content too good to refuse: everything from toys to games to trips to Samson Fitness Centers to hit songs to shopping malls to historical reenactments to children’s books to playgrounds—and, yes, even some movies, series, and apps (we must not be full-fledged Luddites).

We will know that we are on the right track when an Israeli citizen cannot walk a single block in his neighborhood without encountering a stimulating evocation of an exciting aspect of Jewish civilization; when Israeli parents can take their children to a biblical restaurant or amusement park, a Jewish jamboree or jungle gym, a midrashic cafe or prophetic pizza parlor; when talking statues of Zionist heroes at municipal crosswalks bring street names to life; when Israeli kindergarteners ride on Balaam’s Ass, run from the Golem of Prague, and build with Tower of Babel blocks; and when Israeli adolescents hum around the house the latest Hebrew music, which the vast majority of them no longer even listen to. (“Let me write the songs of a nation,” exclaimed the Irish revolutionary Daniel O’Connell, “and I don’t much care who writes its laws.” Hebrew music is ten times more important to the future of the state of Israel than judicial reform.)

The enormous amount of Jewish energy, talent, and imagination that has been spent in modern times on creating the leisure and entertainment culture of other nations, must now be redirected toward creating the Jewish people’s leisure and entertainment culture. The positive dimension of our Judaic heritage must be plumbed to its depths, brought to vigorous life, and made into the default option for Israel (and Diaspora) recreation from dawn to dusk.

It is time, therefore, for nothing less than a Judaism of Yes.

More about: Israel & Zionism