I am Nahum. That is my Hebrew name, after my mother’s father, Nahum (Nathan) Berman. He was a scholarly and devout Jew who saw to it that not only his son but also, less commonly, his daughters were well educated in Jewish sources. My mother would recall his saying that if you can’t have an ancestor, be one.

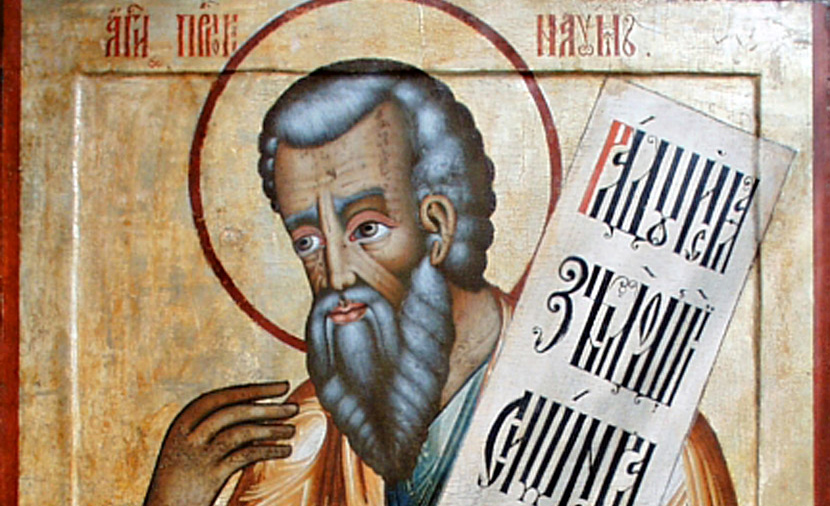

As it happens, Grandpa Nahum and I do share a highly distinguished ancestor: both of us bear the name of one of the ancient Hebrew prophets—if also one of the least known. Inspired by this coincidence, I’ve spent some time reading Nahum’s brief book and investigating his place in the prophetic tradition. The experience has persuaded me that our ancient namesake deserves greater and more sympathetic attention than he has received. I even have a specific suggestion for his rehabilitation.

The ancient Nahum is one of a group usually identified as the “minor” prophets, to distinguish them from the three major figures of Isaiah, Jeremiah, and Ezekiel. The twelve books of the “minors” are all materially shorter than those of the Big Three, in some cases amounting to no more than a handful of verses. The book of Nahum itself consists of a mere 47 verses, divided into three chapters, and takes up two-and-a-half pages in my copy of the Koren Tanakh (Hebrew Bible). By comparison, Jeremiah stands at 1,364 verses in 52 chapters for a total of 69 pages.

Among all fifteen prophets, moreover, Nahum occupies an especially obscure position. Not only does his book fail to provide any of the prophetic readings that follow Torah readings on Sabbaths and holidays, but only a single phrase from it appears anywhere in the Jewish liturgy—and that phrase is a quotation from the book of Exodus. Nor does he receive much notice in rabbinic literature, garnering only eight references in the entire Babylonian Talmud and only 31 in the main compilation of rabbinic midrash (according to a tally in the Anchor Bible edition of his book). Probably the best-known modern-day Jewish study of the prophets, by Abraham Joshua Heschel, contains no entry for him at all in the index. Fortunately, Norman Podhoretz in The Prophets (2002) accords him two thoughtful and deeply appreciative pages.

Nahum has also been largely ignored in Christian worship. He is absent from the readings in the Roman Catholic Sunday Lectionary and likewise from the Revised Common Lectionary used in Protestant worship. He has also been treated with striking hostility by some Christian Bible critics and even suffered calls for his removal from the roll of prophets. In his Anchor edition of Nahum, the late Duane Christensen observes that some of the book’s readers regard it as “ethically and theologically deficient”; he quotes one (non-Jewish) scholar as asking: “Will any of us ever have the courage to admit . . . that the book really is rather a disgrace to the two religious communities of whose canonical Scriptures it forms so unwelcome a part?”

Notwithstanding all this, I would insist that the book of Nahum speaks to us importantly and even urgently. I say this on the basis both of its actual contents and of the simple but telling fact that the compilers of the Hebrew Bible thought highly enough of it to include it in the canon (from where it was then carried over into the Christian Old Testament). Ironically, the claim on our interest laid by this least familiar and often reviled work is connected in part with its relationship to one of the Bible’s most familiar and best-loved books—namely, the book of the prophet Jonah, so greatly honored in Jewish tradition as to be read in full each year on the afternoon of Yom Kippur.

I’ll return to the connection between the two books later on, but for now it suffices to note that both of them are concerned solely with the contest between God and the wicked kingdom of Assyria—which Jonah refers to as Nineveh, the name of its sometime capital city. Before proceeding further, then, it would help to sketch some of that ancient power’s history and character.

The Assyrian empire was centered in what is now northern Iraq but for much of its long history sprawled over present-day Turkey, Egypt, Syria, Jordan, and Saudi Arabia—even extending, at times, into Libya and Cyprus to the west and south, and Iran to the east. In one shape or another, the empire lasted for more than 1,500 years before finally falling to the Babylonians in 612 BCE. The city of Nineveh stood on the Tigris River near modern-day Mosul, Iraq.

Assyria was a militaristic, cruel, exploitative force. Deploying the largest standing army in the ancient world, it ruthlessly invaded neighboring countries, extorted huge tribute from the states it subjugated, and used the plunder to enrich a noble class and undertake further military adventures. Its principal contribution to the development of civilization was the invention of an early form of ethnic cleansing: the wholesale removal of defeated populations from their home territories and their dispersal within the empire, thereby erasing their tribal, ethnic, and religious identities.

Assyria’s relationship to the ancient Israelites was, typically, one of destruction, oppression, and near-extinction. It was the Assyrians who, in approximately 722 BCE, invaded, conquered, and dispersed the northern kingdom of Israel, laying waste to its capital, Samaria, wholly excising the ten northern Israelite tribes from history, and forcing the southern kingdom of Judah into subservience. When, in the final years of the 8th century, the reforming King Hezekiah of Judah sought to loosen the empire’s hold, the Assyrians went to war, devastating the Judean countryside and in 701 laying siege to Jerusalem, the last stronghold of the Jewish people.

But then an astonishing thing—or perhaps, more appropriately, a miracle—happened: the Assyrian army, poised on the brink of success, suddenly fell back, leaving Jerusalem unconquered. According to the account given in three different books of the Bible, a deadly plague had swept the Assyrian ranks, forcing a retreat. For their part, Assyrian sources make no mention of a plague, but it is undisputed that the Assyrian king, Sennacherib, abandoned the siege, thereby permitting Judah to survive for more than another century until it, too, would fall to the Babylonians in 586.

This is one of the great “what-if” moments in all of Western history. Indeed, in The Collected What If? (2001), the historian William McNeil identifies Sennacherib’s failure to take Jerusalem in 701 as “the greatest might-have-been of all military history.” As he points out, had the Assyrians not withdrawn, leaving Jerusalem intact, it is all but certain that the surviving Judeans, too, would have been taken captive, and their cultural and religious identity obliterated. Like the Israelites before them, they would have vanished from history. And then what? A world without biblical Judaism, McNeil plausibly argues, would also be a world without its successors Christianity and Islam—a world “profoundly different in ways we cannot really imagine.”

Instead, the deliverance of Jerusalem and Judah by means (in Jewish belief) of a timely plague had the opposite effect, fortifying the conviction that, despite the crushing loss of the northern kingdom, God had not abandoned His covenant with His chosen people. While the southerners’ fidelity to Jewish belief and practice would exhibit its own ups and downs in the century-plus that remained to their sovereignty—Hezekiah’s successor, Manasseh, was a notorious idolater—religious and national morale during that era revived to the point of later proving strong enough to withstand the huge shocks of the destruction of the Temple and the Babylonian exile.

Enter now Nahum. As is the case with many of the prophets, nothing is known of him beyond what can be inferred from his book. There is even speculation that Nahum was not Nahum—that the name, which in Hebrew connotes comfort or consolation, was a pseudonym chosen to highlight the message the author wished to convey to his contemporaries. It doesn’t help that he’s further identified as “the Elkoshite,” since no one knows for certain where Elkosh was or whether it was a place or a tribe. Nor is there any consensus on exactly when Nahum was active, although it seems clear that it was sometime after the fall of the northern kingdom and while Nineveh still had its boot on Judah’s neck.

But who cares? The search for the “historical Nahum” is not only fruitless but pointless. The book speaks perfectly well for itself.

Nahum’s prophetic message is unambiguous and full-throated: God will execute vengeance on His enemies and the enemies of His chosen people; they will be delivered unto death, obloquy, oblivion; and good riddance to them. A masterpiece of triumphalist rhetoric, the book rings with confidence in the promise of divine redemption and with unalloyed joy at the fall of the oppressor. It is completely devoid of the feature common to the better-known prophetic works: reproach of the Jews themselves for failing to honor their covenant with God, for whoring after strange gods, and for wantonly violating the basic precepts of morality and social justice. In its place, Nahum devotes himself entirely to both describing—in vivid, sometimes vulgar, and sometimes gory language—and unapologetically celebrating the coming downfall at the hands of God of the Israelites’ arch-enemy.

Structurally, the book consists of three distinct but related elements. First, there is an introductory hymn, appropriately called the Psalm of Nahum, which enthusiastically praises the God who “takes vengeance on his adversaries” and who, while “slow to anger,” is “great in power” and “will by no means acquit the wicked”: “they are entangled with thorns, drunken as with their drink; they are devoured as stubble fully dry.” (I take all translations from the Koren Tanakh.)

Next, Nahum turns his attention explicitly to Assyria. God expresses his determination to destroy and eliminate this great power: “Now will I break his yoke from off thee and will burst thy bonds asunder.” “O Judah, keep thy feasts, perform thy vows: for the wicked one shall no more pass through thee.” “For the Lord restores the pride of Jacob, like the pride of Israel.” In a series of vivid images, Nahum forecasts Assyria’s actual demolishment:

The shield of his mighty men is made red, the valiant men are in scarlet.

They stumble in their walk.

She is empty, and void, and waste: and the heart melts, and the knees knock together, and there is trembling in all loins.

And there is a multitude of slain, and a heap of carcasses; and there is no end of corpses.

Finally, on top of this unstinting catalogue of death and ruination, Nahum adds what are usually described as verses of “taunt,” or what I referred to above as the good-riddance part: “Behold, I am against thee, says the Lord of hosts; and I will uncover thy skirts upon thy face, and I will show the nations thy nakedness, and the kingdoms thy shame.”

Here, outdoing all that has gone before, are the book’s last lines:

Thy shepherds slumber, O king of Assyria: thy nobles are at rest: thy people are scattered upon the mountains, and no man gathers them in. There is no healing for thy breach, thy wound is grievous: all that hear the report of thee clap the hands over thee. For upon whom has not thy wickedness passed continually?

Powerful, unforgettable stuff. Why, then, has it been neglected and shunted aside? It is certainly not for any lack of appreciation of the book’s literary merits: those merits are acknowledged even by those who have trouble accepting its substance. Lauding the “vividness and picturesqueness of the prophet’s style,” the Catholic Encyclopedia concludes that “Nahum is a consummate master of his art, and ranks among the most accomplished writers of the Old Testament.” Dale Christensen in the Anchor edition concurs: “In its poetic form, the book of Nahum has no superior within the prophetic literature of the [Hebrew Bible].” In his introduction to the Soncino edition, S.M. Lehrman avers that “The vigor of [Nahum’s] style and the realism of his prophecy . . . set it on the topmost rung of sublime literature.” To the authors of the article on Nahum in the Jewish Encyclopedia, “[t]his compact, pointed, dramatic prophecy has no superior in vivid and rapid movement.” Adding my two cents, I would note that Nahum not only is a master of striking language and diction but displays a precision and focus rare among the prophetic texts. Even his seemingly difficult passages—where, for example, it’s unclear who is speaking to whom—come across as products of conscious literary choice rather than, as in similarly arcane passages elsewhere, the results of inaccurate textual transmission or even authorial lapse.

So it is not for want of literary merit that Nahum is absent from the liturgy. To the contrary, the book’s very force and power—its “blazing heat and pellucid clarity,” in Podhoretz’s apt formulation, the unrivalled intensity and descriptive concreteness with which it presents its case—may more nearly explain its studied neglect. After all, God’s vengefulness and violence toward the enemies of His people—the qualities that Nahum devotes himself wholeheartedly and single-mindedly to extolling—aren’t exactly the biggest crowd-pleasers among the Divinity’s attributes. The fact that Nahum has been shunted aside or worse may in this sense be seen as a perverse compliment to the distinctive power of a work whose theme is one that many have found embarrassing, distasteful, or even repellent.

Even in strictly observant Jewish circles, Nahum’s message inspires resistance. The staunchly Orthodox ArtScroll edition of Nahum, for example, prefers to read the book as, in effect, offering the Assyrians one more chance at repentance: “It was the mission of this prophet to warn the Assyrians that their utter destruction was sure to come if they did not change their wicked ways.” A more palatable and face-saving interpretation, without a doubt—except that, in order to read Nahum in this fashion, one must willfully ignore his straightforward, relentlessly repeated statements that the time for repentance is long past, and divine destruction is both inevitable and at hand.

Much less impelled to equivocate are Nahum’s Christian critics, some of whom, however, have been quick to enlist the book as Exhibit A in the Christian case against Judaism. Thus, the Roman Catholic editors of the Jerusalem Bible, for whom “[t]he book pulsates with the hatred of Israel against the people of Assyria,” proceed forthrightly to condemn its “violent nationalism, where there is no anticipation of the gospel whatsoever, or even of the worldwide outlook of . . . Isaiah.” This critique obviously proceeds in part from the long-held view that with the coming of Jesus, the vengeful “God of the Old Testament” was superseded by the Christian message of love—the message, as one source puts it, that “we should pray for our persecutors, not curse them.” Out of the same scandalized impulse, liturgical reformers at the Second Vatican Council in the early 1960s went so far as to rewrite some of the so-called “imprecatory” psalms that, like Nahum, celebrate divine vengeance, and to delete others altogether from the Catholic psaltery.

And yet that’s not the whole story. Other Christian critics and scholars have raised strong, principled objections to the critics and bowdlerizers. The late Catholic theologian Erich Zenger, in A God of Vengeance? (1995), labels the work of the Vatican II reformers as “an act of magisterial barbarism,” and defends the gelded and deleted texts as “the expression of a longing that evil, and evil people, may not have the last word in history”—words that apply equally to the spirit animating the prophet Nahum. Going still further, J.J.M. Roberts of the Princeton Theological Seminary forcefully rejects the idea that Nahum itself is un-Christian, and turns the argument back on the critics:

One should beware of any bogus morality that dismisses vengeance as both inappropriate to humans and unworthy of God. . . . While the desire to see vengeance done can be twisted and corrupted like any other human desire, it arises out of a sense of justice, and vengeance cannot be discarded without discarding the concern for justice as well. . . . [W]ithout this frightening side . . . , one could misread the portrait of the loving God as that of a passionless, doting, and undemanding dispenser of cheap grace.

This is exceptionally well put, I think, and gets us to the heart of the matter. For one thing, it is useful to recall that the ancient decision to preserve Nahum’s work within the canon of the Hebrew Bible, right alongside the perhaps more immediately appealing “worldwide outlook” of Isaiah and other prophets, itself merits a high level of respect. Pace the Catholic editors of the Jerusalem Bible, the books of the prophets are not there to serve as a dozen “covers” of the same tune. The very variety of the prophetic books reminds us that the God whom the prophets encountered and whose voice they channeled is not reducible to a simple formula. Vengeance is part of His being

This prompts another thought, and one of particular resonance in our era. The divine vengeance praised by Nahum is a power that for him is exercised by God alone, thus preempting—and precluding—such behavior by humans. If, conversely, one believes it is wrong for vengeance to be taken by God—and if a prophet who celebrates His exercise of that power should be purged from the Bible—the certain alternative is that violent and willful men will seize for themselves the right to render and execute judgment in His name. This is just what we are living through at the hands of significant numbers of self-described religious Muslims in the Middle East, Africa, Europe, and even the United States who have committed murder and other atrocities while invoking the name of Allah—and who receive legitimating support and encouragement from at least a portion of their clergy. Many of the worst instances of this behavior are in fact happening in the ancient Assyrian heartland, and “Assyrian” Christians figure prominently among the victims. Properly read, Nahum raises the theological question of whether that is really a preferable alternative to divine vengeance exercised exclusively by the Divinity.

And that brings us back, finally, to the placement of Nahum’s book within the order of the twelve minor prophets and to its connection with Jonah. An ancient tradition evidently positioned the two books together, with Jonah first; that is how they appear in the Septuagint, an early Greek translation of the Bible from a now-lost Hebrew text that long antedates the earliest surviving manuscript of the Tanakh we use today. In today’s ordering, the book of Micah comes between them. But whether cheek-to-cheek or one apart, it is hard to resist the inference that we are expected to encounter the two books—both addressing the divine encounter with Assyria, but with very different messages—in tandem. Reading Nahum in isolation is, I think, untrue to the reason why his book was preserved in the first place.

In Jonah, the reluctant prophet warns Nineveh that divine destruction is only 40 days away. The book then carefully details the acts of repentance undertaken by the alarmed Ninevites: the king himself removes his royal robes, puts on sackcloth, and sits in ashes, ordering his people (and their animals!) to fast, wear sackcloth, and “turn everyone from his evil way, and from the violence that is in their hands.” When God sees “their deeds in that they turned from their evil way,” He relents and spares all.

Nahum, for his part, enlightens us to what is about to befall that same city and kingdom at the hands of that same God—after Nineveh has exploited its divine reprieve to oppress Israel and nearly extinguish it. When one reads Nahum in conjunction with Jonah, and with alertness to the ugly and violent deeds of a Nineveh that has reverted to its pre-Jonah ways, a familiar, even orthodox lesson emerges: repentance by itself, however fully its forms are observed and with whatever momentary sincerity, is not enough to keep God’s favor. Ultimately, if proper ritual behavior isn’t matched by actual good behavior, divine destruction follows. For teaching this lesson, and with such searing clarity, Nahum deserves to be brought in from the cold and to be read and appreciated not in isolation but “among the prophets,” particularly Jonah.

Both books will benefit. For just as Jonah contextualizes and harmonizes Nahum with the prophetic tradition, so Jonah is impoverished and deprived of its full resonance when read in isolation from Nahum. The combined power of both books derives from the presence in each of a different aspect of God. This becomes dramatically clear in comparing their endings. Each concludes with a rhetorical question, the only books in the Hebrew Bible to do so. Jonah ends with God’s statement of merciful concern: “And should I not be concerned for Nineveh, that great city, in which are more than 120,000 persons that cannot discern between their right hand and their left hand; and also much cattle?” Nahum’s scornful, dismissive question—“There is no healing for thy breach, thy wound is grievous; all that hear the report of thee clap the hands over thee. For upon whom has not thy wickedness passed continually?”—bespeaks a severe, unflinching refusal to accept that the Assyrians are somehow to be excused and not held to account for their conduct.

Hence my proposal: namely, that Nahum be not only read afresh and in context but that his book enjoy a place at last in Jewish worship. Indeed, to my mind it would be particularly appropriate to chant Nahum’s 47 riveting verses aloud on Yom Kippur afternoon, right after the chanting of Jonah, at a point when congregations always seem to have extra time available as the long day stretches on. This addition to the traditional order of service would offer a bracing enlargement of the meaning of true repentance: the great theme of the day.

Of course, even as these words hit the page, I can’t help wondering whether my devout Grandpa Nahum would approve of such tinkering with Yom Kippur practice. But then I recall that he died, at a relatively young age, just as World War II began. His early death spared him both the spectacle of the millions of Jews killed by the Assyrians of the last century—before those oppressors, too, experienced their “Nahumite” moment—and that of the would-be Assyrians of our own time who not only slaughter Jewish women and children but grotesquely claim for themselves the mantle of “martyrdom.” I’d like to believe that even so traditional a Jew as he, were he to know of these horrors, would join his grandson in asking a rhetorical question of our own: how can we not include Nahum’s message in our observances, who comforted his people by praising the God who to all such base iniquity says No! in thunder?

More about: Hebrew Bible, Nahum, Prophets, Religion & Holidays