One reason I love writing for Mosaic is the quality of responses, and both Adam Kirsch’s and Marat Grinberg’s are especially interesting. They invite real dialogue.

Kirsch, in fact, mentions the Russian philosopher Mikhail Bakhtin, whose key idea was “dialogue.” As Bakhtin used the term, it meant not just one person speaking after another, but an open-ended process in which each participant winds up with ideas neither had at the beginning. Dialogue in this sense is the opposite of ideological (or what Bakhtin called “monologic”) thinking, Soviet or any other, which aims at unwavering adherence to an already known truth. Ideology claims certainty; dialogue fosters wonder. Kirsch closes his response by mentioning how Dostoevsky’s dialogic novels exceed and overcome the much less profound statements in his journalism. I wholeheartedly agree.

Alas, intellectuals too often prefer ideological certainty. Encountering great realist novels that show readers the world’s complexity, they apply a simplistic interpretive system, which for the past four decades they have learned in graduate literature programs. These systems are typically intricate and hard to learn, and so applying them is mistakenly called “rigor.” Students learn “critical thinking,” which never seems to include skeptical examination of one’s own ideas. In “critical thinking,” it is only others who are criticized.

As Russian classic novels show, education does not correlate with decency and ideas do not always enlighten. Those who live by them sometimes constitute what Russians once called a “ministry of darkness.”

Kirsch’s key point is that anti-Semitism, unlike prejudices including racism and homophobia, “feels like an idea.” That seems right about Dostoevsky and thinkers still inspired by his most troubling writings. It is unfortunately the case that some of Russia’s most brilliant thinkers keep devising new and imaginative reasons to despise Jews. A history of Russian anti-Semitism would not be a story of know-nothings.

Sometimes racism can also feel like an idea. It, too, has attracted the highly educated. The “Darwinian” theories that ranked the races once inspired progressives to endorse racially based eugenics. In much the same spirit, Marxism-Leninism “scientifically” ranked social classes, which it defined in a way that allowed class identity to be passed down through generations. It was wise to conceal one’s bourgeois or aristocratic grandparents, and zealous Bolsheviks were always “unmasking” those who did. And having the wrong class background was no trivial matter, inasmuch as the regime exterminated disfavored classes (like the “kulaks”) by the millions. Vasily Grossman famously concluded that Marxism and National Socialism were morally indistinguishable since Marxism is racism by class. We should certainly heed Kirsch’s admonition that hatred as an idea is spreading rapidly in Europe and America today.

Kirsch is also on the mark in explaining that intellectuals often define themselves by what they hate. As he shrewdly observes, “many people who congratulate themselves on their benevolence, and would be deeply ashamed of being exposed as racist or homophobic, take a certain pride in hating Jews.” Hatred of this sort is impervious to dialogue; a favorite phrase is “this is not a conversation!” Those who have lived through, or seriously studied, Soviet history recognize the danger of this attitude, which is what Bakhtin’s ideas resolutely opposed.

Marat Grinberg conveys with special power the way in which Soviet Jews embraced the Russian literary tradition. They were torn between reverence for the Russian classics and irritation at the anti-Semitism sometimes found there. Of course, anti-Semitism is not unique to Russian literature, but to understand the dilemma of Soviet Jews one needs to grasp that the Russian classics were essential to educated Jews’ identity, to the point where “the distinct musty smell of their binding has the effect for many, myself included, of a Proustian madeleine, causing to recall the sheer aesthetic pleasure of listening to Pushkin’s fairy tales as a child, . . . or discovering that Turgenev’s and Tolstoy’s pages were surprisingly not boring at all.”

Russians, including Russian Jews, have valued literature more than any other people, (something I discuss in my recent book Wonder Confronts Certainty). Reviewing the latest serialized installment of Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina, Dostoevsky enthused that at last the existence of the Russian people had been justified. It is hard to imagine a Frenchman, Englishman, or American supposing their people’s existence required justification, but if they did, they would surely not point to a novel! The connotations of the phrase “Russian literature” to Russians were quite different from “English literature” to Englishmen or “American literature” to Americans. The literary tradition was sacred; it was why God had made Russians. The Russian literary tradition is perhaps best compared to the Hebrew Bible when the canon was open and books could still be added to it.

One did not have to be ethnically Russian to appreciate Russian literature this way, as is evident in Isaac Babel’s passionate desire to become a Russian writer. In her speech accepting the Nobel Prize for literature, Svetlana Alexievich mentioned that she is half Ukrainian and half Belarusian—that is, not at all ethnically Russian—but that she could not imagine herself outside of Russian literary culture. When the writer Vladimir Korolenko, who was half Ukrainian, was asked with which people he identified, he replied, “My homeland became, first and foremost, Russian literature.” A homeland in sacred books: that is something Jews can understand.

Perhaps because of the high value Jews ascribe to the written word, no one has appreciated Russian literature more than they. Grinberg describes Friedrich Gorenstein as a writer who blended “fiction with religion, philosophy, and politics in a way that is quintessentially Russian,” while adding a Jewish voice and perspective. Russian Jewish literature belongs to both traditions.

And so one can imagine how Russian Jews felt when they encountered the “stumbling blocks” Grinberg mentions—the frequent anti-Semitism on display. Today, some Ukrainians have a similar reaction to the disparaging comments about “Little Russians” (Ukrainians) also common in Russian literature.

Grinberg mentions that Soviet Jews knew quite well that anti-Zionism meant anti-Semitism. Half a century ago a hypothesis occurred to me when reading Izvestiia after the 1967 war. I recall vividly one article describing a secret meeting (in a cemetery!) of the German chancellor Konrad Adenauer (whom the Soviet press identified as a Nazi) with some prominent Jewish philanthropists and leaders (I forget who) plotting to consolidate their hidden power over the world. It was evident to me that the imagery, language, and ideas came, directly or indirectly, from The Protocols of the Elders of Zion or earlier anti-Semitic works leading up to it. As I read more Soviet journalism, it became clear that the word “Zionism” did not refer to belief in the existence of a Jewish state, as it does for us, but alludes rather to the nefarious Elders of Zion. A Zionist is an Elders-of-Zion-ist. The term suggests a worldwide, almost mystical, conspiracy of evil. In Arab countries, the Protocols are still depicted as authentic. Today among some young Americans, absorbing propaganda developed in the Middle East, the word Zionist seems to be taking on similar connotations. It is not just a cover for anti-Semitism; it also suggests secret, timeless evil on a global scale.

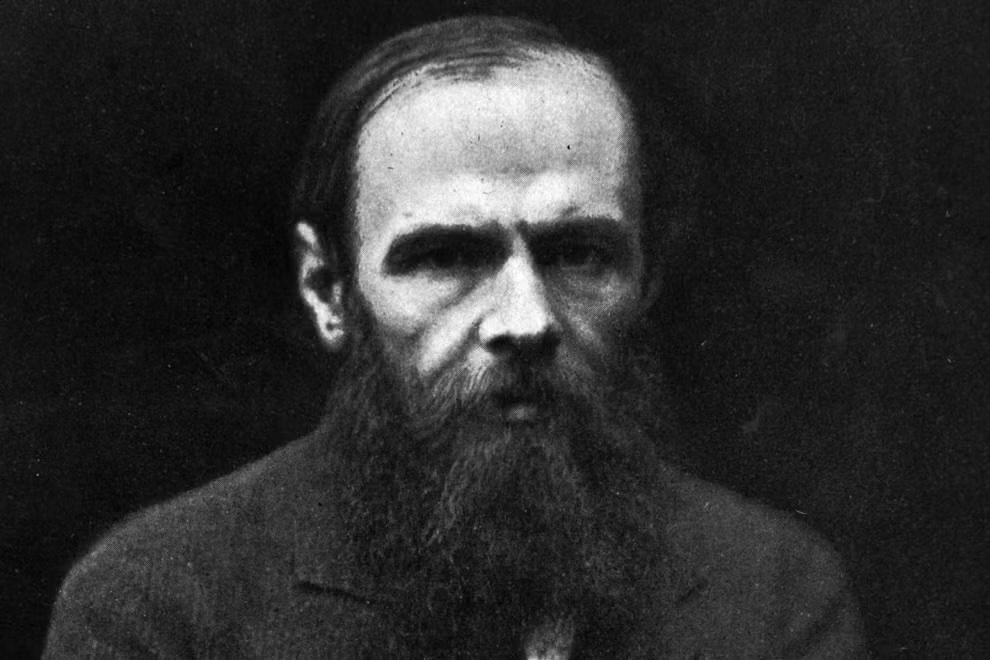

For Jews, Dostoevsky has proved especially problematic because he writes so powerfully about topics central to Jewish consciousness, especially unjust suffering inflicted on the helpless. Ivan Karamazov’s diatribe against God (in the chapter of The Brothers Karamazov titled “Rebellion”) constitutes a modern version of the book of Job, and is, if anything, even more powerful than the original. And so Russian Jewish scholars have gravitated to Dostoevsky despite his anti-Semitism, which they have tried to hide from view. I remember my dissertation advisor, the late Robert Louis Jackson, showing me an early Soviet edition of Dostoevsky in which the Jewish editor omitted some anti-Semitic passages from Dostoevsky’s letters.

In America, too, Jewish academics have actively studied, and sometimes guarded, Dostoevsky. When as a young scholar I wrote an article on Dostoevsky’s anti-Semitism, I received an irate reply not from a Russian nationalist but from a Jewish Dostoevsky scholar. I had broken a taboo. The anti-Semitic Dostoevsky needed to be seen as ours, as almost Jewish in his concerns. And many Dostoevsky scholars have been Jews. Maxim Gorky reports Tolstoy saying that Dostoevsky, who was “all struggle,” displayed “something Jewish” in his way of thinking.

If only values we cherish always clustered together! If only hateful ideas were never found in the company of good ones! Unfortunately, the way cultures and epochs link ideas is contingent. In England, utilitarianism and materialism were at home with liberalism, whereas in Russia they were adopted by revolutionaries, while liberals turned to philosophical idealism. Utilitarianism, they reasoned, could justify killing some people if doing so produced the greater good for others. People today, familiar with only the benign versions of utilitarianism, are often shocked that in America it was progressives who advocated “scientific” eugenics.

So it should not be surprising that people who live by humane values often hold inhumane views. Dostoevsky is far from unique in that respect, and his example is therefore instructive. During the Chinese cultural revolution, I knew a married couple, experts on Chinese history and literature, who followed the Chinese Communist Party line and justified the party’s horrors, and yet no one could have been kinder than they! This couple adopted orphaned children from the ghetto. They endorsed hateful views without any hatred of their own. By the same token, some people who share our views indulge in cruelty. The man who taught me Russian history, the late Firuz Kazemzadeh, used to repeat: “Always remember that there are as many swine on your side of a political issue as on the other side.”

We live in age when totalitarian ways of thinking are on the rise and anti-Semitism has again begun to flourish. If we are to combat these trends, we must understand them. That is why I am grateful to Kirsch and Grinberg for a dialogue that has advanced my own understanding considerably.

More about: Anti-Semitism, Arts & Culture, Fyodor Dostoevsky, History & Ideas, Literature