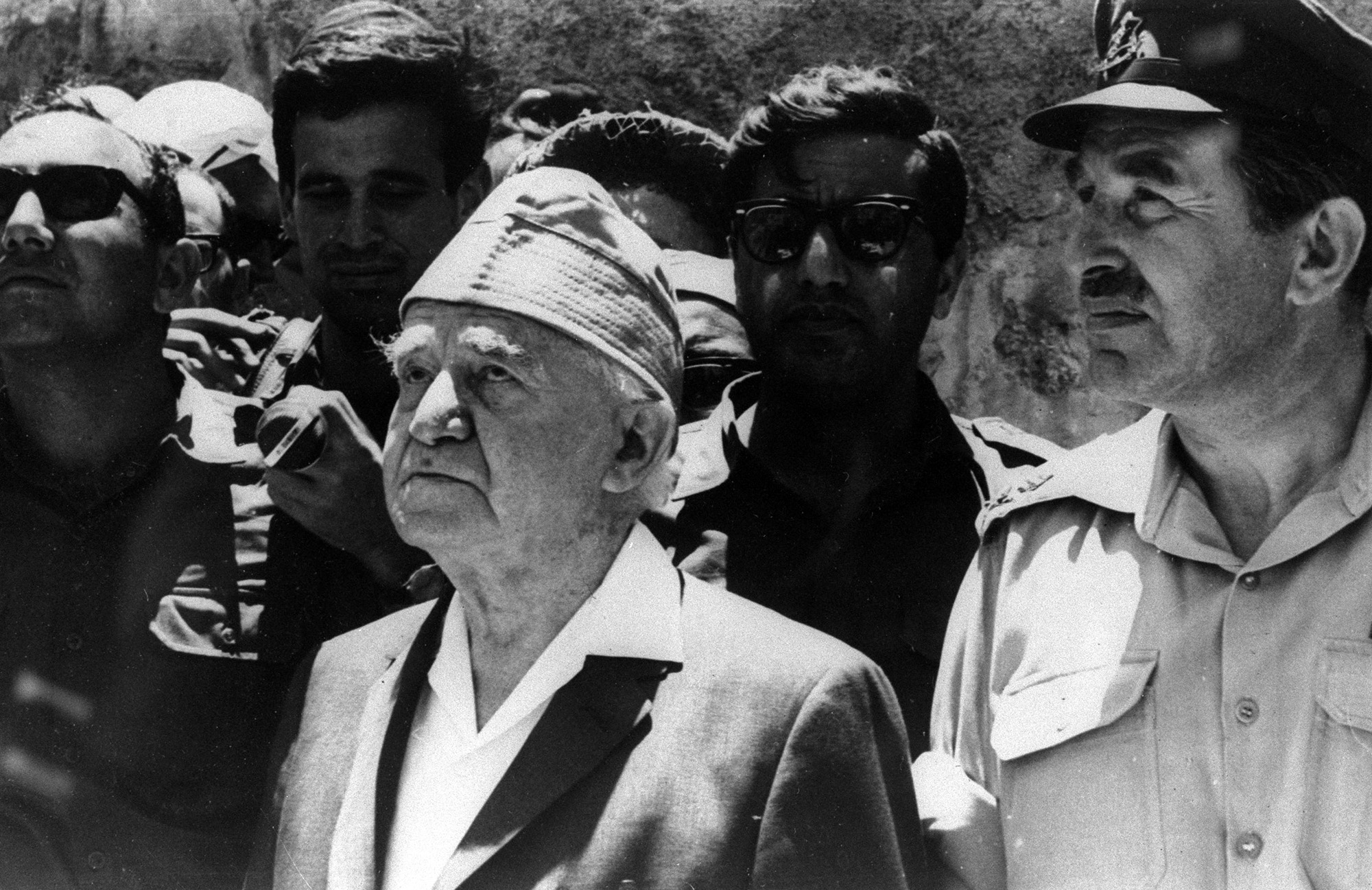

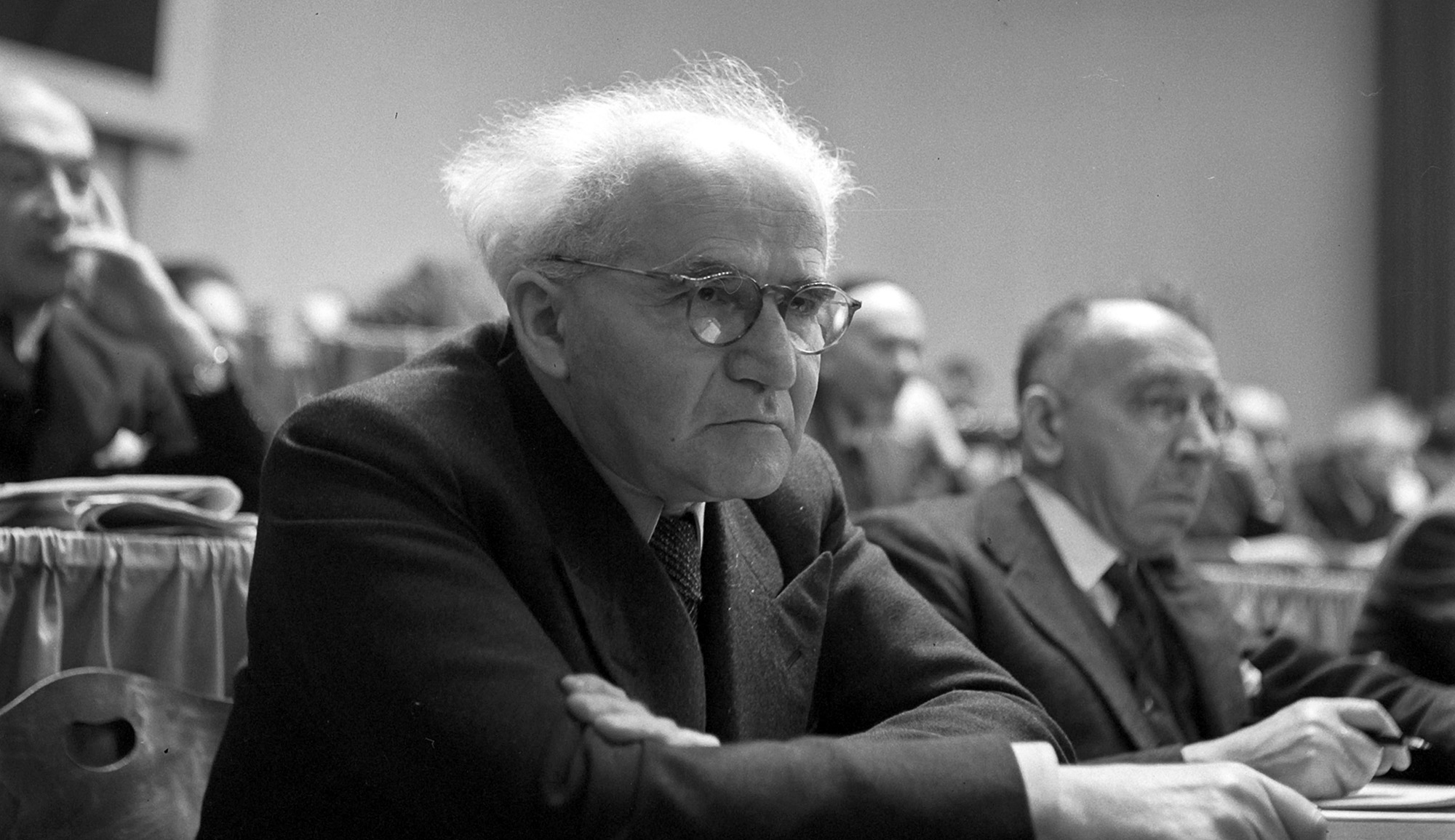

“David Ben-Gurion was Israel’s Washington, Jefferson, and Hamilton in one,” Neil Rogachevsky writes in Mosaic’s feature essay this month.

Ben-Gurion was guided by a simple idea, what he called mamlakhtiyut, or statesmanship. In Israel, such an attitude is more important now than it has been in generations. To understand better how Ben-Gurion applied this concept to the challenges of his time and to think about what it can teach Israelis today, Mosaic invited Rogachevsky to speak with the Israeli historian Avi Shilon and the Israeli political analyst Ran Baratz, all moderated by Mosaic’s editor Jonathan Silver. They spoke on Tuesday, January 30. The video of the event and a lightly edited transcript are below.

Watch

Read

Jonathan Silver:

Welcome, ladies and gentlemen, to this conversation about the scholar and Yeshiva University professor Neil Rogachevsky’s essay asking, “What would Ben-Gurion do?” My name is Jonathan Silver, I’m the editor of Mosaic. And it’s a pleasure to welcome Professor Rogachevsky, along with one of Israel’s deepest and most interesting political analysts, Ran Baratz, and the historian and biographer of, well, among others, Menachem Begin and David Ben-Gurion, Avi Shilon.

I want to begin with a note about us. Americans are used to revering our founders. Even though many prestigious academic historians don’t often write or publish studies about the extraordinary character and accomplishments of the likes of George Washington, or John Adams, or James Madison, nevertheless, the American reading public has what seems like a limitless hunger for them. Fat, new doorstop books about heroic American figures from Frederick Douglass to Ulysses S. Grant are published year after year and are purchased in record numbers. I think many of those books that are purchased are even read. For many Americans, we are used to asking, “What would the founders do?” In fact, that’s the title of a book by one of the most gifted American biographers, Richard Brookhiser. But Israelis have a special reason at this moment to ask Neil’s question, “What would Ben-Gurion do?”

We’re convening this conversation at a moment of a severalfold Israeli crisis. First, there’s the security crisis brought on by the terrorist attacks of October 7th, and the war against Hamas that it inaugurated. The security crisis includes, beyond Gaza, a simmering northern border and menacing threats from the West Bank and beyond in Syria, Iraq, Yemen, and all the spheres of Iranian influence. Then there’s the domestic crisis, which the war has temporarily quieted. In the aftermath of the attack, the home front was required to mobilize, to deter Hizballah, and to operate effectively in Gaza. It seems like the filaments of Israeli society were pulled taut, and the tensions among political factions, and ethnic, class, and religious divisions were for the moment set aside. But we should remember that in the year leading up to October 7th, Israelis were confronting a complex set of legal and political disagreements that led some serious people to wonder if civil conflict was inevitable, and if Israeli society would fatally undermine the Israeli political order.

Now, together, these twin crises pose profound questions about the spirit of Zionism and the aspirations of Jewish sovereignty in the modern age. When the ground of Zion is trembling, and when the basic assumptions and conventional thinking about public affairs are shaken, it’s natural that thoughtful citizens should look to clarify the basic purposes of their government. And that they should do so by turning to its political founder, one of its great strategists. Moreover, a man who articulated a vision of Israel that roots the Zionist past in the desert soil of the Hebrew Bible, thus founding in the deepest sense, by making possible a future, by means of willing the past into its service.

Today, we’re going to try to seek to learn about the statesmanship of David Ben-Gurion. We’ll hear from Avi Shilon and Ran Baratz shortly. But first, I’m going to have a brief conversation with Neil about his essay, and then our expert guests will jump in to pose their questions, and then we’ll turn, at the end of our conversation, to your questions.

My last word of introduction before I turn to Neil is a word of gratitude. I want to thank Mosaic subscribers and members of the Mosaic circle who make Neil’s work possible and discussions like this one possible. We rely on your investments in our work to try to commission essays like this one and to host these discussions. If you have friends or family whom you think would enjoy our work at Mosaic, then please encourage them to subscribe, or buy them a gift subscription. We can help you with that. If you have trouble, just write to us. But now, Neil, let’s turn to you and to the essay. What’s the main argument of the essay? Why did you write it?

Neil Rogachevsky:

First, I just want to voice my own appreciation for everyone for joining us, and also just to start with a word of praise for Mosaic. I’ve always been a fan of Mosaic, but its work has been truly indispensable during this war, and it’s a must-read every morning. It’s a true honor and privilege to be with two of my favorite writers in the Israeli scene: Avi Shilon, one of my favorite historians, and Ran Baratz, an indispensable commentator on Israeli politics and on political-philosophic matters as well.

I think, as I stated at the start of the essay, I’m not an exclusivist in terms of Ben-Gurion. There are other examples of Israeli statesmanship we need. But any reflection on the origins of Israel and lessons we can derive from it has to start with Ben-Gurion. He’s a towering figure over the state of Israel. As I think I put it in the essay, he really combines what Hamilton, Jefferson, and Washington were in the American context. I mean, his imprint was so outstanding.

At the level of the principles of statesmanship, we really have a lot to learn from him at this specific moment. And the essay and my thinking on the matter really hinge on this term mamlakhtiyut, which is a very hard term to translate. Perhaps on this call even, we might have some separate translations we prefer. People have been puzzling over its meaning since Ben-Gurion started using this term in the 1930s; and used it to the end of his life in 1973.

Various terms have been suggested for it: splendor, grandeur, civic virtue, republican spirit, state consciousness. But I really, in consultation with Jonathan Silver, I think the best translation is statesmanship. Ben-Gurion’s idea of statesmanship is one he tried to advance both at the level of practice and at the level of theory. I would say there are three pillars of Ben-Gurion’s idea of statesmanship from which we can learn. Pillar one is putting the national interest above mere partisan interests. Now, this didn’t mean that partisanship was to disappear. Ben-Gurion, at various times, was quite a partisan person. But at key moments, decisive moments in Israeli history, he had the ability to put the national interest above mere partisan interest, to say nothing of personal political fortunes.

The proof is in the pudding. That’s pillar one, you could say, of his idea of mamlakhtiyut. Pillar two is, I’d say, connecting tactical and military means to political ends. That it’s not really enough just to act well in the context of some political fight or in the context of war. You always have to have at front of mind, and even at the front of speech, depending on how much secrecy is involved in a certain mission, a political goal you’re striving for in the midst of your military campaign.

I start this essay noting that he was already out of government in 1967. But after Israel’s stunning victory in 1967, when some other leaders were flabbergasted and basically just did nothing for a while, he tried to take the initiative, and tried to turn what was an astounding military victory into a political plan. We can discuss that if you like. He talked about annexing Jerusalem, which did ultimately happen; keeping control of the Jordan River Valley; and dealing in a serious political way with the question of Gaza and the West Bank. So that, I would say, is pillar two. Then pillar three, also very relevant for the developments of the last years, is approaching culture war in the spirit of compromise.

This was, I think, a key aspect of his statesmanship, and you can follow this through his political career. Especially from ’47, ’48 onwards through his premiership, Ben-Gurion always expressed the view that we’re never going to resolve fully the thorny religious, constitutional, cultural issues that have divided Israel and will continue to divide Israel. We’ve got to approach them in a spirit of compromise. Yes, at certain points a leader is going to have to act decisively in one direction or another. But we’re going to need to act so, for instance, that the secular and the religious both have some purchase in the future of the state. We can’t proceed as if we’re totally going to crush either one side or another. That was extremely important, and I think there are all kinds of lessons we can draw from that through Israeli history and up to the present moment. Those are, I’d say, the three pillars of mamlakhtiyut.

Jonathan Silver:

Neil, there’s one current in the essay, which is this very fascinating moral and civic analysis of economics and the role that wealth plays in the fabric of a society. Tell us what you took from Ben-Gurion’s statements and writing on this question.

Neil Rogachevsky:

It’s such an interesting one to think of now in the context of this extraordinary economic development of Israel over the past two decades, right? Israel going from a country which still looked, in the early 1990s, like an incredibly poor country to what it is now. I remember visiting in the late 90s for the first time, when having a car was seen as a sign of extreme luxury. This extraordinary transformation where we now see that Israel has become, and hopefully will remain, a country with a GDP akin to that of certain Western European nations.

This was a concern of Ben-Gurion. Of course, his principal concern was, “We need to develop the strength of the state.” He was much more flexible in terms of the means to accomplish that than he’s often given credit for. Typically the evaluation is, “Oh, he’s a pure Labor Zionist, socialist economics.” There’s some truth to that, but if you follow his career, his lodestar was national development. If state means could do that, that’s great. If more private means could do that, that was great. But he was much less ideologically rigid than he’s often portrayed as being, but he had this interesting diagnosis of the problem of wealth. We recall other great statesmen and political thinkers in history, stretching from Plato to Montesquieu, who worried about this question of, “What could wealth and riches in a country do to the spirit of civic engagement, of patriotism, of the cultivation of citizenship?” which was necessary for the flourishing of the state.

He and many other early Zionists worried about this. And they cultivated a sense of austerity, “We’re going to live in simple circumstances.” Ben-Gurion famously moved to the Negev, Sde Boker, out of a sense of, “Give an example for the future generations of the kind of work we would need to put in, the harshness.” Harsh sacrifice, in a way, was required to make this thing go on. It came up practically much less at a time when Israel was struggling to get by economically. There wasn’t much wealth to go round.

But now I think this is something we need to think about in the context of the start-up nation. How do we get buy-in to the state? People who otherwise have economic opportunities they never had in Israel, say pre-2007, now also have many opportunities whether in California, in Europe, in other places, or still in Israel. But with one or one-and-a-half feet in the United States, how do we capture that energy and turn it towards the national development of Israel? That’s something we ought to think about and the state will have to focus on after the war. We’re going to need to ask some serious questions, like how do we have extend the term of army service? How do we bring the best people directly into government service, whether in the army or elsewhere?

Jonathan Silver:

And it will need to regenerate the foundations of wealth creation and prosperity that have been undermined by the war, in some real sense. Both sides of that dilemma have not disappeared from us, but I think that one can derive from Ben-Gurion the moral calculation that there are civic consequences to prosperity, just as there are civic consequences to poverty.

Neil Rogachevsky:

Yes, very much so.

Jonathan Silver:

Let me ask about another thing that I’ve always been fascinated by, which you touch on in the essay. We sometimes think of Ben-Gurion as this eccentric who’s reading Plato and other great thinkers, but also publishing all this stuff, all these essays, and giving speeches on the Bible. There has always been a role for great visionary founders, let’s say statesmen, who act as a political teacher to their people. And there is some very deep way in which Ben-Gurion saw one of his primary roles as teaching Israelis their new history, or shaping for them a sense of history. It seems to me that rooting the contemporary Israeli experience in a certain kind of contoured past is one of his great achievements.

Neil Rogachevsky:

Yeah, very much so. That’s really wonderfully said. Maybe I could start with an autobiographical note. You mentioned eccentricity. Before I started scholarship into Ben-Gurion, my tendency was always to view this as simply a kind of vanity, that of an autodidact. Lower-class person from Poland rises up in Zionist politics, and he’s face-to-face with people with much more bourgeois, fancier backgrounds. These German lawyers in the Zionist movement with doctorates from Heidelberg, and Berlin, and other places. I always thought his turn to the Bible, and Thucydides, and these other texts were simply a kind of vanity. A person with a chip on his shoulder trying too hard to show off his learning. Through studying this, I see that yes, maybe there’s a certain pride or vanity there. I don’t want to dispute that completely, but his learning was serious. What he was trying to do was audacious and extraordinary, and you put your finger on it.

He saw that we had entered a new epoch in Jewish history, or at least we had returned to political sovereignty for the first time in almost 1,900 years, and that this required us to refresh our sources of political insight or reframe. Everything, in a way, needed to be reevaluated. Again, there’s often a crude caricature of Ben-Gurion and other Labor Zionists, “Oh, they were merely Palmach.” That there was the Bible, and then Palmach, and the whole history of Judaism was darkness, otherwise. If you read the things you mentioned, his essays on the Bible, other public speeches on prophecy and other political topics, you see that that is, in fact, a caricature. Yes, he wanted to draw on the Bible, but what you see him doing in all of these extraordinary essays and speeches is trying to reconstruct on the basis of the whole Jewish tradition, lessons for politics that are internally derived from the Jewish tradition, of what is the Jewish idea of justice. What is a Jewish idea of prudence?

In one of the essays, his final essay, actually, or final essay written on the Bible, published in 1968, I think. I think it’s called “The People and Prophethood.” It’s this extraordinary reflection on political prudence within the Bible, i.e. how biblical religion, in spite of a stringent view of ritualism and the importance of ritual practice, nonetheless allowed political leaders to deviate from the law when national emergency requires. He was thinking about this, trying to teach the nation that yes, you could deviate from the strict laws of Shabbat when military purposes required it. What’s so interesting about him is yes, he read Plato, read Thucydides, read Greek authors in order to articulate this, but he saw it as very important to draw this from the wellsprings of Jewish tradition itself. So these things really repay reading and study.

Jonathan Silver:

Neil, let me ask you one final question and then Avi, in just a moment we’ll turn to you. But Neil, Ben-Gurion is not a systematic thinker like some of the political philosophers that we study around seminar tables. He was a man of affairs, a very deep man of affairs, whose learning is serious, as you say. But there’s always a danger to turn to a man of affairs, whose work is often addressed to particular circumstances, and elucidate from his addressing particular circumstances elements of his thought that you apply in other circumstances. That gives the interpreter the freedom to project onto Ben-Gurion his own preferences, his own political judgments. That’s a very hard thing to do. That’s something that a scholar of Churchill, or Lincoln, or Julius Caesar has to contend with, but I want to know how you contend with it in your treatment of Ben-Gurion.

Neil Rogachevsky:

That’s very well said. As I think I say at the beginning of the essay in a caveat, it’s simply dangerous to turn to any human being, philosopher or politician, who’s been dead for 50 years, in search of direct lessons that one could apply in very different situations. I hope I avoid saying, “Oh, Ben-Gurion said this about the territories, ergo we have to follow in this direct way.” No, I think we have no choice but to do our own political thinking. One of the things you learn, actually, from watching great statesmen, is the role of contingency, and how swiftly things change, and your need to adapt to those changes. But I still think this exercise is useful at the level of principles, that the principles which we can see both from his general, political, or theoretical essays, and from his practice can serve as an example—not of what specifically to do, but of the kinds of principles that can guide us as we think through pretty unique challenges.

These three pillars I mentioned are pillars at the levels. How to put the national interest above mere partisan interest. Why culture-war issues for people like the Jews would be very hard to resolve, and that one should proceed with a sense of caution and moderation in that way. Connecting tactical and military means to political ends. These, I think, are general principles which can help us—especially as we try to educate the young and educate ourselves for the responsibilities of statesmanship—to develop and deepen our political thinking. I think I’m on solid ground as a Ben-Gurion scholar as to articulating those principles. But when I turn to specific cases, then I’m just another guy with a Twitter account. And other people, of course, will judge how these principles would apply in our own times in very different ways.

Jonathan Silver:

Right. Though, I suppose, you’re distinguished from just another guy on Twitter because your study of Ben-Gurion has helped you refine the questions that are essential from the questions that are peripheral. Let’s turn, Avi, to you. Avi, you’ve studied Ben-Gurion’s principal political nemesis, and you have studied Ben-Gurion himself. I’m eager for you to join and ask Neil your questions.

Avi Shilon:

Well, first of all, thank you, Jon, for inviting me. I am a huge fan of Mosaic, and your podcast, and always learning from it. And Neil, your article is great. I prepared eight questions, but you can stop me at three, because you know this is a subject that it’s hard to stop me from talking about. First of all, with respect to the notion of mamlakhtiyut, I think that we are on the same page with our understanding that mamlakhtiyut means mainly to put the state’s interest above any sectarian, personal, or political interest. Mamlakhtiyut was established, actually, by Ben-Gurion as an idea after giving up on another idea. But the problem is that the idea of mamlakhtiyut stands against another idea that Ben-Gurion always promoted, the pioneering idea, which is, “Do it yourself. You don’t need to ask the state. You don’t need to ask the party. You should know what to do and you should lead by your own hands or experience.”

Pioneering is also, to my mind, part of the rebellious nature or character of Ben-Gurion. He was always a rebel against Jewish history, Jewish religion, against a different kind of economical system, even against the British, and eventually he rebelled against his own party, Mapai, the party that he had established. So if Ben-Gurion really believed in the idea of mamlakhtiyut and also pioneering, do you think that we can reconcile between them? Or maybe the attempt to merge them is impossible or even the problem. Moreover, you talked a lot about the need for mamlakhtiyut nowadays, but maybe we’re more in need for pioneering, because to be a pioneer is also not to be locked in the same old conception. So how do you see the tension between mamlakhtiyut, statism, and pioneering?

Neil Rogachevsky:

That’s a fantastic question. It’s not something I touched on very much. The pioneering aspect certainly comes out in the question of his moving to Sde Boker. I think it’s very hard to reconcile them. At a certain moment when settlement was amidst struggles, building the Yishuv under the Tower and Stockade was necessary. The importance of the pioneering spirit could pre-emanate over the political logic, the logic of statism. But as a state matures, and I think this applies today, I think the mamlakhtiyut imperative comes to predominate. You see this in his discourse, of course, pioneering remains strong. But I think—and perhaps it’s, again, my preference reading into this in a certain way—I think the political law is what we need to focus on more.

I studied this in writing Israel’s Declaration of Independence. We see when Ben-Gurion takes over that process of writing the declaration that the pioneering aspect, which had been strong in the previous drafts, is still present in the final draft of Israel’s Declaration of Independence, but really the political purpose, the natural right of sovereignty, is brought in and takes over. To me, that’s the thread of his thought that we really need to pursue today.

I mentioned in one of my previous remarks to Jonathan that the idea of statesmanship certainly allows for the development of new concepts as circumstances allow, for thinking anew. Certain things we thought we knew before the war, we’re going to have to think anew again. That comes, I think, from a kind of political prudence, which you develop from having a national sense of, “I’ve got to rethink the whole situation of Israel vis-a-vis its neighbors, vis-a-vis ourselves, and so on.” I’d like to think more of the role of pioneering today, but that, I think, is the thread that I would go to, at least.

Avi Shilon:

Now I have a bit of a difficult and very concrete question. I was wondering, what do you think Ben-Gurion would’ve said today under the context of mamlakhtiyut about the possibility of a hostage deal, if the formula for the hostage deal is, “Stop the war. If you want them, you need to stop the war”? Because here, the question is what is mamlakhti? Whether mamlakhtiyut is to get all of the hostages, even if, at least allegedly, the interest of the state is to continue with the war, or vice-versa. Because this case can teach us about what is the real meaning of mamlakhtiyut in a concrete case.

Neil Rogachevsky:

Yeah, the questions are unfathomably difficult. A short answer is, I don’t know. When I first thought of it, I was tempted to reimagine the old Ben-Gurion dictum of, “We’ll fight the white paper as if there’s no war, and we’ll fight the war as if there’s no white paper.”

That we’ll try to get to return the hostages as if there’s no war, and we’ll fight the war as if there are no hostages. So my sense would be he’d be following the current governmental approach on this. Not relenting on these two purposes, out of the sense that we’re determined to change the political reality now in Gaza. And if we’re not able to do so, then this specific hostage crisis is just a potential beginning. We’re trying to make a decisive change in this direction. So seeing these problems as interconnected, and articulating why they’re interconnected would, I think, be an important political goal. But that’s just how I see it. I’d be curious for your own thought on that.

Avi Shilon:

Well, personally, I think that in order to sustain, to maintain, or even to implement the idea of mamlakhtiyut, I would stop the war and get the hostages. Because mamlakhtiyut is first and foremost about Israeli society. And in this case, the Israeli society or the Israeli people are the real interest of the state, though it might sound a bit of a contradiction. It’s a tough question, because Ben-Gurion was a leader that could call the citizens to sacrifice themself if needed. I think, in this case, it’s a bit different because of issues of responsibility—whether the government is responsible for what happened on October 7th. I mean, responsible in terms of protecting the people, of course. This is why I think that Ben-Gurion eventually would’ve voted in favor of a hostage deal even if it is not the full interest of the state.

But I would like to ask you another question. As you wrote, Ben-Gurion put a lot of emphasis on the issue of unity. It is quite clear from your excellent paper that he didn’t want an unnecessary cultural war. This is why, for example, he was ready to merge state and church, though he was against it in principle. Or this is why he was ready to cancel the socialistic stream of education, even though he was in favor of it. He didn’t want an unnecessary cultural war. It was clear that you are hinting—or not hinting, you are precisely talking about an unnecessary fight or rift in Israeli society over judicial reform. I agree, but it is an interesting case. Because unlike Menachem Begin, Ben-Gurion didn’t favor constitution and didn’t want the justices to interpret the laws just to implement them. He believed in the power of regular laws and the power of the Knesset. He didn’t want the supreme court to interpret laws; he was much closer to those who are in favor of the judicial reform than to those who were against. So where was Ben-Gurion here?

Neil Rogachevsky:

There are two sides to this. He was both opposed to a formal written constitution, which he successfully quashed, and he acceded to the Harari compromise in 1950, which produced a system of basic laws. And he opposed the development of judicial review in Israel in a speech, which I really think is a landmark speech, which Mosaic was kind enough to publish. We see both sides of his political, constitutional principles there. No formal written constitution and no judicial review. He didn’t win every battle. These things developed in a very complicated way. Clearly there were some very good arguments, good Ben-Gurionist arguments for a certain kind of judicial review. I’ve been for a long time sympathetic to some of the criticisms that were offered of Bagatz, of Israel’s supreme court, and of the fact that it has more power than any founding settlement, if we could design it, would permit. There are all kinds of inadequacies there.

My Ben-Gurionist reservation to this was the question of political logic. Not so much the content of reform, not reform in general, but how that is brought forth in a society. Whatever the merits of the proposal, what does this do to your society, bringing it through this, I think, very partisan way in which the judicial reform program was pursued, and in this question of culture war weakening the commitment, rightly or wrongly, of a certain segment of your society to the future of the country. It leaves one side feeling that, “This is just being shoved down our throat.”

In terms of the specifics: yes, he was clearly opposed to rule by unelected judges. Ben-Gurion and I myself are not opposed to certain kind of judicial reform. But the way this tore up Israeli society over the last year and distracted us, we now see, I think, from focusing on these essential questions: self-defense, normalization with Saudi Arabia—major developments happening in the Middle East—to me, that would be the decisive mistake from the standpoint of mamlakhtiyut. We’re distracted by something that may be important, that there are some issues in Israeli society that one could mention, but which do not compare to the major challenges facing us. How do we break open this normalization with Saudi Arabia and perhaps truly forge a new path to peace? That’s what we should be focusing on.

Jonathan Silver:

Avi, I want to come back to you in a minute, but I’m eager to get Ran involved.

Ran Baratz:

First, the pleasantries. Thank you very much for Mosaic, the wonderful Neil, the wonderful essay. This combination, I think, works extremely well in elevating these issues to the center of the public debate. And getting it to where it should be on substance and central issues rather than, just as Neil writes, political distractions that take our whole attention and remove it from the most important things, and then we get where we are now. So thank you. Neil, I would say I have a few rebuttal points, but I want to get to the most important ones. Maybe the spirit of Ben-Gurion in your essay that disturbed me most is presenting him as if he is a sort of a liberal, comparing him to Hamilton. I think he’s more Jefferson. I mean, he’s not a limited-government kind of guy, and this is why we don’t have a constitution.

If you ask me, I’m more cynical about that. This is not a question of a cultural war. A cultural war is an excuse. Actually, he didn’t want a constitution, because what the constitution does is limit governmental power. Now, I can defend it by saying at that time, Ben-Gurion thought that limiting governmental power would be an existential threat, because this was a time of war. This was a time of poverty. This was a time when you had to absorb a million new olim. So you had to have the most powerful government you can think of. As most leaders do, he thought that he was the right guy at the right moment, so you don’t need to limit him. But, I think it’s a grave mistake.

I give him a lot of credit, and I agree with you 100 percent about the type of leadership and political calculation—international, military, domestic—that Ben-Gurion embodied. I think he did a profoundly excellent job in many aspects. But on the constitutional aspects, on the institutional aspects, I think presenting him as if he had some sort of liberal, pluralistic attitude to him is. . . . Listen, this is the guy who spearheaded a violent battle against Revisionist Zionists in Israel. Just think of the fact, while his people were shooting at the Altalena and the Irgun guys in the water, it was Begin who said, “We will not fight back.” Which shows you that had Ben-Gurion wanted, he could’ve reached some compromise with Begin. Begin was not out for war. Even when his own people were shot, he still said, “I will not shoot back.” So I would say, retrospectively—maybe I’m wrong—but it seems as if Ben-Gurion could’ve handled it a little bit more moderately.

In that, and before that, of course, if you go to the 30s, Israel reached a point of a civil war in ’33, ’34 after [the socialist Zionist Haim] Arlosoroff’s murder [by a Revisionist Zionist]. There was really a lot of violence involved, spearheaded by Ben-Gurion’s people, and he wasn’t apologetic about it. He was very threatening in his speeches toward Revisionist Zionists, and accusing Jabotinsky and his people all the time, comparing them to Nazis, et cetera.

My last point is about the education. We have three or four kinds of education streams in Israel, right? The Haredi, Mamlakhti, et cetera. To me, [allowing] this seems a shrewd political decision rather than a proof of a liberal or pluralistic state of mind. Because Ben-Gurion wanted the religious in his government because he wanted to exclude others, so he paid this political price. There was one religious party which included all the religious factions. Back then, it was the only time that Haredi, National Religious, and Mapai sat together.

So he gave them a little bit of what they wanted, thinking that, “This is not going to last. I mean, the Haredi are going to assimilate. We’re building a modern state, so we’ll give them something now and they will disappear.” Again, this is one of the things you mention as real proof of a liberal spirit.

Now, I do agree that he was a democrat, and I do agree with your comparison to Churchill and the hard truth that a leader must tell his people. I wish we had that spirit today. We don’t. Today we have politicians, they have propaganda rather than hard truth. I do admire him for that, and I think he did it. He did it in ’56. He did it in the formation of Israel. He did it before the formation in Israel. He said, for example, in ’46, ’47, “We are unprepared for war,” and he took hard measures to make Israel more ready for a conventional war. So: a lot to admire there, and a democratic spirit telling the truth to the people, but not liberal in a limited government kind of way, and not pluralistic in really giving credence to his opponents’ views and ideology. In that sense, I think Revisionist Zionists have much more to offer. Also in that sense, Israel today is much more Jabotinskian, I would say, than Ben-Gurion. Over to you.

Neil Rogachevsky:

Well, thank you very much for that incredibly lucid presentation. Look, I agree with you in part. When I say he didn’t want a constitution because he was worried about a culture war and pluralism, that also sits with political calculation. Every political figure is interested in his own survival and flourishing. Yes, he was worried. He didn’t want to have restraints on his power. I mention this in this essay and some other things I’ve done on Ben-Gurion in Mosaic, there is something of a tension in his soul between what I would characterize as the liberal constitutional side, whether that’s written or not, and the mid-20th-century progressivist side, which is worried about any limits whatsoever on governmental power. That clearly is there, right?

For instance, he really admired FDR, but he hated the U.S. Supreme Court for trying to limit any aspect of FDR’s New Deal. Because he thought, “Okay, parliamentary power, no limits whatever on the power of parliament.” He’s a complicated figure. There are many interesting tensions to look into. Maybe this is my own political principles or ideology, but I still think the liberal side of Ben-Gurion gets less credit than it should.

I was raised to look at, like many people, the contrast between Ben-Gurion and Jabotinsky or Begin, to see that as a main axis of ideological conflict in early Israel and subsequently. And there is a lot there. It’s very enriching to compare the Revisionist aspect and the Ben-Gurionist aspect. But I’ve come to see through studying Ben-Gurion’s debates with the left flank of Mapai and Mapam in ’47, ’48 and ’49, he’s not given enough credit to the extent he totally undermines the far-left priorities, you could say, of people in the Labor Zionist milieu. I just mention a simple example, now it seems absurd, but it was a living issue at the time. There were voices in Mapam, and even a few in Mapai in ’47, ’48 who were calling for open alliance with the Soviet system. Why not? Britain, America had gone back on the partition plan. The British Empire had been stifling us here, keeping our people in DP camps in Cyprus. Let’s openly align with the Soviets, right? He fought against that.

On the question of pluralistic education, yes, there is this motive of, “Okay, we want to have an alliance between Mapai and the small religious parties.” But there were voices, and here not only in Mapam, but voices in Mapai who looked at the question of Yemenite immigration, and first instance said, “Okay, we’re going to keep these people out. We’re not going to have official Law of Return to deal with this. Or if they come, we’re going to subject them to one single education system. We’re going to make them into Ashkenazim, turn them all into good Labor Zionist.” He fought against those tendencies.

It was through Ben-Gurion, and Tom Segev shows this very well in his book, 1949, which this system of pluralistic education was brought through in Israel. There was some soft tyranny against Revisionist and newcomers in Israel, of course. I’m not going to minimize that. But because of those decisive choices, he basically opened the door for this new pluralistic Israel, which became much friendlier to traditional Jewish ways, traditional Jewish practices, and Revisionist politics later on.

So that’s my move. There’s a ton to learn from Begin, as both of your works have shown so beautifully. But when we compare Ben-Gurion against people who would’ve been in charge were it not for Ben-Gurion, right, because Begin was out of the game at that point, he comes off much better, precisely from this ;iberal point of view.

Ran Baratz:

So just I agree with that, but that’s only because Jabotinsky died in 1940. So he was eight years short of the foundation. I don’t mamlakhtiyut is really a compound philosophical notion, I think it’s a general notion, an intuition that Ben-Gurion has. But the problem is, because he was such a statist in his thinking, which is why Israeli institutions are so unlimited and we face those constitutional crises continuously for 40 years or so. Mamlakhtiyut today in Israel, when people say that, what they usually mean is, “Don’t criticize governmental bodies and institutions, right? If you criticize the idea of justices and supreme court, or if you criticize any judicial advisor, et cetera, then you are not mamlakhti.”

This kind of statism runs so deep, I would say that mamlakhtiyut today is not statism, it’s deep statism. So in that sense, this is a terrible heritage, and it’s a little bit, I don’t know, disappointing. Because there were, not only in the radical left, but some of the radical pioneers of the left were almost anarchists. They were not statists at all. “What we do on the ground matters.” Right? You had that voice, and Ben-Gurion didn’t like that at all. They lived as communists, but their political, the state perception was, “We don’t need the state. Just let us roam.” And in that sense, they’re almost a counterpart to some aspects of Jabotinsky on the radical left. These are exactly the people that Ben-Gurion ostracized. It’s very interesting, the moderate right, which was liberal, and the radical left, who are anarchists, were the ones he set aside in order to have maximal governmental power.

So it’s interesting to read back and look at that. Even Jabotinsky says, “In my Utopia, is an anarchy.” You can’t materialize it, well, you always need government, et cetera, but the most freedom is the best option. This is like the compass. And on the radical left in Israel you had similar voices that, “In our community we are very restricted, but our political agenda is that we don’t need the state. We are free to do what we do.” In that sense, the moderate right and some of the extreme left in Israel, in a unique way, this didn’t really happen in other places as far as I know, they were both agreeing on some constitutional value of freedom and liberty, and Ben-Gurion rejected them both.

Now again, this is not to take from Ben-Gurion anything, great leader. I admire him. I think it was necessary. Without him, I’m skeptical that Israel could’ve been formed and survived its first few years. I also 100% agree on the aliyah issue of Mizrahi Jews. This is like credit, an eternal credit. Whatever wrong he did, he bought himself a place in heaven if only for that. And he has many other things that bought him a place in heaven, I’m sure.

But in that sense, it’s ingrained statism that is completely intolerant to the idea that citizenship is liberty rather than mamlakhtiyut. Or in a way, being a citizen has in it the request to limit government, which is not a necessary idea, but it is part of a Western tradition to think that way, that you empower the citizen by limiting the government. This was something that Ben-Gurion was, I think, tragically misinformed, and left us with a political heritage that we are still furious over, in a way, between the liberal right in Israel, and I know the state is left, which in its own way really follow in the footsteps of its founding father.

Jonathan Silver:

So Neil, I’d like you to respond to that, and then we’ve got a few questions that I want to pose from the group.

Neil Rogachevsky:

Yeah, maybe with the interest of getting, I see 15 Q and As, all I would say to that I agree in part, disagree in many others. I think my task would be, or our task, to substitute a true or more moderate understanding, which I think is a real understanding of mamlakhtiyut, rather than pure deep statism, as you would say. Yes, I think we need criticism of governmental institutions, we need reform, we need to be able to have a debate about those things.

Jonathan Silver:

Avi.

Avi Shilon:

I would like to add something. In a way, I agree with Ran that Ben-Gurion was not a liberal. He was not a liberal, because he put the community before the individual. He put the nation before the individual. He was much more of a republican. This is true. And by the way, he believes that your duties, the community, are your rights. Once you fulfill your duties, you’re actually fulfilling your right. But I totally disagree with the idea that criticizing the state institutions are like the new of today. Not criticizing, I mean the problem is that those who criticize really criticize, they try to break the state’s institutions. They try to look at it as a deep state, as Ran said, and this is the problem.

I also think that looking at the Altalena Affair as a Ben-Gurion mistake is correct, in a way, but of course, it is much more complicated. First of all, Ben-Gurion was hardly against the Palmach, the left wing. He acted against the Palmach just like he acted against the Altalena. Secondly, the Altalena Affair started as an agreement between Begin and the state. And the fact that this agreement was breached was not only because of Ben-Gurion. It was very important to show to the left and to the right alike that we have one law and we must obey it if you want to establish an army in time when you need to merge different groups into one army.

Lastly, I just want to say that to my mind, a major part of mamlakhtiyut, and this is something that the current leadership of Israel is totally missing, is the idea of responsibility. You know that when Ben-Gurion retired, he decided to quit on 1963, one of his explanations was that it’s not good for a democracy. It’s not good for a healthy society to have a prime minister that will rule for over 15 years, even though he could’ve continued. So the idea of sacrificing yourself, in a way, taking responsibility for the people, not just asking the people to take responsibility, was a major and still a major part of the idea of mamlakhtiyut today.

Jonathan Silver:

Okay. Listening to the three of you, I am now thinking about Ben-Gurion as a republican, as a liberal, and as a Leninist. So now it forces me back to learn in Neil’s essay. There’s something which comes up in the questions, and which I myself have been wondering about, which I want to put to all three of you. It is a dimension of Ben-Gurion’s statesmanship that we’ve not focused on but is clearly one of his enduring legacies. That is this whole business of the periphery strategy, the way that he sought to conduct Israel’s foreign policy, and in particular, why he saw a relationship with the United States as being of strategic value to Israel in the 20th century. So let me just put that to the three of you as a way to round out our picture of Ben-Gurion’s enduring political practice that we can try to learn from.

Neil Rogachevsky:

Yeah, I’ll just be quick. I mean, there’s so much, and more books actually ought to be written on this now. There have been some good ones on Ben-Gurion’s foreign policy. Critics of Ben-Gurion, including perhaps the current prime minister might say that, “Oh, Ben-Gurion was late to the game in seeing the direction of world foreign policy.” He famously thought the Ottoman Empire was going to endure past World War I, thought enough of its endurance to learn Turkish. He was late in viewing what Jabotinsky saw early as the Iron Wall challenge of the Arab question, that mere economic progress was not enough. So I grant some of those criticisms, but by the time we get to ’47, ’48, and it was clearly the case through, I think 1960, he had this breadth of vision which allowed him to see where the wind was blowing.

He saw that, in the face of the example I already mentioned, people who were advocating for open alignment with Moscow. He saw this was a nonsense, terrible, dead-end strategy. He certainly didn’t advocate for open alignment with the United States. Freedom of action was to prove extremely important. Let’s remember that America, in spite of popular support for Israel, and Truman’s support ultimately for the establishment of state, had official arms embargo onto Israel down into the 1960s. So there’s no way of having official alignment.

Although one untold story, Israel’s alleged nuclear program, does it come from France or there’s some American involvement there? Interesting historical work to be done. So even in the midst of that embargo, there was American support, but he clearly saw and he did extraordinary work, I think, gradually, subtly turning Israel to the West without openly aligning in the Cold War. By that time and through his premiership, he was clairvoyant as to where Israel’s strategic interests actually were located.

Ran Baratz:

This is a part of Neil’s essay, which I just highlighted in agreement. I think Ben-Gurion maximalized flexibility in foreign affairs. Of course, part of it in retrospect, it seems obvious at the time, if you look at the different powers, the United States had an embargo, and it was a tough relationship, and the Soviet Union was turning towards the Arab nation, et cetera. So flexibility, but in retrospect, it’s all easy. He was a genius to understand that in real-time, and understanding that you have to cautiously make an advancement toward the West, which will be the winning side. And I would say what characterizes Ben-Gurion’s foreign policy and military policy, which are usually intertwined, in my mind, is an astute sense of realism.

He was a real realist. He understood power. He understood the power internationally and militarily. This is something that I think the West in general lost. This kind of understanding of the shifting powers, and how they affect your foreign policy and your national security, has been lost. And Ben-Gurion, with Jabotinsky, I think there they are two very strong realists. You can argue Jabotinsky was wrong here, Ben-Gurion was wrong there, it doesn’t matter. They saw the world through that prism. Some of his maneuvers internationally, I think, were genius, and I think led to strengthening Israel in a way that no one could’ve anticipated. In fact, people waged war against Israel, and Ben-Gurion managed to put us through all those crazy situations victorious. And for that, again, eternal credit. This is a realism that we should really restudy and reimplement in our current leaders.

Avi Shilon:

In this case, I totally agree with Ran. Even more overall, I would term it total flexibility in terms of relationships, in terms of the Israeli borders, by the way, and even in terms of your alliances. For me, this is a major difference between him and Begin. Begin saw international relation in light of moral justification or in light of Jewish history, while for Ben-Gurion it was really clear and sheer real politics. By the way, this is one of his last letters to the next generation of leaders of Israel, “Think always in terms of real politics.” And I think the best example of it—and Neil, you address this issue of real politics—but the best example of it is the reparation agreement with West Germany a few years after the Holocaust.

Because for Ben-Gurion it was very important to adjust yourself to the thinking that you need to do whatever you should do in order to strengthen Israel. Don’t put moral justification, or religious justification, or just principles that can hold you or stop you from reaching better alliances. By the way, he was among the few that already during the Second World War, he said that the next superpowers of the world would be India and China. He even urged Nixon—it was one of his last letters—to have a relationship with China, because he believed that they were going to surprise the U.S. and USSR.

Jonathan Silver:

Okay, let me pose one of the many intelligent questions that we’ve gotten from Mosaic readers. It has to do, Neil, with the question of Israel’s political forms. Which is, I know, something that both with Ben-Gurion as a teacher and inspiration, but also yourself, for years, you have been studying the forms and formalities of Israeli rule. Asking yourself how it helps Israeli democracy, how it undermines Israeli democracy, how it helps to establish order, how it undermines order. Could you say something about the parliamentary system of Israel and Ben-Gurion?

Neil Rogachevsky:

I’m so glad you asked that. I take every opportunity to talk about this when I can. Yeah. Ben-Gurion shared this with others in his party who sought the strength of the state, the governing institutions of Israel turned out to be incredibly weak and remain so in many respects. I don’t have to remind you, an educated Mosaic audience, of five elections over the course of just several years, and the slow-running crisis in Israeli democracy which has accompanied that. And that, I think, is an underemphasized explanation for some of the political troubles we face in recent times.

Ben-Gurion, I need to look more into this, but he was a partisan in many respects of Anglo-American institutions, particularly British parliamentary institutions, because he saw that they provided necessary governmental strength. He was able to stop the development of a written constitution. He wasn’t able to carry off another one of his priorities, which was to bring in a first-past-the-post government, which he actually tried to do. I mean, there’s some debate amongst scholars, how serious was this? But in the Mapai party platform of 1955, it’s an incredibly clear articulation of the importance of moving, of dividing Israel into a “We’re going to make a representative territorial democracy here rather than proportional representation, what the Germans have.” Interestingly, that had been a priority of the right before it became something that Ben-Gurion tried to advance.

He didn’t succeed on that front, but if you ask me, this is something we’re going to have to look at in the years ahead. I wasn’t completely opposed to all kinds of judicial reform, but my frustration regarding political developments was, “Okay, if you have one bullet to shoot in terms of major institutional reform, it should be on parliamentary reform. Look at this. How can we have a situation where we have election after election, in which no durable governments are produced. Where a prime minister can be—not naming any names—but a prime minister can be declared who leads a coalition that none of his voters actually sought. I mean, there’s something broken there, and the way to fix it, again, there are all kinds of proposals. I myself am a partisan of strict first-past-the-post. I think it can be done in Israel. But either way, the parliamentary institutions of the country will need to be strengthened at some point.

Jonathan Silver:

Okay, so we’re already a bit over time, but I want to pose one final question to the three of you. Another question drawn from the many excellent questions we have from the audience, which has to do with the integration of the Haredi population in Israel. One of the famous bits of Ben-Gurion’s mythology is the original construction that set the pattern for the terms of the deal. And I wonder if, in light of the last many decades, you could think about that. I suppose the way that I would ask the question is, is the jury still out, such that very recent developments in the Haredi population and its movements toward integration both in the military and in the economy, do they suggest, after all, that Ben-Gurion may have seen something which has not been manifest over the last 70 years, but which may yet prove his insight?

Neil Rogachevsky:

Yeah, Ran or Avi, why don’t one of you guys take that one?

Avi Shilon:

Well, I think that there is no question that Ben-Gurion was among those people who believed in the secularization thesis. That the world is moving into a secular age because of science and rationality, and he thought that this is going to dismiss only 400 people from serving in the Army. He also didn’t want to find himself in a cultural war while the Israeli society is just being building with different kind of Jews from different areas of the world. Ben-Gurion in his later years said that he believed that the Haredi society will be much more integrated into the Israeli society. I do think that this is the main important process that is happening. Even though on the political arena it might be seen differently, in the real Israeli society, you can see much more integration between the Haredi and the secular. Even moreover, you can see much more seculars adopting Jewish religion and much more Haredim adopting themself into the secular Israel society. So in this term, I think that if Ben-Gurion paved the way, he was correct.

Jonathan Silver:

Ran, how do you see things?

Ran Baratz:

Yeah, so I have many Haredi friends, and we have deep discussions about this. Sometimes they sound optimistic like Avi in that sense. Of course, Avi is right that Israel is becoming more traditionalist. Not religious, but traditionalist. However, I’m a numbers guy, and the numbers don’t add to much. There is a process, it’s slow, and the rates are insufficient when you compare them to the rates of the growth of the population. Meaning that much of the Haredi society is still not integrating, and I would say even the major part. Of course, when it comes to policy, and this is where we go back to Ben-Gurion, I think the incentives are all wrong. The incentive of Israeli governments both left and right are all wrong when it comes to the Haredi. The major breakthrough was after the 2000 economic crisis, where the incentive structure was changed when Netanyahu was finance minister, and under Sharon, as Neil mentions in his essay.

We had a major breakthrough in participation in workforce, mostly of Haredi women, but also Haredi men. So I think it’s solvable. I think the hostility is a consequence of politicizing the cultural and social questions. If you depoliticize those questions, Israeli society today is much more susceptible to integrate with Haredi and Haredi. But you have to take the government out of the equation in order for the social incentives to kick in, and economic incentives to kick in, instead of the political incentives of fighting over it in the Knesset. So I’m optimistic if here we’ll be more Jabotinskian and less Ben-Gurionite, if that’s the way to say it. If we have a more limited government approach to the Haredi question, I think we’ll see more integration and a different kind of Israel will emerge. This is my hope, but my hope is a little bit shattered by the politics that make the Haredi question more politicized instead of less politicized.

So I don’t know where we’re heading, but I think here Ben-Gurion was—this is a kind of an old kind of realism. This is an accusation against realists that they don’t see culture and they don’t see religion. They neglect those aspects of social life, and I think here, Ben-Gurion might’ve missed that. That actually, Haredi Jews are experts in not assimilating, and this is not going to happen as easily as you would’ve thought. I will end with that. I have a Haredi friend who said the socialists wanted a socialist incentive structure for workers, but they made the best incentive structures for closed Jewish Haredi communities instead of for workers, which is an irony of history. But again, I think it’s solvable, but we’ll have to change our political approach to the issue.

Jonathan Silver:

Neil, on this and anything else, I want to give you the last word.

Neil Rogachevsky:

Yeah, so just follow up, I agree with much of what was said. Just to state the obvious point, Israeli history, major wars have been followed by massive social change. So we can highly expect many things that are very hard even to map out now to develop in the coming years. I think this bears directly on the Haredi question, right?

You mentioned this earlier, Jon, that the economic demands on the state are going to be immense. They are now, just the cost of keeping troops in the field. I mean, Israel skated through the last global financial crisis, the hard economic times of the past. It seems unlikely that this will happen in light of the war. And Israel’s welfare state, if you look at it, is actually smaller than one thinks. Transfer payments to Haredis and others form a large part of that, and it seems to me that in light of difficult economic times ahead, that will be something that any government would have to look at. Just here projecting again, we’ll see how it works out politically, there will be some, I would suspect, political support for dropping the stipends or, as Ran might put it, changing the incentive structure for Haredi men to join the workforce and other things. So there may be, actually, some opportunity there.

Jonathan Silver:

Well, a prudent government that commands Israel at that time will have to weigh the trade-offs between economic prosperity, the consequences of industrialization in Israel, and also important moral questions. In weighing those trade-offs, that’d be an awfully mamlakhti way to think about things. Neil, for giving us this tremendous essay and for generating this discussion, we’re grateful to you, as we are also grateful, Avi and Ran, to each of you. With that, we adjourn.

More about: David Ben-Gurion, Mosaic Video Events, statesmanship