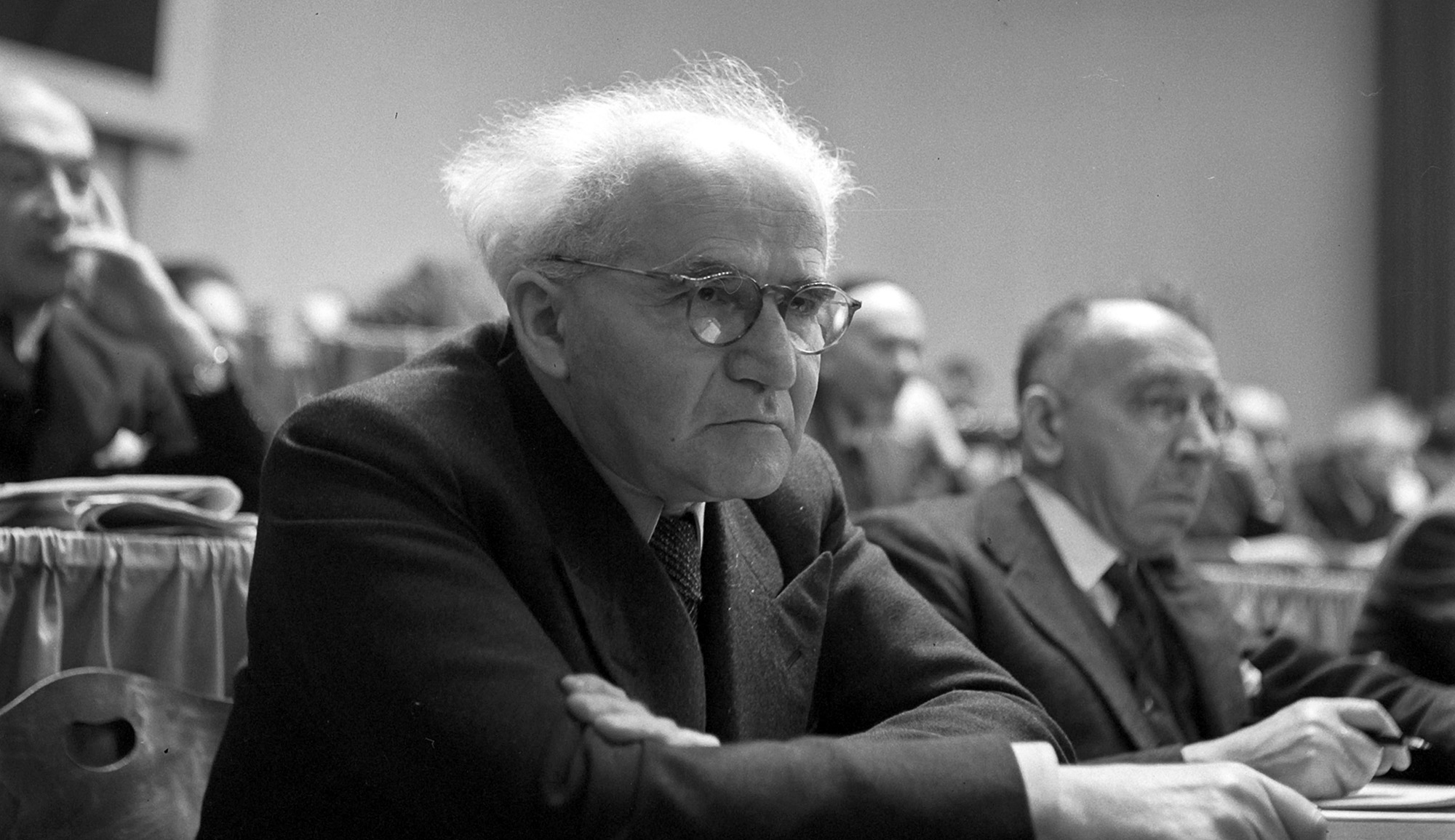

David Ben-Gurion died 50 years ago, December 1, 1973, at the age of eighty-seven. He lived just long enough to see the state survive the Yom Kippur War, its “most serious and cruel war,” as he described it in one of his final notes. He had been in reasonably good health until he suffered the first of two strokes a few days after the outbreak of the war. A doctor who examined him after the stroke later recalled encountering “an old and weary lion.”

Though he had often threatened retirement (and left the premiership briefly in the mid 50s), Ben-Gurion’s final retirement had been short. Like many of the best (and worst) leaders, he had great difficulty surrendering power. In 1965, he was essentially expelled from the Mapai party (the precursor to today’s Labor) after he attempted a rebellion against Levi Eshkol, who had replaced him as prime minister two years prior. He resigned from the Knesset for good in 1970, only three years before he died.

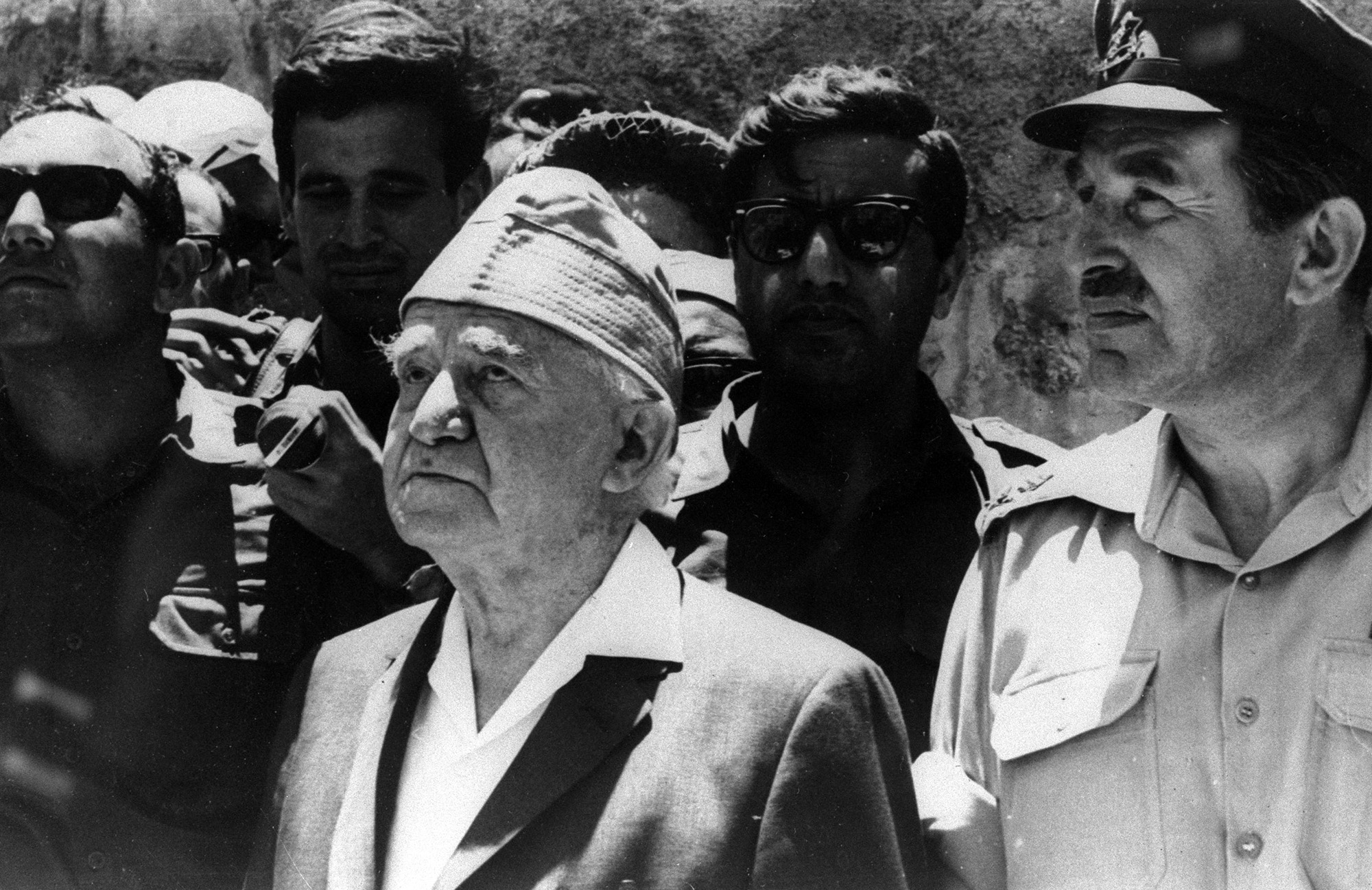

Excluded for the first time in three decades from leadership, Ben-Gurion in these last years remained engaged politically. After the triumph of the Six-Day War, he called for proactive policies to turn the military victory into a political one. According to his plan, Israel would annex the whole of Jerusalem; as for the remainder of the territory conquered from Jordan, Ben-Gurion advocated for an Israeli security zone along the Jordan River and negotiations with local Arab leaders over control of the rest of the West Bank. He had long seen Gaza as a source of instability. Shortly after the Suez War of 1956, he predicted that “the Gaza Strip would be a source of trouble as long as the refugees had not been resettled elsewhere.” Having conquered a then-much-more-sparsely populated Gaza from Egypt, he urged relocating some number of refugees to the West Bank—if they agreed. (Israel would formally annex the eastern neighborhoods of Jerusalem in 1980; no other aspects of this vision came to fruition.)

Ben-Gurion was even busier intellectually: reading, writing, carrying on epistolary dialogues with statesmen, philosophers, Bible scholars, Jewish thinkers. Joseph Stalin famously subjected terrified Politburo colleagues to mandatory drunken viewings of cowboy movies at his Kuntsevo dacha in his final years. Ben-Gurion, by contrast, assembled somewhat bemused or bored associates and scholars for Hebrew Bible study at his Negev cabin in Sde Boker. Ben-Gurion’s reading groups were not merely an expression of vanity or antiquarian curiosity. If Israel was to continue to succeed, he explained in 1968, Israelis needed to be “an exceptional people with an exceptional government.” The Jewish state had been created. But what would its purpose be? Much more work on this question remained. And, he thought, the political and ethical ideas of the Hebrew Bible were the necessary starting point. “I drew all of my humanitarian and Jewish principles from the Bible,” he reflected in a late interview. In his experimental disquisitions on biblical politics, prophecy, and law (most of which are collected in a 1972 English volume called Ben-Gurion Looks at the Bible), Ben-Gurion tried to articulate how biblical ideas might be deployed and recast for a new era of Jewish history—one defined by political sovereignty.

The 50th anniversary of David Ben-Gurion’s death, coming as it does amid Israel’s most grievous challenge since 1973, presents an altogether fitting occasion to reflect on Ben-Gurion’s statesmanship and the lessons it might present today. It would be folly to draw specific policy prescriptions from any human being who died half a century ago. But the key principles of his statecraft may rather serve as a source of both inspiration and insight as Israelis navigate the challenges of a post-10/7 world.

To be sure, other models of Israeli statesmanship resonate now too: Herzl’s argument for the necessity of Jewish sovereignty, Menachem Begin’s embodiment of loyal opposition, Levi Eshkol’s single-minded devotion to building Israel’s political and military capacities. But no other leader did more to shape modern Israel than Ben-Gurion. Creator of the nation’s government structure, principal author of the Declaration of Independence, first commander in chief, prime minister for most of the country’s critical first fifteen years, molder of the national culture, Ben-Gurion was Israel’s Washington, Jefferson, and Hamilton in one. He was indispensable in the establishment of the state, and he laid the foundations for its survival and success. Anyone who wishes to understand modern Israel and how it ought to govern itself must inevitably reckon with the rebellious man from Plonsk. In his early years, he later recalled, he was on the path to becoming one of the “dangerous young men” who would ultimately set the Russian empire aflame. Instead, he decided “to make the revolution within himself.” And he thus became, in the eulogizing words of Israel’s fifth president, Yitzhak Navon, “the most significant Jewish political leader since antiquity.”

I. The Standard of Statesmanship

Quizzed in September 1948 about the absence of the word “democracy” from Israel’s Declaration of Independence, Ben-Gurion denied this meant Israel would not conduct its politics democratically. He had not used this word, he said, because he wanted to express substantive political principles in Hebraic terms: “As for Western democracy, I’m for Jewish democracy. ‘Western’ doesn’t suffice. . . . The value of life and human freedom are, for us, more deeply embedded thanks to the biblical prophets than Western democracy.” It is worth noting that expressing universal ideas in a native vernacular has been an obsession of many statesmen of the first rank. Winston Churchill recalled that in his great wartime speeches, he would always opt for an Anglo-Saxon derived word rather than a Latinate one where possible.

This taste for Hebraic concepts and neologisms makes understanding his political thought fraught at times, no more so than with the label he essentially invented to describe his ideas: mamlakhtiyut. What is mamlakhtiyut? Literally translated as “state-ism,” scholars puzzle over its meaning to this day. It is also a difficult term to translate: “grandeur,” “state consciousness,” and “civic virtue,” have been tried. Though perhaps more redolent of Greek than Hebrew, my own preferred translation is “statesmanship,” which refers to the peak political virtue that a human being can attain. It speaks to an ability to understand the whole political scene, at home and abroad, and to act prudently to advance the interests of the state and its community. Mamlakhtiyut is the Hebraized articulation of the same human capacity that Aristotle called phronesis, simultaneously the precondition and consummation of statecraft.

To define it further, we could do with Ben-Gurion’s own explanation from a 1952 essay (recently cited in Mosaic by Philologos):

We have brought with us from the Diaspora anarchic and disintegrative habits—a lack of mamlakhtiyut, of national solidarity, and of the ability to distinguish between the essential and the trivial, the permanent and the passing. In renewing its independence, the Jewish people has to confront two encumbering traditions: its problematic sense of mamlakhtiyut in antiquity and the anti-mamlakhtiyut of exilic existence.

Mamlakhtiyut is the essential quality of national self-government, and its opposite is what typifies Jewish statelessness. Like some political Zionists before him, Ben-Gurion argues that the Jews of exile had internalized a lamentable apolitical or even anti-political ethos. While the Jews had produced important works of humane learning during exilic times, this ethos left them largely defenseless against military threat, intimidation, and outbreaks of violence. For Ben-Gurion, this was an intellectual as much as a practical error, because politics are inescapable. Perhaps the wise men of Israel, and through them some of the people at large, might have maintained a healthily ironic attitude to worldly politics. Utter contempt for politics could however make them numb to important human possibilities. And it also made them vulnerable, unable to protect the rich intellectual heritage they valued so much. As Ben-Gurion put it in a letter to the Zionist agriculturalist Menachem Ussishkin, the Jews could create a university in exile but did not know the first thing about running a state:

The few sages who could see into the future . . . understood the importance of saving “Yavneh and its sages.” “Yavneh and its sages” are important, but they do not constitute a Jewish state. And did we come over here, the people of BILU [a late 19th-century Zionist movement], the members of the Second Aliyah and the New Aliyah, to build in this country “Yavneh and its sages?” And under the auspices of the mufti?! We want to build a state, and we shall not be able to do so without political thought, political talent, and political prudence. High-flown phrases, vision, and emotion alone are not sufficient to build a state; they may be sufficient for Netsah Yisrael, or existence in the Diaspora, for maintaining a yeshiva, a rabbinical court, a university—but not for the construction of a state.

The Jews of antiquity offered an encouraging alternative model. These Jews had the experience of political sovereignty. Ben-Gurion’s turn to the Bible was, above all, an effort to find wisdom about prudent political action from within the Jewish tradition. Ben-Gurion also drew a cautionary lesson from ancient Jewish politics. The Jews of ancient times had been especially susceptible to political schisms, which had been caused largely by theological and doctrinal divides rather than the purer class conflict that plagued other ancient polities. Inevitable differences in the understanding of man’s relationship to God had led to bitter factionalism among different Jewish orders or sects. In Ben-Gurion’s view, political schism rooted in religious division was the reason Jewish sovereignty had been so short. As he continued in his 1936 letter to Ussishkin:

During the time of the First Temple we did not conquer the entire country, and we maintained our independence only for a few years because we were always divided and quarreled among ourselves, and the nations around “ate us with every mouth.”. . . The legions of Rome would not have destroyed the country if the Jews had not prepared the ground for it. At the time of the gravest danger in our history, before the destruction of the Second Temple, the Jews did not know how to unite, did not identify the external dangers, and did not find in themselves the political talent to prevent the catastrophe, which would have been averted if such a talent had been found in the Jewish people at that time.

Political skill, awareness of dangers both manifest and latent, seeing the interests of the country over and above mere sectarian interests—these were the traits the Jewish state would have to embody. Achieving it would require national unity, respect for laws and institutions, a sense of civic obligation and service. Israel would thus require a civic culture that would inculcate these traits in its citizens.

To be sure, Ben-Gurion—and the Labor movement that led the country from its founding until 1977—did not always act in accordance with this concept. Indeed, both probably damaged the reputation of mamlakhtiyut by implementing it in particularly partisan ways. To cite the most famous example: the erstwhile militia leader Menachem Begin, whose movement had broken away from mainstream Zionism, accepted the legitimacy of the state of Israel in 1948. His Revisionist Herut party worked to advance its vision of Jewish statehood from within the framework of the state. Despite this essential contribution to mamlakhtiyut, Ben-Gurion could not bear to address Begin by his proper name, and he sometimes equated a vote for Herut with a vote for national dissolution. Later in life, he admitted he had been too hard on his rival. In 1969, soon after his wife Paula’s death, he told Begin in a letter that Israeli history would have been different had he judged Begin more honestly: “the better I have come to know you in recent years, the more I have come to admire you, and my Paula was very happy about that.”

One sees Ben-Gurion’s undeniable instances of partisan myopia in a different light when one recalls what the alternatives were. As the historian Avi Bareli has shown, some of Ben-Gurion’s fellow labor leaders went so far as to stress the “unity of the party and state,” as East European Communist leaders did. “Mapai is Zionism,” said one of Ben-Gurion’s Mapai party colleagues in 1949. But overall, Ben-Gurion’s record of statesmanship stands up well. As prime minister, Ben-Gurion managed to balance the need for a strong state with respect for political, religious, and ethnic differences. Ultimately, he understood the state would be stronger precisely if it respected the rights of citizens.

II. Culture War and the Spirit of Compromise

For Ben-Gurion, a key plank of mamlakhtiyut was aversion to culture war. When the various “Who is a Jew” controversies erupted in Israel in the 1950s and 1960s, his response was to convene a diverse array of Jewish experts around the world to write learned essays on the subject, rather than to press for political action. While some Labor-movement colleagues in the first years of the state sought to create a single, uniform national education system that would aspire to turn new immigrants into labor Zionists, Ben-Gurion successfully advocated for educational pluralism.

In other words, he refused to make war on the cultural traditionalism and religiosity of new immigrants from the Middle East and North Africa. National service and patriotism were essential to inculcate across sub-cultures of Israel. But culture war, especially on religious and constitutional matters, was simply dangerous. If a small state like Israel devoted itself to culture war, it would tear itself apart before its enemies could. In a highly significant speech to the Knesset in 1949—Mosaic published the translation in 2021—Ben-Gurion cautioned against culture war and urged a muddling-through approach to thorny questions about religion, state, and the nature of the regime. He warned also against debating the chief question on everyone’s minds, of whether Israel should establish a formal constitution. Such a debate would

embroil most of the members of the Knesset, and of course the newspapers—Ma’ariv and Y’diyot Aḥronot surely. The matters are maybe important, but they’d instigate a fight and an argument. . . . If we begin to engage in major philosophic arguments, we will damage the essential needs of the state.

A religiously and intellectually diverse nation had to leave the deepest questions partially unresolved if everyone were to live together tolerably. Surrounded by enemies, Israel had to concentrate instead on building its political and economic might. The Jewish penchant for intellectualism and theory, while a source of strength, could be debilitating if it absorbed too much political attention. “We very much love theoretical debates,” Ben-Gurion continued in the same speech: “One person will declare allegiance to Israel, another to socialist revolution. A third will say he’s loyal to popular democracy, and another to pioneering. It’s a divisive and futile debate . . . and it will distract us from the essence of the matter.”

The “essence of the matter” is political. Questions of war, peace, and diplomacy had to be front and center for ordinary Israelis, to say nothing of the political class. And the political class had to be perpetually interested in “foreign threats”—a subject that involved not only understanding how Israelis saw the world but also how other powers viewed Israel.

In his early years, Ben-Gurion had a much narrower sense of geopolitics than some of his far-sighted contemporaries. The Revisionist leader Vladimir Jabotinsky clearly saw that the Ottoman empire was on its last legs before World War I and thought that the Jews of Palestine had to throw in their lot decisively with Britain. Ben-Gurion saw later than Jabotinsky did that Arabs would not surrender their own political agenda if given various economic benefits by the Zionists. By 1948, however, his domestic and international vision far exceeded that of his colleagues and rivals. Just before independence in 1948, some left-wing Zionists like Moshe Sneh and Yaakov Riftin gave speeches denouncing “Anglo-American imperialism” and implicitly calling on the Jews of Palestine to align with the Soviet Union. Broadly comprehending the relative power of England’s newly diminished role in world affairs, and the strategic orientation and capabilities of the unfolding cold war, Ben-Gurion saw the situation more clearly. The British would reinforce their Jordanian allies, but they would not launch an actual invasion of the Jewish state.

Meanwhile, he saw that the state would have to engage in a fragile balancing act between the Soviets and America—even as, very early on after independence, he subtly began to turn Israel toward the West and away from the Soviet Union—though even here Ben-Gurion always attempted to maintain maximum freedom of action for the Jewish state This meant, as a full essay on Ben-Gurion’s generally brilliant foreign policy would demonstrate, taking friends where he could find them. Completely boycotted by the Arab world in the 1950s, Israel looked further afield for allies, to Iran and many African states. Formally subject to an American arms embargo, Israel reconciled with its former colonial master Britain, and developed strong ties with France as well.

Though political exuberance sometimes overtook him, he saw it as the responsibility of the statesman to be keenly aware of real and potential dangers around the corner. After Israel’s victory in the Six-Day War, Ben-Gurion was overwhelmed by “profound joy,” he wrote some time after. “I experienced something as profound only on my first night after arriving in Petah Tikvah, when I heard the howling of the jackals and the braying of the donkeys and I felt that I was in our nation’s renewed homeland, not in exile.”

In general, though, he felt that it was the responsibility of statesmanship to guard against undue optimism. “I mourn amidst the rejoicers,” Ben-Gurion wrote in his diary both after the UN had approved the partition of Palestine into Jewish and Arab states on November 29, 1947 and after he declared independence on May 14, 1948. He anticipated the dangers to come. During World War II, he studied Churchill’s great speeches carefully. He especially admired that Churchill could share “bitter truths” with the British people. Fear of evil, Ben-Gurion believed, makes a sounder basis for policy than hope.

III. Economics and the Spirit of Sparta

On economic matters, the mature Ben-Gurion balanced pluralism with a martial austerity that complicated his attitude to national wealth and development. He held conventional labor-Marxian beliefs in his early years in Palestine, to which he made his way from the Russian empire in 1907. But as he rose through the ranks of the Zionist leadership, and certainly by the time he began to take the reins of Palestine-based Zionism in the 1930s, his ideological rigidity had waned. His lodestar became a strong Jewish state—and he was willing to countenance whatever economic policies he thought would strengthen the state. He retained a lifelong commitment to the idea of pioneering and of settling all the land—pillars of the labor movement. In the 1950s he still would speak of inculcating the “pioneering spirit” in newcomers to Israel. But as prime minister, he never seriously attempted to stifle the growth of a more “bourgeois” mindset and lifestyle in Israel’s larger towns and cities. Those lacking the Histadrut union “red card” would face economic discrimination for decades.

If not for Ben-Gurion, however, many Mizrahi Israelis may not have come to Israel in the first place. In 1949, the Mapai party flirted with immigration restrictionism partially because of the immense economic strains on a country that had just barely emerged from the War of Independence but also, just as importantly, owing to prejudice that Mizrahi Jews were somehow unfit for the pioneering life. Ben-Gurion fought against this narrow Labor parochialism. Israel desperately needed Jews. These Jews needed Israel. With the passage of the Law of Return in 1950, Israel essentially opened the door to cultural and economic diversity even as economic statism remained the dominant economic paradigm until the 1980s.

Despite this commitment to de-facto economic and cultural pluralism, Ben-Gurion also sought to model austere virtue for generations of Israelis. He had moved to the Negev kibbutz of Sde Boker in 1953—before air conditioning—hoping to set an example of continued toil and struggle for the coming generations. Austerity was a common social as well as ideological marker of the labor Zionist elite. And whatever tastes they may have had, they arrived in an early-20th-century Ottoman Palestine which was among the poorest regions in the world. The rustic and simple lifestyles of David Ben-Gurion, Golda Meir, Levi Eshkol, and Moshe Dayan set the tone for Israel’s entire political class, left and right, well into the 1990s.

Behind this seemingly superficial stylistic matter was a salient insight about the potentially corrupting effects of wealth on civic virtue, an insight that writers ancient and modern had addressed. Though ultimately necessary to perpetuate the state, the drive toward the limitless accumulation of wealth at the same time risks producing beliefs and habits that can endanger the state. In the 20th century, writers such as Raymond Aron, Irving Kristol, and Daniel Bell similarly analyzed the “cultural contradictions of capitalism.”

Ben-Gurion did not live to see Israel become prosperous. Yet he worried that cultural and economic laxness could lead to civic decline. And on some matters, he was willing to use law or bureaucratic means to restrict practices that might damage the national spirit. It was David Ben-Gurion who ensured that the “useless” color television did not make its debut in Israel until 1983. In 1965, the Mapai party banned the Beatles from playing in Israel for fear of corrupting the young. (Paul McCartney would ultimately play in Tel Aviv’s Yarkon Park in 2008 to great adulation). It was this aspect of early Israel that led perceptive commentators to compare the Jewish state to ancient Sparta.

IV. Has Israel Lived Up to Ben-Gurion’s Ideal?

Really existing states rarely stand up to the exalted visions of their creators. Israel is no different; few Israelis, at any time, would describe its politics or daily life as fulfilling Ben-Gurion’s ideal of statesmanship. But understood at the most basic level as commitment to the country, mamlakhtiyut has been an extraordinary success. After elite flirtation with post-Zionism in the 1990s and 2000s, today both elite and ordinary Israelis are invested in the future of a Jewish state, even as they differ, sometimes radically, about what a Jewish state ought to mean. In moments of crisis, political figures and the nation at large have been able to put the cause of the state above partisan distinctions or personal political fortunes. On October 6, opponents and supporters of judicial reform were having a caustic war of words at Shabbat tables and on the streets. On October 8, they were ready to fight together as brothers-in-arms in Gaza.

Indeed, national service remains robust: witness the return of reservists in numbers from abroad immediately after October. Druze and Arab-Israeli citizens have contributed both on the battle front and home front; a recent poll indicating that 70 percent of Arab Israelis identify with the Jewish state is powerful reason to believe in the Jewish and liberal aspirations of Israel’s founders. (In the early days of the war, the papers were full of heartening stories of young ultra-Orthodox men enlisting in the army. This seems to have tapered off, and ultra-Orthodox enlistment may reemerge as a radioactive political issue when the fighting stops.) The national war slogan, “together we will win,” speaks to an actual national consensus in favor of winning, though there has been minimal public debate about what winning might mean. The nationwide mobilization and solidarity displayed since 10/7 should dispel any notion that Israel is weak because it is politically divided, soft, or distracted.

Still, other aspects of mamlakhtiyut have either declined in recent times or simply never took hold in the first place. Ben-Gurion hoped Israelis would develop “respect for law and institutions.” This has been a mixed success at best. The Israeli state has often been strong. It has known its share of imaginative and effective bureaucrats. But government, bureaucracy, and courts have often been seen as unresponsive, unrepresentative, and ideologically biased. Government and parliament have often been weak, and the quality of the political class has declined over decades, so that now the weakness of Israel’s current leadership is widely accepted.

All of this was bad enough in peacetime. During the war, many Israelis have expressed, with some justification, that feel abandoned by a government still driven by narrow personal ambitions and partisan score settling. Even longtime admirers have been disappointed by Benjamin Netanyahu’s reluctance to take responsibility for what happened on his watch. Despite the national emergency, Finance Minister Bezalel Smotrich has continued to deliver large transfer payments to favored groups and constituencies rather than redirecting funds to the war effort. And by not forcefully acting against vigilantism in the West Bank, and by repeatedly urging the permanent transfer of Gaza’s civilians, parliamentarians like Itamar Ben-Gvir have failed the basics of not only mamlakhtiyut but of liberal democracy, according to which the state alone is responsible for justice. On the left, there have been many who are all-too comfortable to enlist the U.S. government and foreign NGOs in domestic political battles, a dangerous affront to national sovereignty and Israel’s freedom of action.

Above all, Israel’s descent over the last handful of years into all-out culture war represents perhaps the most flagrant deviation from Ben-Gurionite mamlakhtiyut in Israeli history. It has been a massive failure to follow his dictum to distinguish “the essential from the ephemeral.” At the time, the battle over judicial reform may have seemed like a debate over the most essential matters in Israeli public life. In hindsight we can see it for what it was: a terrible national distraction. (That such a debate could be considered a distraction just goes to show how difficult it is to distinguish the essential from the ephemeral.) For whatever one’s position on the authorities of the Supreme Court, it hardly represented an imminent threat to the safety, security, or flourishing of the state.

In a tragicomedy of errors, Israelis persuaded themselves that the future of the Jewish state hinged on the reasonableness standard in judicial review. The national debate frequently got lost in trivialities, such as whether bread products should be allowed in hospitals on Passover. One cost was the ripping apart of a difficult but tolerable truce between the different parts of Israeli society to the point that many feared serious violence; a prominent Israeli politician told me recently: “Had October 7th not occurred, there would have been blood in the streets, shed by us.” Another cost was even worse: matters more truly relating to life and death—normalization with Saudi Arabia, the growing threat of Iran, and, as it turns out, the capacities of Hamas—were placed out of sight, out of mind.

Unfortunately, the reform debate may not be over. On January 1, the Supreme Court canceled the government’s law rejecting the Court’s power to invoke the reasonableness standards in rulings. At the same time, it claimed for itself the power to overturn Basic Laws if, in the judgment of the Court, the law does not conform to Israel’s Jewish or democratic character. This ruling could either be the end of Israel’s recent experiment with judicial reform or else set the stage for an even more intense fight after the war. In either case, one hopes that the experience of the last year will lead protagonists to think twice about putting the country through another bout of civil conflict amid so many foreign-policy dangers.

Why did this cultural and constitutional showdown break out now? I have written elsewhere that the judicial-reform crisis is really a species of Israel’s parliamentary crisis stretching back half a decade, as the country absorbed election after election without clear results and the legitimacy of politicians and the system itself came to seem doubtful. But another factor was at work too. Before 10/7, Israelis felt far more at ease than in many decades, perhaps than ever before. A streak of utopian thinking of both left- and right-wing varieties gripped Israelis in the almost two-decade period of relative calm following the Second Lebanon War in 2006. Many centrists came to think that there were technocratic solutions to every political problem. The state-of-the-art security fence could almost make one believe that Israel really had “disengaged” (Ariel Sharon’s term for his withdrawal in 2006) from Gaza. Some on the right thought that the government’s successful blocking of an unworkable two-state solution with the Palestinians meant Israel now had a free hand to do what it liked in the West Bank and elsewhere. And the small remnant of the Israeli left continued to dream that peace was simply a matter of everyone willing it.

This kind of utopianism was enabled by economic trends in Israel that go back decades. Israel is no longer Sparta, and it hasn’t been for a while. Both color TV and economic liberalization were relatively late to the game in Israel, but the cultural and economic changes they wrought were enormous. In 1984, the Ben-Gurion protégé Shimon Peres enlisted the young MIT economist Stanley Fisher to restructure a dysfunctional economy that saw 450-percent inflation in 1984. Under Fisher’s economic stabilization plan, banks were privatized, and state expenditures cut. The first of several efforts to diminish the power of the Histadrut labor union was launched. The liberalizing reforms were later advanced adroitly by Benjamin Netanyahu during his tenure as Ariel Sharon’s finance minister from 2003 to 2005.

Sound economic policies and global economic developments combined in Israel to produce a run of astounding economic growth, which really got going after the second intifada (2000–2005). Israel sailed through the global financial and Eurozone crises that marked the end of the first decade of the century and began to experience the benefits of having its highly educated workforce link up with foreign firms and capital. This was the zeitgeist captured by Dan Senor and Saul Singer’s Start-Up Nation. Some Israeli academics wondered whether their country had become fundamentally “bourgeois” or middle class.

It would be too simple to say that Ben-Gurion would have opposed this development in Israeli society. Indeed, at the time of Ben-Gurion’s death in 1973, his fears about money may have seemed obscurantist. Why worry about the moral effects of wealth or luxury when there was so little wealth or luxury to go around? In the aftermath of the Yom Kippur War, Israel saw dramatic decline in economic growth and rising inflation, after steady and sometimes dramatic growth in the 1950s and 1960s. There was to be no quick recovery. The combination of rising military expenditure and welfare-state transfer payments finally brought the economy to its knees during the second part of Menachem Begin’s premiership, in the early 1980s. The structural reforms of the mid-1980s helped stabilize the situation, but Israel at the turn of the 21st century was hardly rich, and what wealth it had was not consumption-driven.

When I first visited Israel some quarter-century ago, owning a private car was considered a luxury. Most Israelis still took their post-army long trip but the frenetic travel around the world we see today was unheard of even for the well to do. Keeping in touch with friends and relatives abroad by long-distance phone call was a serious expense. That charming if dilapidated apartment in the center of Jerusalem or Tel Aviv could have been had for a song in the early 2000s; now it would fetch Manhattan-level prices. Though ubiquitous national and military service still mitigates against this, the question of the moral effects of wealth has become relevant in a country whose GDP now rivals that of some European countries.

As recently as the 2000s, Israel could reliably count on a large share of its best and brightest staying in the army or other public-sector jobs. The explosion of the tech sector changed all that. In the last fifteen years in particular, start-up nation has meant higher income and more interesting life opportunities—like making the color TV shows that are now among Israel’s chief cultural exports. The result has been that Israel’s best and brightest could exercise their talents beyond the military and the political spheres. Indeed, the most coveted military assignments are now in cyber-units that prepare their veterans for business opportunities afterwards.

No one would wish for Israel to be poorer. One lesson from the classical literature on the dangers of wealth is that states must pursue as much national wealth as possible, without limit, if they have any hope of competing with other states that inevitably will do the same. Yet the blessings of Israel’s newfound wealth have fed a deeper problem.

V. Normaliyut and the Return of Statesmanship

Perhaps the opposite of mamlakhtiyut is the English-derived word normaliyut, normalcy. Widely used in the country since the 1990s, it connotes a wish to lead normal lives after all the travails of the Jewish and Israeli past. This desire is natural. Yet, fed by economic and cultural success, over the last couple of decades it grew into something of a seductive fantasy—a belief that Israel had become a high-tech utopia living in the so-called “End of History,” or at least had become strong and powerful enough that it could afford to view life and politics through cultural or spiritual lenses rather than political ones. For despite the growth in prosperity, despite the Abraham Accords and other regional breakthroughs, the dangers were there all along. Now that they’ve been revealed, normaliyut will have to be put on hold yet again.

As the war continues, there are signs that some Israelis are replacing the desire for normalcy with a steely mamlakhti resolve. Asaf Zamir, the former consul-general in New York, recently summed up Israel’s grave challenge in language that could have been ripped from David Ben-Gurion:

If this war ends without it being completely safe to return to live on the border of Lebanon, and around Gaza, and if it’s impossible to return and hold festivals and events in the entire country without any fear, we lost. Not the war, the country. Want to know what the goals of the war are? These are the goals of the war. No less. Otherwise it’s over. Maybe slowly, but over.

Some prominent politicians have made substantive expressions of national solidarity. In the first days of the war, the former prime minister Naftali Bennett volunteered near the front, packing supplies. The fact that Benny Gantz, now a minister in the emergency war cabinet, named his party the Mamlakhti Camp likewise indicates that the concept retains at least rhetorical power, and perhaps even political force. In mid-December, Gantz announced that he is moving to the western Negev, clearly attempting to follow in Ben-Gurion’s footsteps. Ben-Gurion had moved to the arid region in the 1950s not only to exemplify the pioneering spirit but also because he knew that a civilian presence in the area was ultimately essential for Israel’s national defense: if Israel’s periphery wasn’t safe, its center ultimately wouldn’t be either. The stories of heroism and leadership from the front have been too numerous to count. And who can now say what future leaders are at this moment being formed on the battlefield in Gaza and in the command rooms in Tel Aviv?

Ben-Gurion demanded a great deal from Israelis. As he put it in his final public Bible lecture:

We are the smallest of nations and, thus, we must be an exceptional people. Only our superior quality has sustained us. We succeeded in the Six-Day War because we succeeded in building an exceptional army. And we need not fear evil if we also succeed in establishing an exceptional government. The Jewish people has the needed traits to be an exceptional people, but to achieve this, more than any other nation in the world, we need an exceptional government.

Yet perhaps Ben-Gurion expected too much from his countrymen. Designing America’s government, the American founders soberly understood that “wise men will not always be at the helm,” and thus instituted a system of checks and balances to compensate for the inevitable failings of human nature and to channel human energies in constructive directions. Israel is not blessed with such a system. After the war, Israelis may be forced to examine ways the design of its governing institutions has failed to account for these failings and how it can be strengthened, though the bitter experience of judicial reform may forestall that task. In any case, even if Israel boasted exemplary institutions, it could ill afford a sustained run of mediocre leadership. Ben-Gurion’s mamlakhtiyut ought to be one cornerstone of an Israel that emerges stronger from this great test. Following the example of its indispensable founding father, the Jewish state must learn again to bear the burdens and embrace the splendors of statesmanship.

More about: David Ben-Gurion, Gaza War 2023, History & Ideas, Israel & Zionism, new-registrations