The story of the Jews was told so effectively in the Hebrew Bible that it shaped and sustained them as a people from that time to this. But what happens now?

We live in an era in which the Jewish people, having suffered a catastrophic national defeat greater even than the one recorded in the book of Lamentations, went on to write a chapter of its history at least as remarkable as any in its sacred canon. In a single decade, bereft of one third of their number, and without the obvious aid of divine intervention, Jews redefined “miracle” as something that could be enacted through human effort. Over the past six decades, the vitality and civilizing restraint of the Jewish way of life, honed in almost 2,000 years of exile, have been made manifest in the regained conditions of a thriving Jewish polity—one that simultaneously has been under relentless and, lately, spiraling pressure from all sides.

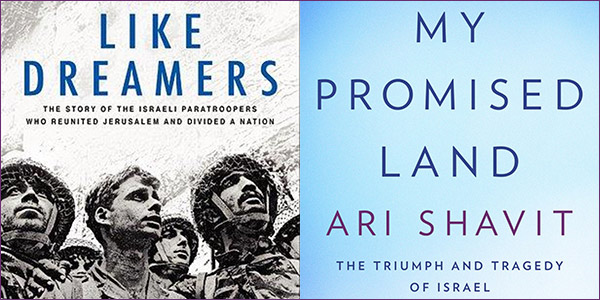

Will authors rise to this occasion as ably as the biblical authors did to theirs? Two recent and well-timed accounts of modern Israel offer a useful framework for examining how the challenge is being met. At over 450 pages apiece, each book required years of research and gestation: ten in the case of Yossi Klein Halevi’s Like Dreamers, five in Ari Shavit’s My Promised Land. So there is no question about the gravity of these authors’ intentions, or the definitiveness of their aims and ambitions. Those ambitions, moreover, have already been rewarded in the form of unfailingly warm, respectful, and serious attention in the American press—and in Shavit’s case by a place on the bestseller lists.

What, then, have they wrought?

Yossi Klein Halevi’s Like Dreamers: The Story of the Israeli Paratroopers Who Reunited Jerusalem and Divided a Nation traces the intertwined lives of seven men of the 55th Brigade of the Israel Defense Forces, which won back the Old City of Jerusalem in the 1967 Six-Day War. A brief introduction situates the author himself circa 1967 as a fourteen-year-old boy in Brooklyn. His father, a Holocaust survivor, is so shaken by the terrifying lead-up to war—many in those months feared a devastating cataclysm—but then so relieved by its outcome that he takes his son to see Jerusalem at first hand. Fifteen years later, the son, already a journalist, immigrates to Israel. One day, he is inspired by an article on a reunion of the 55th Brigade to look up the paratroopers, hoping to write about them on his own. As his project expands into a book, he is struck by a fascinating division among the men that suggests the main arc of tension in his burgeoning story: the split in outlook between secular Zionists hailing from the world of the kibbutz and religious Zionists hailing from the world of the yeshiva.

Except for continuing to treat his subjects as a unit, Halevi tries to stay out of their way and let them speak for themselves. The book is arranged chronologically, from 1967 to 2004, beginning with a detailed reconstruction of the battle for Jerusalem and then following the seven men at key intervals as they move into civilian life while also being drawn back repeatedly into their unit as reservists. A complicated grid, mainly unseen by the reader, weaves in and out of their intersecting lives, telling their back stories and highlighting their individual idiosyncrasies even as it connects them as a group to major historical developments over almost four tumultuous decades in their country’s life. In this way, above and beyond what we come to learn about each man, his family, his personal achievements and failures, we are shown the interdependency that persists among them as their attitudes, thoughts, and convictions play out in the context of an open society debating its future while under unremitting threat from without.

Ari Shavit’s My Promised Land: The Triumph and Tragedy of Israel is one man’s personal account, almost confessional in its intensity, of the history of his country from the arrival of a great-grandparent in 1897 to the writing of this book in 2013. It, too, is arranged chronologically. Its seventeen chapters trace the history of early Jewish settlement of the land, the growth of collective settlements (kibbutzim and moshavim), the advance of agriculture, housing, and scientific research, the early absorption of Holocaust survivors and expellees from Arab countries, and so on into the present. Each of these developments is situated in the geographical locations within Israel with which they are historically associated.

A fourth-generation Israeli, an influential columnist for the daily Ha’aretz since 1995 and a sought-after political commentator, Shavit writes with an insider’s familiarity, interviewing leading cultural and political figures as old friends who share a lifetime of assumptions and sometimes quoting his own previously published words as pithy statements on Israeli events and personalities.

In their contrasting approaches, the two books thus somewhat resemble the reportorial versus the editorial sections of a newspaper. That being so, it makes sense to begin with the one that reads like reportage, if of an extremely high literary order.

The photograph on the dust jacket of Yossi Klein Halevi’s Like Dreamers is of young, battle-exhausted paratroopers looking up at the newly won Western Wall of the Temple Mount in Jerusalem. In the center, the youngest of them, helmet in hand, will become an iconic image, epitomizing the fulfillment of God’s ancient promise: v’shavu banim l’gvulam, “Your children shall return to their borders” (Jeremiah 31:16). Israel’s reunification of Jerusalem, the culminating event in several months of apocalyptic tension and six days of ferocious fighting, released a sense of relief and joy unparalleled in the country before or since. It was something like this same sense of relief that Halevi was reaching for in 2002, at the height of the second intifada, when he began seeking out the veterans of that earlier battle to see what had become of them.

In 1967, about half of the soldiers and 70 percent of the officers of the 55th Brigade were the products of kibbutzim; a much smaller proportion was made up of religious Zionists. The two groups disagreed about such things as the place of religion in Israeli and Jewish identity, but Halevi finds an essential commonality in their animating idealism. “[For] all their differences,” he writes,” religious Zionism and the secular kibbutz movement agreed that the goal of Jewish statehood must be more than the mere creation of a safe refuge for the Jewish people.” Each side saw itself as laying the foundation of an ideal society—egalitarian in the one case, religious in the other, with the dominant form of utopianism being that of the secularists. In deference to their common zeal, he draws the title of his book from a passage in Psalm 126:

When the Lord returned the exiles of Zion,

We were like dreamers.

Then our mouths filled with laughter,

And our tongues with songs of joy.

Then they said among the nations:

“The Lord has done great things for them.”

The Lord has done great things for us.

Like Dreamers then follows these men from their dream state into daily life—much as paratroopers drop from the skies to land on unyielding earth.

Halevi relishes the evolving diversity of his cast of characters. Among those from the kibbutzim there will emerge a managerial genius who helps move the Israeli economy from statism toward capitalism; a songwriter who strikes out from the farm to the city; a sculptor whose large-scale installations harness the physical resources of his kibbutz; and an anti-Israel spy who joins a terrorist network and gives his handlers in Damascus whatever they want to know about his military training. (You read that right.) The distance each of these individuals seeks from the collectivist esprit of his upbringing helps to explain why the kibbutz as an institution had to give way to a society of greater freedom—and perhaps even why one individual would use that freedom to betray it.

Among the religiously devout, temperamental and intellectual differences also disturb the initial unity of purpose. Several after 1967 become leaders of the settlers’ movement, which for a time enjoyed the support of the Labor government and continues to be supported by much of the country at large. Here Halevi may be simplifying his story-line when he writes that “the Israel symbolized by the kibbutz movement became the Israel symbolized by the settlement.” For the religious men in the unit, as his narrative shows, it is less a case of symbolism than of adjusting, like their secular counterparts but in different terms, to the non-ideological opportunities and obligations of a dynamic society under siege; when it comes to the settlements, the same can be said for Israelis in general.

No surprise to those familiar with Israel’s history, soldiering occupies a prominent place in this book, sobering in the degree to which it holds these particular men in its grip. In America, only professional soldiers are called up for successive tours of duty. But, scant years after the battle for Jerusalem, the reservists of the IDF’s 55th Brigade were fighting again, in even more traumatic conditions, in the Yom Kippur War of 1973.

Then came 1982, when Israel undertook, in concert with Lebanese Christians, to drive the PLO out of Lebanon; during their second tour of duty that year, the battalion members could sense the eroding support of a country beginning to tire of ceaseless combat. Around the campfire there is talk of a colonel who has refused an order. Some of the men call him courageous, but a religious reservist invokes his eight-year-old son, according to whom it is permitted to speak against the government and forbidden to speak against soldiers—but also forbidden for soldiers to disobey an order.

“‘Why, Odi?’ I asked him. ‘Explain it to me.’”

“‘What will happen,’ said Odi, . . . ‘if there is a war and someone will say I don’t want to fight?’”

The reservist concludes, embellishing a rabbinic aphorism, “After the destruction of the Temple, prophecy wasn’t given only to fools but also to children.” A future generation of Israeli soldiers was beginning, at an early age, to balance civic and personal responsibilities in a democracy where the word of security officials was being subjected to doubt. In the decades after 1982, as Halevi demonstrates in his remaining chapters, the coils become only tighter, the conundrums more agonizing, opinion more polarized.

A reader whose taste I normally share told me this book left him dissatisfied. He kept losing track of the characters and had to keep thumbing back to the orienting “Who’s Who” at the front. I see his point, but nothing conveys the experience of daily life in Israel—where the boundaries between war and peace can be as permeable as those between Manhattan and the Bronx—better than Halevi’s back-and-forth between the contrasting yet contiguous spheres of battlefront and home front, secular and religious camps, collective and individual experience. By letting the men speak for themselves through interviews and memoirs, he also projects a feeling of unedited frankness and spontaneity.

The method works especially well in the case of the poet-singer Meir Ariel. In May 1967, just weeks before the outbreak of war, the popular Israeli songwriter Naomi Shemer had composed “Jerusalem of Gold,” expressing a longing for the Western Wall and the still-lost parts of the nation’s capital. Weeks later, King Hussein’s unanticipated attack on the Jordanian front, followed by victory in the resulting battle for Jerusalem, the song, with updated lyrics, turned into an anthem of reunification. Its patriotic fervor disturbed some on the Left. Drawing on his experiences in the city’s liberation, Ariel wrote an alternative version that he titled “Jerusalem of Iron,” registering the cost in the number of Israeli casualties (swollen by inadequate intelligence) and the lead needed to win that city of gold. Yet he insisted that his darker lyrics not replace but remain a commentary on the original song, and he declined to be lionized as a political protester.

Restive in the disciplining embrace of family and kibbutz, Ariel eventually drifted into religious life—not as a captive of any movement or party but on his own, looking for what he needed. Were Halevi a tendentious writer, he might have cast Ariel as the paradigmatic baal teshuva who “returns” to God and religion. Instead, we follow the unsteady path and tortured consciousness of a young man in an open society whose freedoms he has helped to secure.

If there is a problem with this book’s back-and-forth method—and there is—the cause lies less in the disorder of its plot than in the flip side of the author’s eschewal of tendentiousness: namely, his studied disinclination to invest his plot with meaning. A book anchored in some of the most consequential battles for Israel’s life declines to tell us how or why those battles mattered. The same diffidence characterizes Like Dreamers’ tracing of the dissolution of the state’s regnant socialist ideology and the institutions of Labor Zionism, which we see crumbling from below as incrementally, as seemingly spontaneously, as Meir Ariel is drawn into the synagogue. As the book ends, in 2004, the former paratroopers are divided by clashing views on the fate of united Jerusalem, now claimed by the PLO as the locus of its capital; here again, in relaying the men’s arguments, the author strives for neutrality.

But why return to Israel’s “mythic moment” of victory in 1967 if one is unprepared to articulate what that moment signified, and what it continues to signify? If there is one thing the ideological wars over Israel legitimacy have taught us, it is that neutrality, impartiality, and indeterminacy are fodder for whoever and whatever is working actively against the very right of the Jewish state to exist.

To pass from Yossi Klein Halevi to Ari Shavit and My Promised Land: The Triumph and Tragedy of Israel is like moving from the admittedly buffeting winds of freedom into a long-term care facility. Shavit sets out, as he says, “to tell the Israel story” through family sources, personal history, and interviews. He begins his guided tour with the arrival of Herbert Bentwich, his great-grandfather, on an exploratory visit to the land of Israel in 1897, the same year Theodor Herzl founded the Zionist movement in Basle. In then guiding us through the country’s geography and history, Shavit selects places where members of his family settled. Thus, Ein Harod, founded in the valley of Jezreel in 1921, is the book’s emblematic kibbutz, while the city of Rehovot, where Shavit spent part of his own youth, forms the background of otherwise disparate narratives about Israel’s citrus industry and its atomic project.

This recruitment of his family is not intended as family history, however. Shavit scarcely mentions, for example, Herbert Bentwich’s eldest son, Norman, a British Zionist activist and author of Israel Resurgent (1952) who was the more commanding historical figure of the two. From his family, as from the country, Shavit chooses only what he wishes to show.

Which is fair enough. But what does he wish to show?

“For as long as I can remember, I remember fear. Existential fear.” These sentences introduce us to the awakening consciousness, at the start of the Six-Day War, of the nine-year-old who in later passages will go on to experience the terrors of the Yom Kippur War, the Iraqi SCUD missiles falling on Israel’s civilian population in the first Gulf War, and the shooting, rock throwing, and suicide bombings of two Palestinian intifadas. In sum, according to Shavit, Israel’s victories, like Israel’s vitality, serve merely to camouflage “how exposed we are, how constantly intimidated.” Projecting his fear onto the national psyche, he foresees the day when the life of his “promised land” will “freeze like Pompeii’s” as Arab masses or mighty Islamic forces overcome its defenses.

By age nine, any child with a passable Jewish education will have learned that the scouts sent by Moses to report on the promised land of Canaan committed a lethal sin when they instilled panic in the Israelites with accounts of the giants they had allegedly encountered there. (“We looked like grasshoppers to ourselves, and so we must have looked to them.”) The forty years of wandering through a desert that could have been traversed in a matter of weeks were divine punishment for the cowering faithlessness of these former slaves and their spineless guides.

Shavit is either unaware of the relevant Jewish lore or indifferent to its message. To be sure, fear is a rational response in a minority population living among hostile neighbors—but that is precisely why Jewish leaders have so often invoked this biblical episode to warn against undermining public morale. In my mother’s arsenal of daily proverbs, the only non-Yiddish saying she regularly incorporated was Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s “We have nothing to fear but fear itself.”

Although it tells a story of impressive national achievement, everywhere in My Promised Land the techniques of literary foreshadowing are deployed to telegraph impending doom. In 1926, the violin virtuoso Jascha Heifetz performs for thousands in a makeshift theater at Ein Harod. Here is Shavit’s take on what can only have been a thrilling occasion:

I think of that great fire in the belly, a fire without which the valley could not have been cultivated, the land could not have been conquered, the state of the Jews could not have been founded. But I know the fire will blaze out of control. It will burn the valley’s Palestinians and it will consume itself, too. Its smoldering remains will eventually turn Ein Harod’s exclamation point into a question mark.

Several pages later, he comments on the spring of 1935, when the citrus harvest has enriched the villages surrounding Rehovot and “Jewish medicine” has brought progress to “desperate Palestinian communities.” Somehow, he writes, the “Zionists of Rehovot” have convinced themselves that, thanks to their altruism, “the clash between the two peoples is avoidable.” But this is delusion. “They cannot yet anticipate the imminent, inevitable tragedy.”

So acute is Shavit’s anxiety that even the prospect of urban development suffices to darken an upbeat report on the integration of European and Arab Jewish refugees:

In 1957 [the moshav] Bitzaron is still encircled by breathtaking fields of wildflowers: autumn crocuses, asphodels, bellflowers, and anemones. But they are about to disappear. A wave of development is replacing them with more and more housing estates populated by more and more new immigrants who are rapidly become new Israelis.

Israel’s triumph—its valor, its initiative, its natural beauty—is real only as a foil for Israel’s tragedy, which is where the real emphasis falls in Shavit’s deceptively balanced subtitle. There is no humor or lightness in his telling—this, in a country that in 2013 ranks 11th in the world on the happiness index. Even his exuberant report on the sex, drugs, and gay scene of contemporary Tel Aviv serves as prelude to a lament on the widening gulf between secure and exposed sectors of the country—a gulf judged by him to position Israel, in its seventh decade, as “much less of a solid nation-state than it was when it was ten years old” (and the wildflowers were disappearing from Bitzaron).

What is all this about? One can see why it might be hard to tell the story of European Jewry in the 1930s without a sense of foreboding, given what we know of its fate. But why would a successful Israeli in a successful (if threatened) Israel unspool a narrative thread of decline and disaster reaching back into the 1890s, weaving a shroud in which to wrap his country’s irrefutable triumphs?

One obvious answer lies in the ceaseless Arab war against Israel, which began long before the emergence of the state and came to play an expanding role in the domestic politics of Arab and Muslim countries, in the rabble-rousing of their religious leaders, in the ideology of their terrorists, and increasingly, in our own day, in the mental formation of leftists and internationalists everywhere. In this reading, the drumbeat of aggression that frightened Shavit as a child would appear to have kept him traumatized ever after.

Yet the obvious does not apply here. For, according to Shavit himself, his fears arise less from what Arab and Muslim leaders intend to do to Israel than from what Israel has done to them. The fear of attack with which the book opens yields immediately to its anxious echo—“For as long as I can remember, I remember occupation”—and the second anxiety supersedes the first. The obsessive foreshadowing is all about the wrongs that Jews have done or are about to do the Arabs, from the great-grandfather who fails to “see” their villages on his first journey through the land of Israel, to the kibbutzniks of Ein Harod who “burn the valley’s Palestinians,” to the 1948 war, and onward till today.

In his chronological march through Israel’s history, 1897, 1921, 1936, 1942, Shavit situates 1948, the year of Israel’s founding, not in Tel Aviv with David Ben Gurion reading the proclamation of independence under Herzl’s portrait, and not among the about-to-be savaged Jews of Jerusalem (in fact, not one of his chapters is situated in the capital, where Shavit has also lived part of his life), but in the battle over the Palestinian Arab town of Lydda (Lod), where he emblematically recasts the creation of the state of Israel as naqba, the “catastrophe” that is the founding myth of Arab Palestinians:

Lydda suspected nothing. Lydda did not imagine what was about to happen. For forty-four years it watched Zionism enter the valley: first the Atod factory, then the Kiryat Sefer school, then the olive forest, the artisan colony, the tiny workers’ village, the experimental farm, and the strange youth village headed by the eccentric German doctor who was so friendly to the people of Lydda and gave medical treatment to those in need…. The people of Lydda did not see that the Zionism that came into the valley to give hope to a nation of orphans had become a movement of cruel resolve, determined to take the land by force.

Like women who hold up bloody sheets to confirm a bride’s virginity, Shavit waves before his readers every bloody act committed by Jews in (what used to be known as) Israel’s war of independence. This chapter of the book was the one picked out to be featured, before the book’s publication, in the New Yorker, a venue in which Israel’s bloody sheets are regularly hoisted in place of its blue and white flag.

And what is “Lydda”? The researcher Alex Safian has taken the trouble to separate fact from propaganda in Shavit’s description of an alleged massacre in that town, second only to the more notorious alleged massacre in Deir Yasin. Starting with the Israelis’ cannon-bearing “giant armored vehicle”—actually, a recovered Jordanian light armored scout car the size of a Ford SUV—Safian deconstructs Shavit’s inflamed portrait to establish the following: the Arab inhabitants of Lydda first surrendered to Jewish soldiers and then, having retracted their surrender when it seemed that Jordanian forces had gained the upper hand, went about killing and mutilating Israeli fighters. This alone might be seen as cause enough for a “cruel” response at the height of a war launched by five invading armies against Jews who had been prevented by the British from preparing defenses and were relying on paramilitary forces of young volunteers. Once the town was secured, the Israelis let the Arabs leave, something both sides recognized would never have happened had victory gone the other way.

Nothing that happens to the Jews concerns them alone, so it is worth pausing here to consider what it means to substitute the Palestinian term naqba for Israel’s war of independence. In her recent one-volume Israel: A History, the historian Anita Shapira describes the special strains on the Jewish fighters of battles like Lydda’s that involved the highly trained Jordanian troops. As compared with Shapira’s meticulous account of what she rightly dubs an “Arab invasion,” Shavit’s Arabs and Muslims are deprived of agency, morality, and will. They are never seen to be plotting or planting, they never consider strategy or its consequences, they never indulge in moral reflection or compunction. “They suspect nothing,” “they cannot imagine what was about to happen,” and so forth. This combination of solipsism and unintended racism reduces Arabs to bit players in a drama of Jewish guilt.

Shavit’s precursors, who settled Israel, saw very well the Arabs and their villages; their failure lay in imagining people, like themselves, who had been living among and at the sufferance of others (in the Arabs’ case, mainly the Turks) and who would willingly have let others live among them. Some, indeed, did. But this is what Shavit cannot “see.” He will not apply to Arabs and Muslims the standards of decency he expects of the Jews, so he must decline to hold them responsible at all for their decisions, their politics, their behavior. In reporting on his meetings with Jewish religious figures or others of whom he disapproves, Shavit makes a point of telling us how he stands up to them in argument. Not so in his chapter “Up in the Galilee,” where his Arab friends assure him that Israel is doomed, and in response he merely reaffirms his love for them, asking, plaintively, “What will become of us, Mohammed?” No wonder they respond with contempt.

A further casualty of this book is journalism’s commitment to truth. Forecasts of doom are glaringly absent just where they are needed—and nowhere more so than in the section where Shavit describes how in the early 1990s he and his leftist political camp decided to bring “Peace, Now” by obscuring the declared intentions of Israel’s enemies.

In 1992, Israel elected a government headed by Yitzhak Rabin on a platform of no negotiations with Yasir Arafat’s terrorist organization, routed ten years earlier from Lebanon and now relocated to Tunisia. Subverting the democratic process, a few Israeli leftists, backed by an American millionaire, secretly plotted with Arafat to install him as head of a “Palestinian Authority” in return for nothing more than his word that he would keep the peace. Again with American help, they persuaded Rabin to accept this contract, very much against his better judgment. Israel thereby put the world’s leading terrorist in charge of protecting his prime target, and then proceeded to support and arm him.

Yossi Beilin, one of those who organized the meeting with Arafat in Norway, now admits they never considered the risks of PLO non-compliance. So when Shavit writes, “Peace was our religion,” he means, we acted idiotically through self-deception. In recounting this episode, he fails to look for where the dog lies buried (to adopt the Yiddish and Hebrew phrase). It does not help that, by now, Shavit recognizes the failure of the Oslo “peace accords” of 1993. In this respect, indeed, he early on distinguished himself from his colleagues at Ha’aretz. Nevertheless, he is still convinced that “[we] were right to try peace.” Instead of applying his professional acumen to investigating his and his friends’ part in the ensuing disaster, with its staggering loss of Israeli life, he limply seeks exculpation in his motives.

Shavit ends his book as he begins it, with an image of concentric Islamic, Arab, and Palestinian circles closing in on Israel. But danger is different from tragedy, and the healthy fear that hostility inspires is different from the sickly fear of imagining that one is guilty of causing that hostility. Shavit fails to distinguish the triumph of Israel from the tragedy of the Arab and Muslim war against it—a war that began before 1948 and that has always been indifferent to concessionary adjustments of Israel’s boundaries or policies. The only harm Israelis ever did to Arabs—and I emphasize only—was to impose on the Palestinians a terrorist leader whom Israelis would never have allowed to rule over themselves.

Yossi Klein Halevi immigrated to Israel as a Jew. So did Shavit’s ancestors. But one can’t help wondering whether Shavit feels himself less elevated by Judaism than condemned to it. Missing from his description of Israel’s “Hebrew identity,” as he calls it, is any evidence of the powerful sense of identity that has enabled Jews through the ages to withstand the aggression of others. Of the superabundance of contemporary Israel’s Jewish culture—the poetry and song, the popular revival of piyyut (liturgical poetry set to music), the theatrical productions, the ferment of academic and intellectual life, not to speak of Jewish religious life tout court—vanishingly little appears in his book. Missing, too, are the finds of the City of David and the Second Temple, or the attachment to native soil that makes amateur archeologists out of so many Israelis; the ruins of Masada make an appearance as a contrived means of boosting military recruits’ feelings of obligation and allegiance. Yet why else except through the unbroken connection of Jews with their homeland would Israelis today be speaking Hebrew in the first place?

Cut off from its Jewish rootedness, Shavit’s Israel finds its main justification in the suffering and supposedly nightmarish fears of its Jews. But suffering is not a Jewish virtue, only the sometimes necessary price to be paid for the privilege of living as a Jew. Moreover, in a face-off between competing fears and miseries, how can the prospering Jews of a “start-up nation” ever rival the perpetually deprived Palestinian Arabs? In his book, they don’t.

Doing justice to the story of modern Israel requires the moral confidence to distinguish between a civilization dedicated to building and one dedicated to destroying what others build. Is it really necessary to reaffirm that the Jewish state rests on a foundation of moral and political legitimacy stronger than that of any other modern nation, or that Jews maintained their indigenous rights to the land of Israel both when they resided in Zion and whenever and wherever they lived outside it? In modern times, and in modern terms, those rights were affirmed repeatedly, both in international law and through the gigantic efforts of Jews themselves, who purchased great tracts of the land, won back expanses of swamp and desert, built industries and cities, and repopulated the country in an unparalleled process of ingathering and resettlement of refugees.

Since war remains, alas, the universal means of securing land when a claim is challenged, the Jews of Israel have had to defend their land more often than any other contemporary people. In peace and in war, Jewish sovereignty has required and still requires of them greater qualities of mind and spirit than those that maintained their ancestors for centuries in other people’s lands. If it took tremendous courage to reclaim the Jewish homeland, at least equal courage is required to sustain and protect it among people who are currently less politically mature than they. One can only hope that, in that monumental task, Israelis will manifest in their written and spoken words the same moral confidence that as soldiers they have shown in battle—and that those writing specifically in English will remember that, whether they wish to acknowledge it or not, prominent among their present-day assailants are Western liberal elites.

_____________________

Ruth R. Wisse is professor of Yiddish and comparative literature at Harvard. Her books include Jews and Power (Schocken), The Modern Jewish Canon (Free Press), and, most recently, No Joke: Making Jewish Humor (Library of Jewish Ideas/Princeton).

More about: Foreign Policy, Israel, Jerusalem, Jewish State, Kibbutz movement, Six-Day War, Yeshiva, Zionism