Ruth R. Wisse

Ruth R. Wisse is professor emerita of Yiddish and comparative literatures at Harvard and a distinguished senior fellow at Tikvah. Her memoir Free as a Jew: a Personal Memoir of National Self-Liberation, chapters of which appeared in Mosaic in somewhat different form, is out from Wicked Son Press.

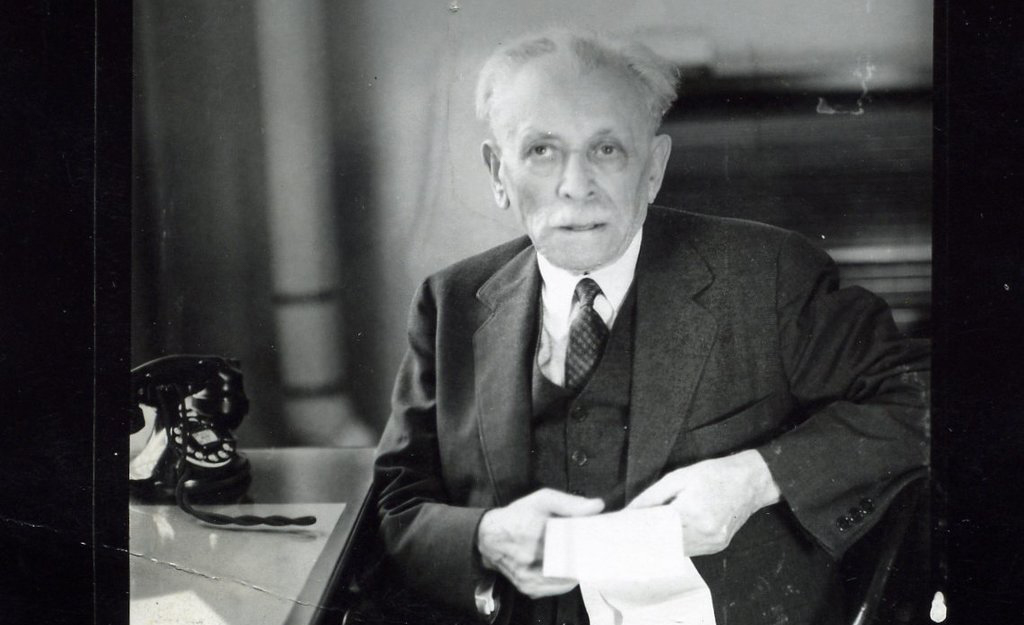

To Do Better in Our Time, We Must Learn What Abraham Cahan Accomplished in His

Yiddish socialist or proto-neoconservative?

The Very Model of a New York Intellectual

Abraham Cahan was one of America’s first great Jewish newspapermen, and set an example of independent thinking that the nation could sorely use today.

The Best Books of 2023, Part I

Featuring prime ministers, kidnappings, popes, silences, exiled shadows, portraits, intellectual origins, the best minds, and more.

The Logic of Jewish History

Lacking freedom, Jews once developed an ethic of martyrdom. Now, they don’t need martyrs, they need to stand and fight.

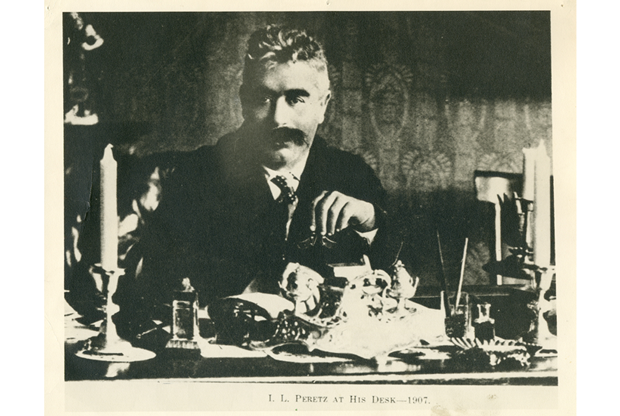

The Presence of Peretz: A Discussion with Ruth Wisse and Andrew Koss

The only Jewish personality who ranks with the Yiddish writer Y.L. Peretz was Herzl, who devoted himself to a similar task in the political domain.

I.L. Peretz and the Golden Chain

The great Yiddish writer envisioned an unbroken transmission of Jewishness through the generations, from biblical prophets to talmudic sages to literary giants like Heine—and himself.

The Biden Administration's Anti-Semitism Blindspot

Will the administration’s new strategy to counter anti-Semitism camouflage its own inaction?

The Sage and Scribe of Modern Israel

The novelist and rabbi Haim Sabato infuses tradition into fiction as well as any of the Yiddish greats. The difference? His work is unencumbered by modern angst.

The Asian American Challenge to Affirmative Action—and to American Jews

Why haven’t more American Jews joined the many Asian-American students and their parents protesting a policy reminiscent of the 1920s?

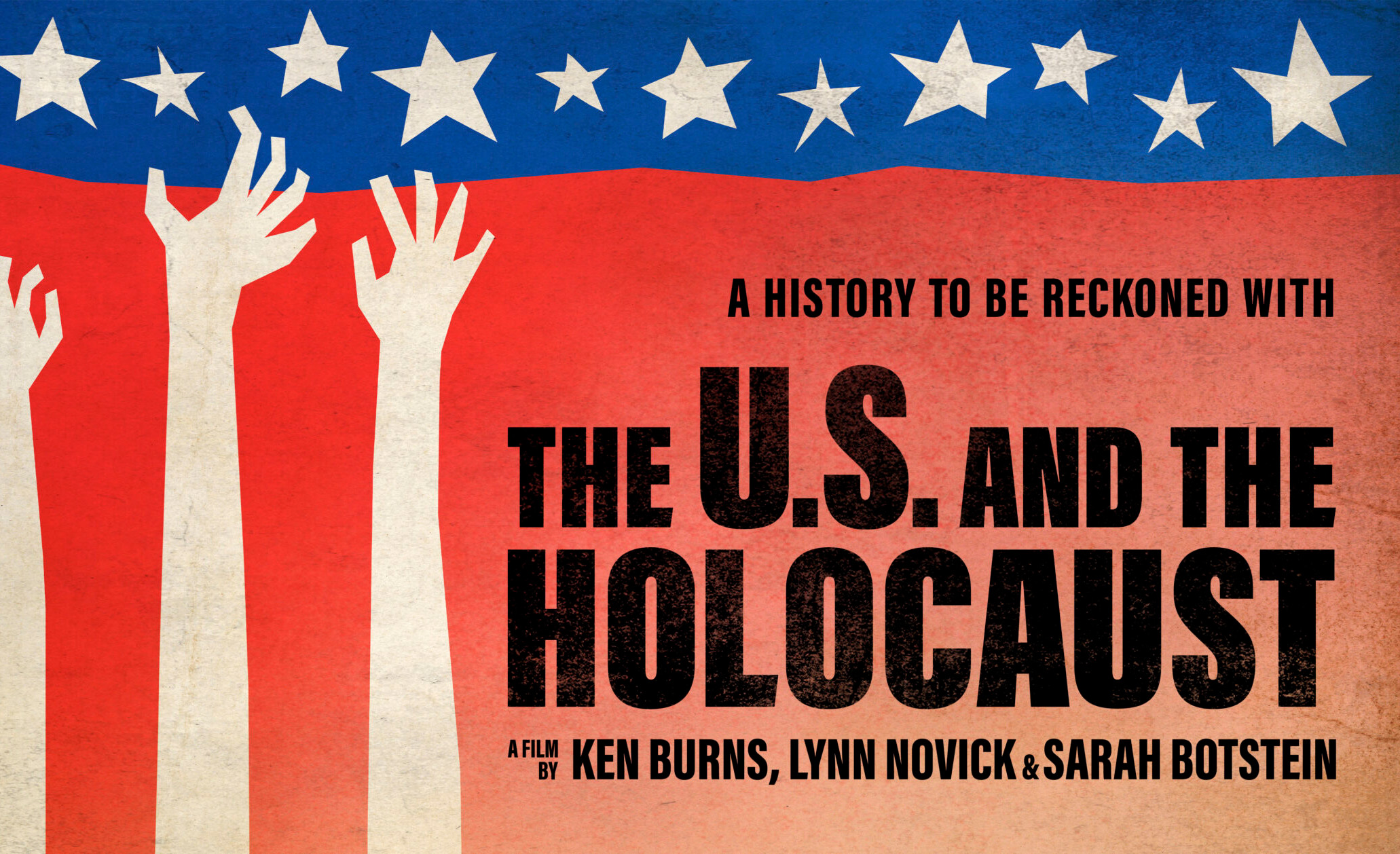

Why, Despite Good Intentions, Ken Burns’s "The U.S. and the Holocaust" Fails

Focusing on America’s failures to save more Jews in the Holocaust unintentionally strengthens the forces that would threaten Jews today. Here’s how.

What Can American Jews Do?

The direct target of anti-Jewish politics may be the Jews, but the more consequential damage is to the land of Lincoln. What can Jews do to help?

Is the Writing on the Wall for America's Jews?

Smiling at my visible distress, my neighbor said he was surprised: did I really not know what was going on to Jews around us? But it’s our responsibility to stay.

The Intensity of the Abortion Debate Is a Sign of America's Vitality

That America still so passionately debates abortion marks the difference between the stagnation of Europe and the hopeful civilization of the United States.

American Jewry's Stunted Sons

The middle of the 20th century inaugurated a time when American Jewish sons stopped being able to imagine themselves as Jewish fathers—and we’re still living in it.

Johanna Kaplan's Serious American Jewish Comedy

The characters in her new story collection are fully formed creatures of that transitional 20th-century moment between European Jewish survivors and American forgetters.

What the Children of American Jewish Communists Needed, and What They Owe

The children of Jewish Communists needed a therapeutic process to work through the effects of growing up in a political cult. They didn’t get it.

Watch Mosaic's Dramatic Reading of Isaac Babel’s “Red Cavalry”

Watch our recording of the classic Russian Jewish stories. Then stick around for the discussion with Natan Sharansky, Ruth Wisse, and Gary Saul Morson.

The Best Books of 2021, Chosen by Mosaic Authors (Part I)

Five of our writers pick several favorites each, featuring a duke’s children, Jewish treasures, zealots and emancipators, revolts, dual allegiances, spies, and more.

Canaries in the Coal Mine: Dara Horn and Bari Weiss

Jews can do their fellow citizens a favor by identifying the sources of cultural poison before the toxicity turns fatal. Hardly anybody is doing it better than these two.

“All the World Wants the Jews Dead: An Overwrought View from the Peak at the Bottom”

Before Dara Horn’s People Love Dead Jews, and before Bari Weiss’s “Everybody Hates the Jews,” there was Cynthia Ozick’s still powerful and urgent essay in Esquire.

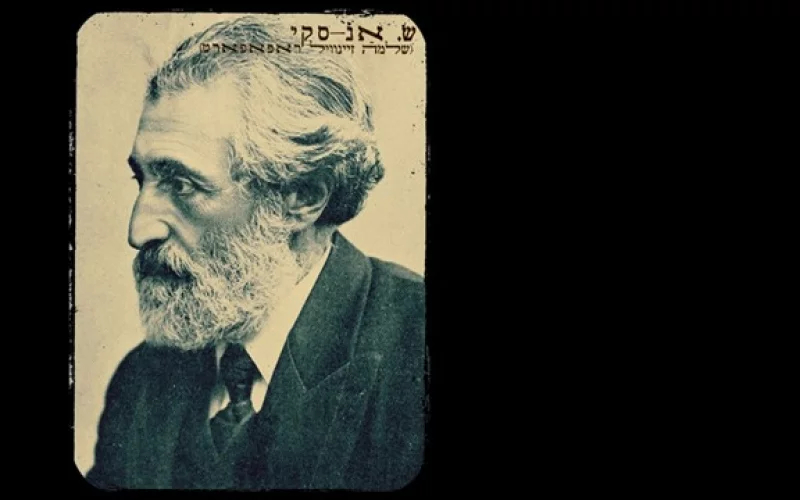

The Crackpot Ideas of Yiddish Fiction's Most Improbable Scenarios Become Real

S. Ansky’s radical yeshiva boys used to seem unreal. But observing today’s political scene has taught me to understand them.

A Threat Assessment for American Jewry, Part Two

Parts of the Jewish people stand up to the barrage of anti-Semitism, but others do not. Those others are part of the threat.

A Threat Assessment for American Jewry, Part One

Which of the recent samples of anti-Semitism—on the street, on campus, in Congress, or in the clergy—is the greatest threat to America and the Jews?

Two Favorite Poems, and How they Define Israel and America

“The New Colossus” by Emma Lazarus and “The Silver Platter” by Natan Alterman distill, reinforce, and hallow what makes each nation distinctive.

The Hounding of Noam Pianko

The latest drama in the field of Jewish studies has turned into a campaign to reframe the perpetuation of Jewishness as a dystopian project of enforced reproduction.

Two Views of Jews and Free Speech

Samuel Goldman and Ruth Wisse tackle Jewish attitudes toward free speech, social media, and the tendency of American Jews to support ideologies that harm the Jewish community.

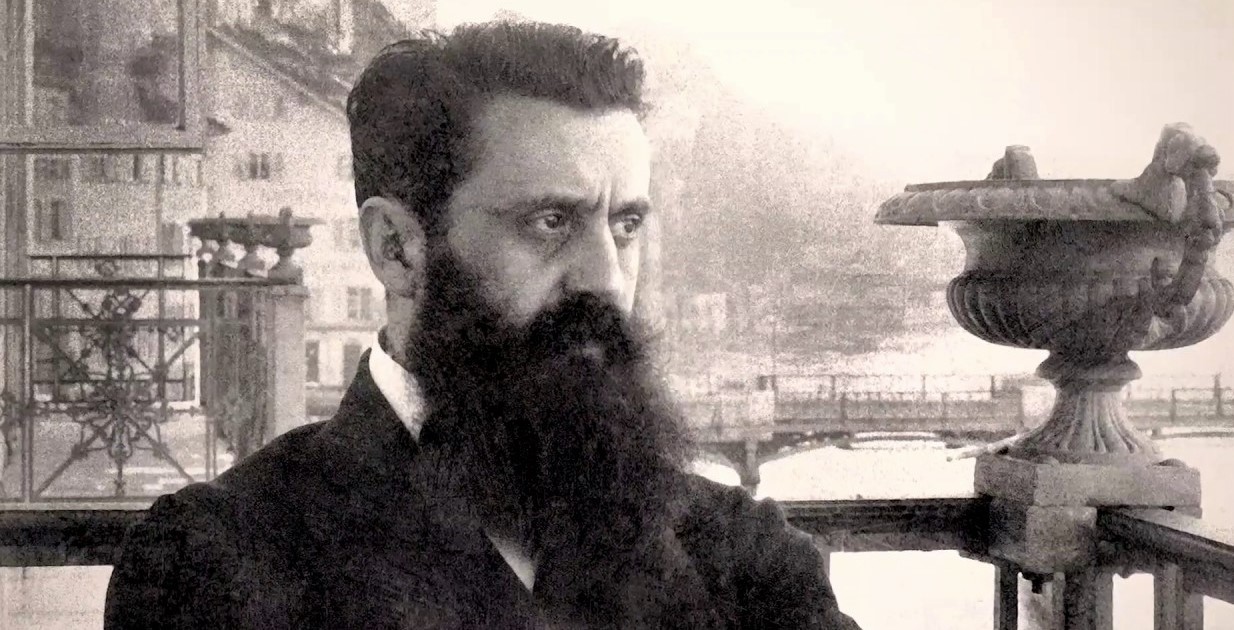

How Herzl's Wardrobe Galvanized the Jews

Back in my teens, when I began reading and thinking about Zionism, I thought the founder of the movement was a snob. I was dead wrong.

Chaim Grade’s Eternal Argument

The intimate, internal quarrel shows Jews doing what they have always done—but while they’re standing among people who have been dedicated to their murder.

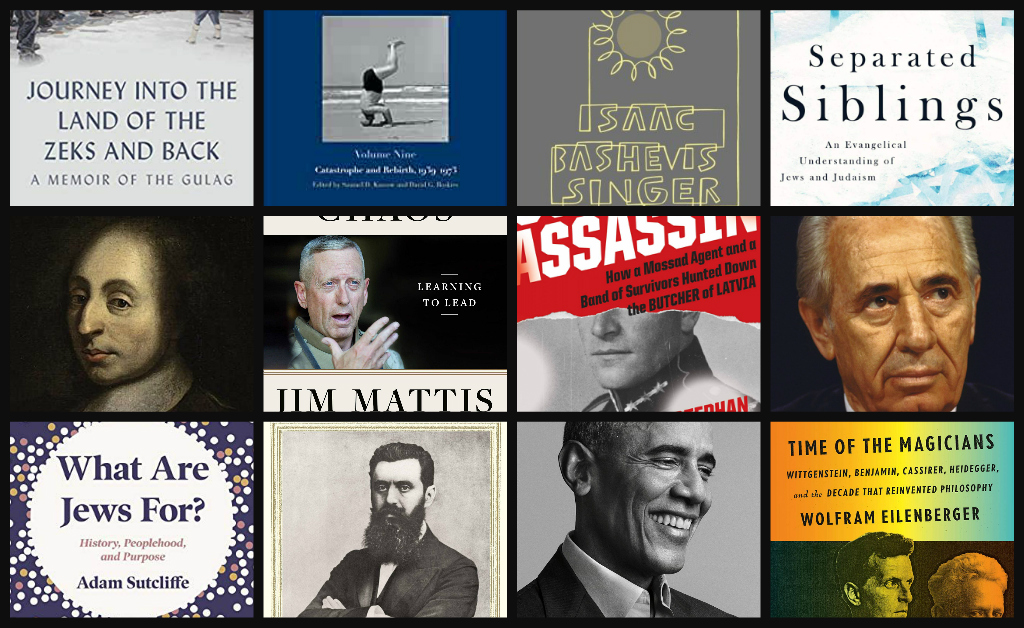

The Best Books of 2020, Chosen by Mosaic Authors (Part II)

Five more of our regular writers pick several favorites each, featuring what Jews are for, magicians, assassins, call signs, chaos, separated siblings, and more.

My Quarrel with "My Quarrel with Hersh Rasseyner"

How I came to translate one of the greatest stories in all of Yiddish literature, a work that I believe uniquely illuminates the debate at the very center of Jewish modernity.

Podcast: Ruth Wisse on the Five Books Every Jew Should Read in Lockdown

The master of Jewish letters on what to do if you’re sick of baking bread and reorganizing your closet.

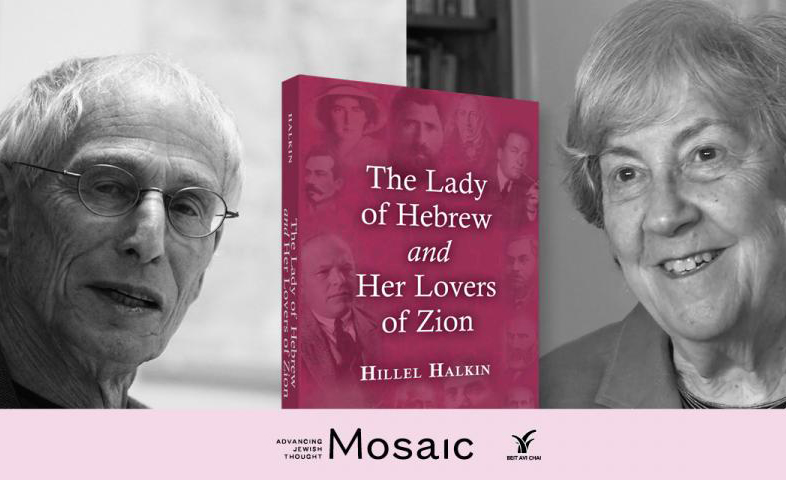

Podcast: Hillel Halkin and Ruth Wisse on His Life in Hebrew

The two giants of Jewish literature come together for a wide-ranging discussion centered around his new book on the seminal Hebrew writers of modernity.

A Tribute to Mosaic’s Founding Editor

Some of Mosaic’s regular writers reflect on Neal Kozodoy and his accomplishments.

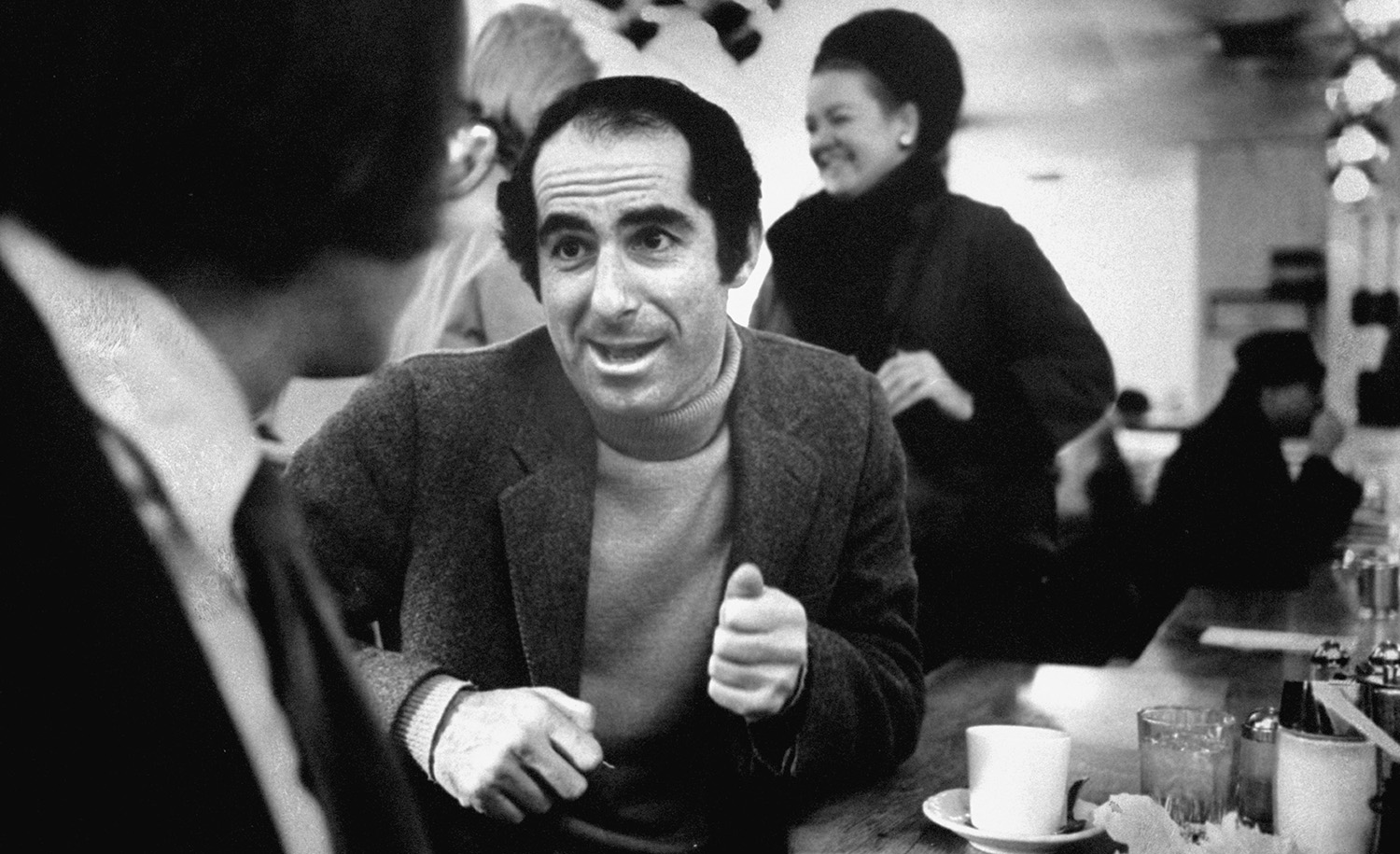

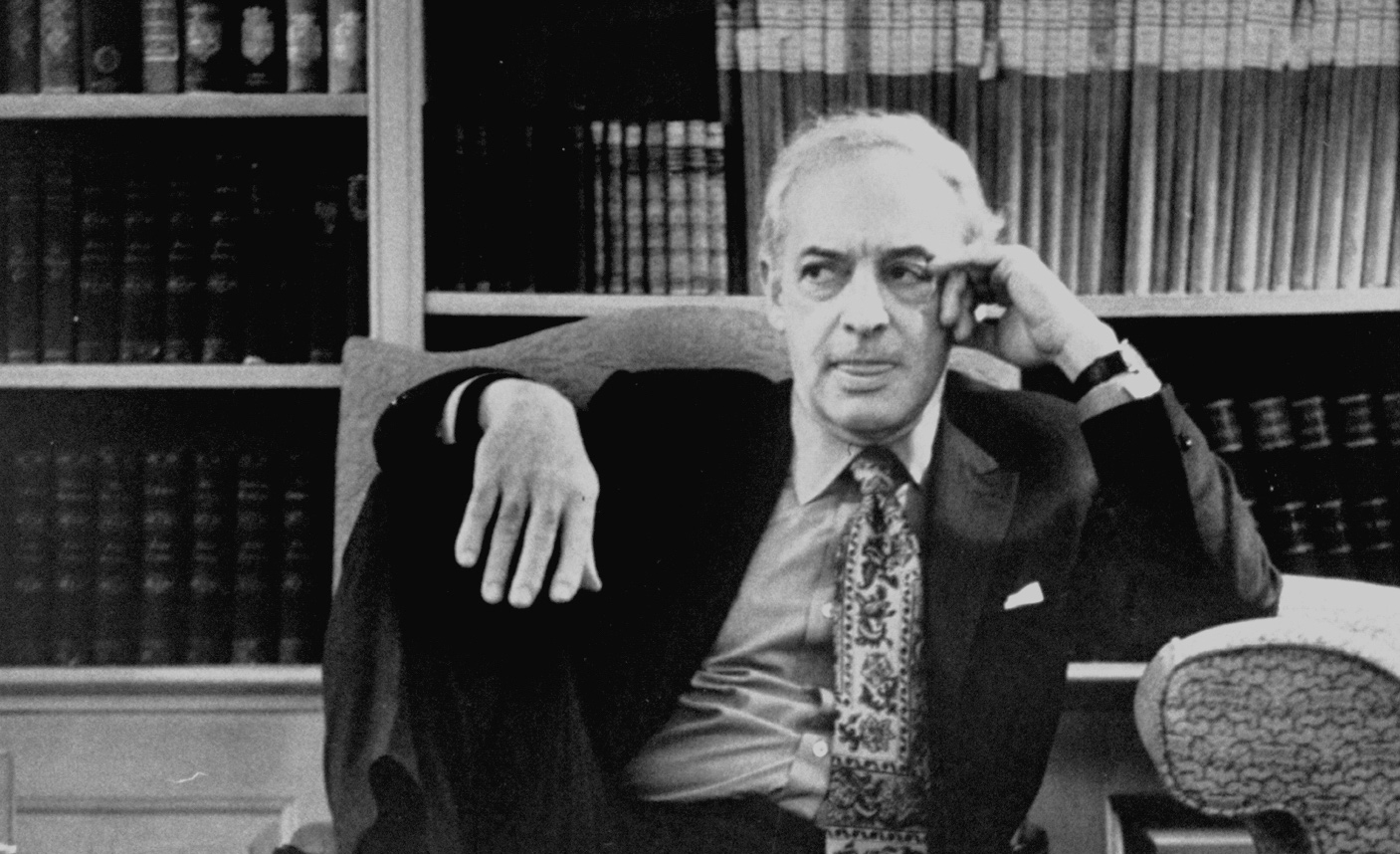

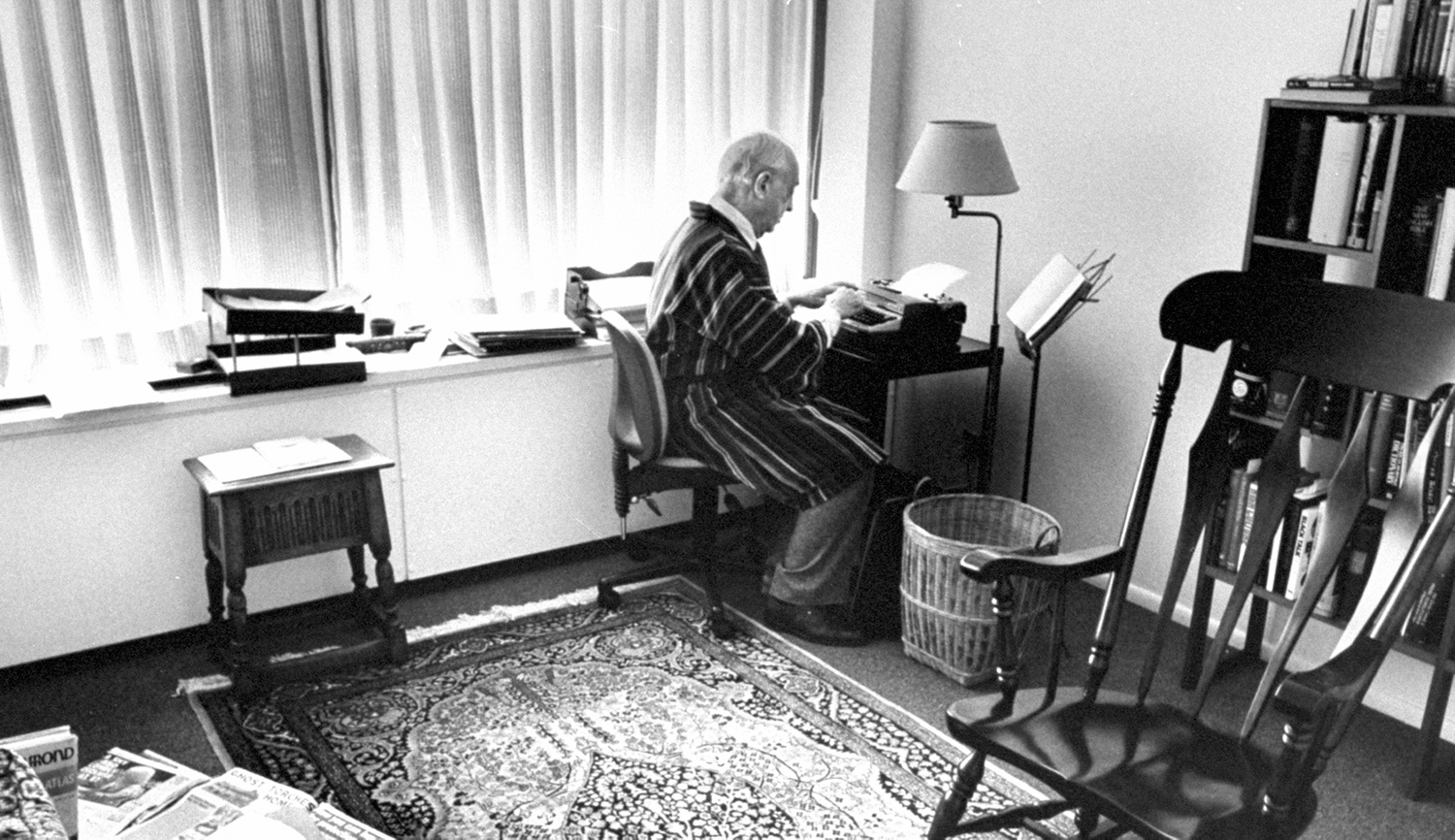

Podcast: Ruth Wisse on Saul Bellow the Thinker

Our resident scholar joins us to talk about her recent essay on the novelist Saul Bellow and to expand on her sense of him as a full-fledged Jewish intellectual.

The Best Books of 2019, Chosen by Mosaic Authors (Part II)

Six more Mosaic writers share their favorites, featuring shadow strikes, orchards, gleanings, constitutional evolutions and revolutions, serotonin, odd women, and more.

Bellow Was So Jewish He Could Travel Any Distance Without Risking That Allegiance

His reputation will fall and rise with his people’s.

What Saul Bellow Saw

The Jewish writer who became America’s most decorated novelist spent his early years prodding the nation’s soul. Then, sensing danger to it, he took up the role of guardian.

Reckoning; or, the Distressing Transformation of Harvard (and American Academia)

What I witnessed in my two decades of teaching at Harvard.

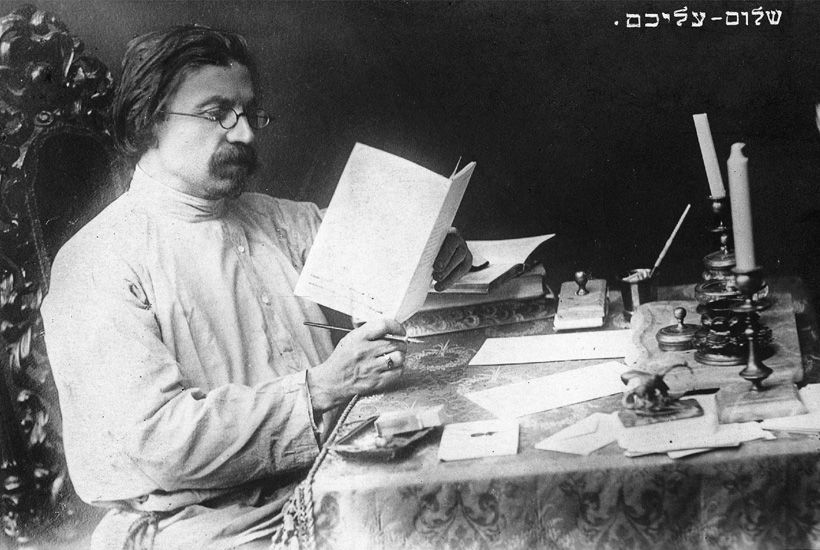

Podcast: Ruth Wisse on Tevye the Dairyman

The renowned expert on Yiddish literature stops by to talk everything Tevye, Fiddler, Sholem Aleichem, and more.

Why It's Necessary to Bring Jewish Communism into Full View

Airing the complicity of some American Jews with Soviet criminality is essential to the honor and the reputation of the Jewish people.

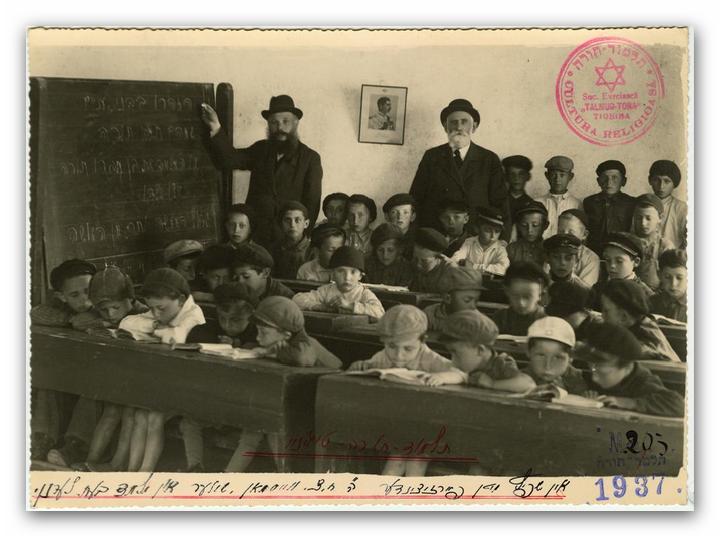

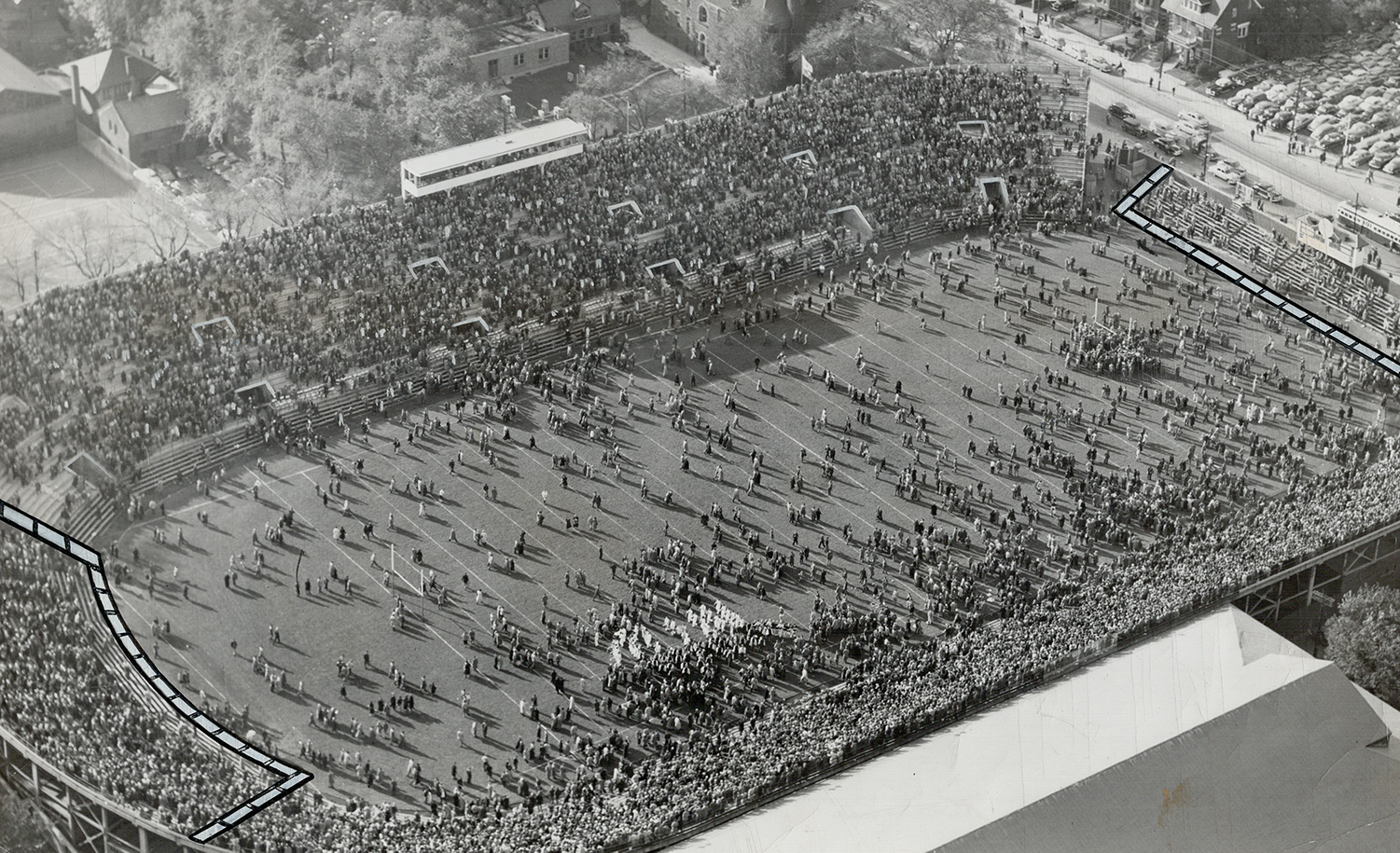

Arrival; or, Yiddish Makes Its Way to Harvard Yard

At arguably the moment of Harvard’s greatest involvement with Jews and Judaism, new movements in (anti-)intellectual thought started to creep in, too.

Leadership; or, Some Specific Strengths and General Failures of the American Jewish Fighting Spirit

From academia to philanthropy to journalism, my experience with Jewish leadership has been by turns discouraging and inspiring.

Contention; or, My Disputes with Irving Howe, Yiddish Academia, and Holocaust Memorials

Contention was so much a part of modern Yiddish culture that, in any study of that culture, it was all but taken for granted.

Politics; or, Grappling with Liberalism and Women's Lib

I expected the women’s movement to evaporate as quickly as it had materialized. It was the worst cultural prediction of my life.

Intellect; or, Daring to Become a Writer

On making one’s way into the “intimidatingly smart” realm of the New York Jewish intellectuals, and the company of I.B. Singer.

Ascent; Or, Moving to Israel in the 1970s

For me, living in Israel is a moral imperative. There is no elegant or painless way to describe why, after a year, we left.

The Best Books of 2018, Chosen by Mosaic Authors

Letters, antidotes, eternal lives, outcasts, secret worlds, pogroms, and more.

Perseverance; or, My Fight to Study, and to Teach, Yiddish Literature

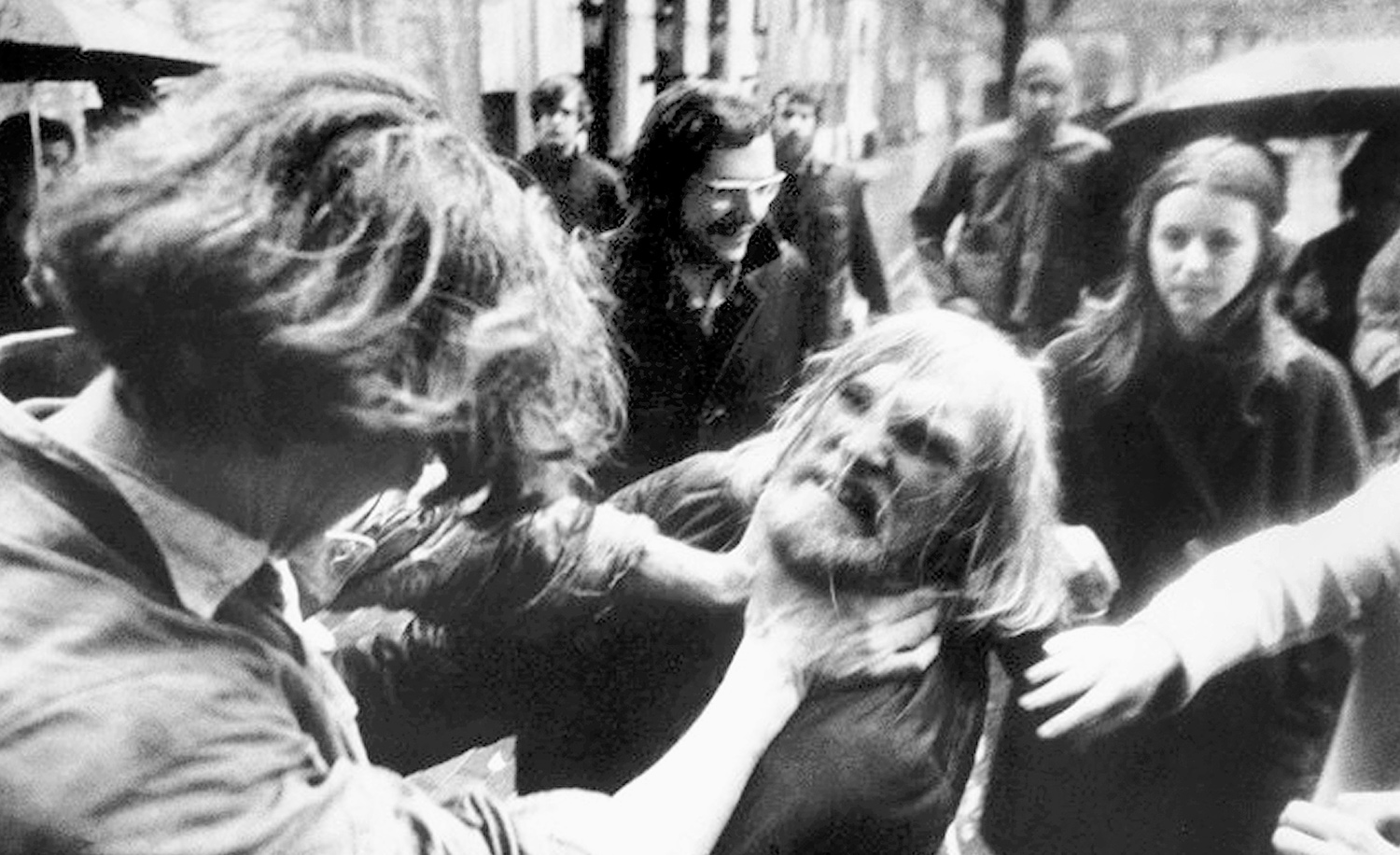

In the late 1960s, appointments in Jewish studies were springing up in tandem with the “adversarial culture.” But we intended to strengthen the universities, not to trash them.

Destiny; or, How I Found My Two “Basherts”

Ruth R. Wisse discovers her husband and her subject.

Discovery; or, the Ferment of Jewish Montreal in the Fifties

With the relaxation of Catholic influence in Quebec, local Jewish culture began to come of age and flourish.

Accommodation: Or, Growing Up Jewish in Protestant Canada

We were invited to join in the school’s prayers and hymns, but our grateful acquiescence also implied there was something illicit or shameful about our Jewishness.

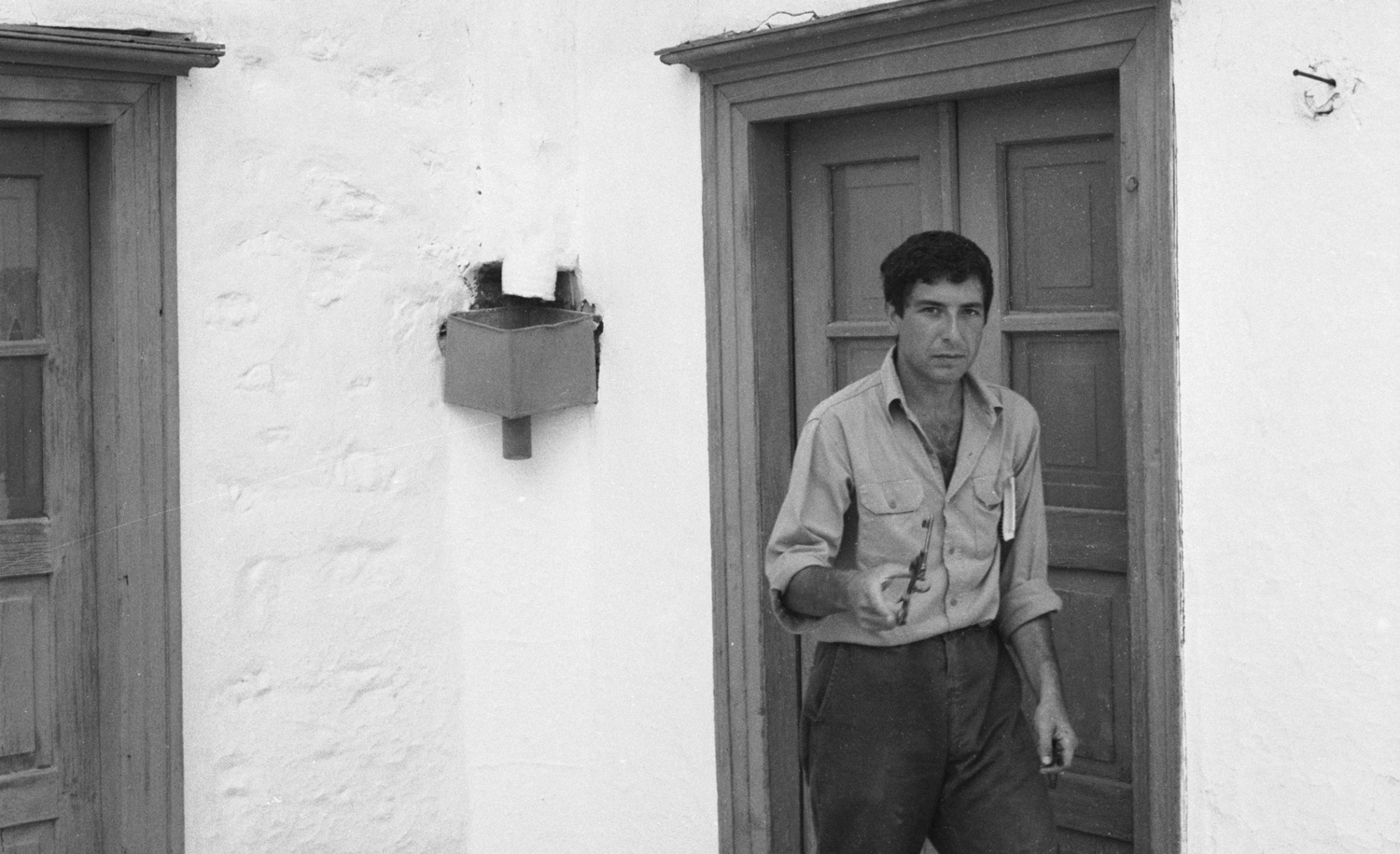

Responsibility; or, My Brother and I (and Leonard Cohen) Go to Summer Camp

And come to differing conclusions about the obligations of collective living.

Freedom; or, How a Family of Survivors Found Its Place in Jewish Montreal

Father brought us out of bondage, but Mother decided where we were to settle and how we were to live.

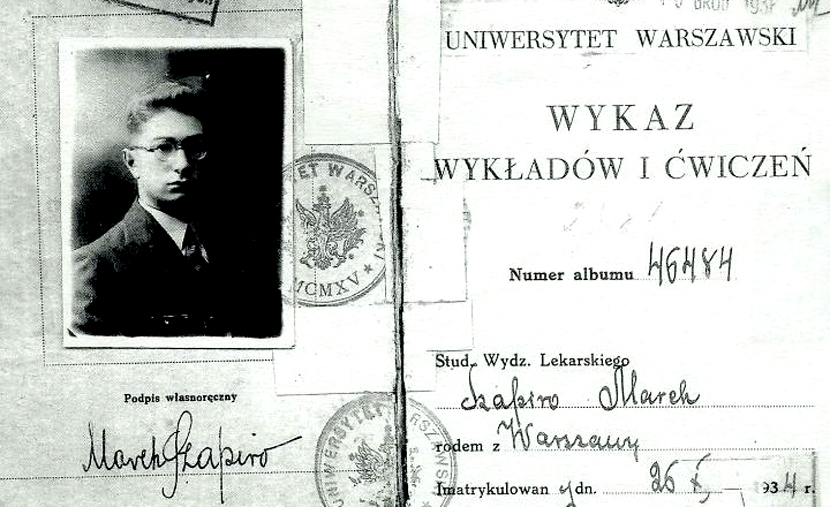

Survival; or, How My Family Beat the Odds in 1940

It wasn’t easy for an entire Jewish family to escape Eastern Europe in the mid-20th century. Ruth Wisse’s did.

Best Books of the Year, as Selected by Mosaic Authors

Spy games, catch-67s, lionesses, smugglers, patriots, setting suns, and more.

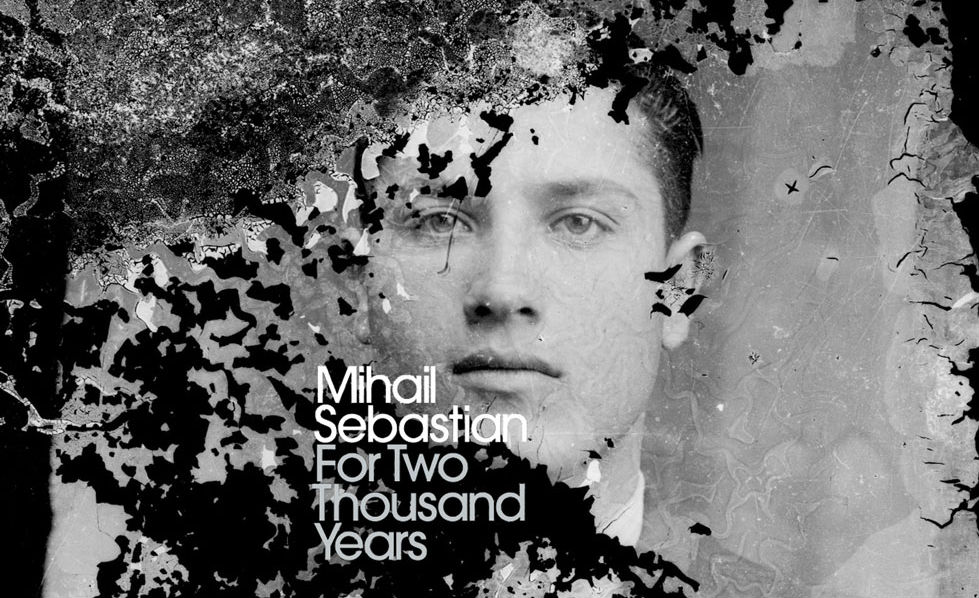

A Romanian Jew's Private Judgment of a World Bent on Condemning Him

In brilliantly charting the psychological effects of anti-Semitism on both its perpetrators and its victims, a newly translated 1934 novel outdoes even such master analysts as Freud and Proust.

My Life with Leonard Cohen

Friends, but never close, our paths intersected and then diverged, until this past September, when I connected with Leonard for the last time.

Jews and Other Poles

Poland offered Jews some of the best conditions they ever experienced in exile—until it didn’t. How are Poles dealing with that history today?

The Society That Abandons Its Jews Abandons Itself

American readers might consider the flight of French Jewry to be as foreign as foie gras. But there are warnings to be heeded even by them.

Oslo on My Mind

Memories of the day, twenty-two years ago, when the Oslo Accords were signed—and of the price Israel paid for that “terrible mistake.”

The Problem Starts at the Top

Responsibility for American universities’ failure to confront anti-Semitism rests with administrators and faculty.

Anti-Semitism Goes to School

Anti-Semitism on American college campuses is rising—and worsening. Where does it come from, and can it be stopped?

Of Dogs and Jews (and Lena Dunham Too)

A stale New Yorker quiz prompts stale accusations of anti-Semitism. More interesting is the trope of the canine Jew.

Isaac Bashevis Singer and His Women

What drove the great writer to employ a “harem” of translators? A new film tells much, but not all.

The Herd of Independent Minds

What does it mean to be “pro-Israel” on campus today? A new novel tells the tale.

What's Wrong with "Fiddler on the Roof"

Fifty years on, no work by or about Jews has won American hearts so thoroughly. So what’s my problem?

Their Tragic Land

Two acclaimed new books about Israel betray a disquieting lack of moral confidence in their subject and its story

By Our Efforts Combined

Dear Hillel: Don’t you think that Israel needs American Jews to help it withstand the campaigns of hate it faces?