Listen

Read

This transcript has been lightly edited for clarity.

Andrew Koss:

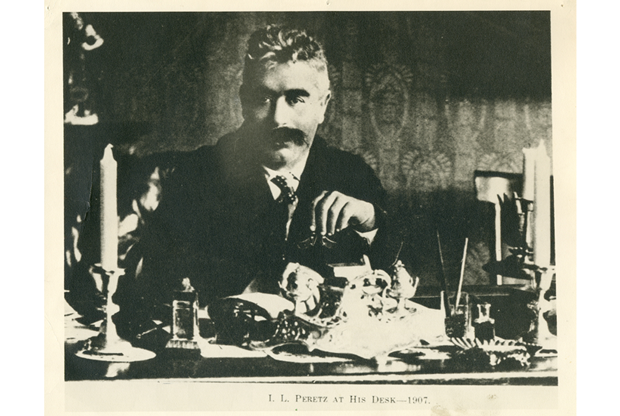

I’m Andrew Koss, the senior editor of Mosaic, and I’m here with Ruth R. Wisse, who has written Mosaic‘s August essay on the subject of the Yiddish writer Yud Lamed Peretz, as he’s known to Yiddish speakers—I.L Peretz, Isaac Leib Peretz. He lived from 1852 to 1915, and he is one of the great modern Jewish and Yiddish writers, and really of a kind of founding generation of Yiddish literature.

I won’t even try to summarize this absolutely brilliant and wonderful essay, which is called “I.L Peretz and the Golden Chain.” But it’s a brilliant and wonderful introduction to this writer for someone who knows nothing about him. And for someone who knows a lot about him, I would imagine you can still learn quite a lot and get a new perspective on what he means and what he means to us Jews in the 21st century. So I’d like to start by asking you, Ruth, a very simple question: how did you come to Peretz? Do you remember the first time that you read Peretz? And when did you kind of realize that you would be writing about him?

Ruth Wisse:

What a wonderful question. When were you born? Well, it’s not quite that early, but I began going to the wonderful Jewish People’s School in Montreal, Canada in 1941—I believe in 1941. And from that time on, of course, Peretz was part of our life because he had actually been one of the people to help found one of the first Yiddish day schools back in Warsaw in the beginning of the 20th century. And he was a very important part of the school curriculum.

So I cannot remember the first year when we were introduced to Peretz and Peretz’s stories, but they always seemed to be there. And let us say that in the amazing richness of Jewish day schools in Montreal, we were right at the center. The Jewish People’s School was a right-wing labor Zionist school, but right next to us was a left-wing labor Zionist school, which was called the Peretz School, the Yud Lamed Peretz School, and the two ultimately amalgamated.

So you see that the name Peretz and the presence of Peretz was almost always there for me—in the form of stories being read to us, in the form of stories that we studied. Basically my entire education in elementary school and through most of high school was very profoundly aware of the presence of Peretz.

Andrew Koss:

What has made you come to write about Peretz? Not just now, and not just giving the talk that this essay isn’t a version of, but that inspired this essay. And also many years ago, you edited an I.L. Peretz Reader. You’ve edited many very important collections, or at least several very important collections of Yiddish literature. I believe there’s only one that’s dedicated to just one author. I didn’t do a thorough bibliography, but there’s no Sholem Aleichem reader edited by Ruth Wisse. Is there a reason for this, and do you feel a particular affinity to Peretz?

Ruth Wisse:

I do, actually. I do. I very much appreciate the kind of mind that he had. What he was trying to do, at the turn of the previous century, was in fact to create a modern Jewish people that could make the seamless transition from a traditional life to a modern life, incorporating the best of each. And he felt that, of course, this was not an easy task on any level, but it certainly was not an easy task intellectually. How do you integrate these things or how do you meet the challenges basically, which is always what it was. And that is the task that he undertook.

I’m not sure that he ever said to himself, at any given point, I am going to be the leader of this new modern Jewish nation, or the thinker that sees us through to this new condition. But he became that person in the course of his life, and he played that role in Warsaw, in Jewish life in Poland for 25 years between 1890 and 1915. So I would say that the only person, the only writer, certainly, and I think the only Jewish personality who ranks with him in importance, is actually Herzl. And Herzl, of course, is the one whose vision ultimately triumphed, because Herzl devoted himself to a similar task in the political domain.

Peretz, very interestingly, lived in a completely different environment. He lived at the heart of Warsaw Jewry, which was at the heart of world Jewry at that time, in a huge Jewish community, and he had higher hopes for it. He saw the modern Jewish people really forging itself culturally. He saw us as a cultural people, basically the same way that people would say that we are more a religion than a nation. Well, he saw us as a nation, but he saw us as a nation based on its values, based on its literature, based on its cumulative culture. He saw us as a civilization, basically.

Peretz was definitely not an anti-Zionist ever, it’s just that he did not see that one could transport even the 300,000 Jews of Warsaw, let alone the millions of Jews in Eastern Europe, to Palestine. That did not seem to him at all like a practical answer to the transition of Jews to modernity. But he did see it as a possibility to forge a modern Jewish cultural nation, bringing everything of the past with it, but also now beginning to integrate everything that belonged to the present and that would belong to the future.

Andrew Koss:

That’s fascinating. I think I want to stick to this comparison between Herzl and Peretz. It’s easy to see— especially from our perspective in the 21st century, and especially to anyone who’s studied Jewish history, the way it’s taught in America, and I think in Israeli universities—the differences between Peretz and Herzl, which we tend to emphasize. But I want to look at the similarities. I think, most importantly, they’re both Jewish nationalists. Is that something you would agree with?

Ruth Wisse:

Absolutely. They both take their examples from European nations. Look, this was a time of emerging nationalisms across Europe. The great example was Italy for them. That had been the great example already for Moses Hess much earlier. And that is to say the consolidation of Italy seemed to people an example of how a modern nation could be formed. I can’t remember which of the writers about Peretz, when he died, called him the Jewish Garibaldi. In other words, he was the parallel to the nationalism of Italian unification.

Andrew Koss:

Yes. For those of you who are not up to date on their Italian history, Garibaldi is sort of both the Herzl and the David Ben-Gurion of Italian history who unifies these disparate states, some of which are ruled by non-Italian powers, and brings them together in the 1860s, I believe, into Italy as we know it today. It’s interesting also because nationalism is a word that’s come back and it gets thrown around a lot, perhaps misused, or at least it’s taken on a new meaning as a very particular political program. How would you define nationalism as Peretz understood it?

Ruth Wisse:

It’s not an easy question to answer because his thinking about this question changed quite a bit during his own lifetime. And by the way, he was worried about chauvinism. He was worried about it. I think the way in which he saw it was the way in which it presented itself to him. He thought that one might go beyond nation-states and that there would be a kind of multicultural Europe. The example that he had was right there in Poland. The Poles were a minority in Russia in the tsarist regime, and Poland was not independent in those years. Poland was under tsarist regime, part of it, and the Austro-Hungarian Empire looked as if it could be a merger of various ethnicities, and that there didn’t have to be a kind of an independent nation-state.

So when he started, I think that his idea was of the kind of minorities’ rights that treaties came to much later, at least in Poland. When Poland finally declared its independence in 1919, then Poland was supposed to have rights for all its minorities. And having been a minority, you would think that that would’ve been respected. Anyway, that was the kind of image that Peretz initially had.

Of course, things changed very quickly during those 25 years. And one of the things that happened is that as soon as Polish nationalism began to grow and experience itself more and more strongly, and the prospect of independence, that is to say full independence, came into sight, well, lo and behold, a xenophobic element entered into it. It was a very strong nationalist element that said, wait a minute, there are too many Jews.

And one of the people to whom he was very close in his thinking was a thinker, Świętochowski, who was a very known liberal, who then said, “You know, it’s like salt in water. There’s a certain amount of salt that can be dissolved in the water, but if you put too much salt in the water, it doesn’t dissolve. And the Jews now are too much salt in the water.” That kind of reversal was shocking. And I think that as a result of that, and many other things, Peretz’s thinking continually evolved.

Again, one of the things that makes him so interesting, not just to me, but to anyone, I would think, is the degree to which he kept integrating new ideas, rethinking things in relation to almost everything that he read and everything that happened.

Andrew Koss:

That’s so interesting. I was thinking about Świętochowski and Peretz myself as I was riding in the subway this morning and going through my notes. And the interesting thing is that Peretz is born in 1852, so when he’s eleven years old, in Poland in 1863, there’s this uprising, as you know, against Russian rule, which is completely crushed and the results are terrible for Poles. It leads to an attempt to crush Polish culture as well as any smidgen of political independence. This is to Poles what the Bar Kokhba revolt was to Jews in the land of Israel in 135 against the Romans.

And they say to themselves, in a weird parallel to Yohanan ben Zakkai [an important sage from that era], we’re not going to get political independence in the near future. And we get this movement called positivism, which is related to Western European positivism. Which is to say, we’re going to cultivate Polish culture. We’re going to make people feel that they’re really Polish, and not that they’re just Russian, which is something that’s happening. We’re going to fight against assimilation. That’s a very familiar Jewish word, but this is something they’re worried about too.

It’s also a liberal era. They’re influenced by John Stuart Mill and Western liberalism, and they’re very open to Jews. This is the dominant intellectual movement of Poland in the 1860s and the 1870s and into the 1880s.

If we think about it, these are the years that Peretz is a teenager. He’s coming of age in the 1860s and in the 1870s. He’s someone who sees such hopes get crushed for the Russian Jews. They’re all living in the Russian empire, but the Jews living in the Russian part of Russia—what’s now Ukraine and Belarus and Lithuania and the Russian Federation—for them, the moment is 1881 with the pogroms. But for somebody like Peretz who’s living in the Polish part of the empire, it happens later. And I think it’s this feeling of seeing people that you trusted—Świętochowski is the best example—turn against you. I mean, it’s hard to think of a parallel, but maybe we do have parallels today.

Ruth Wisse:

Well, we do have parallels today, but you’re very right to point out that there were no parallels then. Because in addition to what you so helpfully pointed out, that 1863 uprising was the high point of what was called Polish-Jewish brotherhood. Because Jews were very much involved on the side of the Poles, and there were even Jewish heroes of that war and that uprising. So the hopefulness of someone like Peretz about Polish Jewish integration, brotherhood, whatever it was, going forward, is what made him begin to write in Polish, something which has almost lost sight of completely. His early Polish poems were never published, and he then switched to Hebrew and then to Yiddish. But we should remember that he really did come of age in that sort of glowing liberal period of very high hopes for a kind of ethnic pluralism that seemed very probable. I mean, there was just something that he experienced in the city of Zamość.

Andrew Koss:

I guess the parallel today is to see people who are leaders of liberalism and who believe in pluralism and then turn against Israel with absolute ferocity, or show complete lack of empathy or worse to the persecution of Jews. So it’s not so unlike our circumstances now.

Ruth Wisse:

No, and you remind me, that you asked me what attracted me to Peretz. Well, I wrote a book called The Liberal Betrayal of the Jews. So, much of what I have absorbed since childhood really comes out in that book—as you see, the more we talk about Peretz, the more we will see all kinds of similarities.

Andrew Koss:

Since you brought up language, I want to turn to that, and then maybe we can come back to these sorts of bigger philosophical and political questions. When we talk about any kind of literary figure, language is the kind of first level. It’s the foundation of any sort of literary activity. So we have Peretz, who writes his first poems in Polish. Then, in 1877, if my notes are correct, he publishes his first collection of poetry in Hebrew. And even in 1897, he publishes Ha-Ugav (The Harp) which is another Hebrew collection.

He’s writing in Yiddish by this point, but he’s still ambivalent. And eventually, he turns all the way to Yiddish. I want to ask about what made him do that, but I also want to share an interesting little anecdote, which is significant to me.

The first time I met you, when I was a first-year graduate student—maybe I wanted to impress you a little bit—I told you about the latest thing that I was reading. I was excited to hear what you had to say. It was the first primary source that I was assigned in graduate school: the writings of Alef Litvak, who was a Bundist, which was somebody who wanted a unique Jewish form of socialism and who wanted the Yiddish language to be the basis of this. And Litvak talks about trying to recruit Peretz, the great writer, to his cause. And he is in awe of Peretz and he’s writing letters to Peretz, and he writes to Peretz in Yiddish, Peretz writes back in Hebrew. So he says, “Okay. He wants to write in Hebrew, I’ll write to him in Hebrew,” and Peretz writes back in Yiddish.

And I think that captures a lot about the difference between political Yiddishism and literary Yiddishism, which we don’t have to go into too much detail. But what I want to talk about first is why does Peretz decide ultimately that Yiddish is his language of expression?

Ruth Wisse:

Well, in this, he is not all that different from Mendele Mocher Sforim and Sholem Aleichem who together with him form this amazing triumvirate at the beginning of modern Yiddish literature. One can make too much of that, of course, but it’s astonishing that you have these three figures. And they all were, at least, trilingual. That is to say they all wrote in the language of the land as well, Mendele and Sholem Aleichem in Russian, and Peretz also in Polish. So there’s nothing unusual about that.

What you point out is extremely true. This is true from the beginning of his career as a writer until the very end. He was the one person in his milieu that was much more leftist than that of the other two. He stood very firmly against language politics. And there are people who really were very angry with him, of course, those who really saw Yiddish as the proletarian language.

So when the socialist movement began to really consolidate and the Jewish socialist Bund was founded in 1897, the same year as the Zionist organization, it wanted Yiddish to be declared as the language of the proletariat. And that would mean that Jews were socialists by implication, right? They spoke Yiddish, the socialist language, and so forth.

Peretz was very much against this. And this came to a head in 1908, at what was supposed to be the first Yiddish conference, the first international Yiddish conference in the city of Czernowitz which was a polyglot city, by the way.

Andrew Koss:

It’s also, if I’m not mistaken, the city of your birth. Is that right?

Ruth Wisse:

It is the city of my birth, yes. So, it’s always associated with Yiddish, interestingly. And the conference, of course, as an international conference was going to issue all kinds of resolutions, and one of the resolutions was that Yiddish was to be declared a national language. This was a great moment, right? Well, there were Bundists there who said they wanted Yiddish to be declared the national language. And so, there was a great floor fight, and Peretz is credited with having blocked it. Had he not been there as an authority—and this is in the minutes of some of the people who wrote about it—had he not been there as an authority, the conference could never have come together on the idea of two national languages, which is the way the conference finally came down.

Moreover, Peretz at that point insisted that one of the things that had to happen is that the Bible had to be translated into Yiddish, because if Yiddish was to be a national language of the Jewish people, then you had to bring into it everything of greatest importance. And of course, what would be of greater importance than the Tanakh. And one of the writers whom Peretz kind of influenced was of course undertaking that as a major life’s project already.

Andrew Koss:

It’s interesting to note, and I actually meant to look up this essay this morning and didn’t get a chance to, Hillel Halkin, another Mosaic contributor and friend of ours, gives Peretz a really hard time about this. He quotes this exact line, “And above all, we have to translate the Bible.” And really goes after him.

Ruth Wisse:

Well, he might’ve seen it from a completely different angle at that point, not realizing fully the degree to which Peretz was really fighting the holistic Jewish battle in that moment.

Andrew Koss:

So moving on from here, and this is such a rich subject and there’s so much more to say. I want to ask about Peretz’s use of language. It’s not something you can get from reading translation, which is exactly why we have to talk about it. I’m going to give you a hypothesis and you’ll maybe tell me why I’m right, but more likely tell me why I’m wrong.

If we look at this—I was going to call them a holy trinity, but triumvirate is probably a better word—of three great Yiddish writers, Peretz, Sholem Aleichem, who of course is very well known for writing the stories of Tevye—and you can listen to Ruth’s class on these stories—and Mendele Mocher Sforim. If we compare their uses of Yiddish, I would say that Sholem Aleichem and Mendele, first of all, their language is very talky. You don’t feel like you’re reading a book, you feel like you’re having a conversation. David Roskies, another Yiddish scholar who happens to be your brother, writes somewhere that you write in Hebrew and kind of talk in Yiddish, even if you’re writing. I’m mangling the quote, but it’s something like that.

You get the feeling that they’re showing off. They’re doing everything they can with this sort of wild and colorful language. I think Mendele in particular will use every register of Yiddish against every other—the Hebrew, the Slavic elements, and the kind of basic Germanic elements all going in every which way. Peretz seems the most restrained compared to these people. You’re shaking your head, which is good, because I want to hear why I’m wrong.

Ruth Wisse:

As a matter of fact, since you quoted my brother, one of his lovely insights on this question is that Peretz was to dialogue what Sholem Aleichem was to monologue. So that’s the way he sees it. Not that there was any difference in their use of the verbal form, that is to say the language as it is spoken. Because in Peretz too, I mean, he writes as he thinks, and it’s very lively. And in many of the stories you do have this dialogic element in it.

But it is very different. And I think one of the reasons is that Peretz was writing for a higher level of reader. I think that in the case of Mendele, he actually said at the beginning that the reason that he started to write in Yiddish was because he asked himself, “For whom do I toil? For whom am I working?” And he realized that he wanted to write for people, but the people could only read in Yiddish. So it’s as if he stooped to conquer, which is always the way I see him.

Sholem Aleichem just came to it, and he called Mendele the grandfather, because he knew the degree to which he was following in Mendele’s footsteps, but he also saw himself as writing for the people. And so, it had to be popular. That’s what they were thinking.

That’s not what Peretz was about. Peretz was writing for people like himself. As a matter of fact, it’s Isaac Bashevis Singer who said about Peretz that he has the richest Yiddish. He says, “Why does he have the richest Yiddish? Because it’s a Polish Yiddish, not a Russian Yiddish.” Which is very funny, because he was of course writing Polish Yiddish as well. And he has an extraordinarily rich Yiddish, Isaac Bashevis Singer does.

But in his case also, I think they wanted Yiddish literature to be as literary as they were. So, that’s one of the reasons that Peretz feels a little bit different, I think, is because he is at a higher level.

But if I may, I would tell you that when I started to work on Peretz and when I was trying to put together the first translations and thinking of putting together a Peretz reader, one of the works that I loved were his Impressions of a Journey Through the Tomaszow Region in 1890, which is one of his first works, a series of stories where he as a statistician goes through the Tomaszow region and they are interviewing people. He writes these portraits of all the kinds of people that he interviews, and those are literary portraits. They do not pretend to be a statistician’s work.

So in the introduction to that, he describes how he comes to a town and how the people there see him and how they react to him and how he answers them. So this is also in the form of dialogue. It’s unbelievably interesting how the women look at him and then how he sits with a man and how the man is skeptical about him. “Who are you? What are you coming in here for? What do you think you’re doing here?”

Peretz is then sitting with one of the men of the town. And this man proposes that they have something to eat, but everything that comes up, the man says, “Oh, God will take care of it. God will take care of it. God will take care of it.” And Peretz, wanting to play the devil’s advocate here says to him, “I don’t understand. That no sooner is a Jew finished with children and what he wears at the wedding, when it comes to the concerns of the people of Israel as a whole, the average Jew has such faith and trust that he thinks that he doesn’t have to bestir himself personally in the slightest.” So he’s asking him, “How come when it comes to your business, you’re out there, you’re working, but when I ask you to do something for the public good, you say, ‘God will take care of it. It’s in God’s hands’?”

So the man then answers, and I’ll read you this in Yiddish. What does it mean? Okay. I wrote every word out. I understood every word. I read it 100 times. I could not make head or tail of it. I simply couldn’t understand it. In other words, what is he actually saying?

So I went to my father. My father read it with the intonations that come with it and then it all became clear. And he says, “It’s simple. The people of Israel as a whole, that’s the Sovereign of the Universe’s concern. He bears His own in mind. If such a thing were imaginable, if forgetfulness were possible at the Throne of Glory, there are those who know how to remind Him. Besides, how long can Jewish suffering last? The Messiah must come, either when we’re all guilty or we’re all innocent. But that’s not how it is with affairs of individuals. Making a living is a different proposition.”

I mean, I hope that this can get across. You can’t give this to anyone today. I mean, I don’t know how many people at the time could have, it’s only the people to whom this was already so familiar that it would make sense. How many Hebrew expressions he uses, and elsewhere too, how many talmudic expressions he uses!

As a matter of fact, when asked about that, I think it’s Bashevis Singer who said, “You know, it didn’t matter to the people. They wanted to learn these things from Peretz. They felt that he was writing with confidence in how much they could understand, so even if the younger people could not grasp everything that he was saying, they felt flattered by that, and they aspired to reach it.”

You see, it’s not just that he was writing for an audience, but he was writing for an audience already with the idea of cultivating this audience, of raising them up to a higher level, never talking down, but always really at his level, or talking up.

Andrew Koss:

While we’re on this comparison, I wanted to ask a second question, which is about humor. Peretz certainly has a sense of humor. You can see it even in this passage you read. But it’s such an important device to Sholem Aleichem.

In fact, with Sholem Aleichem, it’s hard to see often, I think, the deep thoughts he has about the Jewish condition that you’ve explained elsewhere. It’s hard to see that, because you don’t realize that he’s deathly serious.

And also, his work can be very, very dark if you look underneath the humor. But at least on its surface, it’s humor, and he’s a brilliant humorist, among many other things.

Peretz seems to use humor less. Is that correct? And then, why?

Ruth Wisse:

Very interesting question that you’re putting. Well, they’re very different people, and I think that one could speak, in Sholem Aleichem’s case, if you’ll forgive the expression, about the ontology of irony in his work.

I think that he really had a very deep sense of Jewishness as existing on two levels. And the most obvious expression of that is the way you move from the Hebrew to the Yiddish, from the high to the low.

And I think that he felt that this is the way Jews exist, not on one level or the other, God forbid, but somewhere being able to maintain this constant ability to hold these two truths together, which is to say, “Thou hast chosen us from among the nations, and why did You have to pick on the Jews?”

In other words, knowing that you are a chosen people and realizing at the same time that there’s nothing in your contemporary life that reflects that, on a political level and on a daily level and so forth.

And that’s how Sholem Aleichem’s humor works. Peretz is so very different. The words which are used for him are sometimes like neo-Romantic, but he experiences life differently. He really believes or wants to believe or doesn’t believe, but he is not an ironist.

He raises the question that you ask. Why is it that there cannot be humor? Why can I not laugh? And he just simply says, “Because it’s just too serious.” That nations that have this easygoing life, well, humor is possible for them, but it is not possible for us, where everything is really so loaded.

And so you see how temperament here matters and personality matters. I think he would’ve reached more for tragedy, and in general, I think that that is what he would have aspired to.

One of the writers that had a great influence on him was Nietzsche. And the music that he loved was Wagner—the great operas. Polish literature particularly made the greatest impact, and the Polish literature was all these great Romantic novels, these huge historical novels, these great passions and so forth. Well, that is a very different kind of literature.

Andrew Koss:

But there are two buts here. One is that, I think of the Polish writers of his time, I think of someone like Henryk Sienkiewicz, who is the most likely to be known, a Nobel Prize winner, Quo Vadis, all that, who wrote historical epics.

Peretz was not a writer of epics. He wasn’t even a writer of novels. He did best with the short story and the play.

Ruth Wisse:

Yes. Yes. But that’s not to say that that’s what he aspired to because he was stuck with short forms. It was the way his mind worked. And by the way, it was also the way his life worked. He worked from morning til 3:00 for the Warsaw Jewish Council. He had kind of a bureaucratic job from morning to 3:00. At 3:00, it switched, and then he went home.

And he was not only the great writer, but he had an open house, as it were. There wasn’t an aspiring writer anywhere in the whole periphery of Poland and Russia who didn’t come to his door to present his first writings, to see whether I really am a great writer or not, whether I do have a literary future or not. He was a great literary figure, a great literary presence, and a writer.

It was all short forms because that’s what he had time for, but we know how he aspired to the great forms, and we know this from one great story alone, many works but one, and that is his story “Devotion Unto Death.” Well, it’s a very complicated story. And do you know that Ray Scheindlin, Professor Raymond Scheindlin made an opera of it?

Nobody told Raymond Scheindlin that Peretz had aspired to write operas, but this work just seemed to have that operatic quality. It’s a work I would highly recommend. It’s one of the stories, by the way, that I do talk about in this next series of The Stories Jews Tell.

You see that what he was looking for, “How can I personify the really Jewish ideals, the great ideals at the highest level? The Tannhauser legend, what would it look like in its Jewish equivalent? Who would the Jewish male hero be? Who would the Jewish female heroine be?”

And that’s what the story does. It creates the male hero, who is the real scholar. What does it mean to be the real Jewish scholar, as opposed to a false Jewish scholar? That’s worked out in the figure of the male hero.

And what is the ideal Jewish woman? What are her qualities of being? And there, it’s so interesting, he gives us an anti-Eve. Eve was the woman who gave Adam the apple and who corrupted him, as it were. Well, here, there’s a Garden of Eden scene at the end where the female heroine sacrifices herself completely for the man. How amazing is that?

Peretz wrote quite a number of works of this kind, where you see him sort of creating, as well as he can, the model of what Jewish life is, the aspirational aspect of Jewish culture.

Andrew Koss:

I think feminists won’t be happy with the biblical story or with Peretz’s version, but—

Ruth Wisse:

Well, no. Renunciation was a great theme anyway. This is a theme that I love in literature, but other people don’t. And I must say, it is not a theme that young people are very much attracted to. They don’t like renunciation very much. One of my granddaughters likes Casablanca but hates the ending of Casablanca. Why don’t the lovers prevail?

Andrew Koss:

I don’t think that’s a reflection on youth. I think that’s a reflection on our times. I imagine the youth of previous times might have felt differently.

Ruth Wisse:

Maybe.

Andrew Koss:

Think of The Sorrows of Young Werther, where Germans read this book by Goethe and killed themselves afterwards.

In any case, I want to go back to one thing, to your answer about my question about humor and irony, because again, Peretz is able to use these forms.

You conclude the essay with this discussion of “A Night in the Old Marketplace,” where there’s a character who’s the clown, the jester. And he reminds me of a Shakespearean jester more than anything else. Occasionally, he’s very funny, but it’s a very dark, dark humor.

With I think Jewish literature in particular, there’s always a but. The one literary influence that you mention in the essay in any depth is not one you mentioned just now, and that is Heinrich Heine, who is a 19th-century German writer. He is from a Jewish family. He converts to Christianity and is, I think, one of the greatest German poets ever. He’s never happy about his conversion, and he writes often on Jewish themes, even though that’s what he’s not best known for. And he is a very talented humorist and perhaps the greatest ironist ever. It’s ironic, for lack of a better word, that—

Ruth Wisse:

Well, I thank you for reminding me of that, because this is very interesting in Peretz’s own development. In his early work, the Heine influence is very strong, and you do see many ironic works, and you see many works of satire that he wrote.

As a matter of fact, we could talk about Peretz’s satire. It’s piercing, and it’s extremely important. Some of his works of satire I keep teaching, because they mean everything to me. They’re still as current and as relevant to Jewish weaknesses as they were then. There’s that.

But Peretz himself regretted the surfeit of influence that Heine had on him. He thinks that in his youth, Heine was too important to him. I think that you can see that in the 1890s, he gradually moves quite far away from that style of writing and that kind of writing.

By the late 1890s, which became the most popular part of his writing life, he begins to write neo-ḥasidic stories, neo-folk stories. And there, you see a whole different side of him emerging. These are based on ḥasidic motifs, which he works in his own way. These are not real folk tales, but these are folk tales which he re-works in his own way. But they are aspirationally romantic and elevating.

Here, I think something in him rebelled against, among other things, impulses in the socialist movement itself, because everything there worked towards: let’s equalize. Egalitarianism was the great thing. God forbid that there should be inequality in the world.

Okay. Well, from economic perspective, one could see that if Jews were living in great poverty, one could see that one of the thing one wanted was to reduce the disparity between some of the very wealthy and some of the very poor. You could see that impulse at work.

But the longer this lasted, and the more it became a movement, and the more it became intellectually embedded, Peretz then reacted strongly against it. And he said, “Now, wait a minute. But what about the greatness of the individual? But what about immensity of striving? But what about the Promethean element in the human drama?”

You see, he did not like this flattening aspect. He did not like this collectivization when it became reductionist. So part of that expresses itself in a literary turn to a different kind of subject and a treatment of even the same subjects that he had treated, but now from a completely different perspective.

Jewish life in Warsaw: Jews amde up one-third of the city, living many of them in dire poverty, and then by the end of his life—he died in the first years of the First World War—refugees flooding into the city. He saw these little, little Jews. He saw this culture of beggary everywhere. And in reaction to that, you see, he wanted so much that literature should be able to uplift in some way, remind us of the greatness.

Andrew Koss:

To give readers a sense of his neo-ḥasidic tales, I think probably the best known story ever written by Peretz is a story called “If Not Higher.” I believe in some synagogues they even read it as part of the High Holy Day liturgy.

It’s a beautiful, wonderful story. I also have to say, just to editorialize here, I think Peretz’s neo-ḥasidic tales are so much better in every possible way than Martin Buber’s. But since you’ve mentioned that, I want to bring you to this quotation that I think brings together some of these different ideas you’re talking about, both the neo-ḥasidic turn and what I think is a kind of gloominess.

There’s a gloominess in a lot of Peretz’s stories. How can there not be gloominess when he’s seeing what he’s seeing, when there’s the anti-Semitism, and even from the liberals? Like you said, he dies in this great Jewish disaster of the First World War, and things were bad enough already.

So, I’m going to quote your brother again. This is from one of my favorite books, Against the Apocalypse. I’m not trying to bait you into some sort of sibling rivalry, but I want to hear what you have to say about this, because I thought this was fascinating.

This paragraph is talking about the travel pictures, which you mentioned, and Peretz’s writing about the shtetl Jews and Jewish life. And then, and now I quote, “That Peretz then did a complete about-face and began to extol the virtues of traditional piety in his neo-ḥasidic tales and stories makes sense in light of the prior revolt,” meaning his prior criticism of some aspects of traditional life. “The myth of the shtetl could be revived only when the actual historical shtetl was presumed dead, and only if said revival were informed by ideas far into the shtetl itself.”

Ruth Wisse:

Well, one would have to go into the thinking around that particular conclusion, as it were, that particular formulation. Periodization is not the way to study every great writer, but I think that the question of periodization in the case of Peretz is very important, because he does move from one realm to another. And, yes, in his early works, he writes a story called “The Dead Town.” It’s about a Peretz figure who meets someone on the road and he says, “Where are you from?”, and the man says, I’m from the dead town,” and of course, Peretz then takes this literally and says, “What do you mean? Where is that?” and so the person starts to describe it, and what he’s describing is a real town where the economy is dead, where the culture is dead as he describes it, where every aspect of life that he touches on is dead. And so, as the story progresses, it becomes more fantastical. And then he says, “So, the corpses come out at night and they take over the town, and then the living people go back and they become the thing, and there’s no difference between them,” but then the more he talks about the town, the man says, “I know that town.” He recognizes it.

This is so interesting: when you say a dead town, it’s like a dead metaphor. But what Peretz is able to do is animate the dead metaphor. He takes a dead metaphor: “The town is dead.” “What’s it like?” We talk that way. We say, “Oh, there was no action. It was dead.” He takes something which is a metaphor, and he then takes it literally to show that that’s how awful it is, that the metaphors actually become the reality that you can’t tell the difference between the living and the dead. Okay, then does he romanticize it afterwards? Does he do that in the neo-ḥasidic tales? I don’t think so at all. I don’t think it’s a romanticization of Jewish life or religion, or even Jewish values.

He uses that material because that is Jewish. That’s what he’s got. No writer has everything. He couldn’t use Quo Vadis; he couldn’t use the Roman games. There are parts of history that he couldn’t use because Jews in that part of history are not heroic. There’s nothing noble in that part of it. So, what can you use that you can turn into a kind of nobility? And that’s what he sees in Ḥasidism: not Ḥasidism itself, but he sees because it was so aspirational, that he can use the aspirational aspects, the spiritualization of Ḥasidism. He can use that framework for the kinds of things that he is getting at.

Andrew Koss:

This suggests that we’re talking about people who in no way idealized Jewish life in Eastern Europe, yet who also saw it as something that was in danger.

Ruth Wisse:

If you’re speaking about Peretz, I would say absolutely not. He did feel that ultra-Orthodoxy, stifling Orthodoxy as he saw it, was more moribund indeed. For much of the time, I really think that he saw it as not just something that was dead itself but that it was choking the life out of Jewishness. But again, as time went on, everything flipped: the dangers of the old trapping you with its demands of ultra-conservatism, and then increasingly the worry from the other side that kept getting stronger. One of assimilation, which began to move very quickly. We don’t think of things like that: the number of conversions, thousands of people converting because Judaism ceased to mean anything to them. And that combined with anti-Semitism and with a repressive regime that made it all the more important to convert because there were things that you couldn’t get unless you converted.

So, those two pressures that were really opposite pressures, but the pressure from the second side, that is to say from the side that was trying to crush Judaism, became so much stronger that Peretz really fought for everything that was alive. There was no one who thought of creating so much. He created a choral society. He helped to create the Jewish day schools. He created so many newspapers. Every new possibility that opened up, every new medium that opened up, he was there to take advantage of it, to build it. He opened an orphanage when it was necessary to do that for the children. It was everything for the living Jewish people to help it, and help shape it, to help animate it. By the way, the interesting question that was once posed to me. Anita Shapira once asked, “I want to know, why wasn’t he a Zionist?” because she is the great historian Israel and of the Zionist movement, truly a great historian.

Well, it’s not a difficult question to answer: the reason he was not a Zionist was because as we were saying before, Polish Jewry was so alive to him. This was a time of massive immigration, the time of the greatest migration in Jewish history, this was a time when you had two-million people coming from the same territory to the United States of America, and going to Argentina, and going to other places, and going to Palestine. This was not Peretz. He was immovable. The place was to him there. It wasn’t a question of being against the movement to the land of Israel. He was supportive of the idea, but it just wasn’t his practical daily life. His daily life was committed to the improvement of, the saving of, the encouragement of life there. He couldn’t see it in political terms, so radical as to uproot a people.

Andrew Koss:

This brings the conversation full circle, which is that his answer to the question of what should the Jews do is really this idea of the golden chain of tradition. Sitting here on the desk in front of us is a copy of the journal known as Di Goldene Keyt (The Golden Chain), founded by a wonderful Yiddish poet named Avrom Sutzkever—who was born in the same shtetl as my grandmother. More importantly, Ruth is one of the great experts and expositors of Sutzkever, but the point I want to make is that Sutzkever published this journal in Tel Aviv. Am I correct?

Ruth Wisse:

Sure, yes.

Andrew Koss:

So, this is where the golden chain led. But I just want you to for a minute explain to our readers what that concept means for Peretz.

Ruth Wisse:

Well, Peretz was very interested in generational movement, and actually quite pessimistic about it. He has a story about four generations, four wills, and it’s in the form of four last wills and testaments. The first one is so full and rich, and the last one is a suicidal one. He shows you really the decline of generations. Then at the end of his life, he turns to the theater as a possibility, because for the first time the tsarist regime allowed the Yiddish theater, so of course he began to write plays. One of them was this play that became The Golden Chain, although it started very differently, and then he wrote it as this. It is an amazing play. I wish somebody would take hold of it and perform it. I think it could be done.

But it begins most dramatically with the first generation that he’s going to be dealing with. It’s called a ḥasidic family drama in four acts. The first act is the act in which Rav Shlomo, the ḥasidic rabbi of a large court, is there. It’s the end of the Sabbath, all the people have been there over Sabbath. They’re waiting for the end of Sabbath because they have to go home to open their stores, to get everything to go back to make food for the children, whatever it is. Reb Shlomo says, “No,” he is not bringing an end to the Sabbath. He is not going to make havdalah because if God is not going to bring the Messiah. He is going to make sure that this is the end. He is going to force an eternal Sabbath to stay. He’s going to force it.

He has this amazing speech, “I don’t want any more of these little Jews coming to ask me with their little petitions, with their little questions,” and then he says, “Singing and dancing, we go to greet him. We, Jews of grandeur and glory, Jews of Sabbath rejoicing, our souls aflame. The clouds sever at our coming. Heavens throw open their gates. Into the divine cloud, we swim to the throne of glory on the stone of unblemished marble we stand, not beggars, not petitioners, but proud and glorious Jews who say to him, we could wait no longer, chanting the Song of Songs, singing and dancing, we come.”

The play goes on from there with the next generations that come after. I will not spoil it for anyone here. When Peretz was buried, he was given the largest funeral I think that had ever been seen in Warsaw, but it took ten years before they put up a monument for him. And that monument remarkably still stands in the Warsaw Cemetery, and those words are the words that they chose to inscribe on the monument to Peretz.

I don’t know if Jewish life has a more astonishing element in it. There in the Warsaw Cemetery now, you have that monument. That’s really basically all that’s left of the living Jews of Poland and of Warsaw, which were 338,000 the year that he died.

Andrew Koss:

Wow.

Ruth Wisse:

Right. So we’re there with this, but it stands with these words, “We could wait no longer, so we go chanting to you.” This is Peretz towards the end of his life, and you can see how he is fighting, resisting this idea that we are a small people, and that we are a victimized people, and that we are a people that has to react to history. No, he wants a hero that will impose himself.

Andrew Koss:

It’s a Zionist statement. If a Zionist writer wrote this, we would say, “This is just classic Zionism. We’re not going to sit around waiting for the Messiah. We’re not going to be little Jews anymore. We’re going to force the return of the Jews to the land of Israel. We’re going to force the end of the goles, of the exile, and we’re going to return to history.”

Last question before we end, the real last question, I promise: if somebody wants to start reading some Peretz, where should they begin? Can you recommend one or two stories to start?

Ruth Wisse:

Well, I hesitate to answer the question because that is the reason that I put together this last series of Stories Jews Tell, which is devoted to five Peretz stories, or five works by Peretz because they’re not all stories, and then five stories written by people in his circle. He had tremendous influence on younger people, but interestingly enough, the best influence you want to have, not one of them went in his direction.

Anyway, I think it’s just too large a question, and that’s why I put out an I.L. Peretz reader, which is still available I think, and it’s available on audiobook. So, I think that maybe enough has been said so people can decide whether they want the realistic Peretz, whether they want the Peretz of the critical period of his life, or whether they want the more neo-ḥasidic or neo-folk artist. There’s everything there.

Andrew Koss:

So go here sign up for Ruth’s forthcoming podcast series, Stories Jews Tell, which we will give you five stories about Peretz—

Ruth Wisse:

Five works by Peretz and then five others. The texts will be there for people so they’ll be able to read what will be talked about.

The Stories Jews Tell and Ruth Wisse’s writing in Mosaic is made possible by the generosity of Robert L. Friedman.

More about: Arts & Culture, I.L. Peretz, Yiddish literature