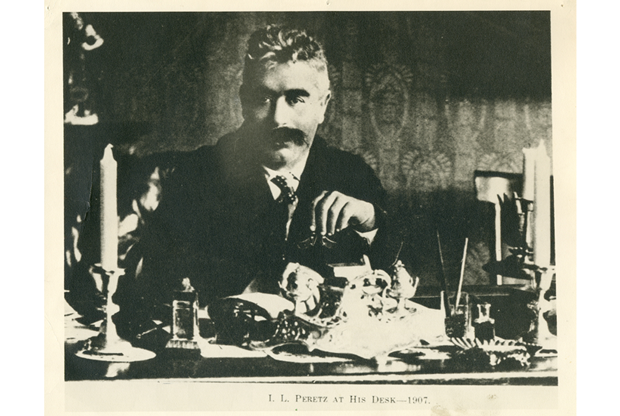

In September of 2015 I attended an international conference in Poland devoted to the centenary of the death Yitzḥak Leybush Peretz (1852–1915), the most influential Jewish writer of his time. The four sponsoring organizations, each with a strong stake in ensuring the country’s democratic future, were the POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews, the Polish Association for Yiddish Studies, the Foundation for the Preservation of Jewish Heritage in Poland, and the International Research Center on East European Jewry of the Catholic University in Lublin. Poland’s treatment of its sizable Jewish population had always been a gauge of its liberality, and Peretz represented that ideal: he had written some of his first poems in Polish and had briefly practiced law in his native region at a time when the emergence of a Polish-Jewish symbiosis seemed as possible as the fused identity of the American Jew.

Part of the conference was held in Zamość, Peretz’s birthplace, in the refurbished main synagogue on what is now Peretz Street, ulica Pereca, just off the city square—the rynek, or marketplace, that figures prominently in Peretz’s memoirs and literary works. The mayor extended us his personal welcome, paying our return bus travel from Warsaw. Several of the young Polish scholar-participants introduced fresh material on the author from their research in Polish sources and the Polish press. All this was heartening, yet most conspicuous was the absence of a single local Jew in a city where Jews had constituted about half the population between 1800 and 1939. It was in that synagogue, haunted by that knowledge, that I presented my paper on “The pursuit of justice in Peretz’s work.”

While no great writer can be represented by a single theme or subject, literature was for Peretz the extension of Torah for a modern Jewish people. Steeped in talmudic learning, he was fifteen years old when he entered “their House of Study,” as he referred to such marvels as the Napoleonic Code and European literature—the discovery of which forced him to straddle contrasting systems of theory and practice. What was the relation between sin and crime, between legal codes and their implementation? Did psychology’s new insights into human motivation affect the calibration of innocence and guilt? How could a minority like Jews or Poles under Russian rule attain political rights and what did they owe to one another in their parallel struggles? How did justice for women figure into human rights? Peretz assumed responsibility for fellow Jews who were quitting the yeshivas while keeping their prophetic-rabbinic tradition alive. If he could not represent them politically, he tried to be their voice and their guide through the story, poem, drama, and essay.

Peretz left us what all writers leave, a body of writing that we now read independently of the author and his circumstances. But the conference in Poland recalled that he was “more than a writer.” A people without central political authority that was in the process of recovering its sovereignty was in special need of leaders to chart the direction of its national independence. Theodor Herzl, a contemporary of Peretz who was also more than a writer, was persuaded by his experience in Western Europe to get the Jews out of the continent and back to their homeland, knowing that there was no liberal possibility for their integration into Germany, Austria, or France. Peretz was raised and embedded in the largest and most dynamic Jewish community in the world—the Jews who had lived and intermittently thrived in Poland from its beginnings. Unlike Herzl, he could not wish for Jewish life elsewhere and he could certainly not envision a Poland without Jews.

I. The Moral Universe of His Childhood

When Peretz began serializing his memoirs in 1911, he compared himself to the pious Jew who cleanses himself of sin in the ritual bath before he prays. The writer, he says, does the same thing, metaphorically, before he begins to practice his craft—except for those moderns who parade their sinfulness, “or steal sins from others if they don’t have as many as the market demands.” Though he was unquestionably modern, he presents himself as the fortunate product of an ideal Jewish upbringing, who remains within that culture of moral restraint.

His mother: when he was three years old, at the ceremony marking his start in ḥeder, he was asked to spell Vayikra, Leviticus, the name of the biblical book with which his studies were to begin. Not understanding exactly, he began to spell out the opening chapter, letter by letter. His mother, Rivele, bashfully moved off to a corner of the room so as not to show her pride. Later in the term, when his first ḥeder teacher was about to punish him for some mischief—apparently genius did not preclude misbehavior—the teacher’s wife intervened, saying, “How can you hit Rivele’s Leybush!? She deprives herself and her family in order to give charity to the poor!”

His mother’s reputation as a tsadekes, a woman of saintly virtue, was epitomized in the anecdote about Ayzikl, their water carrier, who was paid by the week for delivering water from the city well to their kitchen. When a guest poured full cups of water over his hands for the ritual blessing, his mother said, “frum oyf Ayzikl’s kheshbn,” pious at Ayzikl’s expense. Years later, in a much-developed version of his mother’s precept, Peretz wrote the story “Mendl Braine’s” about a husband whose reputation for pious good deeds comes at the expense of his overburdened wife.

His father was an equally formative figure. When the ruling tsarist government threatened to conscript local Jews for military service, he urged them to resist. They were afraid they would be arrested and thrown into prison but he assured them, “Only if they turn the whole world into a prison.” Peretz later harnessed this trust in collective resolve to the emerging Jewish socialist and nationalist movements.

His grandfather was remembered as the man who returned to town one Friday after having been forced into bankruptcy. He kept the Sabbath as always, but after Havdalah, he instructed his wife to lay out all their possessions, including her jewelry, and asked his local creditors to come and take whatever they felt they were owed. The creditors demurred, and grandfather eventually paid off every zloty. Those who strictly kept the Sabbath were no less morally exacting in their business transactions.

Peretz tells us that he used his great-aunt “without embellishment” for his much-anthologized portrayal of the rebbetzin of Skul in his Impressions of a Journey through the Tomaszow Region in 1890. This series of pen-portraits was based on a statistical survey of Jewish participation in the workforce and military that Peretz and his fellow writer Nahum Sokolow (later president of the World Zionist Organization) had been hired to conduct in the hope of proving to a hostile government that the Jews were productive, reliable citizens. Peretz drew on the experience for this literary work.

The widow of the rabbi of Skul is unwilling to live off the off the reputation of her late husband or the bounty of her children, and supports herself through a home potash- or soap-making enterprise. She explains that making potash requires no supplies or equipment. “You take ash from the fireplace, mix it with potatoes and other vegetables, stir it, boil it, let the liquid evaporate, and you get unrefined potash. Repeat the process, and you get the refined product.” She worries lest the authorities learn about her “business” and require that she take out a license, which would erase her small profit.

Peretz let us know that his business of journalism allows mixing personal experience with reportage. He is certain that his display of the rebbetzin’s independence, ingenuity, and innocence would more accurately convey Jewish “reality” than the statistics he and Sokolow had gathered, and that using his relative to flesh out this portrait was hardly dishonest, because there was more than one such widow in the Tomaszow region.

Thus, while many memoirs begin with hardships overcome—orphancy, dislocation, disability, war, or other cruelties—Peretz situates himself in a moral aristocracy. He does not accept the notion of innate goodness that was developed by Rousseau in his book Emile—“Everything is good as it leaves the hands of the Author of things; everything degenerates in the hands of man”—and instead he credits the Jews of Poland with having perfected over many centuries the way of life that God entrusted to them at Sinai. The Jews of his childhood, Jewish Zamość of the mid-19th century, form his image of a Jewish golden age.

II. Passage from Home

Why then, did Peretz not continue in the way of life he so admired? What happened to the golden boy of that golden age?

An explanation of sorts comes in his first published Yiddish work, the semi-comic ballad “Monish” (1888) whose hero he claims to have modeled on Leybush—himself. Monish is the child that every Jewish family wished for itself, so perfect that he is rumored to be the harbinger of the Messiah.

He soaks up Torah like a sponge./ His mind is lightning;

it can plunge/ from the highest/ to the most profound.

But since Satan is always on the lookout for the redeemer who would put him out of business, a devilkin brings news of this danger to Mount Ararat where Satan and Lilith reign. Modern Satan attacks his prey not through punishments as in the book of Job, but with European enticements. A German merchant arrives in town with his daughter Maria, who seduces Monish with her German song—recalling that Peretz was attracted by music, and by the opera of Wagner in particular. At first, Monish finds himself humming Rashi’s commentary to the melody he has heard Maria singing. Next, he meets her secretly at the outskirts of town, where she seduces him by asking him to swear his love by everything that he holds sacred. “Do you love me?” She asks, and he yields to her demands, swearing his love in ascending order by his rabbi, his parents, his ritual fringes and t’filin, . . . until finally by the Torah and by God Himself!

Satan and Lilith have their man. The hero who might have ushered in the redemption is instead nailed by his earlobe to the doorway of hell, the prescribed biblical punishment for a slave who refuses manumission.

Lamps—a thousand barrels full of pitch—/ the wicked are the wicks.

At the door, bound and fettered,/ our poor Monish lies.

The fire for his roasting is ready/ and the spear is poised!

(Translation by Seymour Levitan)

If Peretz tells us that he is Monish, did he think that he had betrayed Jewishness to deserve this punishment? Why would he launch his Yiddish literary career—and then his memoir—with the story of his damnation?

The modern Yiddish and Hebrew writers emerging from traditional society realized that new ideas and conditions needed new forms of expression. These included everything from racy potboilers of Shomer (pseudonym of Nokhem Meyer Shaykevitch) to massive novels of Sholem Asch, modeled on the Nobel-prize-winning works of Henryk Sienkiewicz and Wladyslaw Reymont; from the Austrian-styled operettas of Abraham Goldfaden to the Ibsen-like social dramas of Jacob Gordin. All writers, including Shakespeare and Dante, had routinely borrowed or “stolen” from others, and how else but through such adaptation could Jewish writers have created modern works in their own languages?

Peretz was alive to everything that was happening in European culture; literary scholars have enjoyed tracing many of his plots to local folktales, classics, and contemporary writings. In “Monish” he creates a miniature Faust who bargains away his soul to Mephistopheles, but in the semi-comic style of Heinrich Heine, the Jew who became one of Germany’s greatest lyric poets. Heine was confined to a culture that was not only alien but often hostile to Jewishness, and from that essential discord he developed a romantic irony that became all the rage in Europe, with special appeal to his fellow Jews—Peretz among them.

Heine is the only writer whose influence Peretz acknowledges—to the point of regret. Heine’s iconic image of the Jew was a prince named Israel whom an evil witch has transformed into a dog. All week long Israel feeds on garbage and on neighborhood taunts, until the arrival of “Princess Sabbath” restores him to human form, and rewards him with the Jewish version of a heavenly meal:

Cholent, light direct from heaven,/ Daughter of Elysium!/ Thus would Schiller’s Ode have sounded/ Had he ever tasted cholent.

Cholent is the delicacy/ That the Lord revealed to Moses,/ Teaching him the way to cook it/ On the summit of Mount Sinai. . . .

Cholent is God’s strictly kosher/ Certified and blessed ambrosia, Manna meant for Paradise,/ and so, compared with such an offering,

The ambrosia of the phony/ Heathen gods of ancient Greece/

(Who were devils in disguise) is/ Just a pile of devils’ droppings.

(Translation by Stephen Mitchell)

Heine brings the great Schiller’s “Ode to Joy” crashing to earth in the bean-stew of Jewish self-mockery, and with similar self-deprecation, Peretz explains why he cannot be Heine or Schiller:

Differently my song would ring, if for Gentiles I would sing—

Not in Yiddish, in zhargon,/ which has no proper sound or tone.

It has no word for sex appeal,/ and for such things as lovers feel.

Defining Yiddish ironically—one might say, as the language of cholent—Peretz was simultaneously claiming the cultural independence of Yiddish from German. Monish is under no witch’s spell. He actually is a princely heir to a civilization of moral refinement, who falls prey to a swindler whom any child should have been able to recognize. Peretz was that child and he mocks the part of him that had yielded without a struggle. This poem about Germany’s fisherman catching the Jew in his trap was so personal to Peretz that he revised it at least four times, each version more modernist in style and more cutting in its verdict.

The fable of the Polish Jew who capitulates to “Maria” is far more sinister to us today than when young Peretz felt himself conquered by Germany’s music.

III. Stage One

Calibrating how much Jews should resist or embrace Western civilization was part of the responsibility Peretz assumed as a Jewish writer. In one of his earliest stories, framed as a discussion between two yeshiva boys, Zelig, who has been reading Greek mythology, tries to explain to his friend Ḥaim that the phrase “as lovely as Venus,” is merely a comparison, “the way you might compare someone to Shulamith of the Song of Songs.” Ḥaim is enraged: how dare Zelig compare Venus, a deity that fornicates and murders, with the exalted heroine of the Bible? “How can profound thoughts be clothed in shabby comparisons?” The story ends with Ḥaim’s praise of Shulamith and his insistence that no one can be compared to her, “absolutely no one, do you hear?!”

Unlike in “Monish,” here Peretz has Ḥaim rejecting outright an aesthetics of immorality. Though Ḥaim is defensively rigid and Zelig open-minded, the story protests on the former’s behalf that the Jew dare not surrender his moral standards as part of acculturation. Heine had called baptism the entry ticket to European civilization, and Ḥaim won’t pay the price. The Jews had always recognized the difference between Greek gods and the God of Israel, and were they not obliged to keep doing so?

A greater Western temptation came to Peretz and his generation in the guise of moral progress. The French Revolution’s banner of liberty, equality, and brotherhood coupled with Marxism’s assurance that dialectical materialism was scientifically inevitable persuaded countless young Jews to form political movements that claimed to advance and transcend Jewish teachings. Thus, within Jewish communities, intramural struggles began that ran parallel to and intersected with those same divisions in European politics. In the 1890s, Peretz was decidedly on the Left, which meant sharing the excitement of the growing labor movement, women’s movement, and the clamor for social change.

This reorientation coincided with Peretz’s relocation in 1890 from his native Zamość to Warsaw. His first 37 eventful years had included various failed ventures such as a mill that went bankrupt, a failed marriage that had left him with custody of a son, Lucjan, and a brief career as an attorney—all while he was trying to establish himself as a Hebrew and Yiddish poet. Once in the metropolis, he found steady employ at the Gmina, the Warsaw Jewish Community Council, the counterpart of our Jewish Federations, work that exposed him to every aspect of local affairs and to some of the neediest Jews in the city. After workdays, he would turn to literature, channeling his impressions into stories, sketches, editorials, articles, poems, and screeds for the little magazines and anthologies that he edited and published. He became a magnet for aspiring Yiddish and Hebrew writers and for the young radicals who sought his support.

Peretz’s most famous story of his early years in Warsaw was “Bontshe Shvayg,” published first in a New York socialist newspaper in 1892. Bontshe is defined by his silence (shvayg is the imperative, be silent!): he never complains no matter how much he is abused by fate and by his fellow creatures. But Peretz was after more than an uncomplaining Job, and wanted more than sympathy for the good man who is forever mistreated. With this story he challenged his society’s mistaken notion of justice: if you think that there can be some compensation in heaven for injustice on earth, well think again. I will show you how wrong you are by playing out your fantasy, . . . and disabuse you of it forever.

When Bontshe dies, the Divine Court accords him the welcome it reserves for saints. His reception and trial are rendered with sympathy and wit, and the posthumous judgment is as fair as the folk imagination dictates. In return for the injustices he bore in silence, the sufferer is invited to take anything he desires. Bontshe asks for a buttered roll. The angels hang their heads in shame, and the prosecutor (i.e., Satan) has the last laugh. A man who cannot demand what he merits disappoints our need for a just world. Unless he develops the capacity to claim what he is owed, justice can never be served.

One can see how the emerging labor movement used this story to organize workers and why a Communist critic would later call this “the radical period in Peretz’s writing.” In dozens of stories and sketches, Peretz also exposed in stories more “realistic” than Bontshe’s the dire living and working conditions of most of the city’s quarter-million Jews whose numbers kept growing as more poured into Warsaw from the surrounding area. A young mother whose husband goes off to the study house instead of earning something to feed his family tries to hang herself in despondency, but can’t go through with it when the baby’s wailing calls her to try to nurse it. Another story shows the thwarted pleasure of newlyweds confined to an overcrowded cellar. Following up on some of the still-burning issues raised by the Jewish Enlightenment, Peretz condemned hypocrisies of Jewish religious practice that disadvantaged the poor. How could the system of dowries be allowed to determine the marital prospects of young seamstresses longing for a husband?

Of all the issues that engaged him, none gave Peretz more trouble than the relation between Jews and their fellow Poles. Sharing a coach with a Polish traveler in one of his stories, the narrator is not sure how far to trust the man’s warm sentiments about a Jewish woman he describes. Who can distinguish lascivious intentions from honest admiration? Peretz’s liberal hopes of Polish-Jewish brotherhood encouraged the very proximity and affection that his wariness of sexual predators—and of intermarriage—sometimes warned against.

Moral choices were not always clear-cut. The story, Pidyon shvuyim, “The Redemption of Captives,” dramatizes the Jewish obligation to pay for the release of fellow Jews from Gentile detention. Thus, when the husband of a devout Jewish couple is informed one winter night that a Jew and his family are being held by the local lord for ransom, he immediately takes some money and rushes to their rescue. But instead of money, the lord’s ransom demand is an hour alone with the Jew’s beautiful wife, with the promise not to violate her sexually. While the husband pays the price to redeem the family, he suffers the terror of his wife’s infidelity. Could their attraction have been mutual? The innocent resolution of the story does not erase the husband’s or our awareness of his political weakness and husbandly impotence in performance of this mitzvah. This redeemer of captives is very much a captive himself.

Though Peretz was not yet at the point of dealing openly with sexuality, he was obviously alert to the way erotic attraction complicates matters of right and wrong as well as relations between Jews and their Gentile neighbors, which he first broached in his tale of Monish and Maria. Peretz’s future biographers may also want to consider how his attraction to all things Polish correlated with his literary treatment of the subject. He courted his second wife Helena Ringelheim in Polish, and Polish remained their home language even as their apartment became the central address of Yiddish culture. People wondered whether Lucjan spoke Polish (he did) but the boy made clear his indifference to Jewishness. Such inconsistencies and tensions in his own life suggest why so much of Peretz’s work and thinking take the form of dichotomies, oppositions, and trials.

IV. Stage Two

Though never formally associated with any political movement, Peretz was imprisoned for several months in 1899 for having attended an outlawed socialist gathering. He had by then already veered away from the newly organized workers circles, disappointing the young radicals among his followers.

Jews and Poles alike (some prefer to say, Jews and other Poles) were torn in dizzying variations between competing ideas of left and right, class and nation, secular and religious, modern and traditional, liberal and conservative. Among the Jews, one additional fault line fell between those intent on leaving—be it for Argentina, Palestine, London, or New York—and those devoted to staying in Poland, which Jews had called home for almost a millennium. As between those headed dortn, elsewhere, and those remaining here, doh, Peretz was an essential doh’ist, fully immersed in the immediate life of Polish Jews and on securing a better future for all. This was probably the main reason he did not identify with the official Zionist movement though he published in some of its journals and shared its liberal ideals. His own national enthusiasm was stimulated by the fervor with which many of his Polish counterparts embraced their folklore and ethnography and used culture as a means of achieving national independence.

By the turn of the century, Peretz focused less on correcting social wrongs and more on reinvigorating Jewish values. Whereas he had once approached the ḥasidic movement with the impatience of an enlightened reformer, he now began adapting ḥasidic motifs for “stories in the ḥasidic manner,” drawing on the Jewish folktale tradition for a series of neo-folktales, Folkshtimlekhe geshikhtn. This was by no means a return from secularism to traditional Jewish observance that we associate with the term ba’al t’shuvah, nor was it a sentimental wish to recover a golden Jewish past. By drawing on indigenous religious and folk sources, he was laying the cultural foundation for a modern Jewish people that would continue to flourish in Poland and elsewhere, including in the Land of Israel.

Ḥasidic hagiography often extols the supernatural wonders that the rebbe performs, assuring his followers that they have an intercessor in heaven. Peretz’s story, “If Not Higher” follows that pattern while elevating the rebbe’s good deeds on earth above his alleged ability to intercede with the Almighty. The narrator is a skeptic, perhaps modeled on the author, and because he sets out to disprove the congregation’s belief in the rebbe’s supernatural powers, we trust the rebbe’s sanctity all the more when the narrator plays detective and after witnessing the actual earthly good the rebbe does, chooses to become his disciple.

Similarly, whereas folktales describe how the prophet Elijah magically helps struggling families in need, in Peretz’s story “Seven Good Years” the moral behavior of the couple that receives Elijah’s magical bounty is more impressive than the miracle he performs for them. All that husband and wife do with their good fortune is to ensure the Jewish education of their children.

Peretz adapted and invented these plots so delicately that readers had no reason to suspect his apikorses—the heretical deviation of the stories from the faith that had inspired the originals. Rather than expose belief in the supernatural as nonsensical superstition, as the enlighteners had done, Peretz magnifies the human accomplishment without necessarily denigrating the divine.

“Between Two Mountains” (1900) shows how Peretz could even turn a negative into a positive. In 1772 the Gaon of Vilna, the greatest rabbinic authority of his time, triggered the most divisive intramural conflict of the century when he issued the first of several bans against the emerging ḥasidic movement. Battles between Ḥasidim and Misnagdim, their opponents, consumed almost every township in Poland, leading to occasional violence and denunciations to tsarist authorities. In this story Shmaye the narrator, strategically situated between the warring camps, begins by telling us that the ḥasidic rebbe Noahke had once been the outstanding student of the misnagdic rabbi of Brisk. But Noahke found his teacher too elitist, too coldly rational, too distant from the common Jewish people, and established instead his own homier ḥasidic community in Biale. (This recapitulates the history of Ḥasidism, drawing on dozens of such accounts.) Shmaye, one of Noakhke’s followers, had moved to Biale to be near his rebbe, but found employment with a man whose son is married to the daughter of the rabbi of Brisk! Thus, when an emergency arises during the daughter’s labor and delivery, the Brisker rabbi is called for and when he arrives, Shmaye becomes the go-between for a meeting between the two antagonists.

Shmaye hopes for a reconciliation; Peretz aims for something finer and more historically plausible. Even as Shmaye’s sympathies lie with his rebbe’s lovingkindness, he is dazzled by the intellectual might of the conservative rabbi: “They did not reach an understanding. The Brisker rabbi remained a Misnaged, just as before. Yet their meeting did have some effect. The rabbi never again persecuted Ḥasidim.” Jewish greatness is proved able to sustain two equally powerful, contrasting forces and the Polish Jew is strong enough to withstand—and appreciate—the tension between them.

V. Stage Three

By the end of the 19th century, Yiddish literature had produced a classic triumvirate—Mendele Mokher Sforim, Sholem Aleichem, and I.L. Peretz. Too distinctive in their excellence to be ranked, they were distinguishable by region, the pair of Russian/Ukrainians as recognizably different from the Pole as the Russian/Ukrainian Gogol is from Polish/Lithuanian Adam Mickiewicz. Peretz thought self-mockery well and good, but not when other nations had begun to affirm their national independence, too often defining Jews as the unwelcome alien. Enlighteners and reformers—and Mendele the satirist and even Sholem Aleichem the humorist—threatened further to undermine Jewish moral self-confidence which badly needed reinforcement. Peretz himself had started out in the ironic tradition of Heine, but by 1900 he was less interested in deflating hypocrites and righting injustices than in seeking out virtues and capturing sparks of Jewish glory.

As a mood of national resurgence likewise spread among the Jews, Peretz emerged as a centrist leader. He argued for Jewish political representation in a democratically elected Polish government. His appeal to most of the ideological and organizational subdivisions in the Jewish world was to become manifest at the First International Conference on Yiddish convened in 1908 in Czernowitz (then Austria, now Ukraine). Yiddish was by then the vernacular of most of the world’s 17 million Jews, more Jews than had ever used the same language at any time in Jewish history. Modern Yiddish literature that had started out tentatively barely a half-century earlier now had its own publishing houses and newspapers on four continents. Millions of ordinary Jews were corresponding in Yiddish. The Conference was meant to celebrate and confirm the legitimacy of the language that some still disparaged as zhargon, jargon—not a “real” language at all.

The only member of the classic triumvirate who was able to attend the conference, Peretz proved indispensable in uniting the gathering. He urged the translation of the Hebrew Bible into modern Yiddish for that purpose, because Yiddish could not otherwise serve as the unifying language of all the Jews. Nonetheless, the linguist Joshua Fishman reminds us that such conferences “always ran the risk of becoming immersed in politics, . . . even if such topics were explicitly skirted by the conference planners.” Just so, Jewish socialists attempted to displace Hebrew by insisting that Yiddish be declared “the” rather than “a national language of the Jewish people.” Peretz drew on his authority to keep the original wording and preserve the linguistic balance that Mendele called as natural as breathing through both nostrils. All reports of the conference highlight his role as the rallying person in charge.

This Conference that was expected to be the first of many actually marked the high standing of Yiddish before it was sidelined by the Yishuv in Palestine as part of the unification of sovereign Israel, highjacked by the Bolsheviks as an instrument of Communism, and traded in by the vast majority of its speakers for the dominant languages wherever acculturation offered them real advancement. Indeed, Czernowitz proved in retrospect a rare attempt at national cohesion in the face of internal divisions and escalating external threats.

Meanwhile, in Warsaw, Peretz took advantage of loosening tsarist restrictions to work in every opening area of culture. Had he been granted different writing conditions, he might have written novels on the grand scale and done with Jewish Warsaw what Balzac did with Paris, or Dostoevsky with St. Petersburg. Too beleaguered and intellectually restless for such tomes, he used shorter forms and, without realizing that he sometimes tried to compress his flood of ideas into symbolic shorthand, expressed surprise when readers complained that they could not understand his stories. Ellipses—those three dots signifying incompletion or deliberate ambiguity—became his trademark.

He threw his energies into myriad projects, founded a choral society, encouraged modern Jewish schooling and adult education. With the liberalization of the Yiddish theater, he tried his hand at social drama, family saga, and modernist experiment. His plays in each of these modes remain more read than performed, still waiting for the right producers to realize their potential.

To give some sense of that potential, when Hillel Halkin published his English translation of Peretz’s last play, A Night in the Old Marketplace, in 1992, he tried to get an opera scored for this phantasmagoric, ambitious work that went well beyond anything Peretz had attempted before. In the manner of Luigi Pirandello, the cast includes the theatrical staff—director, stage manager, narrator, and poet—plus representatives of the entire Jewish population of Poland from factory workers and drunks to Ḥasidim and philosophers, the dead and the souls from purgatory, with gargoyles and statues speaking from the walls. Rather than any developmental plot, we hear voices in every timbre and kind of interaction, which may be what prompted Halkin’s idea of operatic performance. Peretz seemed to be summing up Polish Jewry in a comprehensive leave-taking from the beloved Zamość of his childhood.

When I crisscrossed that marketplace during breaks in the conference, I imagined Peretz’s characters speaking from the surrounding balconies, with the church bell pealing and the tin rooster crowing from the town hall tower. The play’s final curtain falls on the factory whistle drowning out the Jester—the badkhan—who is summoning Jews to the synagogue: “Jews, Go to shul!” In shul arayn! Critics argue over whether this was intended as the last call of a doomed civilization or the author’s genuine summons to Jews wherever they still thrive: Return before it is too late. Since “editorial comedian,” letz fun der redaktsye, is one of pen-names Peretz had assumed in his early publications, we can probably trust the Jester, without knowing how seriously he himself takes his summons.

VI. Coda

Whether the play’s ending should be read as a prophecy of doom or a call to repentance, it is a strikingly pessimistic note given the hopefulness that characterized so many of Peretz’s endeavors. He was after all born and raised in a Jewish liberal enclave of Poland, and was able to radiate faith in its creative survival for those who had lost their traditional touchstones of belief. He represents the Jewish liberal imagination before it was tempered by the deportation of Zamość Jewry to the Belzec death camp. Amid the devastation of the First World War, in Warsaw in 1915, an estimated 100,000 mourners flooded the streets for his funeral, while everywhere else Europe’s Jews had settled, he was memorialized in schools and cultural institutions. The I.L. Peretz Yiddish Writers’ Union was founded that year in New York, and shortly after, Peretz’s portrait was hung in the place of honor in the Yiddish PEN Club of Warsaw. “The golden chain” was the image Peretz used for the unbroken transmission of Jewishness through the generations, a chain that began with the biblical prophets and talmudic sages, and continued on with literary giants like Heine, Mendele, and Peretz himself. When the Yiddish poet Abraham Sutzkever survived the Vilna Ghetto and made his way to the Land of Israel, he established a literary journal and named it Di goldene keyt, The Golden Chain, in tribute to Peretz’s vision.

I never published the paper I presented at the conference on the pursuit of justice in Peretz’s work. In it I pointed out that Peretz never fully confronted the problem of evil, certainly not the kind of evil that could empty the marketplace of its Jews. But why not let the master speak for himself through one of his last stories, written 1915, the year he died?

“Yom Kippur in Hell” opens with a scene like that in “Monish” with a horse-drawn carriage rolling into town. This carriage is recognized as belonging to the dreaded Jewish police informer who must be on his way to the provincial capital to implicate some poor Jew in alleged criminal actions. Suddenly, the carriage stops and the townspeople discover that the informer is dead—dead of natural causes, right there in their midst! Jewish obligation takes precedence over revulsion. The Burial Society does what it must, and after the funeral the soul goes to the court of ultimate judgment.

Peretz has his usual fun with these double-decker stories. Naturally, the soul of the Jewish informer goes directly to hell, but when questioned by the gatekeepers about where he died, they cannot find the place in their registry. He says he died in Lahadam—acronym for Loy hoyu hadvorim l’oylam—or Neverwas—and indeed: hell has no record of such a town because apparently no one from that town has ever gone to hell. The devils that are dispatched to investigate discover that though its Jews are no better than those elsewhere, their cantor had a voice so exceptional that “as soon as he started to pray, the whole congregation repented of its sins with such fervor that all was forgiven and forgotten in heaven above. . . . Just say you were from Lahadam and no more questions were asked!”

This hell cannot tolerate. Satan, the principle of evil, uses his black magic to deprive the cantor of his voice, which leads to the concluding section of the story. The poor cantor desperately makes the rounds of religious healers, none of whom can restore what the devil has destroyed, but the rebbe of Apt assures him that his hoarseness will last only until death. “Your deathbed confession will be said in a voice that will reach to the far ends of heaven.” In other words, the cantor is assured his personal salvation without being able ever again to do the same for his fellow Jews. The outraged cantor vows revenge.

The next day the fishermen discover the cantor drowned. He had jumped off the bridge without saying his last confession, which lands him directly in hell. There he refuses to answer any questions, but since the demons know all about his case, they lead him to the boiling fire that stands in readiness—just as it did for Monish. At that moment the cantor recites the Kaddish—Yisgadal—in the special Yom Kippur melody in a voice even sweeter and tenderer than it had been on earth. From the cauldrons that had been reverberating with groans, voices take up the prayer. In an almost-reversal of “Bontshe Shvayg,” the cantor sings until all of hell’s inmates are singing with him, so fervently that their bodies are made whole again, their souls cleansed of sin. When he reaches the words, “May His name be blessed,” there echoes back such an amen chorus that the heavens open and the repentance of the damned reaches the divine seat of mercy. The sinners, now converted into saints, sprout wings and fly out of hell through the open doors of paradise. Only the devils remain in hell, and the cantor who as a suicide could not repent.

Peretz adds that naturally, hell eventually filled up again and became overcrowded despite added facilities. This is not about messianic redemption—only about one redemptive voice that refuses to be silenced. Peretz seems to have given us this rejoinder to the autobiographical poem that launched his career. Monish fell victim to Satan by betraying his people; the cantor defies Satan to rescue his people. Monish is in every way exceptional but for his ability to withstand the siren’s song; the cantor is in every way unexceptional but for the purity of his voice. Monish succumbs by singing Maria’s melody in place of his own. The cantor reserves his voice for a final act of self-sacrifice. Just as Peretz once modeled for Monish, so he lets us know through the cantor that the renaissance he inspired will not outlive his generation.

This neo-folktale is uniquely troubled. Starting with the Jewish informer whose death triggers the plot, Peretz concentrates on the strategies of evil. The cantor does no wrong, yet, as in Job, Satan exerts his sadistic will. Even the modest good the cantor does by preventing the damnation of the Jews is too much for Satan to allow. It is the function of the destroyer to destroy. Jewish resistance against such power is, to say the least, unequal. There can be no lasting salvation. No triumphant victory. Our savior can give us no more than temporary reprieve.

Peretz’s final literary testament is nonetheless defiant. With nothing more than clear voice and conscience, the cantor outmaneuvers Satan and wins some measure of justice. In truth, we gratefully grant Peretz far more credit than he claims for himself. He gave the Jews of Poland a temporary reprieve from the fires of hell, and us whatever he could salvage of their golden age.

Editors’ Note: Season Three of Ruth Wisse’s weekly podcast on Jewish literature, The Stories Jews Tell, will launch this fall and focus entirely on I.L. Peretz and his literary circle. You can listen to Seasons One and Two at https://storiesjewstell.com/.

More about: 6-weeks, Arts & Culture, I.L. Peretz, Literature, new-registrations, Yiddish literature