To mark the close of 2023, we asked several of our writers to name the best books they’ve read this year, and briefly to explain their choices. Some of their answers appear below. The rest will be appear tomorrow. (Unless otherwise noted, all books were published in 2023. Classic books are listed by their original publication dates.)

Elliott Abrams

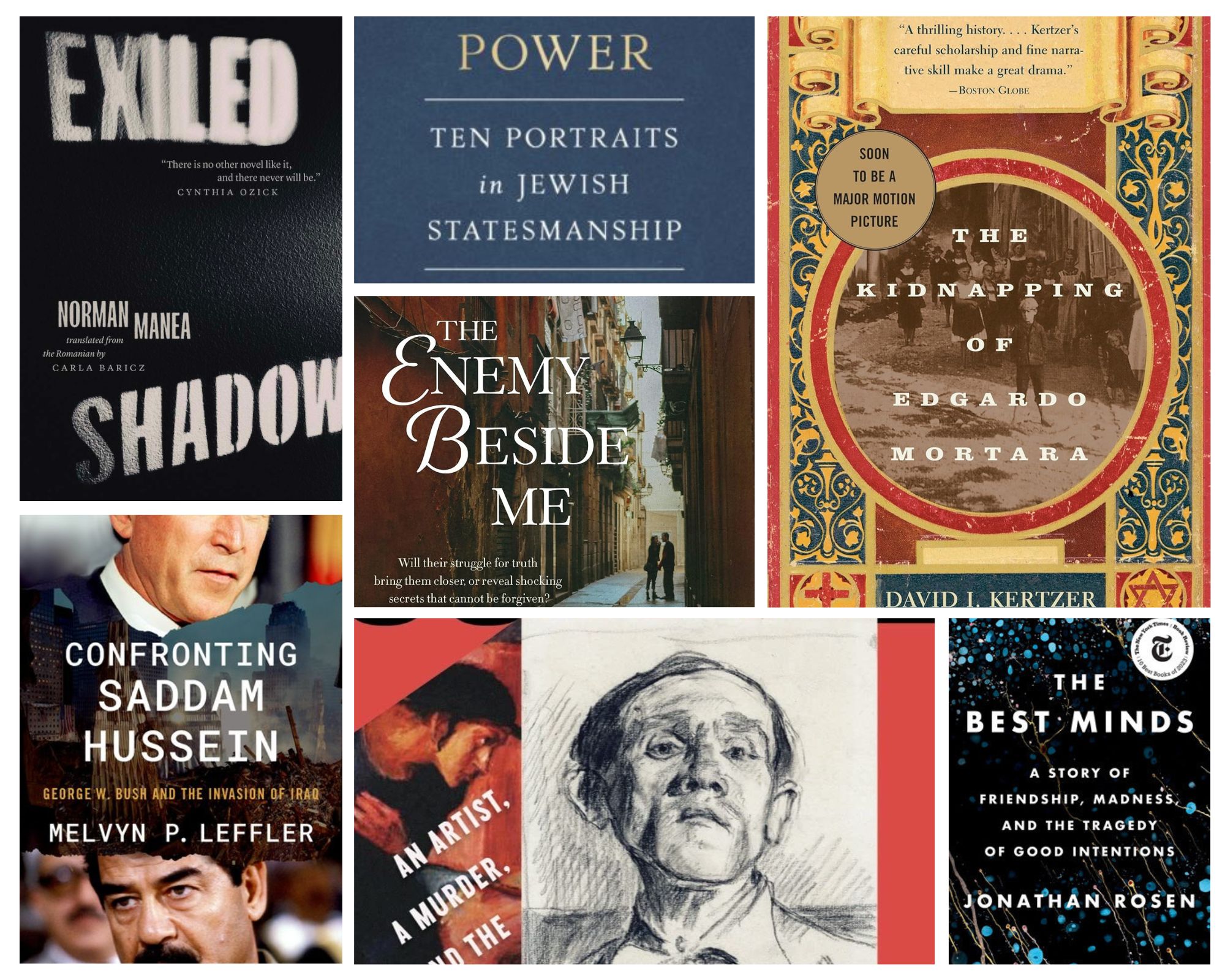

Bibi: My Story (Simon & Schuster, 2022, 736pp., $35) is Benjamin Netanyahu’s autobiography. Love him or hate him, he is a great historical figure in Israel’s past and present. The portrayal of the most recent years is inevitably too political, but the accounts of his childhood and earlier years in government are excellent.

The best book I’ve seen about the war in Iraq is Melvyn P. Leffler’s Confronting Saddam Hussein: George W. Bush and the Invasion of Iraq (Oxford, 368pp., $27.95). Scrupulously fair, comprehensive, and with a wonderful grasp of both the history and of how government actually works, it is essential for anyone who wishes to understand America’s war.

Israel’s Moment: International Support for and Opposition to Establishing the Jewish State, 1945–1949 (Cambridge, 2022, 450 pp., $32.99) by Jeffrey Herf tells the story of Israel’s establishment. Covering 1945–1949 in detail, Herf’s book explores how Zionists, anti-Zionists, Communist regimes, the leaders of the Yishuv, and European governments, combined with the internal battles in the United States government, made Israel’s birth an almost miraculous outcome on May 14, 1948.

Cynthia Ozick

- The Kidnapping of Edgardo Mortara, by David Kertzer (Knopf, 1997, 368pp., $17.72)

- The Popes Against the Jews: The Vatican’s Role in the Rise of Modern Anti-Semitism, by David Kertzer (Knopf, 2001, 355 pp., $17.95),

- The Pope at War: The Secret History of Pius XII, Mussolini, and Hitler, by David Kertzer (Random House, 2022, 672pp., $24.99)

- Bruno Schulz: An Artist, a Murder, and the Hijacking of History, by Benjamin Balint (W.W. Norton, 320pp., $30)

- Elie Wiesel: Confronting the Silence, by Joseph Berger (Yale, 360pp., $26.00)

- Exiled Shadow: A Novel in Collage, by Norman Manea (Yale, 376pp., $30)

Mosaic asks for a modest list of three books read in 2023, and here are (seemingly) an overly bold six. But of the six, three are so strongly allied that they may be regarded, in intent and execution, as one. Or, in fact, all six, however disparate in tone and temperament, have so much in common that all can be said to be possessed by an identical dybbuk: its name is Europe.

David Kertzer, the son of a World War II U.S. Army chaplain, is a historian who studies Vatican documents newly opened to public scrutiny. In three books, he uncovers, in prose with the pace of Tolstoyan revelation, the motives and powers of popes and inquisitors who rule over the intimately personal and communal lives of Jews under their reign. The chronicle of a Jewish child purported to have been secretly baptized by a Gentile house maid and seized by papal command from his parents to be trained to the priesthood has the force of tragedy, and far more: it leads to the unification of Italy. And the long-rumored suspicion of Pope Pius XII’s complicity in Hitler’s roundup of Jews is now fully confirmed in Kertzer’s The Pope at War. The Church’s record of anti-Jewish instigations—begun centuries before the advent of the confessionary Second Vatican Council (1962–65)—makes up the third of Kertzer’s trio on anti-Semitism; but they are neither polemics nor threnodies. They stand instead as the imperatives of scrupulous scholarship finally retrieved at the source.

Benjamin Balint’s biography of Bruno Schulz, the Polish Jewish writer and artist whose double force, as painter and master of what may be called the phantasmagoria of reality, is more than the story of a life obliterated in the streets of Drohobych during a German Aktion. It recounts a struggle for cultural ownership of the fairytale murals Schulz was compelled to paint on the wall of the room of a Gestapo officer’s child. Does Schulz’s legacy belong to Poland, or to the Jewish people, as represented by the state of Israel? The murals were absconded and are now on display at Yad Vashem in Jerusalem. Balint’s earlier study, Kafka’s Last Trial, has a not dissimilar theme: the struggle between Germany and Israel for linguistic proprietorship of the substantial Kafka papers Max Brod had salvaged and brought to Israel. Which has priority, which is more innate, Kafka’s German tongue or his Jewish affinities? These remnants of his work are today housed in the National Library of Israel.

Joseph Berger’s searching and often searing exploration of Elie Wiesel’s thought—an examination of principles and pledges, but also of informative year-by-year dailiness, the thickets of an evolving life. Berger returns us to Sighet, Wiesel’s native town, and takes us almost cinematically to the later scenes in the camps, where Wiesel witnesses a “fiery pit” into which living infants are thrown, too horrifying for some to believe, but later verified. The journalist becomes the novelist, the novelist the teacher, and the teacher, in the words of the Nobel, “the messenger to mankind.” But the strength of Berger’s work is in its dedicated particularity: telling what we never knew.

And if the voice of one of these six books can be said to capture the subterranean meaning of all of them, it is the Romanian Jewish writer Norman Manea’s wily and wise Nomadic Misanthrope who “deceived himself that he lived not in a country but a language,” in this instance Romanian—as Kafka lived in German, and Schulz in Polish, and Wiesel in French, Hebrew, Yiddish, and English; and as the six-year-old Edgardo Mortara from Bologna was made to live in the language of the catechism. The last word of Manea’s Exiled Shadow carries the defining admission of Jewish understanding: hineni, “Here I am.”

Neil Rogachevsky

It is difficult to present an unbiased assessment of my boss and colleague Meir Soloveichik’s Providence and Power: Ten Portraits in Jewish Statesmanship (Encounter, 232pp., $29.99). Over several years, I was lucky enough to have heard Soloveichik test drive his provocative insights into Jewish statesmanship in the stately classrooms of Yeshiva University. It is vital for the Jewish future that sources of political prudence and wisdom be recovered from within the Jewish tradition itself. Soloveichik’s book is a major contribution to that burgeoning effort.

Oren Kessler’s Palestine 1936: The Great Revolt and the Roots of the Middle East Conflict (Rowman & Littlefield, 334 pp, $21.63) is a rigorous but very readable narrative of the Great Arab Revolt in British Palestine. Kessler’s deft history reminds us that certain aspects of the Israel-Arab conflict remain drearily constant, notwithstanding the vast chasm of time and political circumstance separating 1936 and 2023.

Just as I was thinking about my choices for books of the year, news arrived that the Hebrew University political theorist Shlomo Avineri had passed away. Among his many works, I would like to recommend his Herzl: Theodor Herzl and the Foundation of the Jewish State (Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2013, 274pp., $31.57), the best biography of this great figure, and The Making of Modern Zionism: The Intellectual Origins of the Jewish State (Basic, 2017, 304pp., $19.99), a deep investigation of Zionism at the level of political theory.

Ruth R. Wisse

Not every writer is granted a plot as dramatic as the spiral into schizophrenia that befell Jonathan Rosen’s closest childhood friend. Rosen makes of this experience an extraordinary book. The Best Minds: A Story of Friendship, Madness, and the Tragedy of Good Intentions (Penguin, 576pp, $32) is autobiography, dense cultural history, and a welcome revisionist study of a mental illness that has been treated more often with good intentions than with reliable supervision. Not seduced by Allen Ginsberg’s saccharine idolizing of “angelheaded hipsters,” Rosen shows innocence paying heavily for the indulgence of madness.

Rick Richman wrote And None Shall Make Them Afraid: Eight Stories of the Modern State of Israel (Encounter, 388pp., $24.49) to remind us of the heroic phase of Zionism, which may have to keep producing heroes if Jewish sovereignty is to endure. Individuals have played a decisive role in securing statehood, and among them have been four very different Americans: the Supreme Court justice Louis Brandeis, who assumed Zionist leadership; Golda Meir, Israel’s fourth prime minister; the screenwriter and wartime publicist Ben Hecht; and Ron Dermer, currently Israel’s minister of strategic affairs. Though there is nothing didactic about this lively historical study, it is good to be reminded that American Jews were and remain partners in building and securing the Jewish homeland.

Teaching the truth about the murder of the Jews in the Second World War is a sacred trust for Jews but morally threatening to Europeans who took part in the carnage. In Naomi Ragen’s novel The Enemy Beside Me (Griffin, 400pp., $24.99), a male Lithuanian educator invites a female Israeli scholar of the Holocaust to help him make Lithuanian schoolchildren face their nation’s past. They have us readers sitting in those classrooms listening to historical depositions about what locals did to their Jewish neighbors: recitations that we—let alone those students—can hardly bear to hear. The novel’s stock romantic attachment between the classroom’s two adults is provocatively at odds with the underlying, and irreconcilable, national tensions.

More about: Arts & Culture, Best Books of the Year, History & Ideas, Literature