“If I had to select a single person to stand for East European Jews in America, it would be Abraham Cahan.”—Nathan Glazer

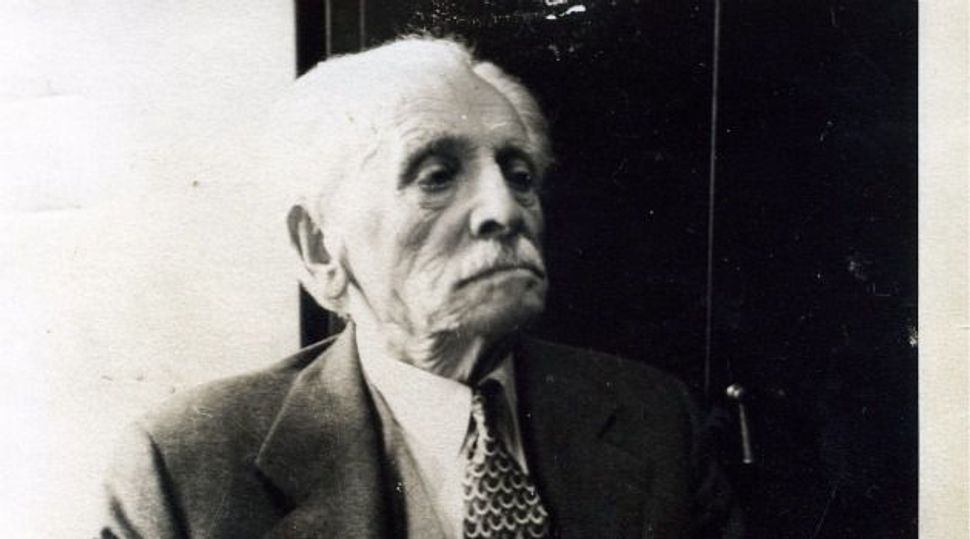

Nathan Glazer’s choice of who best represents the millions of American Jews from Eastern Europe highlights a profession as well as an individual. Was Cahan a politician? Rabbi? Business entrepreneur or philanthropist? Glazer himself was a sociologist, writer, and editor, so not surprisingly he singled out someone in the world of ideas. Abraham Cahan, co-founder of the Yiddish daily Forverts in 1897 and its editor from 1903 until his death in 1951, was one of the greatest newspapermen of that great age of newspapers, but he was more interesting to Glazer as an independent thinker, the first of a new American-Jewish breed. That recent events have revealed great moral, aesthetic, and political confusion in our own age suggests that Cahan’s model of intellectual life could use remembering and learning from—or at least remembering and lamenting its demise.

The twenty-two-year-old who landed in New York in June 1882 was in some respects typical of the Jews who immigrated in what turned into, over the next quarter-century, the largest migration in Jewish history. Young, single, and raised in a traditional Jewish home, he couldn’t wait to exercise the freedoms that he had been denied in Russia, which included release from Jewish observance now that he was away from the supervision of family and community, and the right to preach revolutionary ideals that were forbidden in his native land. Though Cahan had no part in the assassination of Tsar Alexander II in St Petersburg on March 13, 1881, the roundup of suspected radicals in its wake had dictated his rapid departure from Russia. His political ideas had been formed under Russian political oppression.

Cahan’s arrival coincided so neatly with the beginnings of unionization in the industrial northeast that he was almost immediately able to put his Marxist principles to work. The problems he encountered were real: they included an overcrowded city, dislocation caused by internal and transatlantic migration, unregulated industrialization, and dangerous working conditions. Behind the statistics governing this urban crisis were hundreds of thousands of actual people trying to find work that would give them food and shelter. Real, too, was the eagerness that some of the young immigrants had brought with them for fixing the alleged abuses of capitalism. Within a decade Cahan had stepped out as a leading spokesman of the growing socialist and labor movements.

Cahan described his first years in America in a five-volume Yiddish autobiography, Bleter fun mayn lebn (Pages From My Life), that doubles as a first-rate work of labor history. From the start he was on parallel missions to adjust to the country and to improve it. He wrote for the emerging Yiddish socialist press and became a featured speaker at union rallies. He entered into a life-long marriage with a highly educated fellow Russian immigrant, Anna Bronstein, that produced no children, as though to rivet him solely to his work. When Janet Hadda, a Yiddish scholar and practicing psychoanalyst, later set out to uncover a deeper stratum in Cahan’s life, she found nothing to excavate beyond what he himself had revealed. His trust in literary realism reflected his core belief that one could honestly “hold up a mirror to life” and thereby help to improve it. As a practical measure, although speechmaking in the immigrant community was then conducted in Russian, and though his Russian was fluent, Cahan became one of the most effective spokesmen for socialism by lecturing in the Yiddish immigrant vernacular.

In his own Yiddish memoir, My 50 Years in America, the playwright Leon Kobrin, who recognized drama when he saw it, describes Cahan’s appearance during a strike in Philadelphia in 1892 in his earliest years as an activist. The organizers of the rally had tricked some of the non-striking girls into coming and had seated them in the front rows just before the speaker was brought on stage. Playing his part to perfection, Cahan flew into a rage, stamping his feet, flinging his arms about and shouting that they ought to be laid down and whipped—“skinned alive” for scabbing instead of standing up to their bloodsucking bosses. Kobrin writes that he was reminded of the maggid of Kelm, the fiery preacher from Cahan’s native region of Russia whose sermons about the hellfire awaiting sinners were a byword for punishing rhetoric. But the tactic worked, and the scabs signed up for the union, while the crowd hailed Cahan as the “prophet” of their movement.

Nonetheless, Cahan was not meant to be a union organizer and, once he began writing for the Yiddish press, he developed a style better suited to literary persuasion, adjusting those shock-and-awe tactics to the harder task of winning a mass audience. “Was it possible to issue a daily paper in Yiddish that would nurture an intimate relationship with the masses while also trying seriously to raise their social and cultural awareness?” Irving Howe, a socialist of the next generation, admired how Cahan managed it, for example, by editorializing as “the proletarian preacher,” using the weekly Torah reading as the basis of his socialist messages. It worked because Cahan keenly felt and shared with his readers an enduring connection between their European past and their American future.

I. The Mediator

One of the great and best-known contributions Jews have made to the world as a result of their involuntary dispersion was the quickening of trade and commerce in goods. The same if not more goes for ideas. No Jew ever served in this role of farmitler—the Yiddish term for go-between or intermediary—more successfully than Cahan did in introducing European Jews to America and America to the Jews. Such intermediaries usually work only in one direction—helping those of their native culture adjust to their new one—but Cahan became equally adept at familiarizing Americans with his fellow immigrants and helping Jews feel at home in America.

On arriving in New York, Cahan had determined to become as fully literate in English as he was in Russian, which required mastering everything the cultivated American might be expected to know. He read Dickensian novels, studied the history of the United States, and after acquainting himself with important American writers of his day, got to know some of them personally. English was his fifth language after Hebrew, German, Yiddish, and Russian, and the third language he used in writing. Even as he was rallying workers in Yiddish, he was simultaneously placing articles in the local English press.

One day Cahan received a note from William Dean Howells, a famous New England writer whom he had been reading with interest. As opposed to Americans like Henry Adams—and, later, Ezra Pound and T.S. Eliot—who were appalled by the way the immigrant Jews were supposedly coarsening America and its language, Howells was curious about the rise of the Yiddish press and he sought out Cahan, who was then editing the socialist newspaper Arbeiter Zeitung. Cahan admired Howells’s novels, so when the two got together, they discussed literature as equals, the young immigrant filling Howells in on Russian literature and the “Dean of American Letters” encouraging the talented newcomer to publish his own fiction.

That was all the push Cahan needed. He began writing about immigrant life in English just as he had been doing in Yiddish. His biographer Seth Lipsky notes that in 1896, “Cahan’s first novel, Yekl: A Tale of the New York Ghetto, was brought out by [Appleton], the publisher of the famous grammar book that he had used to learn English only fourteen years earlier.” Cahan obviously did not consider himself part of that ghetto, whose inhabitants he rendered speaking broken English and still following old-world customs. Literary realism was his way of familiarizing Americans with parts of society they would otherwise not know.

In 1897 Cahan co-founded a new paper, the Yiddish daily Forverts, but quit when it became entangled in a fight for political control. He then made a very bold move. With connections he had made through Howells, he joined the staff of the Commercial Examiner, one of the smaller New York papers that specialized in keen local reporting. While there, he introduced his fellow journalists to the creative life and personalities of the immigrant community—one result of which was a classic of sympathetic reportage, Hutchins Hapgood’s Spirit of the Ghetto (1902). Cahan realized that he had as much to teach the other journalists as he had to learn from them:

My firm convictions and outspoken taste in literature, my passionate interest in art, and the excitable way I used to marshal my arguments—all this was unusual in American discussions about literature. Such things are discussed in America in a light, casual tone. But I took them with great seriousness. Thus, my words used to make an impression on my colleagues. During the afternoon discussions around the long black reporters’ table I was the center.

America had as yet no equivalent for the East European intelligentsia—highly educated, politically disenfranchised men and the occasional woman who believed that ideas determined the course of history. The best of American thinkers from the beginning had and continued to have the option of going into government; they had forged the country’s brilliant constitutional framework and continued to supply it with impressive leaders. By contrast, modern Russian youth with no such access were inspired to challenge, oppose, and ultimately overthrow the government. Although he was still relatively alone in taking it up, this role comes closest to defining how Cahan intended to function through the new medium of the daily newspaper. Though he by no means conceived of challenging the government, he was convinced that socialism would improve the country, and dedicated himself to the production of ideas that would lead to that end.

II. Mediating Novelist

After fifteen years of this work, Cahan had fulfilled his goal: he and his ideas had become influential in the wider culture. In 1913, when the popular illustrated monthly magazine McClure’s wanted to introduce its readers to the Jewish immigrant world, they went to its best-known guide. The articles Cahan duly submitted, under the series title “The Autobiography of an American Jew,” were so successful that he developed them into The Rise of David Levinsky (1917), a novel that shows off Cahan’s genius as cultural go-between. Modeled on Howells’s novel The Rise of Silas Lapham (1885)—the story of a simple Vermonter whose rise to wealth as a paint manufacturer precipitates a crisis of conscience that he nobly resolves at the expense of his business—Levinsky tracks a Jewish immigrant who arrives in 1885 with four cents in his pocket to become “worth more than two million dollars and recognized as one of the two or three leading men in the cloak-and-suit trade in the United States.” Far from touting his originality, Cahan explicitly placed his work in the continuum of American fiction, offering a Jewish version of the familiar rags to riches tale.

Levinsky as narrator tries to put his American readers at ease with the foreign aspects of his life. “I understand that some schoolteachers in certain villages of New England get their board on the rotation plan, dining each day in the week with another family,” he says. “This is exactly the way a poor Talmud student gets his sustenance in Russia, the system being called, ‘eating days.’” Cahan explains his intense Talmud schooling back in the old country in a way that flatters the Yankee support of education, and he does something similar in describing how newcomers feel about this promised land.

When the discoverers of America saw land at last they fell on their knees and a hymn of thanksgiving burst from their souls. The scene, which is one of the most thrilling in history, repeats itself in the heart of every immigrant as he comes in sight of the American shores. I am at a loss to convey the peculiar state of mind that the experience created in me.

When it comes to portraying life on the Lower East Side, Cahan does not try to replicate its speech, as he did in Yekl, because the goal here is to domesticate the exotic and to integrate the alien. Acculturation is not merely the subject of this book but its demonstration. Cahan had become part of America and the at-homeness he has come to feel he also wants to share.

While expanding his articles into a complete novel, Cahan had to show what lay behind Levinsky’s actions. For this he drew on some of his own experience, granting us more insight into his inner life than we would ever glean from another source. Some of the qualities Cahan ascribes to Levinsky’s success in business obviously resemble tactics the former used in outmaneuvering his newspaper competitors. Most of all, we sense Cahan’s presence in Levinsky’s wish that he could have devoted himself to learning, Torah mastery being the highest status in the traditional Jewish hierarchy of values, and intellectual work its closest secular equivalent.

The Rise of David Levinsky impressed the next generation of Jewish intellectuals more fully than it did Cahan’s contemporaries. The midcentury Jewish critic Leslie Fiedler, born in 1917, the year the novel was published, called it in 1959

a commentary on the rise of the garment industry and its impact on American life; a study of the crisis in American Jewish society when the first wave of German immigrants were being overwhelmed by Jews from Galicia and the Russian Pale; a case-history of the expense of the spirit involved in changing languages and cultures; a portrayal of New World secularism which made of City College a Third Temple, and of Zionism and Marxism, enlightened religions for those hungry for an orthodoxy without God.

At the same time, Fiedler also identified loneliness as the central feature of the book. “Like Peretz,” he writes, comparing Cahan to the great Yiddish writer whose stories he had published in the Arbeiter Zeitung, “he considers the vestiges of ghetto Puritanism one of the hindrances that stand between the Jew and his full humanity.” Fiedler uncovered in the novel a Jewish version of the theories he was then developing about suppressed eroticism in American fiction. This version starts when Levinsky as a teenaged Talmud student is warned against the sexual temptations of Satan. It continues when his strongest emotional connection is with his mother, who dies trying to protect him and for whom Levinsky can never find a satisfying substitute in love, trust, or companionship. His unsatisfactory relationships with women and failed attempts to secure marriage and family run parallel to his growing business success, suggesting that the failure of the former is punishment for the latter. In this way, Levinsky became one of Fiedler’s prooftexts for the theme of “love and death in the American novel.”

A bit after Fiedler, Isaac Rosenfeld, another great American Jewish writer, traced Levinsky’s “loneliness” to something more than sexual repression. Levinsky could not feel at home with his desires nor take pleasure in success because his character was formed by hunger:

Because hunger is strong in him, he must always strive to relieve it; but precisely because it is strong, it has to be preserved. It owes its strength to the fact that for so many years everything that influences Levinsky most deeply—say, piety and mother love—was inseparable from it. For hunger in this broader, rather metaphysical sense of the term that I have been using, is not only the state of tension out of which the desires for relief and betterment spring; precisely because the desires are formed under its sign, they become assimilated to it, and convert it into the prime source of all value, so that man, in pursuit of whatever he considers pleasurable and good, seeks to return to his yearning as much as he does to escape it.

Rosenfeld’s idea of metaphysical hunger went far beyond Fiedler’s theme of sexual repression. Like a rabbi commenting on a biblical passage, Rosenfeld thinks that all of Jewish history is marked by this twist—that this is a “profoundly Jewish trait.” The yearning for the Land of Israel that runs through Jewish history is that same reflexive desire, becoming its own object. According to Rosenfeld, the yearning in the Jewish saying, “If I forget thee, O Jerusalem . . . ,” is itself Jerusalem, and it is to that yearning most of all that we remain faithful. He extends his psychoanalytic insight into Levinsky’s character to the Jewish nation as a whole, as if to explain why Jews were prepared to long for Zion without necessarily moving there: return to the land was no simple desire to be fulfilled, it was the yearning for the land that had to be preserved. This theory about why Jews remain a Diaspora people makes Levinsky the embodiment of Diaspora man.

But Rosenfeld was not done. He is struck by the way Levinsky feels so very American. Americans are equally ambivalent about striving and fulfilment. “Our favorite representation of the rich is of a class that doesn’t know what to do with its money,” Rosenfeld writes. Levinsky and the American businessman he represents are similarly lonely because they are able to satisfy everything but the hunger that drove them to strive for success in the first place. “I am not suggesting that Jewish and American character are identical,” he continues, “for the Levinsky who arrived in New York with four cents in his pocket was as unlike an American as anyone could possibly be: but there is a complementary relation between the two which, so far as I know, no other novel has brought out so clearly.”

Cahan’s novel, begun as an attempt to make the immigrant Jews appreciated by their American compatriots, made the children of those Jews understandable to themselves. They recognized Levinsky’s moral kinship with not only Silas Lapham but also with The Great Gatsby, whose deeper theme of loss continues to resonate powerfully with the American public. Their interpretations of the novel in turn become part of its legacy, just the same as with these interpretations of Levinsky.

III. Immigrant Guide

So far, we have shown Cahan introducing Jewish immigrants to their fellow Americans. He was of course far better known, and remains so, for having acclimated the Jews to America as editor of the Forward. With the same instinct that Levinsky has for what style of coat will appeal to buyers and how to market it, Cahan found ways to engage his readers, by becoming the Forward’s guide to the new American perplexed.

In a wonderful section of The Downtown Jews (1969), his study of the immigrant generation (based heavily on Cahan’s life and writing), the historian Ronald Sanders describes the way Cahan took the idea of an advice column from a rival Yiddish newspaper and turned it into his paper’s most popular feature, the Bintel Brief (Bundle of Letters), in which he answered requests for assistance from men and women who were experiencing what he had so recently gone through himself. To a newcomer who was not yet earning a living wage yet was torn with guilt for not being back in Russia to help topple the tsar, Cahan writes, “Well, we can give no better advice than to fight right here in America for a social order in which a man wouldn’t have to work like a mule for five dollars a week.” Sanders thinks there were no more fictions left for Cahan to invent, that “his task was now simply to assemble his characters on stage, life’s editor.”

The fictional David Levinsky disappoints Matilda, the woman he had set out to impress, when she discovers that he has given up his ideals of study for the crass success of a manufacturer. Some such sellout of idealism was the standard indictment of anti-capitalist literature. The Marxist motto of the Forverts remained inscribed on its ears (the two top corners of the front page): “Workers of the world unite—you have nothing to lose but your chains.” Cahan, on the other hand, showed his independence by adjusting his youthful ideology to the actual challenges facing the Jews and America.

First among these challenges was the rise of Zionism. This turned out to be relatively easy to accommodate: the Jewish socialism on which Cahan had founded the Forverts acknowledged no necessary contradiction between commitment to the Jewish people and to the international proletariat or between Marxism and American democracy. What might have seemed a dubious project in 1897, when Herzl founded the Zionist movement—the same year as the founding of both the anti-Zionist Jewish socialist Bund and the Forverts—had become much more credible by 1917, when Britain issued the Balfour Declaration supporting the creation of a home for the Jewish people in Palestine.

By then, the carnage of the First World War that trapped Jewish communities between the warring armies had proven the Jews’ need for their own homeland. Like nationalists in many other emerging states, Jewish leaders began pressing for political independence. Young pioneers flocked to new Jewish settlements and cities of Palestine to drain the swamps, till the fields, replant the trees, and create a refuge from persecution. Necessity mothered invention as the Jews of Palestine developed self-defense against Arab attack and reclaimed Hebrew as the old-new language of a sovereign Jewish land.

Cahan’s authority as a man of the left and editor of the world’s largest-circulation Jewish newspaper meant that his growing respect for Zionism furthered the movement. In 1925, when he went to see for himself what was happening in Palestine, his reporting from there was deemed “a decisive moment in the history of American Jewry’s support for what many considered the Jewish homeland.” Leaders of the Yishuv, the Jewish community in Palestine, took heart from his support, which firmed up ties between the Histadrut, Israel’s central labor union, and the non-Communist unions in the United States. Meanwhile, the paper kept distancing itself ever further from the anti-Zionist positions of the socialist Bund and the Communists.

Indeed, no less consequential than his growing appreciation for the recovery of Jewish sovereignty in the Land of Israel was Cahan’s evolving response to the Russian Revolution, which he originally hailed as the fulfilment of his youthful dreams. In overthrowing the tsarist regime, the Revolution captured the allegiance of many Jews, who believed that it would end anti-Semitism and bring peace to the world. Then shortly after came the Bolshevik takeover, which set in motion plans for world revolution propelled by the Communist International. The Communists established their first beachhead in New York through the Yiddish daily Freiheit, which feigned independence while its dedicated editors enforced the Moscow party line. As this happened, the Forward’s original response to the Revolution—headlines proclaiming “a free Russian people, a free Jewish people in Russia!” and “Jewish Troubles are at an End!”—quickly turned to dismay at Lenin’s imposition of authoritarian rule.

Jews have often been credited or blamed for influence that they never had. Yet in America, they really did play an outsized role in both the spread of Communism and in resistance to it. The more anti-Semitism threatened the Jews, the more susceptible they were to the Soviets’ claim that they alone could defeat fascism in Europe. Like the immigrant who felt guilty about not helping topple the tsar, many believed that Communism would solve the “contradictions of capitalism” in the United States. To this day, historians have not shown in full how successfully the Soviets organized and promoted international protest against the trials of the anarchists Sacco and Vanzetti in the 1920s, the Scottsboro boys in the 1930s, and the Rosenbergs in 1951 (in the latter case even ensuring the conviction of the accused to make their point about American discrimination and injustice). Anti-American campaigns also redirected attention away from the escalating criminality of Soviet rulers.

Cahan’s resistance to Communism became increasingly important given the receptivity of the American Yiddish cultural elites to its spread. In August 1929, the mufti of Jerusalem incited massive attacks against the Jews of Palestine that recalled the worst pogroms of Europe. Joseph Stalin, by then the sole leader of the USSR, hailed this aggression as the start of an Arab revolution against British and Zionist imperialism. This became the basis of anti-Zionism, which replaced discredited forms of explicit anti-Semitism after Hitler’s erasure of the Jews of Europe. In the heat of the moment, Soviet support for Arab terror shocked many of its Jewish sympathizers into severing their ties with the Freiheit and propelled many of its writers and readers to the Forverts.

Cahan’s opposition, though deep, was not easy; it reflected great personal anguish and disillusionment. Russia was his homeland, its liberation his youthful ideal and socialism its instrument. His response to hardening Stalinist repression was not a triumphant “I told you so!” but rather a lamenting “Who could have imagined this?”

Meanwhile, many Yiddishists, for whom the language had become the vehicle of Judaism, as well as some Yiddish writers who depended on Soviet support, quickly scrambled back into the Soviet fold. Then they challenged the likes of Cahan. “If with a knife at our throat we would have to choose: you [the Zionists] or the Yevsekten [the Jewish Bolsheviks], we will choose the Yevsekten,” wrote two leading Yiddish poets. This is

not because they please us, they don’t. But they are young and behind them stands a great and fruitful idea. If they are blind in certain things, they may in time begin to see; . . . they have the potential. YOUR camp is the generation of the desert, in every respect. It is perhaps brutal to say so but—your time has passed, in truth, forever.

In the name of progress, and despite their abhorrence of one or another Soviet action, important poets like Menahem Boreisho and H. Leivick welcomed Communist support for Yiddish as the sanctioned language of the Jewish proletariat. And the more confidently Cahan discredited Stalinism, the more he was accused selling out to bourgeois interests and to Zionist reactionaries. There is no doubt that Communism would have made much more dangerous inroads in America without him.

IV. American Jew, Jewish American

Indeed, of all his intellectual roles, Cahan’s most important legacy turned out to be this evolution from proletarian preacher to guardian of America and Zion. As editor of the world’s largest-circulation Jewish newspaper, his was almost certainly the most influential Jewish voice in America of the interwar years; it mattered enormously that he came to choose Zionism over Communism and American democracy over Soviet dictatorship.

The interwar years ended on September 1, 1939 with Germany’s attack on Poland. Yet the shock of the Soviet-Nazi pact to divide Poland between them was for many on the left a greater one than the invasion itself. If ever the presence of a Yiddish newspaper proved its worth, it was with its coverage of what the historian Lucy Dawidowicz called “the war against the Jews,” and of the rise of Israel in its aftermath.

With the outbreak of war, Cahan vetoed plans to celebrate his impending 80th birthday. Nonetheless, Forverts insiders insisted on publishing a tribute book from which we may draw our summary of his achievements.

- As leader: “Founders are never zaydene yungermanchikes,” wrote his fellow former revolutionary Raphael Abramovitch, echoing their youthful disdain for the “silken young gentlemen” who never dirtied their hands. Transposing into positive terms what others called Cahan’s tyrannical rule, he praised Cahan’s “strong and determined will, superhuman energy, extraordinary stubbornness and tenacity, and an amazing tireless urge to work”—all the indispensable qualities of a pioneer.

- As editor: “I know of no case when a newspaper played such a prominent [political] role as the Forverts did in the Jewish workers’ movement,” went another tribute. Socialists found him wanting, but the ten-floor Forward building—erected thanks to his leadership—testified as much to the growth of the labor movement it had championed as to the paper’s own success.

- As belletrist: his novels in Yiddish and English were all translated into and widely read in Russian, and his reportage from Europe and Palestine created a bond between those who needed help and those who could provide it.

- As literary critic: “In his art he is not a propagandist.” His admirers recalled his significant theater and literary criticism, which measured Yiddish by the highest literary standards. Intellectuals are expected to set expectations.

- As literary impresario: Cahan supported Yiddish writing from the early work of I.L. Peretz (which he published in America before it appeared in Poland) to the novels of Sholem Asch, the brothers Israel Joshua and Isaac Bashevis Singer, and many hundreds of poems, stories, and other serialized fiction by some of the finest writers of the interwar years.

These tributes from those who knew him best acknowledge that Cahan was right where others—themselves included—had accused him of being wrong. David Einhorn, a fine writer whom Cahan had published from Europe and helped bring to America, singles out Cahan’s courage in preparing the immigrant generation for its “necessarily difficult transition:”

We live in a time when all values are being reassessed and we see the past nakedly. Whoever once counted as a realist, a materialist, turns out to have been an idealist, and whoever preened in his idealism turns out to have been an egoist thinking only of himself and his interests. Those who fought against the Forverts had least concern for the Yiddish masses in America and elsewhere.

The same qualities that made him a hard editor and unlovable boss helped Cahan withstand assaults from the left, much like those later aimed at his successors of the next generations. Three decades after Cahan’s death in 1951, Seth Lipsky, one of the boldest newspapermen of his day, undertook to run the English Forward in Cahan’s spirit. Alas, Lipsky was forced out by the old socialist-Yiddishist management, who returned it to the ideas that Cahan had outgrown long before. (Lipsky went on to revive another New York paper, the Sun, and to write an inspiring biography of the man who inspired him.)

The overarching question for Cahan’s immigrant cohort and their offspring was the fate of Jews in this golden land of their dispersion. Cahan arrived with one set of ideas and came to realize that Jewish loyalty corresponded with appreciation of America, and that both were indisputably good. The first hint of this realization he expressed through his eponymous antitype, the cloak-manufacturer David Levinsky.

Wealthy and a leader of industry, Levinsky is vacationing at a hotel in the Catskills that serves newly established Jews like himself. The noise is so unbearable that when David shuts his eyes, he is reminded of the stock exchange. The poor musicians cannot make themselves heard over the noise, whether they play from Aida or hits of the Yiddish stage. As a last resort the conductor strikes up “The Star-Spangled Banner” and the effect is electrifying—on the crowd and on the novel:

The few hundred diners rose like one man, applauding. The children and many of the adults caught up the tune joyously, passionately. It was an interesting scene. Men and women were offering thanksgiving to the flag under which they were eating this good dinner, wearing these expensive clothes. There was the jingle of newly-acquired dollars in our applause. But there was something else in it as well. Many of those who were now paying tribute to the Stars and Stripes were listening to the tune with grave, solemn mien. It was as if they were saying: “We are not persecuted under this flag. At last we have found a home.”

Love for America blazed up in my soul. I shouted to the musicians, “My Country,” and the cry spread like wild-fire. The musicians obeyed and we all sang the anthem from the bottom of our souls.

Intellectuals do not normally strike up the band, but Cahan did well to direct his audience away from the bad and toward the better. It’s a direction many an intellectual today, Jewish or otherwise, could stand to learn from. Cahan, who moved to America from an autocratic Russia when he was twenty-two, knew what a democracy meant, and repaid the possibilities he saw in it by building it up—by offering to American culture a civic energy, a model of intellectualism, and a Jewish sense of historical experience.

Ruth Wisse’s writing in Mosaic is made possible by the generosity of Robert L. Friedman.

More about: Abraham Cahan, American Judaism, Forward, History & Ideas, New York Intellectuals, Yiddish