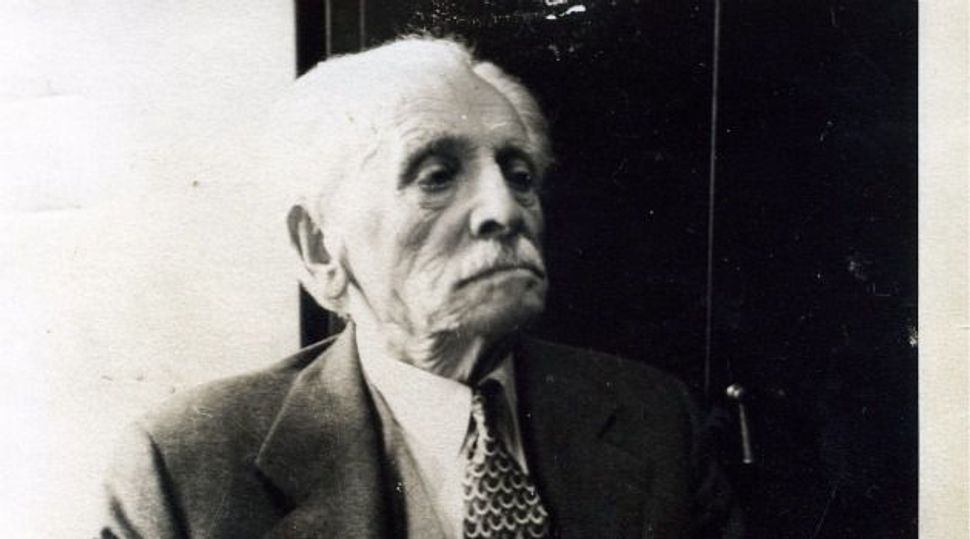

In her elegant essay on Abraham Cahan, Ruth R. Wisse writes that “[a]s editor of the world’s largest-circulation Jewish newspaper, his was almost certainly the most influential Jewish voice in America of the interwar years [1919–1939]; it mattered enormously that he came to choose Zionism over Communism and American democracy over Soviet dictatorship.”

Cahan’s opposition to Communism and Soviet dictatorship is illustrated by a speech he gave in 1940, and his views on American democracy and Zionism are reflected in an exchange of letters with Vladimir Jabotinsky that year. It’s worth looking closely at both the speech and the correspondence.

On May 5, 1940, the Workmen’s Circle—the mutual-aid society founded in 1900 by Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe—held a rally at Madison Square Garden to celebrate its 40th anniversary. The principal speaker was Fiorello La Guardia, then in his eighth year as the mayor of New York, followed by Abraham Cahan.

The rally attracted an overflow crowd that—in the words of the report on page six of the New York Times the next day—was “one of the largest crowds ever to jam its way into the Garden.” “Every one of the Garden’s 19,000 seats was filled,” the Times wrote, “long before the scheduled starting hour of 2 pm.” Police estimated that 24,000 people had crowded inside and that another 15,000 had been turned away outside.

When he arrived, Mayor La Guardia received a standing ovation, lasting more than a minute. He began by praising the Workmen’s Circle for establishing health insurance and care for the chronically ill that predated by more than a quarter-century the programs of the Roosevelt administration. What caused the Times to report the event so prominently, however, was undoubtedly the part of La Guardia’s speech reflected in the article’s title: “KEEP OUT OF WAR, IS MAYOR’S ADVICE.”

The first two paragraphs of the Times article read as follows:

The best role the United States can play in today’s war-crazy world is to keep out of war and by making our own democracy work set such an example for the rest of the world that it will get rid of dictators, Mayor La Guardia yesterday told [the rally]. . . . [T]he mayor declared that this country had the resources, the ability, and the vision to build a democracy in which everyone would have food, shelter, a job, and freedom from the insecurity that he blamed for so much of the world’s ills.

The Times devoted three paragraphs to the reaction to La Guardia’s speech and to Cahan’s remarks that followed:

Although the mayor’s anti-war declaration brought an outburst of applause, there was a no less enthusiastic outburst when Abraham Cahan, editor of the Jewish Daily Forward, and the following speaker, said he did not agree that America’s role should be a passive one.

“A good example is not enough,” he declared. “Hitler must be defeated. Hitlerism is the great curse of the world. And now that Hitler and Stalin are one, both of them must be destroyed.”

Mr. Cahan lapsed then into Yiddish and continued to denounce both Stalin and Hitler. He warned Jews against having any part in efforts to bring Communism to the United States.

In 1940, America was frozen in isolationism, wanting no part of a new European war two decades after the disillusioning American involvement in World War I, which had not fulfilled President Wilson’s claim that it would make the world safe for democracy. Many Jews were wary of adopting any position that differed from the isolationism of their fellow citizens: the American Jewish Committee’s Annual Report that year stated that the war would take a toll on “half our brethren who live in the [affected] countries,” but that the AJC was “convinced . . . of the futility of war” and that “[h]appily, our country is not a party in this conflict.”

It took moral and intellectual courage for Cahan to speak so forthrightly about the need to destroy Hitler and Stalin—and against a merely passive American role in that effort.

A lifelong socialist, Cahan’s eventual endorsement of Zionism came late. The title character in his novel, The Rise of David Levinsky (published in 1917, the same year as the Balfour Declaration), was in many ways—although not all—a stand-in for the author. Near the end of the novel, David describes the girl he wants to marry, Anna Tevkin, as someone whose socialism was “diluted” by nationalism, and he proposes to her even though “she was a nationalist and not an unqualified socialist.” David notes the differences between himself and her father in a two-sentence paragraph: “Tevkin’s religion was Judaism, Zionism. Mine was Anna.” Although extracting political messages from works of literary fiction is always risky, this passage reflects Cahan’s lack of interest as of 1917 in Jewish religion and nationalism.

But Cahan’s public involvement in Jewish issues in America spanned his entire career. That is, he was never concerned solely with the needs of Jewish workers, but with the needs of the Jewish people as a whole. In 1903, the brutal pogrom in the Russian provincial capital of Kishinev took the lives of scores of Jews and left hundreds more injured and violated. It generated Hayyim Nahman Bialik’s historic poem, “In the City of Slaughter,” and it led to a wave of protests in America. Cahan addressed a public meeting at Cooper Union in New York City along with four other speakers, and he addressed a mass meeting of several thousand people at Kesher Israel Synagogue in Philadelphia. In The Voice of America on Kishineff (1904), the editor, Cyrus Adler included a summary of Cahan’s Philadelphia speech:

He asked that the Jews throughout the world unite in protesting against the outrage which had been committed upon law-abiding and peaceable men, women, and children. He spoke of the great meetings that had been held in New York City . . . and asked that the Jews of Philadelphia unite with those of New York and the rest of the country in asking the government to protest against the iniquity. . . . He alluded to the fact that in such calamities there should be no distinction made between socialist, orthodox, or radical. He, the leader of the socialists, known as the infidel, the heretic, stands now in an orthodox synagogue and preaches from the same pulpit with Rev. Masliansky and Rabbi Levinthal [two prominent Russian-born Orthodox rabbis]. He also recalled the effect of the riots in the early eighties, when young students, who were entirely alienated from their faith, returned to the fold, because of the common sorrow that befell the whole house of Israel.

While at various times Jewish socialists have seen traditional rabbis and Zionists as their opponents, and vice-versa, Cahan’s vision was broader.

Much can be learned about his evolving approach to Zionism from his seminal 1940 exchange of letters with Vladimir Jabotinsky, who was in America seeking support for a Jewish army to join the fight against Hitler. Cahan was skeptical that such an army could be formed, and believed the restoration of democracy and the economic benefits of socialism would solve the Jewish problem in Europe without the mass exodus to Israel that Jabotinsky favored. Jabotinsky responded to Cahan as follows:

Some people believe, of course, that socialism—if introduced after the Allied victory—would solve this problem too. Maybe. I doubt it, but maybe. But in this case Jews should be told that an Allied victory without socialism is no remedy to their plight; and we all know that the Allies have not the slightest intention to allow East Central Europe to become socialist if they will win the war and be the masters of this situation. As things stand and as they loom on the horizons of realism, . . . the only practical remedy remains the exodus.

Cahan and Jabotinsky were debating issues going to the heart of the Jewish future in the 20th century. Their political disagreement about solutions did not negate a deeper consensus about the centrality of Jewish identity to their times, and each recognized that international threats demanded more than a passive response from America. Cahan eventually supported Zionism and viewed the establishment of Israel as one of the most significant events in Jewish history.

Wisse ends her essay by suggesting that intellectuals today, both Jewish and non-Jewish, can learn from Cahan’s model of intellectualism and Jewish sense of historical experience. Nearly a century after Cahan’s 1940 speech, as a rising Middle Eastern power seeks nuclear weapons to pursue its goal of eliminating both America (the “Great Satan”) and Israel (the “Little Satan”) in favor of a new totalitarian tyranny, the challenges of Zionism and democracy—and the siren song of isolationism—are once again central to public affairs, and Cahan’s example continues to be both important and inspiring. We need it now as much as ever.

More about: American Jewry, Cahan, History & Ideas, Isolationism, Israel & Zionism